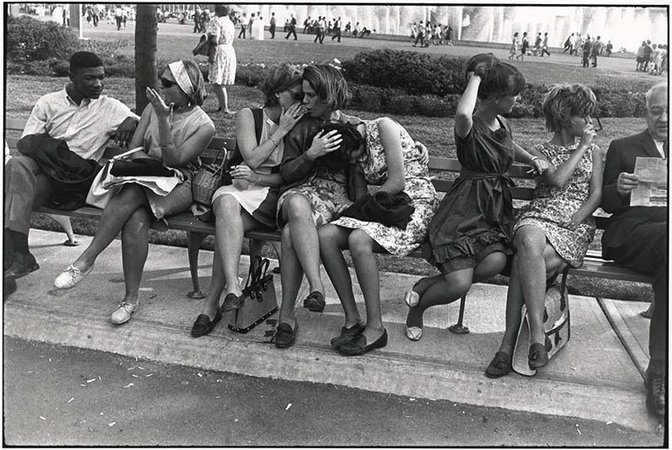

The first time you see a photograph by Garry Winogrand , the prolific documenter of the mid-century American street who has a restrospective opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this month, you might pause and think, “Huh, lucky shot.” Everything aligns just so. Three women with bouffant hair, for example, in a photo from 1961, form a V formation like migratory birds, clipping towards the lens in white pointed heels and knee-length skirts, each clutching big handbags and beaming identical looks—something between heavy-lidded bedroom eyes and glaring death stares. In the edge of the frame are men in cheap suits, and gleams of light flashing like knives in the windows of gridlocked cars.

But then you encounter more of Winogrand’s teeming spectacles—a wind-swept woman issuing from the street, about to make a left turn in front of a “No Left or U-Turn” road sign, or else a pudgy, ovine boy in Texas as round and dim-looking as his adjacent sheep companion—and you realize that these are more than a few well-chosen moments. Winogrand’s genius lay in identifying the visual rhymes and assonances of the street again and again as he roved around, a dogged reporter of the everyday.

Born in the Bronx in 1928, Winogrand was a weather forecaster for the army and then a Columbia University student under the G.I. Bill. Studying in that school's painting department while also auditing photo classes at the New School and CUNY, Winogrand soon sided with the camera, and his own career followed the graduation of photography from a journalistic tool to the realm of fine art. By 1967, the legendary MoMA photography curator John Szarkowski included Winogrand in the landmark exhibition “New Documents” along with Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander , calling Winogrand a “central photographer of his generation.” Here, we have a closer look at the work of this clear-eyed wanderer whose photographs recorded the vast breadth and restless energy of 1960s America.

WINOGRAND, UNEDTITED

Some photographers treat their cameras like professional baseball players do their bats: only swinging at something when at the plate. But for Winogrand, every minute was game time. Roving through the streets, he hung two wide-angle Leica’s around his neck and wore a safari jacket stuffed with dozens of canisters of 35-millimeter film. He exposed some 20,000 rolls over the course of his life, shooting at a manic pace. He could exhaust an entire roll while traveling down a single city street block. “Being married to Garry was like being married to a lens,” his first wife recalled.

Winogrand didn’t develop film immediately after his trigger-happy shooting sessions. Instead, he would wait, a year or two, allowing the memory of the day to fade completely. “If I was in a good mood when I was shooting one day, then developed the film right away, I might choose a picture because I remember how good I felt when I took it,” Winogrand explained.

Upon his untimely death at the age 56, he left 6,500 rolls (250,000 images) undeveloped. (Volume-wise, he would have been better suited for our age of Instagram and endless streams of digital photographs.) Curator Leo Rubinfien shuffled through over 20,000 contact sheets and nearly a million pictures for the Winogrand's Met retrospective.

STUDENT OF AMERICA

"You could say that I am a student of photography, and I am" Winogrand said, "but really I'm a student of America." Winogrand documented a seemingly endless parade of his countrymen with his camera: business tycoons, soldiers, antiwar protestors, feminists, zoo visitors. He never shot with any particular motive or show in mind, and his images share this quality, hewing to no single, pointed focus. Critics originally found fault in this approach, calling the densely packed pageants diffuse and formless. Today, though, we appreciate them as modern-day history paintings, thick with interweaving subplots and inchoate, evolving action, with meaningful sideward-glances exchanged on the periphery.

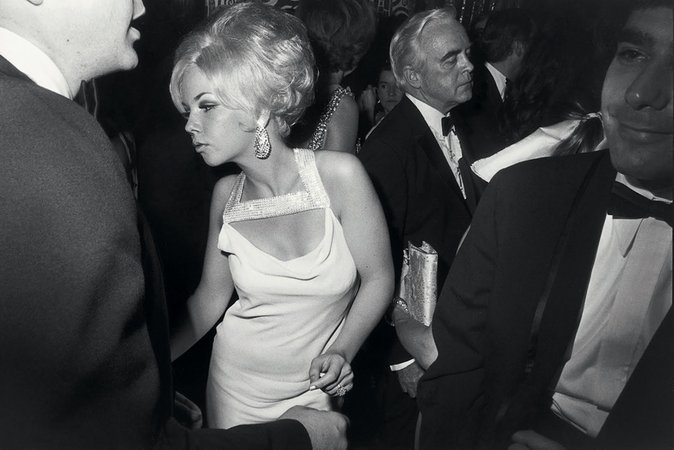

At a posh dance party, for example, a young platinum blonde swivels her waist and purses her lips. Further in the background, a tuxedoed old man with hair as pure white as her own also wears the same downward cast glance and thin-lipped expression. Packing in as much information and synchronicity into the frame as it can fit, Winogrand charged the photos with wild energy and opened up the picture to more visual resonances, and moments of serendipity.

This animated, buoyant atmosphere, however, dwindled in the photographer’s later years; photographs from Texas and Los Angeles hold a darker allure. In the picture Day of the Dead (1979), for instance, a woman lies immobile on the side of a Los Angeles road as a Porche rolls by.

WOMEN ARE BEAUTIFUL

There was one notorious body of work for which Winogrand did select and sequence himself: “Women Are Beautiful,” a 1975 book published of women doing activities, from dancing to demonstrating. Often, they are buxom women in snug dresses, or long-limbed ones in short skirts. Indeed, the series incited the censure of some critics as being misogynistic, or else objectifying. An off-kilter angled photograph centers on a woman in a phone booth with a long leg propped up and face blocked out by the bar. What’s the line between celebrating women's liberation and indulging hetero male erotic fantasy? In the cover photograph of the series, a woman tilts her hair back laughing with an ice cream cone in one hand. Behind her is a headless mannequin in a suit and tie. Does she get the last laugh?

Winogrand didn’t see his project in antagonistic terms, however. “Whenever I’ve seen an attractive woman,” he said, “I’ve done my best to photograph her. I don’t know if all the women in the photographs are beautiful, but I do know that the women are beautiful in the photographs. By the term ‘attractive woman,’ I mean a woman I react to positively… I do not mean as a man getting to know a woman, but as a photographer photographing.”

Recently, the curator Rubinfien told the New York Times that, in the best of Winogrand’s photographs, “you don’t know whether to feel elated or horrified, and you feel both.” In the same way, we are not sure if the images of Winogrand's women are condemning or celebratory. We are left with something messier, and perhaps more interesting.