In the lead-up to Christie's fall auction, we've highlighted record-breakers and oddities from Phaidon's Going Once, a compendium of 250 legendary, strange, or otherwise remarkable paintings, prints, and objects from Christie's two-and-a-half century history. Before you bid on this week's lots, take a look back at the groundbreaking and remarkable auctions for now-renowned contemporary artists like Jasper Johns, Rachel Whiteread, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, and more, for whom mainstream auction success can signal or inspire widespread acceptance of once controversial methods and movements.

1. THE HOME OF THE BRAVE

Flags I by American artist Jasper Johns is widely regarded to be one of his greatest prints. It depicts two star-spangled banners side by side, reversed and rotated ninety degrees, so that if they were the right way up the stars would be top right rather than top left.

As with so many of his best works, it is Johns’s unorthodox technique that makes Flags I stand out when compared to screen prints by other artists. Andy Warhol had introduced Johns to this process in 1960, but the latter was slow to see how it would suit his work: the flat expanses of color produced in screen prints suited Warhol, but not the intense mark-making that Johns had made into his signature style.

Johns recalled how he made this screen print alongside master printer Hiroshi Kawanishi at Simca Artist Prints Inc., one of the legendary New York print studios of the 1970s. “By adding a rather large number of screens, and having the stencil openings follow the shapes of brushstrokes, I have tried to achieve a different type of complexity,” Johns said at the time. “One in which the eye no longer focuses on the flatness of the colors and the sharpness of the edges. Of course, this may constitute an abuse of the medium, of its true nature.”

The American flag has become the image most associated with Jasper Johns. In a New York art scene dominated by Abstract Expressionism, with its emphasis on ineffable, sublime themes and maximum emotion, to depict something as humdrum as a flag was a radical gesture. Part of a deliberate tactic by Johns to look at things “the mind already knows,” it allowed him to focus on the experimental use of materials. “One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag,” Johns said of his painting Flag (1954–5), now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “The next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.”

In reworking the image time and time again, Johns found that he could rejuvenate it: “With a slight re-emphasis of elements, one finds that one can behave very differently toward [an image], see it in a different way.” He was able to do just that in this print, working from a photograph of his own painting Two Flags (1973), and bringing a genuinely unique energy and intensity to a medium known for cool flatness. It sold for $101,200 in 1995; an impression of Flags I sold at Christie’s for nearly $1.45m in November 2015, showing that the market for Johns’s prints has risen significantly in recent years.

2. INSIDE OUT

As the history of the Young British Artists (YBAs) is refracted through retelling over time, Rachel Whiteread’s role in the emergence of this talented generation has, arguably, become underplayed. Whiteread, in both her work and her public persona, might now seem remote from some of her peers, but—like that of Damien Hirst—her work appeared in the very first of the Young British Artists exhibitions at the Saatchi Gallery in 1992, a show that gave the group its name.

Untitled (Square Sink) was among the works on view, as well as one of Whiteread’s masterpieces, Ghost (1990). Both reflect the poetic power of the sculptures that propelled the artist to huge success in the 1990s. Ghost was a true breakthrough; a cast from a room in a house on London’s Archway Road, much like the one Whiteread grew up in, in which she sought to “mummify the air in a room.” The result was a Minimalist-inspired sculpture and a lyrical paean to the emotion and memory contained in domestic spaces. The air within and around all manner of other quotidian objects and spaces was also “mummified,” from the space under a bed to the inside of a hot-water bottle. Like her works involving baths, Untitled (Square Sink)—a sculpture of the space found underneath a household sink—has an almost funereal, monumental solidity.

Characteristically, this work conjures not just the object but also its wider cultural use. Just as Whiteread’s sculptures of beds inevitably prompt thoughts of birth, sex, and death, so the cast of the sink becomes a font, a testament to water as a symbol of life, as an element in human ritual. It is also a profoundly strange object, confirming the artist’s ability to find the magical in the most humdrum things and places.

The work was one of the top lots in a sale in 1998 of pieces from Charles Saatchi’s collection, sold to benefit students and graduates of four London art schools—Chelsea, Goldsmiths, the Royal College of Art and the Slade. Christie’s auction raised a total of £1.6m ($2.7m; equivalent to £2.6m/$3.6m today), and, in retrospect, was one of several signifiers of a shift in the London art scene. If the exhibition of Saatchi’s collection at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1997, “Sensation,” marked the apex of the YBAs’ notoriety, the sale, which took place a year later, indicated that Saatchi’s interest in them had begun to cool. Other collectors were therefore able to buy early YBA works from Saatchi’s collection retrospectively, allowing him to fund his passion for supporting new artists coming through in the YBAs’ wake.

3. OF FAME AND PHARMACEUTICALS

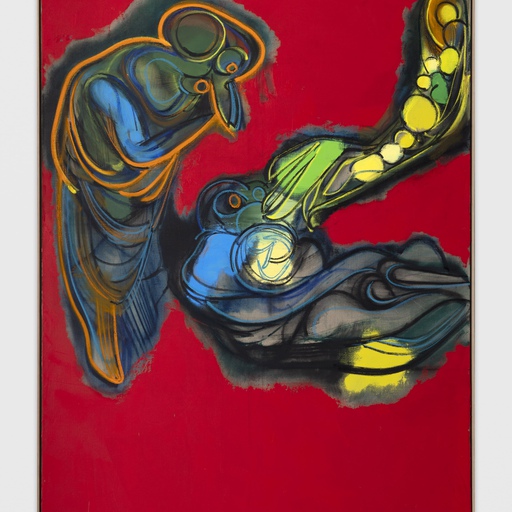

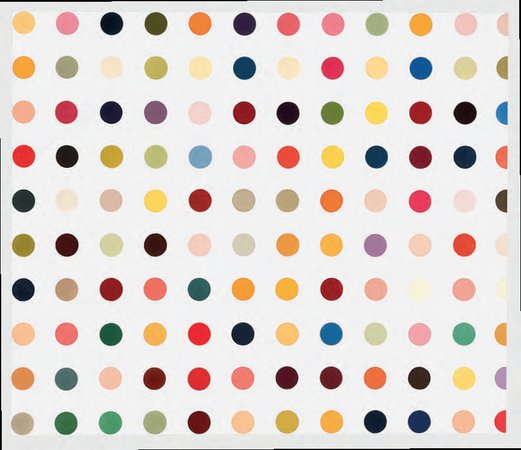

When Damien Hirst’s first spot painting came up for sale in 1996—the first of his works to reach auction—many commentators and journalists wondered out loud if this was the start of a new era. “Art market superbrat makes his auction debut this week,” wrote The Independent. “The appearance of a Hirst at Christie’s is a first swallow indicating greater confidence in the post-recession contemporary art auction market.”

For once the art-world speculation and newspaper hype proved correct. The previous year, buyers had been playing it relatively safe at auction, buying works by Yves Klein and Robert Rauschenberg. The catalogue for the sale in 1996, however, was populated with young newcomers of whom Hirst was the best known. He was already well-known for his formaldehyde-preserved sharks and cows, which addressed the relationship between art, science, and mortality. His ‘Pharmaceutical Paintings’, comprising immaculate grids of colored dots, spoke to the same theme: each titled after individual chemical compounds, their molecular structures sought to distill the dialogue between order and chaos that underpins our existence.

Hard on the heels of this first sale came the “Sensation” exhibition of 120 works from the collection of Charles Saatchi at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1997. Then, in 1998, an auction was held of works from that same collection—many of them by the YBAs or “Young British Artists”: Rachel Whiteread, Jenny Saville, Dinos and Jake Chapman, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Chris Ofili.

With all this very visible activity, prices for contemporary art began to rocket. In 1996, Hirst’s dealer Jay Jopling had declared that he would be happy to see that first-time-on-the-block spot painting make £10,000. Two years later, Acetic Anhydride sold for £122,500. A decade after that, Hirst felt able to ask a cool £50m ($100m) for a single work—a platinum skull encrusted with over 8,000 diamonds called For the Love of God (2007). It was a grand gesture, as if the price tag were as much a part of the work of art as the object.

4. TAKING OFF THE MASK

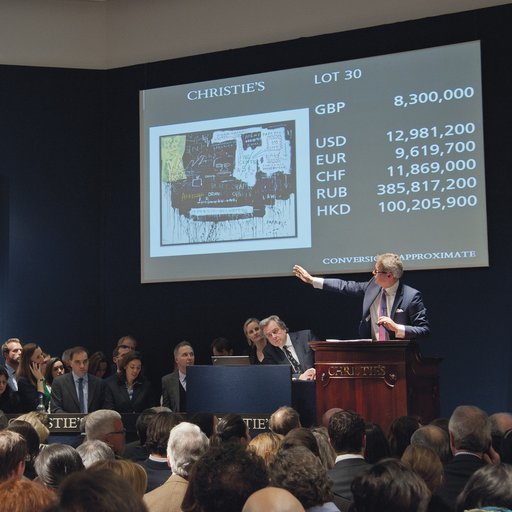

In 1993, at the age of twenty-nine, the artist Zeng Fanzhi travelled from Wuhan, the city of his birth, to Beijing. The Chinese capital was experiencing the early stages of its transition to capitalism and the creation of a new social world. Zeng’s response was to begin his “Mask” series, of which Mask Series 1996 No. 6, a vast diptych, is perhaps the most striking of all.

Mask Series 1996 No. 6 features a line of eight figures informally posed as if for a snapshot on a happy occasion. However, while there are smiles on their faces and the background is painted in a breezy yellow, the picture is profoundly disturbing. The masks symbolize personal and political concealment, representing the idea that honest emotions and true character are hidden during social interaction, as well as being oppressed by the state. The neckerchiefs worn by the figures represent membership of the Communist Party, a sign of collective loyalty, although the masks make it impossible to judge the sincerity of this symbol. Despite having strings to fix them to the figures’ heads, the masks seem to be part of the group’s faces, indicating the permanence of the concealment. The use of a photograph as source material for this painting is also significant; Zeng has spoken of the “simulated posture” we all adopt when being captured on camera.

Zeng draws on both Chinese traditional painting and Western art movements in his work, and Mask Series 1996 No. 6 is a synthesis of the techniques learned in his homeland and the expressionist and existentialist art he saw from the West in reproduction. Francis Bacon’s flayed skin and the broad brushwork of German Expressionism, for example, are evoked in his painterly language.

Christie’s has sold Chinese art for more than 200 years, but the first decade of the twenty-first century has seen interest reach new heights, with numerous records set for works in multiple disciplines and from various epochs. At the time, the highest total for any series of sales in Asia—HK$2.1b (£1.4m/$2.7m)—was achieved in 2007 when Christie’s celebrated twenty-one years of auctions in Hong Kong.

The stage was therefore set for contemporary art to make a splash, and the inaugural evening sale for twentieth-century and contemporary Asian art took place in May 2008, helping to establish Hong Kong as a global centre in the art world. That night, Zeng Fanzhi’s painting set a world auction record for the artist and for Chinese contemporary art. The series, which remains his most highly regarded body of work to date, is seen as a key moment in the development of new art in China.

5. THREE TONS OF TULIPS

Jeff Koons, Tulips, 1994 – 2004. Sold on November 14, 2012 for $33,682,500.

Jeff Koons, Tulips, 1994 – 2004. Sold on November 14, 2012 for $33,682,500.

In 2012, Jeff Koons hit the headlines with the sale of his sculpture Tulips, which set a world auction record for the artist at that time. The sculptural installation—created in five versions between 1995 and 2004, and comprising of seven stainless-steel blooms coated in bright colors—is part of Koons’s “Celebration” series and was consigned by Norddeutsche Landesbank.

The series evolved from Koons’s desire to represent a child’s ecstatic enjoyment of the world. His forms recall Constantin Brancusi’s streamlined sculptures as well as children’s toys. Koons has explained that, “[The ‘Celebration’ series] is about a calendar year and how we perceive different things within the course of a year. You can look at [...] the Tulips sculpture and maybe it will make you think of spring. You can look at Hanging Heart and think of Valentine’s Day, or Cracked Egg and you think of Easter. If you look at Party Hat, you might think of a birthday. There are different forms of celebration within a cycle of time.” Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994–2013), from the same series, was sold for $58,405,000 (£36,270,000) in November 2013, and remains the highest price paid at auction for a living artist. It is now situated at the Wynn casino in Las Vegas.

Tulips looks shiny and weightless, but in reality it weighs more than three tons. “I started to work with polished steel in 1986,” Koons has said. “Polishing the metal lends it a desirous surface, but one that also gives affirmation to the viewer. It’s about telling him, ‘You exist!’ When you move, it moves.” The work was originally installed outside the Norddeutsche Landesbank in Hanover, Germany, over a reflective surface that enhanced the sculpture’s flawless sheen. When it came to Christie’s New York, this presentation was emulated by displaying Tulips on a purpose-built water-filled plinth located in the Rockefeller Plaza, where it became a much-admired temporary feature.

[related-works-module]

6. A BIG BANG

In his gunpowder drawings and outdoor explosion events, the Chinese multimedia artist Cai Guo-Qiang aims to “investigate both the destructive and the constructive nature of gunpowder, and to look at how destruction can create something as well.” Born in southeast China, Cai grew up during the tumultuous years of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). In the 1980s, when he started to become aware of Western contemporary art, he found the cultural climate in China to be too repressive and moved to Japan in search of better opportunities. He began to work with gunpowder in China, then expanded this use in his drawings in Japan and also experimented with explosives on a massive scale. Cai now lives in New York, and works and exhibits internationally.

To create his gunpowder drawings, Cai first sketches a design on sheets of specially made paper placed on the floor. He then scatters gunpowder on top and arranges fuses to form silhouetted designs on the paper’s surface. Pieces of cardboard are laid here and there to disperse the patterns that result from the explosion, and bricks are used to weigh everything down and intensify the blast. When the process is complete, Cai ignites the leading fuse with a stick of burning incense. With a series of flashes and loud bangs, the gunpowder rips across the paper, following the line of fuses. When the clouds of smoke disperse, and stray embers have been stamped out, the drawing is hung up for inspection.

This procedure, which Cai calls an “open production,” took place on 25 September 2013 at the Union Church in Shanghai, during the creation of Homeland. This vast drawing, which is more than 22 feet long, depicts Cai’s home town, the ancient city of Quanzhou, with its pagodas, banyan trees, and distant mountains seen against the ghostly outline of Frank Gehry’s design for the as yet unbuilt Quanzhou Museum of Contemporary Art (an ambitious project that Cai is overseeing).

Homeland was commissioned to celebrate Christie’s first auction in mainland China, which was held the next day. Witnessing the creation of the drawing was an audience of invited guests, many of whom recorded the explosions on their mobile phones. The event, which took Cai, his team, and eight student volunteers three hours to prepare, lasted seven seconds and burned through 66 lb of gunpowder. The excitement continued at the auction itself, with over 200 international clients logged in to Christie’s live to watch proceedings online. The sale achieved RMB154m (£15.7m/$25.1m).

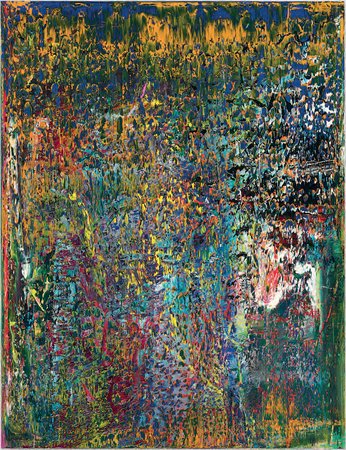

7. THE TENSION BETWEEN CHANCE AND CONTROL

“When I paint an abstract picture,” Gerhard Richter has said, “I neither know in advance what it is meant to look like, nor, during the painting process, what I am aiming at and what to do about getting there. Painting is consequently an almost blind, desperate effort, like that of a person abandoned, helpless, in totally incomprehensible surroundings.”

Abstraktes Bild is one of a large number of paintings that emerged from what is surely the German painter’s most prolific period of making abstract works, between 1988 and 1992. Richter’s process is well known: he applies layer after layer of color, often wet into wet, using a squeegee to pull the paint across the surface in various directions. This is where he ventures into the unknown: he can predict the kind of mark he can create, but cannot be certain what forms and effects will emerge from each of the individual movements with the squeegee. He describes this as a form of chance “that is always planned, but also always surprising.” With typical mischievous modesty, Richter adds that he is “often astonished to find how much better chance is than I am.”

The tension between chance and control has been at the center of Richter’s work since he began to establish himself as a leading artist in the early 1960s. His memorable show at Tate Modern in London in 2011, which subsequently toured to Berlin and Paris, emphasized this push and pull in his work, so that rooms full of abstracts would be punctuated by paintings based on photographs. Everything was ultimately a form of abstraction, even the most representational images.

Richter’s abstracts inevitably inspire interpretations that stray into the figurative world, from molten lava to the Northern Lights and wooded landscapes. The artist has made it clear that he does not set out to depict anything, but neither does he discourage such readings, saying that the paintings show “scenarios, surroundings, and landscapes that don’t exist, but they create the impression that they could exist.” It is this quality that makes them so beguiling and so enveloping, and by far the most popular of his paintings at auction: only one of his top ten highest prices was for a figurative painting.

Abstraktes Bild was sold for nearly £20m in 2014. In that same year Christie’s staged a private selling exhibition featuring Richter alongside his compatriot and former collaborator Sigmar Polke (1941–2010), their first joint show in almost fifty years.

8. THE BED OF LIFE

Tracey Emin had shown My Bed twice before it made its European debut in the Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Gallery, London, in 1999. It was first exhibited in Tokyo and then in New York, although Japanese customs had attempted to destroy it, not believing it was an artwork. Emin later revealed it was her slippers that the Japanese public found to be particularly risqué. But as soon as the Turner Prize show opened, the story of My Bed exploded in the press. Possibly only the furore around Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), his iconic shark in formaldehyde, rivaled the reception for My Bed. They were the two provocative artworks that bookended a decade in which the Young British Artists (YBAs) transformed contemporary art.

My Bed made for a striking entrance to that Turner Prize show in 1999: there it was, in the first room, a ruffled and stained unmade bed, surrounded by detritus that included condoms, a tampon, a vodka bottle, and cigarette ends. It was a memorial to four days during which Emin had stayed in bed, heartbroken at the end of a relationship. She talked of contemplating death while lying there, but says that she chose life, and went to get a drink of water. Initially disgusted by the bed, she returned to it and found it strangely beautiful. It was then that she conceived the idea of transporting it in its entirety to the art gallery. Utterly emblematic of its maker, it is a deeply personal, starkly confessional, expressionist subject married to a tough, post-Duchampian approach to the art object.

My Bed, in becoming a genuine icon, has often been misunderstood and caricatured, with its very real evocation of depression being missed. It was first shown with a noose, which was removed only when it was exhibited at the Tate, and few commentators mention the suitcases bound together with a chain that sit alongside the work: one was the suitcase Emin carried when she left Margate as a teenager; the other a new one she bought when she decided to change her life after the bed episode. Binding them together symbolized the transition Emin made from the past into a new, “internationalist” future, as she called it.

After the Turner Prize show, My Bed was bought by Charles Saatchi. In 2014, he put the work up for auction to benefit the Saatchi Gallery Foundation, and it reached £2.5m, which remains the auction record for a work by Emin. The work was acquired by the Duerckheim Collection and is now on long-term loan to Tate, seventeen years after its first appearance.

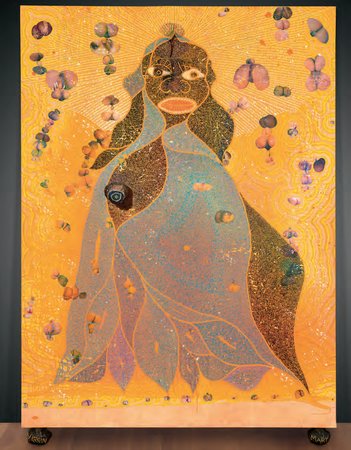

9. AN UNHOLY ROW

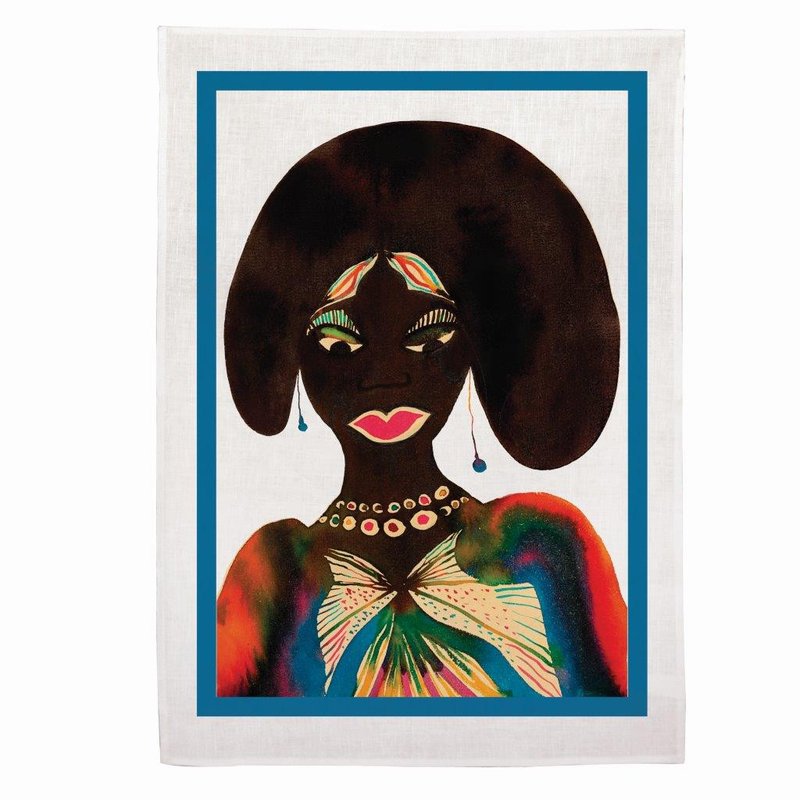

Few works of art have been more misunderstood than The Holy Virgin Mary by the British artist Chris Ofili. The painting was included in “Sensation” (1997) at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the exhibition that featured work by Young British Artists from Charles Saatchi’s collection. When the show toured to the Brooklyn Museum in New York, Ofili’s painting prompted a fierce debate that led Rudy Giuliani, then mayor of New York, to threaten to withdraw the museum’s subsidy and even evict it if the museum did not cancel the entire exhibition (the museum won the lawsuit that followed).

“The idea of having so-called works of art in which people are throwing elephant dung at a picture of the Virgin Mary is sick,” Giuliani exclaimed. Nothing in that statement is accurate, but it set the tone for the debate: reports in leading newspapers claimed the painting was stained, covered, smeared or splattered with excrement. In fact, the dung balls, one of the trademarks of Chris Ofili’s early style, had been used sparingly: to prop up the canvas (the words “Virgin” and “Mary” are written on the balls using map pins) and, on the canvas itself, as the Virgin’s right breast.

Ofili’s use of dung was inspired by a trip to Zimbabwe in 1992, as were some of the decorative patterns in his work, which related to cave paintings he saw in that country. Indeed, across twenty-five years of painting Ofili has consistently explored African identity, meaning that his work can be seen in multiple contexts, including the history of British art and that of the African diaspora. For him, the dung has a multitude of meanings, among them fertility, hence its use for the Virgin’s breast.

Some writers have speculated that the real problem for those offended by Ofili’s painting was that in it Mary is a black woman. Ofili, who was brought up a Catholic, said: “As an altar boy I was confused by the idea of a holy Virgin Mary giving birth to a young boy. Now when I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are.” His was a “hip-hop version,” he said, that explored “the way black females are talked about in contemporary gangsta rap.” Hence the presence of buttocks cut from porn magazines, equivalents to the putti in Renaissance depictions of the Virgin. “I wanted to juxtapose the profanity of the porn clips with something that’s considered quite sacred,” Ofili said.

With these multiple layers—contemporary black pop culture, historical African influences, and witty and knowing takes on art history—it’s no wonder that Ofili was resistant to commenting on the furore. “The people who are attacking this painting are attacking their own interpretation, not mine,” he said at the time. He later expressed regret at its notoriety because it is, he said, “a very beautiful painting to look at.”

This combination of notoriety and visual seduction have made the painting one of Ofili’s best-known works. It formerly belonged to Charles Saatchi and was later purchased by David Walsh, the Australian collector and founder of the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart, Tasmania. When the museum sold the work with Christie’s in 2015, it established a record price for Ofili’s work at auction, selling for nearly £2.9m.

10. MOTHER SPIDER

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1997. Sold on November 10, 2015 for $28,165,000.

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1997. Sold on November 10, 2015 for $28,165,000.

Standing more than 10 feet tall, Spider, Louise Bourgeois’s mammoth bronze arachnid, cannot help but conjure the fear stoked by cult American science-fiction films of the late 1950s. However Bourgeois always intended her spiders to have a more ambiguous role, acting as the embodiment of her own turbulent autobiography. They symbolize the artist’s mother; indeed, a different version, in which ceramic eggs sit in a pouch beneath the spider’s body, is called Maman (1999). “My best friend was my mother and she was [as] deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and useful as a spider,” Bourgeois recalled. The French-American artist’s formative years remained a constant source of inspiration throughout her seven-decade career. “My childhood has never lost its magic,” she explained. “It has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama. All my work of the last fifty years, all my subjects, have found their inspiration in my childhood.” The fact that her mother repaired textiles for a living was significant; Bourgeois identified the spider as a healing creature as much as an aggressor or a symbol of fear.

Bourgeois made her first drawings of a spider in the 1940s, having spent time in the orbit of such exiled Surrealists as André Breton and Joan Miró in New York during the Second World War. She was the link between Surrealism and movements such as Post-Minimalism that appeared in the 1960s, a period when she began to gain long-deserved attention. By straddling the two movements, Bourgeois developed an entirely unique language that made her one of the most influential artists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Her work earned great acclaim from the 1980s until her death.

Although Spider was made in 1997, it was only after the showing of one of the Maman sculptures in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London in 2000 that it came to be regarded as one of her greatest works. While Bourgeois spoke about its relationship to her mother, its gothic, threatening and yet simultaneously nurturing presence also reflected her own personality which, she said, went “from one extreme to the other.” Thus, Spider has come to be regarded as an emblem for Bourgeois and her work. In November 2015, it broke the auction record for a sculpture by a woman artist (almost tripling her own previous record) when it sold for more than $28m.

[related-works-module]