The work of Mona Hatoum concerns the intimate bodies of the disenfranchised, controlled and in opposition to the machine of politics. Born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1953, shortly after her parents fled Palestine, Hatoum began making performance and video-based work, probing subjective narratives of displacement and isolation through the lens of gender and identity theory. In the 1980’s her medium matured into feminist, minimalist , conceptual , and object-oriented installation , earning her a coveted spot in the art history books.

Here, we've excerpted this interview between Hatoum and the art critic Michael Archer from Phaidon's monograph Mona Hatoum . Read on to discover the motivations behind the audacious artist's most provocative, visceral works.

The basic facts of your early biography are well-documented. You were born in Beirut and came to this country in 1975. Intending only to stay briefly, you had to remain because the war broke out in Lebanon. There are a couple of things that I’d like to explore to expand that set of very simple facts. First, the way in which you have described ending up going to art school at the Slade. You’ve said that, finding that you had to stay, you thought you may as well go to art school. There must have been some awareness that you wanted to do that before that time.

I have always, ever since I can remember, wanted to be an artist, and I always assumed that once I finished school I would go to university and study art. But my father couldn’t support me through art school; he wanted me to study something that would get me a career and a job right away. I ended up doing a two year graphic design course at the university in Beirut and then worked in an advertising agency for two years, where I was very unhappy. I was taking evening courses in anything available just to keep me going: drawing, ceramics, photography – quite a bit of photography. Eventually I decided to go back to the university for another two years, for a BA. It was at that point that I came to London for a break. All along I had been thinking that I would eventually come to England for a postgraduate course, in part because I had a British passport and thought it would make things easier. When I found myself stranded here I decided that I could do something with my stay and enrolled in the Foundation course at the Byam Shaw School of Art. At the time I thought that I might stay here for a year and then go back, but the war got worse. Anyway, I very soon realized that staying in London and being able to visit the Tate and the National Gallery and seeing all these artworks "in the flesh" would be an education in itself.

In discussing your work, particularly your performance and videos from the early 1980s, you have pointed to the Western European way of relating body to mind and how that contrasted with the attitude in Lebanon, where there is no straightforward split between mind and body .

The first thing I noticed when I came here was how divorced people were from their bodies, although recently the art world has become far more preoccupied with the body. I am convinced that this is a direct result of the AIDS epidemic which has forced everyone to become aware of the body’s vulnerability. Since my early performances, the body has been central to my work. Even before that I was making small works on paper using bodily fluids and body rejects as materials. I have always been dissatisfied with work that just appeals to your intellect and does not actually involve you in a physical way. For me, the embodiment of an artwork is within the physical realm; the body is the axis of our perceptions, so how can art afford not to take that as a starting point? We relate to the world through our senses. You first experience an artwork physically. I like the work to operate on both sensual and intellectual levels. Meanings, connotations, and associations come after the initial physical experience as your imagination, intellect, psyche are fired off by what you’ve seen.

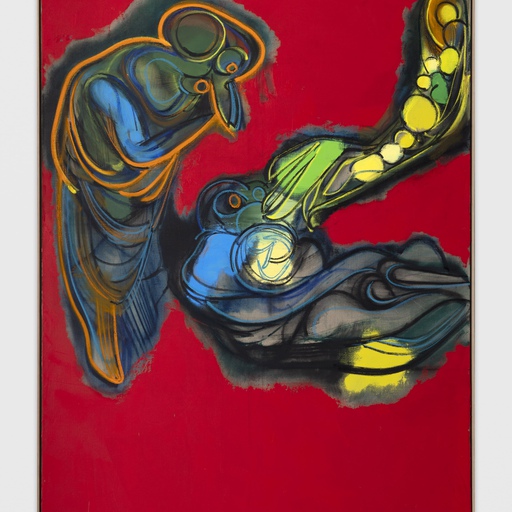

Mona Hatoum's

Birds of a Feather

(1997) is available on Artspace for $1,500

Mona Hatoum's

Birds of a Feather

(1997) is available on Artspace for $1,500

Did you very quickly recognize the relevance of performance to the way you were thinking?

Coming to performance was quite a gradual process which resulted from a number of coincidences. When I was at the Slade, after the Byam Shaw, the experimentation I was doing was quite dangerous. I was using 240 volts of electricity passing through a “circuit” of metal household objects; or an electric current going through water to connect electrodes that intermittently lit up a light bulb. I could not put up these works without getting permission from security and fire officers, and very quickly got tired of all the bureaucracy. As a way out, I would put something up for a very short time—half an hour, an hour—to an invited audience. These works became like a kind of performance or demonstration. This also coincided with my new political awareness at the time. The Slade politicized me. I got involved with feminist groups, I became aware of class issues, I started examining power structures and trying to understand why I felt so “out of place.”

This sense of displacement was something you had to deal with?

I had both to understand it intellectually and integrate it emotionally into my life. It was a time of tremendous personal struggle, turmoil, and confusion. Performance was very attractive to me because I saw it as a revolutionary medium, setting itself apart from the gallery system and the art establishment. It fit exactly the kind of issue-based work I was beginning to make.

Were there examples that you followed: Stuart Brisley , say, who was teaching at the Slade then, or others such as Marina Abramović or the Viennese Actionists?

Of course Stuart Brisley and others, but mostly I was hanging around with a group of students who were involved in performance. In fact my first performance at the Slade was a collaboration with two other students whom I had overheard talking about an idea for a work. They were planning to perform two independent actions in the same space without prior knowledge of what the other would do. I started suggesting other things to them, like somehow intervening in the audience’s space. They invited me to participate with them, and this was when I used a live video camera for the first time, to scan and annoy members of the audience while they were trying to watch the performance.

Your dealing with the body, with the personal both as theoretically enlarged through feminism and in the physical sense you described, is evident in your work right from the beginning, even as far back as the 1981 performance, Look No Body! , which you made while still a student at the Slade.

With Look No Body! I was considering the body in terms of its orifices, and how some of the orifices and the activities associated with them are considered socially acceptable and some are not. I was trying to unite the activity of, say, drinking and pissing. I should have called it United Orifices or something like that; it was quite humorous. I had a video monitor in the space which was connected to a live camera in the toilet. I drank cups of water and offered every other cup to the audience, hoping to incite them to use the toilet. I used it myself two or three times. Throughout the performance you could hear my voice on a soundtrack reading out a detailed scientific account of the act of pissing, or “micturition” to use the scientific term. It was like looking inside the body while keeping the “correct” distance from it. My accent was much more pronounced then, so trying to read all these scientific words made the whole thing quite funny.

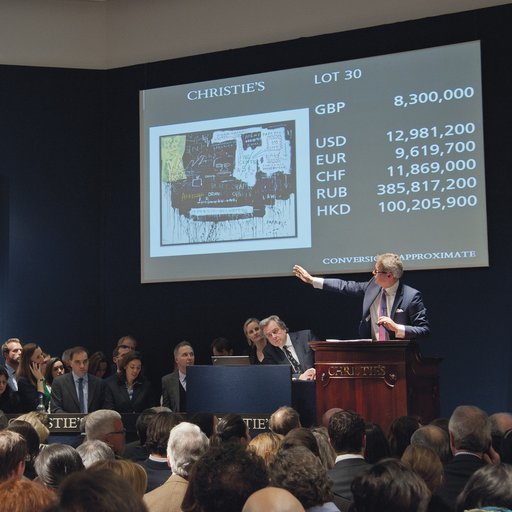

Jesús! Mexico City

(2002) is available on Artspace for $5,000

Jesús! Mexico City

(2002) is available on Artspace for $5,000

That performance also asks fundamental questions about identity. The scientific viewpoint of the soundtrack offers a certain perception of the world; one that conflicts with a very physical understanding of what, where and who one is. This concern with identity is a thread that runs through your work. In Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera! (1980) you trained a video camera on your audience, relaying the image to a monitor which they could see. Out of their sight, however, you had someone mix into the signal other images of unclad body parts, both male and female. It appeared that you were seeing through their clothing and shifting their gender.

Yes, I was doing some gender bending there, but there was also a desire to look behind the surface or beyond social constructs. In these performances, I was also interested in the issue of surveillance and the penetrating gaze. Around the same period I made a proposal for the “New Contemporaries” exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. In those days the toilets were on either side of the bookshop. I wanted to place a small monitor above each door and connect it to a live video camera trained on the cubicle in each of the two toilets. I wanted to look into the taboos around certain bodily functions, and how the body’s orifices have been organized in a hierarchical structure.

Did you find that there was a certain critical resistance to some of the things that you were doing, in so far as they could be construed as objectifying the body in a very negative way? In the end, for instance, your ICA proposal was rejected.

The ICA wouldn’t allow me to put it on although it had been selected by the “New Contemporaries” committee. I was told that the toilets are in a public space, where people have not made a conscious decision to be confronted by art—can you imagine this kind of response now? I then tried to do the same work for my postgraduate show at the Slade, but it was turned down again. So I put up a statement in my space documenting the history of the piece and how it has been censored. Because I was not allowed to use the toilets, I constructed a male and a female toilet in the main studio space, but of course there it became something else. In Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera! , where I focused my live video camera on members of the audience, I was criticized for being aggressive and invasive. I was trying to make people aware of the fact that we are constantly subjected to some mechanism of surveillance – the invasive look. It was making people aware by showing an exaggerated form of surveillance. Of course, I was invading people’s boundaries.

If you do something by example you’re involved in the whole process yourself: you are as gazed upon as anybody else. You are complicit and not in a position of power. Was it, however, seen as manipulative rather than as having to do with shared responsibility?

People got up and walked out of that performance, asking me why I was doing this to them. I remember a review that described one of my works as “another macho performance by Mona Hatoum.” At that time people were talking about the gaze being a male thing and I was insisting that it was not necessarily so. I suppose I was trying to challenge prescribed male/female roles. I have always resisted those stereotypes, and I was criticized, even by feminists at one point. I collaborated with my friend Brenda Martin in a performance which was basically about competition between women. We were both quite critical of this blanket concept of “sisterhood,” and wanted to question whether competition is an inherently male trait. We were accused by women of being publicly critical of feminism.

These issues and preoccupations are still in a lot of what you do. I don’t see a split between your early performance period and a subsequent phase in which you went on to do other things. A sense of the body, the way in which you see relationships of power, questions of gender, considerations of cultural background and placement—those things are persistently there.

Very much so, but now I’m not using a clear narrative. I’m not pointing a finger directly at one issue or another. Things are implied and not directly stated.

How much do you think that was just to do with the times? There was a lot of work like that in the late 1970s and early 1980s; it was the fashion.

Yes, of course. In the 1980s it was possible to make didactic political statements. I think we have gone beyond obvious statements into something perhaps a bit more sophisticated and subtle. Some work of artists I admired in the 1980s—for instance, Barbara Kruger —can look quite dated now. I don’t think art is the best place to be didactic; I don’t think the language of visual art is the most suitable for presenting clear arguments, let alone for trying to convince, convert or teach.

Visual art’s not didactic.

In 1988 I was invited to do an installation for an exhibition called “Nationalisms: Women and the State” in Toronto. It was one of those times I felt I had been given an assignment because I was known as a political artist. At the time the Intifada was happening in the West Bank and Gaza, which was the biggest spontaneous demonstration of social protest or resistance that had ever taken place in that part of the world. The work had to have something to do with women and it had to deal with stone-throwing. That’s what the Intifada was about: kids throwing stones at the army and getting bullets back in return, hundreds of bullets. I made a work with a title which was something like A Thousand Bullets for a Stone. I found a newspaper image of a woman confronting a soldier holding a big gun, and in the background there were these kids throwing stones at the soldier. It was perfect. I projected the image quite large on two walls and had stones scattered all over the floor. Each stone was labelled and numbered, like weapons when they are seized and displayed by the police. At least there was a bit of humor in the work, but overall I felt really unconvinced by it because the Intifada was such a strong expression of dissent or protest, and had manifested itself in so many different ways. I felt almost opportunistic using that material; for me that was really the beginning of the end of working in an overtly political way. When you present someone with a statement in an artwork, once they get it, they either agree with you or dismiss your argument and move on to the next thing—no need to look again. It was the same with black issues.

Even when there was much more of a sense of narrative to what you were doing, you rarely did work that was specifically directed at where you came from. You did the performance Under Siege , which referred to Lebanon, and later you did the video piece Measures of Distance , which was about conversations and correspondence with your mother.

Under Siege happened a week before the Israeli invasion and the siege of Beirut; it was almost like a premonition. But in general in my work at that time, I was trying to remind people that wars were still raging in many parts of the world. I say “still” because at that time most people’s energy was going into the anti-nuclear movement and “keeping the peace.” They were saying, “We’ve had peace for forty years and we want to keep it that way.” But that only concerned Europe. I was trying to remind people of conventional wars happening outside the West. For instance the billboard work Over My Dead Body touched on that, though there was also a humorous reversal of power relationships. Measures of Distance was really the only work where I consciously used autobiography as the text of the work.

You mentioned black issues just now. How useful and how restrictive was it to think about a lot of these issues of cultural difference in terms of blackness? There has been a totalizing use of that word, which can erase all kinds of differences within its scope.

At the beginning it was important to think about the black struggle as a total political struggle. There are common political forces and attitudes that discriminate against people. In the same way that feminism started off with this totalizing concept of “sisterhood,” and then we ended up with many feminisms, if you like. The black struggle became more diversified once the basic issues were established. And blackness here is not to do with the color of your skin but a political stance. In the early 1980s I don’t think I saw my practice as part of the black struggle—I was doing my own thing. I have always worked in an intuitive way and couldn’t see my work as serving any group, political or otherwise. I was basically trying to deal with an environment that I had experienced as hostile and intolerant and eventually those feelings began to pervade the work—and still do. For instance, they are evident in a piece I’ve made for an exhibition at De Appel: a little doormat made of pins with the word “Welcome” in it. It’s related to a series of works I made last year which had to do with carpets. Visually I find it quite beautiful, because the word “Welcome” is made with shorter pins, so it’s like a little recess within the surface of the mat. From a distance you see the word clearly, but when you get close and you look down at it, the word almost disappears.

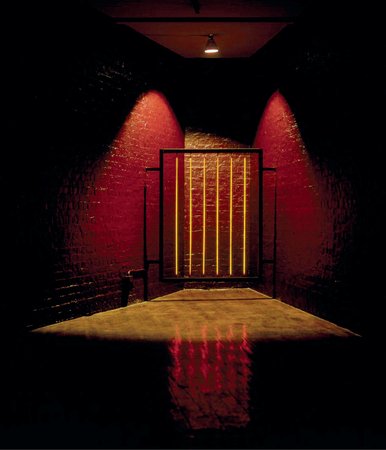

The first work with that dual characteristic of being both welcoming and potentially harmful was The Light at the End , the installation you did at the Showroom in London in 1989. The glow from vertical electric elements at the rear of an otherwise darkened space drew you towards them, until you were hit by the intense heat they gave off and realized the immense danger of the situation. Is it also true that the title—“the light at the end” (of the tunnel) – was important for you? Was there something revelatory about doing that piece?

The Light at the End was the beginning of a whole new way of working. In a sense with this work I was going back to a minimal aesthetic and working with certain material properties which amplify the concept. The associations with imprisonment, torture and pain were suggested by the physical aspect of the work and the phenomenology of the materials used. It was not so much a representation of something else but the real thing in itself. I felt satisfied for the first time that the balance between the issues, the materials and the space was just right for me. It also had this paradoxical aspect of being both attractive and repulsive. It was obscene. The space at the back of the Showroom is this strange funnel shape which made me think of a trompe l’oeil perspective of a tunnel. The expression “the light at the end of the tunnel” came to mind and I used it in the title to set up the expectation of something positive which is then disrupted when you realize that the light was actually red hot electric bars that could burn you to the bone.

The Light at the End

(1999)

The Light at the End

(1999)

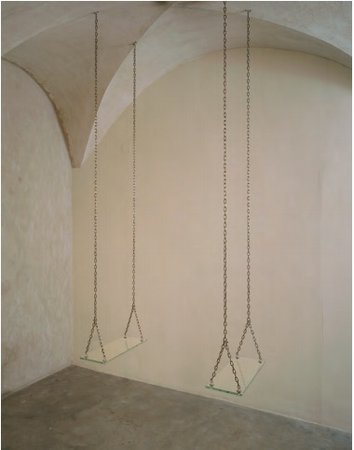

I’m interested that you mention Minimalism, because it also seems to me that your more recent work clearly pulls that back in. I’m thinking, to mention a few, of the very spare white installation at the South London Art Gallery in 1993, with the glass swings hung very close together; or the form of a piece like Socle du Monde (1992–93); or the mats you just mentioned; or the glass bead floor piece.

I like to explore the sensuousness of materials and use them to create an emotional charge, if you like. In A Couple (of swings) I feel that the elegance and coolness of the swings makes the tension of an impending disaster—they could swing towards each other and smash to pieces—even greater. Socle du Monde is a very good example because it was specifically a reference to the archetypal form favored by Minimalism, the cube. But instead of it having a machined, clean surface, untouched by human hands, I wanted to turn this upside down and make it very organic. The strange furry texture on the surface gives you a moment of anxiety because when you first see it you don’t immediately recognize the material.

A Couple (Of Swings)

(1993)

A Couple (Of Swings)

(1993)

The turning upside down, which refers to Piero Manzoni’s gesture in his original 1961 Socle du Monde , is allied to turning inside out. In your Socle, the way in which the iron filings cluster on the cube’s magnetic surface make it look visceral: like intestines, or the brain.

I was commissioned to do that piece for an exhibition in Montreal called “Pour la Suite du Monde.” First I thought, “Here we go again, they want me to make a political statement about the state of the world.” I was resisting doing something very obviously political, but in fact they seemed to have a very open-minded attitude about what constitutes a political statement. They had invited artists like Hans Haacke, Alfredo Jaar and Adrian Piper , but also less political artists like Giuseppe Penone , for example. So I decided to make this piece which referred to the world put on a pedestal, but a pedestal that might have been eroded by some kind of disease and so had lost its stability. At the same time it was an excuse to play with this intriguing and beautiful material. When I made Socle du Monde and saw those meandering shapes that looked like intestines, I decided to make a carpet with the same pattern of “entrails,” which I called Entrails Carpet . I thought it would look quite repulsive and I wanted to contradict that by using a seductive material. While researching another piece a year or so later, I had a lot of rubber samples sent to me. One was this translucent, almost opalescent silicone rubber, and I knew that would do it.

Does it sometimes happen that you light upon material and say simply, “I’d like to work with this stuff?”

Yes. But it is more that I recognize certain properties in a material I come across, that I feel would work for certain ideas I’ve had in the back of my mind for a while. Sometimes it is the space that triggers certain associations, or sometimes the possibility of using certain local materials and crafts inspires the work.

Like those glass beads you used in the installation in Rome?

Oh yes. I was in Rome trying to work out ideas for a piece, and I kept coming across marble everywhere. It made me wonder whether the marbles kids play with were called that because they were originally made of marble. Also, the gallery space at the British School at Rome had a very busy herringbone-patterned floor, which I did not like very much. I started thinking of covering the entire floor with marbles made out of Carrera marble, like a carpet, but that turned out to be very expensive. A few weeks later, I came across these transparent ones which had the additional quality of reflecting the light beautifully. So they looked very seductive but at the same time they created an unstable surface on which you could slip and fall.

You have been collecting your hair for a long time.

A very long time. Sometimes an idea develops over a long period of time before it finds a “home,” so to speak. The hairballs that ended up in Recollection were collected over a period of six years. I made one accidentally when I was staying at a friend’s place in Cardiff in 1989. I had just started my job there. It was the hair that came off my head in the bath. I didn’t want to leave it behind, so I picked it up and was playing with it absentmindedly, rolling it in my hands. It was a perfect ball, very cocoon-like. It was beautiful. I decided to collect them without any specific idea of what I would do with them. I made a hairball every time I washed my hair and they ended up in shoeboxes under my bed. When I saw the space in Kortrijk I felt that this was the time to use the hairballs, partly because the space had been occupied by women. I visualized the hairballs as dust balls that gather in the corners of rooms. Similarly, I had been looking for an excuse to use heat for about three or four years before I made The Light at the End . I had seen the work by Pier Paolo Calzolari which used ice in “The Knot,” a fantastic Arte Povera exhibition at P.S.1 in New York in 1985. I still think that is the most brilliant exhibition I have ever seen. It was a major experience for me. When I saw that work I thought, it would be nice to make a work using heat. I find it difficult to build pieces for no specific reason. You know this little idea for the doormat? I had this idea before I made the big pin carpet or the prayer mat, but I had no specific reason for making it until I saw the space at De Appel. They have a room that looks like a living room with a narrow doorway, and I thought it would look good just inside that doorway. That was the incentive to make it.

Visual welcoming and the contrasting physical danger recur in your work, like in your installation at Mario Flecha Gallery in London in 1992. The wires strung tautly across the space guided the viewer in a very helpful way, yet if you strayed slightly off the path you would cut your ankles, groin or neck. This sense of danger comes up again in the visually provocative baby cot, Incommunicado , where the mattress base is made from cheese-slicer wire.

The Mario Flecha installation was an instance where I felt that the balance between beauty and danger was taken to an extreme. It looked like an effortless drawing space, almost ethereal but also quite lethal. Every aspect of life is full of contradictions: some people think that aesthetics and politics don’t mix, but that’s ridiculous. When I moved into the studio in Cardiff I had this vast space with nothing in it. The first thing I did was to stretch these wires across the space. The Mario Flecha Gallery gave me the perfect opportunity to use this idea two or three years later. I see furniture as being very much about the body. It is usually about giving it support and comfort. I made a series of furniture pieces which are more hostile than comforting. Incommunicado is almost like an imprisoning structure, with its cold metal bars. I replaced the solid platform that would have supported the mattress with taut cheese wires.

There was also a chair, Alive and Well , which used electric elements.

Don’t remind me of that! For a couple of years after I made The Light at the End no one wanted to show anything else. It was made as a site-specific piece for the space at the Showroom and I never, ever thought of it going anywhere else. The curators of “The British Art Show” insisted that I reproduce it for the tour rather than make new work. But then it became something else, because putting it into the museum it had to have all the security devices to make it childproof, foolproof, everything-proof. I was working on elements of Light Sentence and Short Space in my studio in Cardiff, but no one was interested. I made Alive and Well as a sequel to The Light at the End , but I didn’t think it worked. I think it was a bit too obvious.

The piece with the two chairs is intriguing, the big chair with the little chair butted up against it. Why is it untitled?

I didn’t give it a title because I wanted to keep it open. That was actually one of my first furniture pieces. I had made the two very large installation works, Light Sentence and Short Space , for an exhibition at Chapter in Cardiff. I saw the large-scale pieces as referring to some kind of institutional violence. I wanted to place another piece in the space between them which dealt with the same ideas but on a more personal, domestic level. It was referred to as Mother and Child. The two chairs have an unequal but inescapable relationship. They are very angular, cold and cage-like, but at the same time there’s a symbiotic relationship between them because they are so similar.

Light Sentence seems to be a grand refusal of any possibility of fixing a particular meaning, of saying “This is about this.” The whole thing is so utterly mobile: the scale changes, the relationship between the viewer and the elements of the work—the light source and the walls of cages between which one can stand—constantly shifts. The manner in which the shadows of these cages are thrown onto the walls by the slowly moving light bulb makes them both hugely threatening and insubstantial. The work goes through all the things we have talked about so far and beyond.

I’m happy to hear you say this, because most people look for a very specific meaning, mostly wanting to explain it specifically in relation to my background. I find it more exciting when a work reverberates with several meanings and paradoxes and contradictions. Explaining it as meaning this or that inevitably turns it into something fixed rather than something in a state of flux. Years after making this work, I still discover interesting associations, sometimes pointed out to me by viewers.

Following Short Space and Light Sentence at Chapter , and Socle du Monde in Montreal, you did Corps étranger for the Centre Pompidou in Paris. This endoscopic exploration of the body brought forward concerns explored in the performances we talked about at the beginning. Look No Body! included the sound of the heartbeat and the noises of the body; the gaze of Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera! is here sharpened so that it can penetrate not only clothes but also skin and flesh. Was the Pompidou show an opportunity to realize an idea that you actually had had that far back?

Yes, it was exactly that: a piece that I had shelved because nobody would take me seriously. As a student at the Slade, I thought I was entitled to hassle the doctors at the University College Hospital across the road. They wouldn’t do the endoscopy on me, but I managed to get a sound recording of my heartbeat and stomach rumbles, which I used in Look No Body! and eventually in Corps étranger . It only became possible to make this work when the Centre Pompidou commissioned me to produce it. Without their influence and financial support I would never have been able to make a video installation. So Corps étranger was a very old idea, but there are a lot of old ideas that keep coming up in different ways. There are different strands in my work that develop over a long period of time and keep coming in and out of focus. For example, I’ve recently made a piece related to Light Sentence , because that work is “still there” in my mind. Certain works I made as a student were about the dispersal of the body, and this is now coming up in works like Recollection . I used to collect all my nail parings, pubic hair, bits of skin and mix them with pulp and bodily fluids to make paper: a kind of recollecting of the body’s dispersals, if you like. Pubic hair I had collected all these years ago ended up in a much larger work, Jardin Public . There is a triangle of pubic hair that looks like it is growing out of the holes in the seat. Incidentally, this work was the result of discovering that the words “public” and “pubic” come from the same etymological source. Some of my current work represents the maturing of ideas from many years ago, ones that I would not articulate at that time without relating them directly to their sources—a news item, or even a childhood memory—like a kind of illustration.

Tell me about working in Jerusalem.

Going to Jerusalem was a very significant journey for me, because I had never been there. My parents are Palestinian. They come from Haifa, but have never been able to go back since they left in 1948. Jack Persekian, who has this little gallery in East Jerusalem, and I had been discussing the possibility of doing the exhibition there for over two years. I kept postponing it because emotionally it’s a very heavy thing, and I wanted to be able to spend a whole month out there, producing the work.

What work did you do when you were there?

I ended up making about ten works. I made three installations and a number of photographic works and small objects. The ideas I had proposed beforehand seemed to be about turning the gallery into a hostile environment, but the environment outside was so hostile that people hardly needed reminding. On my first day in Jerusalem I came across a map divided into a lot of little areas circled in red, like little islands with no continuity or connection between them. It was the map showing the territorial divisions arrived at under the Oslo Agreement, and it represented the first phase of returning land to the Palestinian authorities. But really it was a map about dividing and controlling the area. At the first sign of trouble Israel practices the policy of “closure;” they close all the passages between the areas so the Arabs are completely isolated and paralyzed. When I first came across it, I had no intention of using it, but a week later I decided that I would like to do something with this local soap made from pure olive oil, and the work came together. Originally I was going to draw the outline of the map by pushing nails into the soap, but it looked quite aggressive and sad. I ended up using little glass beads which I pressed into the soap. The piece is called Present Tense ; it’s about the situation as it was then. Now, with the change in government, some of those areas are not being returned to the Arabs. The Palestinians who came to the gallery recognized the smell and the material immediately. I saw that particular soap as a symbol of resistance. It is one of those traditional Palestinian productions that have carried on despite drastic changes in the area. If you go to one of the factories in Nablus, the city north of Jerusalem which specializes in its production, you feel you have stepped into the last century. Every part of the process is still done by hand, from mixing the solution in a large stone vat, to pouring it on the floor, to cutting and packing it. I also used it because of its transient nature. In fact, one visitor asked, “Did you draw the map on soap because when it dissolves we won’t have any of these stupid borders?” When the exhibition opened and Israeli people came from Tel Aviv, they started reading a reference in the soap to concentration camps. This couldn’t have been further from my thoughts. Those two readings of the work give you an idea of the very different backgrounds and histories of the two cultures trying to coexist. For another piece I brought into the gallery a metal bed which I’d found in the street. I attached casters to the legs and then proceeded to immobilize it by tying it down to the floor with fishing wire. The wires were invisible—you almost tripped on them before you saw them. I called it Lili (stay) put . I was having fun with the titles. One visitor said it felt just like their situation, that everything is trying to push them out but invisible threads tie them down. I was impressed that he’d made the connection between an inanimate object and his situation.

So someone who knows nothing about Conceptualism or Minimalism won’t necessarily see some of the formal resources you are employing. You’ve said similar things about the performance you did in Brixton, where you walked around with Doc Martens boots tied to your feet. There was a directness of perception amongst the passersby which suggested that people knew exactly what was happening.

Yes, because that was another instance where I was performing for an uninitiated audience—passersby—and addressing issues that they experienced in their everyday life: police presence and surveillance. Anyway, the saddest thing in Jerusalem was the policy of “closure” that restricted movement for the Arabs. I gave a piece the title No Way as a response to that. It was a large spoon I’d found full of holes, and I decided to block all of them with nuts and bolts. At the same time it became an uncanny and threatening object, like a weapon. I have since made another version of it.

The colander.

Yes, No Way II . I did another residency this year which was extremely inspiring. I spent a month at a Shaker community in Maine, the last remaining Shaker community. It is a small community of only eight members. There was this wonderful, settled feeling of warm domesticity in the place, so household objects became my focus. I did some rubbings of colanders which the community had made by hand in the 1830s. I had fun knitting and weaving with spaghetti and pasta and making miniature baskets. I like turning up at a place and letting myself be inspired by the situation. After being with the Shakers and making very discrete little objects, I then went to San Francisco for another residency at the Capp Street Project, where I had to deal with a very large space that required a bold statement—not quite what I felt like doing at the that time.

Big things?

Yes, these days I feel drawn towards making works like Recollection with the hair, or even those little objects I made at the Shaker community. I feel it is more appropriate for our times. People have become more aware of the body’s fragility, and the work has become more humble in a sense.

They occupy space by giving a sense of the activities of people living in and using it, rather than by physically imposing themselves.

The redeeming factor in the Capp Street installation was its simplicity. In a sense it is similar to Light Sentence , which is quite spectacular but very simple. Neither of these works are about the glorification of power structures, but rather a critique of those dehumanizing institutions and their effect on our existence.

It’s a square enclosure of wooden “cages” which is empty in the middle.

There were four very imposing wooden columns interrupting the space. I had somehow to integrate them into the work, so I constructed an enclosure of wooden cages between them. Every cage had a light bulb lying at the bottom, and I used a computerized device which dimmed the light bulbs on and off in a quick, random sequence. I amplified the buzzing sound of the sixty-cycle current going through the bulbs. There was something unsettling about it because there was such chaotic and mad activity within the regimented structure of the cages. It felt as though it was about to self-destruct. It’s called Current Disturbance .

Do you think the humbleness you speak of is something particular to you or do you sense that it’s more widespread?

It is a feeling I have been picking up for a while.

Do you want to say anything else?

It is refreshing to be interviewed without once being asked to explain my work in relation to where I come from. Most people who interview me seem to have this journalistic attitude that wants to explain or validate my work specifically in relation to my background.