A decade of tremendous change in the art world and beyond, the 1990s saw dramatic upheavals across all spheres, from the rising cultural dominance of grunge to the technological revolution introduced by the Internet—never mind the shifting of geopolitical borders following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavian Federation, and the brutal civil wars raging across Africa. And, perhaps above all, the unimaginable devastation wrought by the too-long-ignored AIDS crisis. It was a decade in tremendous flux, and this, of course, was reflected in the art being made at the time. To mark the New Museum's new "NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star" exhibition (curated by Massimiliano Gioni), we reviewed a few of the ways that the era's tumult made its way into contemporary art.

SILENCE = DEATH

Globalization, identity, and ideology were themes that many artists adopted—particularly in the United States, where the Culture Wars put a rising progressive class in conflict with a rear-guard right-wing that opposed many of the civil rights we take for granted today. Cultural conservatives, led by North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, vilified boundary-pushing artists like the photographer Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe (who died of AIDS in 1989), and sought to decimate funding for the arts. The art world, in turn, fought back with ever more provocative work expressing outrage at the disenfranchisement of minorities, gays, and women. Notably, the most indelible protest artwork of the era—the iconic “Silence = Death” power with its pink triangle—was created by the activist Silence = Death project as a work of agitprop.

PAINTINGS ARE DEAD!

In a reaction against the large, brash paintings that became popular in the ‘80s, artists became increasingly introspective as they looked to everyday objects and the people in their immediate social circles as subjects for their art. Artists like Nari Ward, who reclaimed discarded refuse from urban settings, and Gabriel Orozco, a Mexican artist who photographed quotidian scenarios gone slightly awry, achieved prominence for their ambiguously interpretable commentaries on poverty and consumer culture. Sculptor Robert Gober, meanwhile, took the act of finding introspective inspiration a step further by basing his work on specific subjects and memories from his life. Moving away from the speedy appropriation of mass-produced objects favored by previous artistic movements, Gober meticulously crafted domestic objects by hand, emphasizing the intrinsic impermanence of creature comforts.

SUBCULTURES RULE SUPREME

Other artists focused on capturing the various subcultures pocketed around the United States, which were surging with a noticeable energy and vitality. Photographers like Larry Clark, who got his start documenting bands of roguish teenage surfers and skateboarders (often during moments of reckless violence and illegal drug use) and went on to direct Kids, exposed the grittier elements of youth culture, prompting uncomfortable conversations about a rising generation that disregarded prevailing societal norms. This approach was echoed by the German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, who first garnered acclaim taking casual portraits of the young people he encountered as an exchange student in London. As popular magazines began to feature his photographs of gay pride parades and local club scenes, Tillman's status as an important social documentarian began to rise—crescendoing in 2000 when he became the first non-British artist to win the Turner Prize. Like Tillmans, photographer Nan Goldin focused on capturing subcultures in snapshot style, chronicling the travails of drag queens and drug-addled bohemians caught in intimate moments.

SEX LEAVES THE BEDROOM FOR THE GALLERY

Goldin and other artists' emphasis on public and private transgressions of normative behavior was indicative of a larger movement. As the nation suffered through the throes of the AIDS crisis—with LGBT groups marching on Washington to demand government action—sexual liberation and identity politics became themes of critical importance to artists of the decade. Progressive and politically challenging artists like Lina Bertucci and Ida Applebroog created cartoonish paintings that tackled issues of gender and sexual violence, bringing feminist thought to the fore. Other artists, however, took a different tack, like John Currin, whose paintings of voluptuous women with exaggerated figures did more to reaffirm sexist stereotypes than overturn them.

IDENTITY POLITICS ENTERS THE MAINSTREAM

As the country become increasingly diverse—and divided, with events like the Rodney King riots inflaming debates over racism in America—a number of artists rose to prominence in the 1990s who making art that sought to challenge and expose the underlying racial stereotypes that pervaded society. Lorna Simpson began her artistic career working as a documentary street photographer, though she soon transitioned to a text-based practice that featured photographs of anonymous women (and occasionally men) paired with extracted phrases that urge the viewer to question that preconceived associations surrounding race and gender. (Her artistic approach has since expanded to incorporate a variety of media, including painting and video works.) Similarly, Glenn Ligon uses language as a means to revisit assumptions surrounding race, often appropriating the words and phrases of writers and other storytellers ranging from comedian Richard Pryor to Zora Neale Hurston. Other artists, such as Coco Fusco and David Hammons, also expertly targeted the pressure points of the typically conservative and overwhelmingly white art world with their work, aiming to expose social and cultural inequalities. The 1993 Whitney Biennial famously foregrounded questions of identity, including controversial works such as Daniel Joseph Martinez's museum tags bearing the words "I can't imagine ever wanting to be white." The exhibition was savaged by critics at the time—in Time magazine, Robert Hughes described it as a "fiesta of whining"—but, with the benefit of hindsight, it is now recognized as a landmark in the history of contemporary art.

THE RISE OF RELATIONAL AESTHETICS

The technological boom that occurred at the start of the decade also had a dramatic impact, as the rise of the home computer and the spread of the Internet made it easier than ever before for cultures and countries to interact with each other. As the distances between communities symbolically shrank, the scope of the art world grew, as artists’ work became accessible to wider audiences. In response to this growth, the idealistic future promised by new technologies was in turn co-opted by numerous artists and art theorists who emphasized the shared nature of collective experience. In addition to the artists who began incorporating the Internet directly into their work, some, like Rirkrit Tiravanija and Andrea Zittel, began making art that fostered social engagement between viewers. Tiravanija, for example, would often create installations filled with food and cooking materials in which visitors would be encouraged to share meals together, while Zittel made livable and functional works that enabled enmeshed interactions with the surrounding environment. Passive viewing done at a remove from the artwork was replaced by an interactive experience, inaugurating a “social turn” in contemporary art that continues to this day.

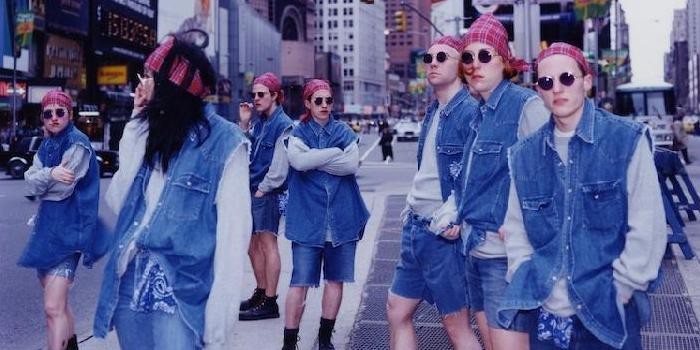

ARTISTS EMBRACE CELEBRITY CULTURE

This attempted flattening of social hierarchies by relational artists was not without its encumbrances. As the art world gained widespread attention around the world—sparked in no small part by the emergence of the Young British Artists in the late ‘80s—individual artists became rising celebrities in their own right, collapsing the divide between high art and star status. Painters like Karen Kilimnik made work stemming from the influence of popular culture, creating cursory celebrity portraits, while Elizabeth Peyton took the practice a step further by painting portraits of celebs, musicians, and European monarchs alongside her significant others and members of her social circle, entrenching mass culture's idolization of celebrity in the realm of fine art while at the same time elevating her friends to celebrity status. Art Club 2000, a collective started in 1992 by art dealer Colin de Land and a handful of Cooper Union students, took a more subversive approach to culture's consumeristic attitudes, posing in group shots dressed entirely in clothes from the Gap, mocking both the retail chain's pervasiveness and the willful homogeneity of the retail chain's shoppers.