The photographers Ralph Gibson and Larry Clark met in 1967 in New York and became instant friends, united by their shared love of the medium and its unique expression in American art. And though they approach photography in divergent ways—Gibson, a former assistant to Robert Frank and Dorothea Lange, shoots classically composed erotic tableaux; Clark, most famous for directing the film Kids, is a master of shocking vérité—their lives have now been intertwined for more than 50 years. This relationship is now the focus of "Ralph Gibson and Larry Clark: Friendship, Photography, and Films," a new exhibition at São Paulo's Museum of Image and Sound.

When the two first crossed paths, their trajectories were already quickly forming. Having learned photography in the Navy, Gibson moved to New York from Los Angeles and briefly worked out of Magnum's office when he was invited by Frank to help him on his 1969 film Me and My Brother. Larry Clark, who had first picked up a camera to help in the family baby-portrait business, had just arrived in town having been discharged from the Army, where he had served in Vietnam as a stevedore. Clark had clandestinely begun his major work—which was later to become the famous series Tulsa—as a teenager in Oklahoma, while Gibson was fully underway making images for his breakthrough 1970 book The Somnambulist. They were both working outside of the conventional definitions of photography at the time.

Not finding an outlet for his work—photography galleries were exceedingly rare then—Gibson decided in 1970 to launch his own publishing house, which he called Lustrum Press. The self-published Somnambulist was his first book, and it was an instant hit—enabling him to pay the nine months’ of back rent he owed at the Hotel Chelsea. The success of the book convinced him that he could produce the same result for his friend Larry, and the autonomously printed format suited them both exceptionally well: it allowed them to freely exhibit their provocative work, avoiding censorship and bypassing the established publication world.

As Gibson says, “The rest is history.” And their photography, indeed, has become a part of the American canon.

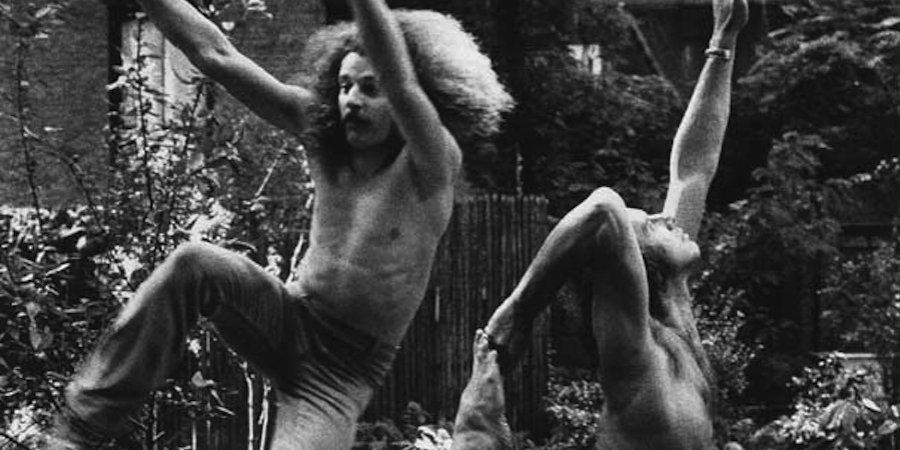

Drawing on an immense cultural framework informed by painting, music, literature, and architecture, Gibson is a rigorous formalist whose images teem with drama that is only intensified in deep black and white. (The alchemy of light on film has been a constant fascination to him.) His frame is always taut, and there is never unwanted information in his photographs. In this sense, Gibson's work is subtractive. Shadows are transformed into shapes that inform the content. Details and unexpected moments are equally important: a fork, a tablecloth, a man’s shoe, a geometrical element, a simple human gesture. Above all, he is attracted by the sensuality of lines and the compositional aspect of shapes, particularly the curves of a woman’s body. Like the Surrealists, Gibson transforms an insignificant instant into an image of importance.

Clark’s photographs and films, on the other hand, address the topic of American youth. But far from following the traditional portrait genre, Clark tells stories about relationships through his subjects' everyday actions, collectively constructing narratives of hidden communities. Tulsa—both the book of that name and the accompanying film—documents the young, marginalized inhabitants of Clark’s hometown in Oklahoma, with the photographer firmly ensconced in the center of the story. (Gibson refers to all of Clark’s images as being self-portraits.) The close relationship between Clark and his “models” is made clear in the intimate character of the work, which caused an uproar for its frank depiction of sex, drugs, and violence. “Why can’t I tell the truth, the truth, the truth?” asks Clark.

Gibson and Clark are both minimalists in their respective manners. They are direct and intimate, and their framing is tight. Not by chance, both have used Leicas throughout their careers, and neither crops or manipulates their images. And while Clark uses photography as a way to tell a tale—“as if in a film,” as he puts it—Gibson can be seen as a raconteur of another sort: when viewed together, his sequences form an open-ended, dreamlike narrative. While Clark’s work leaves nothing to the imagination, Gibson’s activates our innermost fantasies.