More than a few learned commentators assert that humanity is defined by our natural instinct to make art, an instinct that archeologists and art historians have dated all the way back to 30,000 BC in the darkest caves of the far corners of the world. With humanity's mark in prehistoric cave paintings, rock etchings, and carved objects, we're able to glimpse into the lives of these early people—understanding how they see animals, the human figure, and the strange universe around them. From Phaidon's comprehensive compendiums 30,000 Years of Art and Body of Art, we dug up our ten favorite works of cave art that will rock your world. (And don't forget to consult Phaidon's Cave Art for even more Stone Age fun!)

LION MAN OF HOHLENSTEIN-STADEL

Germany

c.33,000 – 26,000 BC

Perhaps the oldest sculpture in existence, the Lion Man was carved some 30 – 40,000 years ago by someone with an intimate understanding of the structure of mammoth tusk, a close familiarity with lions (which were native to Europe until the second millennium BC), and a mind sophisticated enough to imagine something that did not exist in reality. The sculpture illustrates, perhaps, the fluidity of Ice Age understanding, an ability to accept the morphing of one creature or bodily form into another, unrestricted by the rigidity of modern scientific comprehension. Around 200 fragments of the shattered statue were discovered in a cave in Hohlenstein-Stadel in 1939, on the last day of excavation before the start of the Second World War. The figure was not reconstructed until 1969, and in 2009 further excavation in the cave identified the original find spot and resulted in the recovery of another hundred or so fragments. The now almost complete sculpture was restored again in 2012 – 13. The animal elements are the head and the forearms, which resemble the hind legs of a lion, whereas the legs, feet, and upright stance are human. The horizontal lines etched into the upper arms may represent scarification, tattooing, or body painting.

HALL OF THE BULLS

France

c. 17,000 BC

The cave system of Lascaux, in southwest France, contains almost 2,000 engraved and painted images from the late Solutrean or early Magdalenian period (c.17,000 – 14,000 BC) in seven decorated chambers. One of these, the Hall of the Bulls, is a large rotunda about 17 meters (56 ft) in length, ornamented with 130 figurative and geometric images. Its celebrated polychrome paintings begin at head height and circle around in an organized fashion towards the ceiling. Although the animals depicted are mostly horses, the chamber takes its name from four very large male aurochs (extinct wild cattle, shown here on the left), between 3.5 and 5.5 meters (c.11–18 ft) in length, painted in black outline and facing each other asymmetrically. Numerous geometric signs composed of dots and lines are painted around these creatures, in addition to six small horses accompanied by smaller deer.

The “unicorn,” a seemingly imaginary animal, part bovid (cow or sheep) and part cervid (deer), with an undulating feline outline 2.3 meters (7½ ft) in length, was created by spraying ochre and manganese pigments on the rock wall (for the body), while its straight horns were painted with a brush. Three red bovids appear atop the male aurochs, and one small bear has been painted above another. As an example of organization, technical skill, and natural observation, the site of Lascaux remains unique in Palaeolithic cave art.

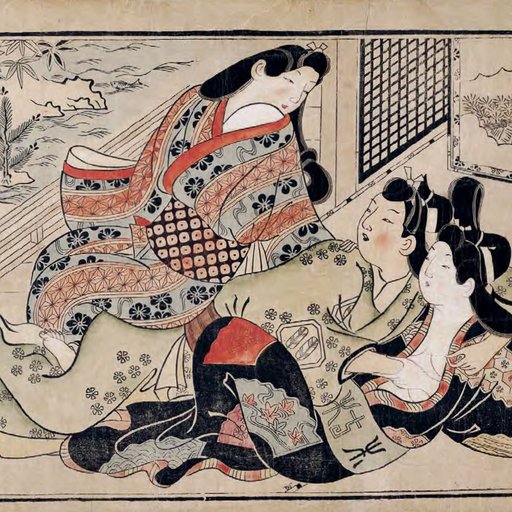

SASH PAINTING

Australia

c. 17000 BC

In 1891 the settler Joseph Bradshaw discovered a group of delicately painted human figures in the Kimberley area of northwest Australia, which were to become known as the Bradshaws. These paintings, some tens of thousands of which exist, are similar in style to so-called “dynamic” figures from neighboring Arnhem Land, and although the Bradshaw figures are difficult to date, comparison with the Arnhem Land paintings suggests they were made before c.8000 BC. An ancient wasps’ nest overlying one painting was scientifically dated to c.17,000 BC, which may indicate a minimum age for the painting.

Bradshaws are elegantly painted human figures who wear a panoply of ceremonial gear, including sashes (as in this example, worn at the waist), headdresses, whisks, skirts, armlets, and tassels—objects that are still worn today in Irian Jaya and which suggest a long tradition of ritual clothing and art in the region. Modern Australian aborigines do not know the meaning of the figures, believing they were painted by a bird that applied its own blood to the rock with its beak. Interestingly, the characteristic fine strokes—some as narrow as 1 millimeter—indicate that the most probable implement used to create these paintings was a feather quill. Technically, Bradshaws are exceptional examples of fine painting, in which specific brushstrokes and holding techniques, deliberate use of pressure, and variable directions of stroke have been observed.

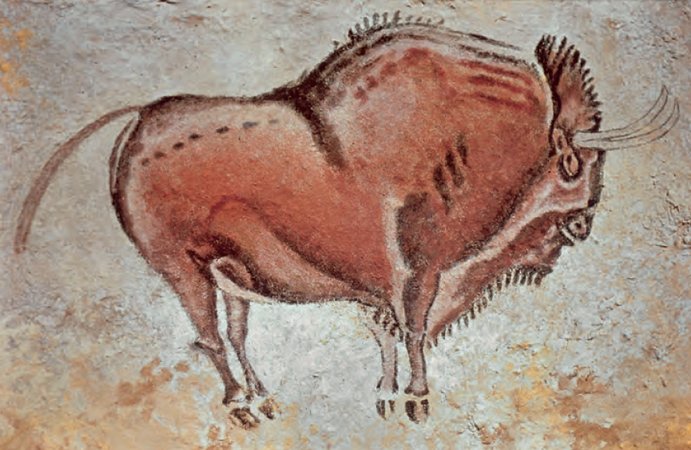

ALTAMIRA BISON

Spain

c. 15000 BC

This detailed depiction of a bison is part of a ceiling painting found in the deep cave of Altamira, on the north coast of Spain. The so-called polychrome chamber contains enigmatic signs and over 30 large paintings of animals, many of them incomplete. The creatures depicted are predominantly bison, although deer also occur, along with black marks that represent eyes on mask-like natural projections on the cave wall. The posture of each animal is imaginatively varied in order to suit the form of the polychrome ceiling, which has a number of natural bosses on to which bison have been “fitted” in a posture of sleep or turning to lick their flanks, the latter a common theme of Upper Palaeolithic art (c.40,000 – 9000 BC).

The paintings have been executed brilliantly in red and black pigment made from manganese dioxide and ochre, which was applied by painting in the direction in which an animal would be stroked.

Analysis of style and pigment suggests that the ceiling is the work of one artist—a Palaeolithic Sistine Chapel created during the Middle Magdalenian period, around 15,000 BC. (The Magdalenian culture was present from Portugal to Poland, c.17,000–9000 BC.) The bison shown here illustrates the artist’s concern with the realistic depiction of three-dimensional perspective; details of pelage, face, hair, and hoofs are characteristic of the period.

HAND STENCILS

Argentina

c.11,000 – 7,500 BC

Between around 13,000 and 9,500 years ago, in a cave located in present-day Río Pinturas, in the province of Santa Cruz, Argentina, hunter-gathers pressed one hand to the rough rock and blew paint against the uneven walls through bone pipes held to their mouths. The result was a highly expressive and busy assemblage of silhouettes in what is now referred to as the Cuevas de las Manos (“Cave of Hands”). Using natural pigments such as iron oxide for earthy red, kaolin for white, manganese oxide for black and, occasionally, jarosite for yellow, this ghostly crowd of left and right hands attests to the vibrant artistic life of some of the earliest human societies in the Americas. Integrated among the hands are later paintings of hunting scenes (or strategies), animals, and zoomorphic figures, suggesting an ongoing collaborative mural or gallery. While handprints and outlines are common to Upper Palaeolithic art across France, Spain, Australia, and throughout the Americas, a vivid evocation of millennia-old artists, the sheer volume, and density of the hands in this cave evoke a unique intensity and urgency of expression.

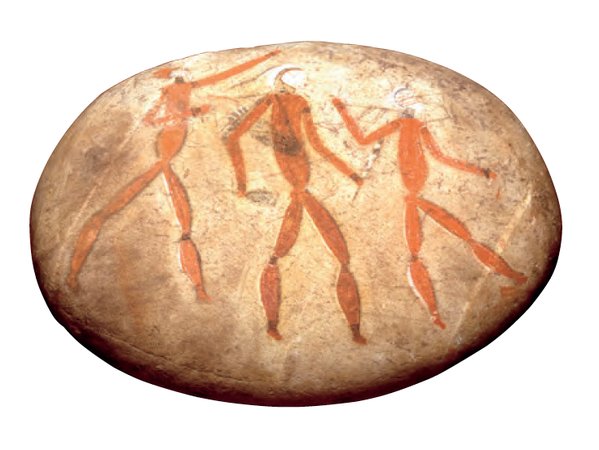

COLDSTREAM BURIAL STONE

South Africa

c. 6000 BC

The three figures on this painted cobble are executed in black, white, and red pigments. The work is similar to other examples of San rock art painted by southern African hunter-gatherers for thousands of years to as late as the nineteenth century, which obey specific stylistic conventions.

The back and top of the head is painted in red, the face in white. The red bodies have an elongated torso and lower limbs, while joints are pinched and the overall effect of the limbs is insect-like. The painted horizontal lines on the face of the figure on the right may indicate that he is a medicine man, as this convention is known at other sites for which a San interpretation is available.

The central figure carries what may be a quill and palette for producing art, making this image possibly the first depiction of an artist in human art.

The stone was found in 1911 above a Late Stone Age (c.40,000 – 6000 BC) burial in the Coldstream Cave, in southern South Africa. Standards of excavation were poor at the time, and existing records are not sufficient to ascertain whether the stone dates to the time of burial (in which case it would be of Late Stone Age date) or whether its association is fortuitous (in which case it could be much later); it probably dates to earlier than c.2000 BC, whatever the circumstances of its deposition.

DABOUS GIRAFFES

Niger

c. 4000 BC

The Dabous giraffes, located north of Agadez in Niger, are some of the most striking examples of Saharan rock art known. It is not known who carved the figures, but they may have been created by the Tuareg people. Rock engravings spanning several thousands of years are common in the Dabous area; over 300 are known, varying in size from quite small to the life-sized depictions shown here. Probably dating to c.5000 – 3000 BC, each giraffe is engraved into a gently sloping rock face, the choice of location possibly a deliberate attempt to capture the slanting rays of the sun so that the shallow engravings were visible at certain times of the day; human figures representing local hunter-gatherers are drawn to scale below the giraffes. The naturalism, perspective, and attention to detail are striking.

Africa’s climate was much wetter during the period in which the engravings were made than it is at present, and the Saharan region was verdant grassland that supported a rich wildlife. Other examples of broadly contemporary rock art in the region depict elephants, gazelles, zebu cattle, crocodiles, and other large animals of the grasslands, although giraffes appear to have been especially important to regional hunter-gatherer groups.

BEAUTIFUL LADIES

Chad

c. 3000 BC

This series of colossal figures, from Niola Doa on the Ennedi Plateau in northeast Chad, is among the most exceptional of those produced some five or six thousand years ago. The contours of the so-called Niola Doa (Beautiful Ladies) suggest voluptuous female curves, while the dense abstract designs may depict body painting.

Images inscribed on rock surfaces in the Sahara chronicle the radical changes wrought by climatic shifts that have historically transformed the region: over hundreds of millennia, the Sahara’s landscape has swung from verdant pasture to extreme aridity. Enormous naturalistic petroglyphs carved between 12,000 and 8000 years ago attest to the astonishing range of animal life that populated the region during that period, including elephant, rhinoceros, buffalo, giraffe, antelope, hippopotamus, lion, and crocodile. A further significant shift occurred around 7500 years ago, when the imagery of regional engravings begins to emphasize human subject matter. This suggests a fundamental change in attitude, whereby man came to conceive of himself apart from nature.

Not long after the figures shown here were created, a series of droughts forced local populations to migrate north, east, and south. Consequently these early designs may be precursors of forms of expression that subsequently developed across the continent.

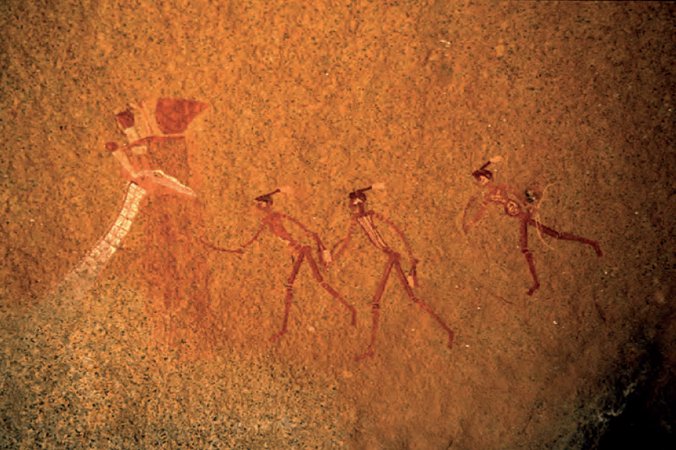

GIRAFFE AND THREE MALE FIGURES

Namibia

c. 2000 BC

This depiction of an encounter between three lithe human figures and a giraffe is painted on a long, narrow shelter high in the great granite massif of the Brandberg, which rises 2500 meters (8200 ft) above the dry steppe-lands of the interior and stands as a barrier between those lands and the coastal Namib desert. The towering mountain appears to have been a sacred place to the San people, judging from the abundance of about a thousand painted shelters in its valleys and upper ridges.

Most of the wealth of engraved and painted images that have survived across Namibia’s arid landscape were created by nomadic hunter-gatherers over the last 6000 years, and many of these are found concentrated within caves situated in the Brandberg. The scene has been interpreted as an invocation for rain, given that the giraffe’s neck appears to be extended through clouds and drenched by a downpour of red precipitation. Like other polychrome San paintings, this one is articulated with crisp outlines and finely modulated brushstrokes, the main medium being pigments of finely ground iron oxides, animal fat, or blood. Blacks were obtained from charcoal or manganese, whites from calcite or clay; a range of other colors extends from deep purples and reds to yellow-ochre shades.

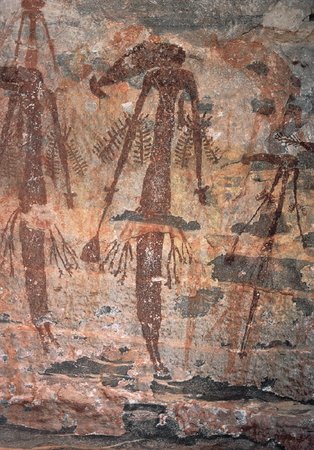

THREE HUMAN FIGURES

Tanzania

c. 2000 BC

These three attenuated and willowy figures enhance a large hillside shelter in central Tanzania. It has been suggested that the distinctive configuration of their prominent heads may represent elaborate hairstyles or headdresses. This painted passage is striking for the extreme delicacy of the wispy, ethereal forms. So organic is their appearance that they evoke the imprint of a fossilized fern or finger.

Unlike Europe’s Palaeolithic paintings, which are found deep within caves (e.g. the Hall of the Bulls), painted and engraved images in Africa tend to occur in far more accessible cliff shelters and below shallow overhangs. In eastern Africa almost all of the rock art is found on a massive inland plateau that extends from the Zambezi River valley to Lake Turkana. This corpus consists primarily of paintings concentrated in central Tanzania, which have been attributed to ancestors of the modern Sandawe people. In this region it appears that artists worked predominantly in a single primary color, relying exclusively on red, black, or white values. Paintings whose subject matter is rendered in red tones feature animals, people, and abstract geometric motifs.