When is a cat a work of art? Though it may seem little more than the latest and perhaps most radical attempt to extend the definition of “readymade” to all of life, presenting live animals as art is actually something of a classic conceptual strategy at this point. Ever since such Dadaist exploits as Salvador Dalí’s 1938 proto-installation Rainy Taxi (Mannequin Rotting in a Taxi-Cab), which included live snails and plants watered through the roof of a converted cab, artists from a variety of movements and styles have repeatedly taken up the live animal as both a performer and subject—in the process provoking questions of ethics as well as presenting fundamental challenges in presentation, documentation, and archivization. (Not to mention the issue of installing a live animal above your couch.) Recently, however, artists like Pierre Huyghe and Darren Bader have been exploring this gesture in novel ways—making for a ripe moment to revisit some of the most influential works of “animal art” from the past century.

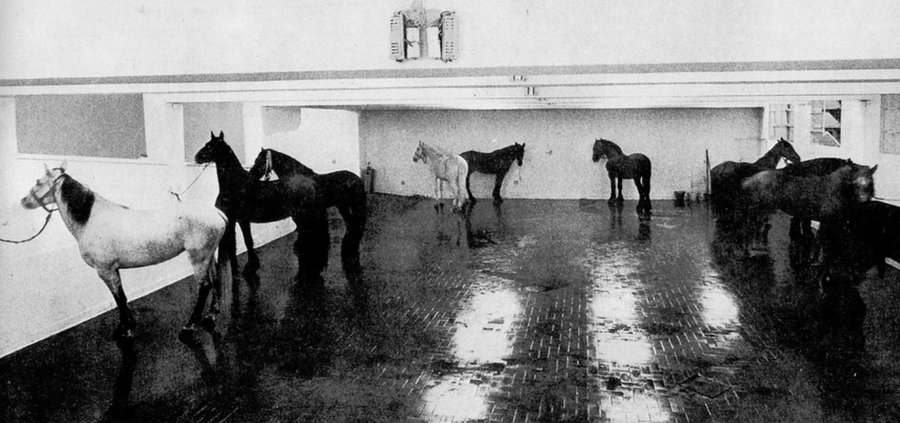

JANNIS KOUNELLIS’S UNTITLED/12 HORSES (1969)

Perhaps the most celebrated early example of animals-qua-art came out of the Arte Povera movement, the group of Italian avant-garde artists who laid the groundwork for what we would now call “installation art” between the years of 1967 and 1972. Greek expat Jannis Kounellis, a central figure in the movement, took the movement’s use of humble found materials into new territory with this seminal 1969 piece, which simply consisted of a dozen live horses hitched side-by-side to the walls of Rome’s Galleria l’Attico. Both captives and captors of a kind, since their sheer size and physical power had an imposing effect on gallery visitors, the animals were presented as they were, far from visions of perfection in marble or paint. Reactions to the work varied widely, with the horses compared to everything from the Parthenon frieze to rows of new automobiles parked in their bays, although Kounellis himself later said that the work was meant to invoke “the spirit of the Enlightenment.” Re-staged at the 1976 Venice Biennale, the piece was a landmark in performative, time-based installations.

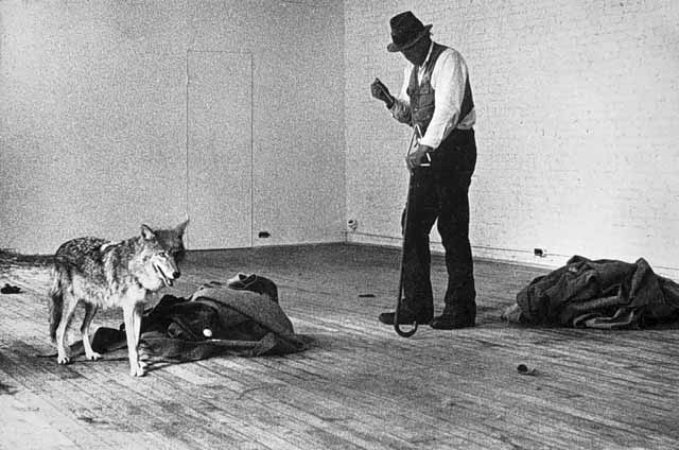

JOSEPH BEUYS’S I LIKE AMERICA AND AMERICA LIKES ME (1974)

When it comes to working with animals, some artists are content to simply bring the animal into the gallery context. Others take a more active role. For his 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me, Joseph Beuys was rushed via ambulance from the airport to René Block Gallery in New York, where he shared a room with a live coyote for three days, engaging in various actions that incorporated the canine as both observer and participant. The performance—which involved props that included a felt blanket, a cane reminiscent of a shepherd’s crook, a flashlight, and copies of the Wall Street Journal that were delivered daily—was far more concerned with the shamanic hagiography of Beuys’s practice than it was with the coyote as a living being, but it was the precarious negotiation between man and feral beast necessary to share the space in peace that lent the work its drama and heft. This sense of equality was critical to the piece, as both actors were fully able to affect the course of the performance, creating a sense of danger not fully resolved until Beuys’ exit.

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ’S COCK-A-BUNNIES (1982)

Whereas animal-based artworks tend to be carefully planned performances, undertaken or at least received in the controlled setting of the museum or gallery, David Wojnarowicz’s “cock-a-bunny” intervention at MoMA PS1 operated in a different mode entirely. Feeling spurned after the institution neglected to include him in its 1982 “Beast Show”—and perhaps inspired by ABC No Rio’s Animals Living in Cities exhibitions of 1979 and 1980, which included chickens, pigeons, and cockroaches in the space alongside more traditional works—Wojnarowicz showed up at the opening and surreptitiously released dozens of his hideous living constructions into the museum. Made by attaching a cotton-ball tail and paper rabbit ears to live roaches, Wojnarowicz’s cock-a-bunnies proved to be one of his most memorable early attacks on what he saw as the complacency and corruption of the New York art world.

DAMIEN HIRST’S A THOUSAND YEARS AND IN AND OUT OF LOVE (1991)

Damien Hirst is best known as a virtuoso of dead animals, from the trophy-like vitrines of his Natural History series—featuring sharks, sheep, and cows preserved in formaldehyde—to his various Entomology works that use thousands of insect carapaces to create colorful, macabre displays. But in two of the pieces that launched his career, both from 1991, the animals in question were alive… at least for a while. In A Thousand Years, Hirst placed a severed cow’s head in a vitrine an allowed it to rot and be infested with maggots, which over the course of the piece then turned into flies and flew to the top of the vitrine, where they were killed by a bug zapper. The concept for In and Out of Love was similar, only it also incorporated thousands of butterflies that were born, briefly lived, and died in the exhibition space. Both pieces laid the foundation for his future work by bluntly foregrounding life processes, and metamorphoses (both conceptual and physical), centered on the altered life cycle of the insects that culminated in their transformation from mere dead bodies into works of art. The complete level of control over the entire lives of hundreds of creatures that Hirst exhibited in these works remains shocking today.

ADEL ABDESSEMED’S DON’T TRUST ME (2008) AND USINE (FACTORY) (2009)

Infamous for his jarring and often upsetting compositions, Adel Abdessemed has made a name for himself in part through his video works exploring the brutality inherent to basic survival. The most controversial of these pieces are Don’t Trust Me from 2008, which showed a man using a sledgehammer to bludgeon a series of farm animals to death in front of a brick wall , and Usine (Factory) from 2009, in which a veritable menagerie of animals including snakes, toads, roosters, and pit bulls were pitted against one another in an uneven battle for survival. Bloody and hard to watch, the works showcased the most familiar form of human-animal interaction: crude physical violence and spectacular death, a dynamic that people are largely shielded from by their mediated experience of the food chain, picking up their cold cuts in the supermarket and oxblood brogues at the shoe store. Spurring protests, boycotts, and exhibition cancellations around the world, the videos—like Hirst’s vitrines—took artistic license taken close to its logical conclusion, in which artists feel it within their power to take the life of another for the sake of their work. The ethical questions embedded within the works remain implacably provocative.

DARREN BADER’S IMAGES (2012)

The works of puckish conceptualist Darren Bader often reference the ephemerality and instability of artworks, a concern that certain pieces from his 2012 MoMA PS1 show Images brought quite literally to life: in one room of the museum, the artist “installed” a group of live cats, accompanied by an equally vivacious iguana in the room next door, all available for adoption. These “sculptures” (Bader’s preferred term) were free to loll and play on the couch and in the cardboard boxes provided, giving only a passing sniff to the copy of Richard Avedon’s Portraits of Power lying on the ground. Arguably the simplest artistic gesture one can make with a living animal (we’ll leave it to you to decide if it’s the most profound), these readymade sculptures served as a contemporary update of Kounellis’ earlier attempts to expand the purview of art—an effort that in many ways defines the trajectory of modern and postmodern art history.

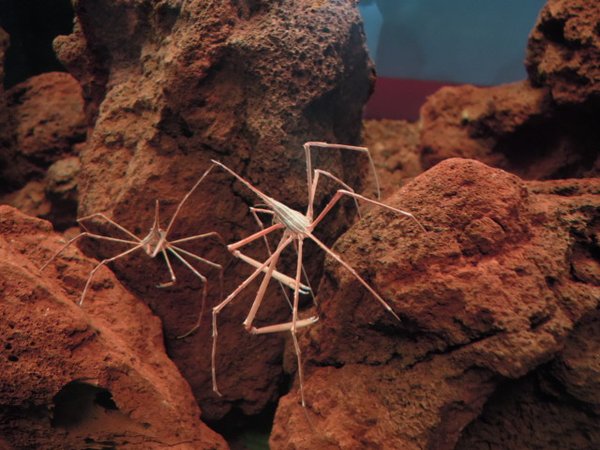

PIERRE HUYGHE’S ZOODRAM (2010) AND UNTITLED (2012)

Even given the contemporary glut of works utilizing live animals, there is perhaps no artist that has as fully incorporated the gesture into their practice as the French artist Pierre Huyghe. While his oeuvre has ranged across media and movements, recent years have found him increasingly interested in the potential of nonhuman actors. His midcareer retrospective—currently on view at LACMA—features many of these works, including his Zoodram series of curated aquaria (housing, for instance, a hermit crab living in a hollow copy of Brancusi’s sculpture of a woman’s head, Muse Endormie), his intentional importation of the flu virus into the gallery setting, and works featuring his much-loved white Ibizan hound named Human. Usually seen with one of her forelegs painted Day-Glo pink, the dog has wandered several of Huyghe’s installations and retrospectives since she first appeared in his Untilled piece at dOCUMENTA 13 alongside a reclining nude with a functional beehive for a head.

Though one could certainly think of these works as operating in the mode of the readymade (with Human’s pink leg perhaps analogous to Duchamp’s fake signature on his Fountain as a barely there alteration of the found thing), the specificity and sensory intensity of Huyghe’s installations tends to blend the boundaries of individual works so as to make the entire exhibit a single, multifaceted work, or ongoing performance of many smaller acts. In his work, these interactions with nonhumans are always negotiations, intersections in space and time between beings possessing their own agendas and concerns, helped along by what little understanding we struggle to achieve.