… spectators are chilled by its apparent lack of feeling or content. ritics, attempting to describe this new sensibility, call it Cool Art or Idiot Art or Know-Nothing Nihilism. That a new sensibility has announced itself is clear, although just what it consists of is not. – Barbara Rose in “ABC Art,” Art in America , 1965

Minimalism, now recognized as one of the signal artistic strategies of the 20th century, was called many things in the 1960s: ABC Art, Literalism, Primary Structures, Specific Objects, Reductive Art. What was clear then was that the mute, unadorned, and often raw three-dimensional objects that were suddenly dominating many galleries (mainly in New York) were a world away from both the brushy, heart-baring heroics of then-waning Abstract Expressionism and the slick irony of the ascendent Pop artists.

Critics, curators, and even the artists themselves were trying to categorize the fresh approach, but it was actually a British philosopher, Robert Wollheim , who indirectly coined “Minimalism" in “Minimal Art,” a 1965 essay in Arts Magazine assessing the rise of a new kind of art—objects with “minimal art-content.” Wollheim used the term as a nuanced catalyst for discussion, but Minimalism’s detractors found the reductionist term all too apt; the art critic and AbEx champion Clement Greenberg said, scathingly, that he hoped this new sculpture would learn “how to rise above Good Design.” But Minimalists themselves—many of whom hated the term, in particular Donald Judd —were not dissuaded, instead seeing themselves as having started a different aesthetic conversation.

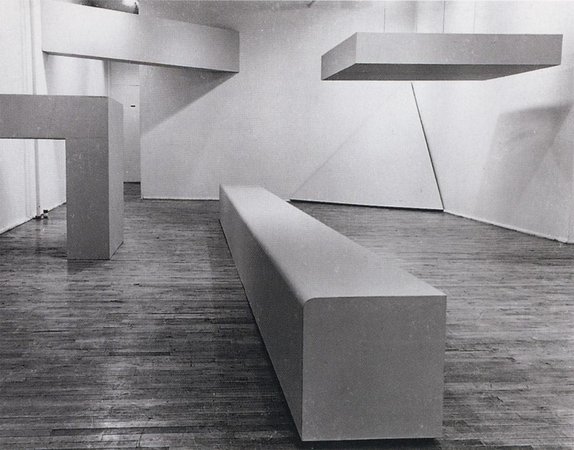

An early Robert Morris installation at New York’s Green Gallery, 1964

An early Robert Morris installation at New York’s Green Gallery, 1964

So, what was Minimalism, exactly? In the hands of the four canonical artists associated with the movement—Judd, Carl Andre , Dan Flavin , and Robert Morris —the work typically consisted of sculptural, bluntly geometrical works created from industrial materials (wood cubes, metal floor tiles, neon lights, thick felt drapes, etc.) that confronted viewers with their sheer, implacable objecthood, revealing nothing but their relation to the viewer's own physicality.

One of Minimalism’s main chroniclers, the art historian (and Greenberg protegé) Michael Fried , explained the movement’s conceptual concerns in his seminal 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood” by saying that its practitioners saw painting as “an art on the verge of exhaustion, one in which the range of acceptable solutions to a basic problem—how to organize the surface of the picture—is severely restricted…. The obvious response is to give up working on a single plane in favor of three dimensions.”

Andre, for one, had begun making these polemical sculptures in the late 1950s, but it was through shows in the early '60s at New York galleries like Green Gallery , Kaymar Gallery , Dwan Gallery , Tibor de Nagy , and Leo Castelli that this new sculpture gained notoriety. (“Don Judd” had his first solo show at Castelli in 1966.) Museums also embraced this new aesthetic. In 1966, the Jewish Museum held the important Primary Structures exhibition and the Whitney Museum included Minimalists in its American Sculpture: Selection I exhibition. American Minimalists were shown outside of New York with shows like Multiplicity at the ICA Boston in 1966 and American Sculpture of the Sixties at LACMA in 1967, and abroad in shows like Minimal Art , at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague in 1968.

Across the work that constituted Minimalism—including that by other artists associated with the sensibility, like Walter De Maria (land art), Robert Smithson (land art), Sol LeWitt (conceptual art), Tony Smith , and Frank Stella (painting)—the key attributes could be boiled down to three elements: shape, size, and material.

SHAPE

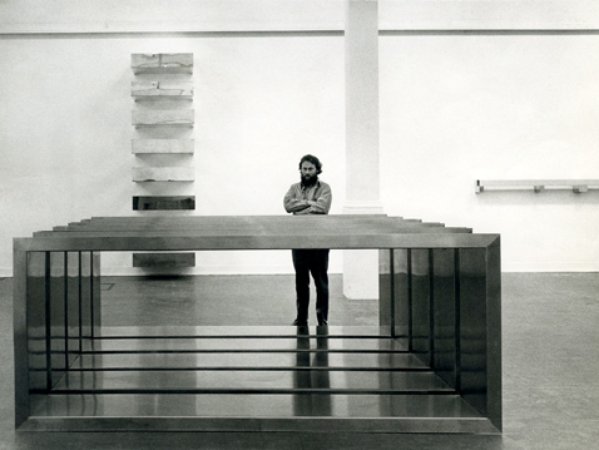

Donald Judd posing with his sculpture

Donald Judd posing with his sculpture

“The main virtue of geometric shapes is that they aren’t organic, as all art otherwise is," Donald Judd wrote in a 1967 essay with Lucy Lippard . "A form that’s neither geometric nor organic would be a great discovery.” Known for creating sculptures and installations that relied on the cube (or "box")—variations of which he made in plywood, steel, and Plexiglass—Judd also stacked pristine rectangular units at specific intervals up the length of walls, secure in the knowledge that the geometric shapes were not symbolic, representational, or meaningful in and of themselves. Carl Andre, too, stacked and placed pieces of timber and various metals into larger geometric forms, although he famously used the floor instead of the wall, radically removing sculpture from any form of pedestal or support; Dan Flavin created luminous, color-radiating sculptures from groupings of store-bought neons, while Robert Morris filled galleries with quadrilateral sculptures and draped thick sheets of sliced felt from walls, allowing gravity to determine its appearance.

Notions of symmetry and seriality were also important to the shape of the Minimalists' compositions, with symmetry employed not only to simplify production but also as a means of removing the need to balance any one part of the composition with any other. As Judd explained: “I wanted to get rid of any compositional effects, and the obvious way to do it is to be symmetrical,” adding that compositional effects “tend to carry with them all the structures, values, feelings of the whole European tradition. It suits me fine if that’s all down the drain.”

SIZE

Tony Smith’s

Die

(1968)

Tony Smith’s

Die

(1968)

In his essay “Notes on Sculpture,” Robert Morris quoted the artist Tony Smith responding to questions about Smith's six-foot 1968 steel cube work, Die :

Q: Why didn’t you make it larger so that it would loom over the observer?

A: I was not making a monument.

Q: Then why didn’t you make it smaller so that the observer could see over the top?

A: I was not making an object.

Much minimalist work related to human size, often in a way that suggested an unequal power dynamic. Morris wrote that this “positive value of large size… is one of the necessary conditions of avoiding intimacy.” Indeed Minimalist art often overwhelmed the galleries and museums in which it was installed. In her essay “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power,” the art historian Anna Chave noted that a large wood piece by Andre at Tibor de Nagy's 1965 Minimalism exhibition, Shape and Structure , nearly collapsed the gallery floor. Of the incident, Andre told Artforum , “I wanted very much to seize and hold the space of that gallery—not simply fill it.”

Not only was a lot of Minimalist work large in size, it was large in scale—it managed to filled space that it did not physically inhabit. The artist and critic Mel Bochner described this effect in his 1967 essay “Serial Art, Systems, Solipsism” from 1967: “For although [Flavin’s] placement of fluorescent lamps parallel and adjacent to one another in varying numbers or sizes is ‘flat-footed’ and obvious, the results are anything but.... Both Andre and Flavin exhibit acute awareness of the phenomenology of rooms. Andre’s false floors, Flavin’s demolished corners convert the simple facts of ‘roomness’ into operative artistic factors.”

The Minimalists’ desire (and ability) to capture space—and with it, the attention of viewers— was a major objection among critics to this new art. Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried’s main complaint of Minimalism was its sense of experience—or, as Fried would call it, "theater." (Greenberg thought, additionally, that Anne Truitt predated the Minimalists because her painted totems had an “effect of presence .” While the Minimalists did not think of their work as approaching theater, they were not only aware of but actively cultivating this experience of their works within their own terms.

MATERIALS

Dan Flavin’s

The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Robert Rosenblum)

(1963)

Dan Flavin’s

The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Robert Rosenblum)

(1963)

One important early Minimalist work was Dan Flavin’s 1963 The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Robert Rosenblum) , which was first shown in 1964 at the Kaymar Gallery in New York. Installed at a sharp diagonal, rising from the bottom of the gallery wall, Flavin’s neon piece was assertively more than just a light fixture. Though the work’s electrical components were hidden, the bulb was left unaltered and bare, allowing the work’s cool white light to transform the ambiance of the room; yet, because of the placement and abrupt angle on the gallery wall, this common industrial object was clearly not intended for use—it was art.

Just as Duchamp ’s use of found objects had helped usher in an era of "non-retinal" art, Flavin’s ordinary bulb—and, by extension, the other Minimalists’ use of common, industrially fabricated materials—declared a “detachment of art’s energy from the craft of tedious object production,” as Morris put it. The artist’s “work," here, consisted of the ideas and decisions that went into the presentation of the object—an idea that Conceptual art would fully explore in the late '60s, early '70s.

RELATED LINKS:

Art 101: A Squiggly, Neon-Lit Guide to Post-Minimalism