Yes, I dream of a better world.

Should I dream of a worse?

Yes, I desire a wider world.

Should I desire a narrower?

–Otto Piene, "Paths to Paradise" in ZERO 3 (July 1961)

Zero is silence. Zero is the beginning. Zero is round. Zero spins. Zero is the moon. The sun is Zero. Zero is white. The desert Zero. The sky above Zero. The night.

–excerpt from a 1963 poem by Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker

The postwar avant-garde is finally having its art historical moment. The last couple of years have brought consummate surveys of global art movements of the 1950s and '60s to museum audiences, ranging from Paul Schimmel’s "Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962" at MOCA to "Gutai: Splendid Playground" at the Guggenheim to "Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde" at MoMA. The moment now belongs to the so-called Zero (or ZERO) group, a loose convocation of international artists that sprang up in German in the 1950s under the leadership of Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker.

In 2010, a Sotheby's sale drew fervid interest when a collection of Zero works far surpassed their estimates. Now, the Guggenheim is leading a widespread reappraisal of the artists with the group's first museum survey in the United States, the acclaimed "Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-'60s." A complementary exhibition of work spanning Mack's career at Sperone Westwater has also generated critical excitement. As a primer on the group, here is a brief history of a movement without a manifesto.

BEGINNINGS OF ZERO Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker

Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker

Active from 1957-66, Zero was initiated in Düsseldorf by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene; Günther Uecker joined in 1961. While the three artists formed the “inner circle,” Piene emphasized that Zero was “not a group in a definitely organized way. There is no president, no leader, no secretary; there are no ‘members,’ there is only a human relationship among several artists and an artistic relationship among different individuals.”

The artists came together in their desire to move away from subjective postwar movements, like France's Art Informel and Tachisme, and instead de-emphasize the role of the artist’s hand to create art that was purely about the work's materials, and world in which those materials exist. In other words: light and space. Indeed, the critic Lawrence Alloway asserted that Zero “was the first artists' collaboration devoted to topics of light and movement.”

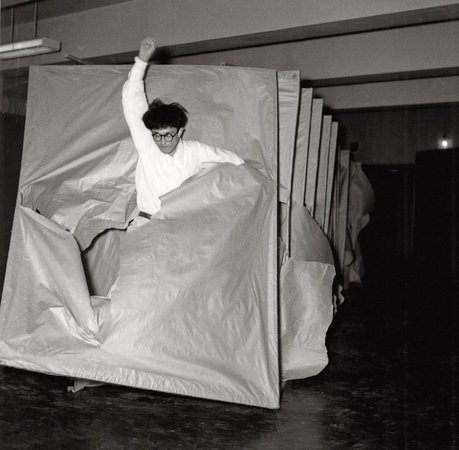

CONCURRENT MOVEMENTS Gutai artist Saburo Murakami creating At One Moment Opening Six Holes (1955)

Gutai artist Saburo Murakami creating At One Moment Opening Six Holes (1955)

Contemporaneous to Zero were various avant-garde movements in Europe and Asia, as well as North and South America, that found common aesthetic cause with the German movement. These included the Holland's Nul (Armando, Jan Henderikse, Jan Schoonhoven, herman de vries), France's Nouveaux Réalistes (Arman, Yves Klein, Daniel Spoerri), Italy's Azimuth (Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani), and Japan's Gutai group (Jirô Yoshihara, Shozo, Shimamoto, Kazuo, Shiraga, Atsuko Tanaka, among others); the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama and America's George Rickey also formed individual nodes in the orbit of Zero's influence.

(Nota bene: According to Guggenheim curator Valerie Hilling, Otto Piene stated that “Zero” should be used to denote the German group, with the capitalized “ZERO” standing for the larger network.)

Many of these international artists participated in Zero events, and in turn included members of Zero in their respective activities. Collaboration was key. As Günther Uecker wrote in ZERO 3, “Immediate experience comes only when we ourselves participate. To obtain widest participation, the production of art must cease to be limited to the individual, as it has been until now.”

Three artists who worked closely with Zero’s “inner core” were Klein, Manzoni, and Lucio Fontana. A generation older than the others, Fontana served as a father figure to both the Zero group and Azimuth; he was also an early supporter of Heinz Mack’s, having (unbeknownst to Mack) purchased the only work that sold in the artist's first Paris show. In addition to his artistic contributions, Klein also helped to solidify Düsseldorf-Paris relations, namely between Galerie Schemla (one of three then-new galleries in Düsseldorf) and equally influential Galerie Iris Cert in Paris. Piene dubbed Manzoni “Zero Mercury” because of the Italian artist’s voracious traveling between artistic hubs.

THE EVOLUTION OF ZERO "Vision in Motion—Motion in Vision" (1959)

"Vision in Motion—Motion in Vision" (1959)

ZERO had no simple, linear chronology. As the art historian Catherine Millet has written, “Zero consisted of a series of opportunities, of encounters and friendships which gave rise to three increasingly rich issues of a magazine, to exhibitions, and to events…. It was like a very long, deep wave that sent ripples right across the field of artistic creation.” Without a manifesto or strict membership, the activities of ZERO encompassed a range of artistic practices and, with an ebb-and-flow frequency, intermingled with other contemporaneous artistic movements.

The porousness of the Zero network was in part due to the fact that the artists created many of the exhibitions themselves, since there was no gallery system in postwar Germany to support the emerging avant-garde. As a result, Mack and Piene created their own means of promotion and display: one-evening pop-up exhibitions, the first of which was held in Piene’s Düsseldorf studio on April 11, 1957.

The fourth evening exhibition, held on September 26 of that year, was, according to Guggenheim curator Valerie Hillings, “momentous, less for the art shown than for a meeting that followed its close" at a bar called Fatty’s Atelier, located across from Galerie Schemla. It was there that they decided upon the name Zero. According to Piene, “From the beginning we looked upon the term not as an expression of nihilism—or a Dada-like gag, but as a word indicating a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning as at the count-down when rockets take off—zero if the incommensurable zone in which the old state turns into the new.”

For the seventh evening exhibition, Mack and Piene published the first of the three ZERO magazine-catalogues. Titled “The Red Painting,” ZERO 1 (April 1958) contained artists’ writings on color, monochrome painting, and “color as light articulation.” ZERO 2 (October 1958), titled “Vibration,” was published on the occasion of the eighth evening exhibition and was focused on “the relationship between nature/man/technology." ZERO 3 (July 5, 1961), titled “Dynamo,” was then published on the occasion of the exhibition “Edition, Exposition, Demonstration” at Galerie Schemla.

Toward the end of the '50s, Zero began to receive institutional attention. In 1959, "Vision in Motion—Motion in Vision," a show sometimes called the first large Zero exhibition, was help in Antwerp. Artists names were listed on the floor, below the work—an installation conceit repeated with dramatic aplomb in the beginning of the Guggenheim exhibition. Then, in 1964, Mack, Piene, and Uecker collaborated on an installation for dOCUMENTA 3, Lichtraum (Hommage à Fontana) [Light Room (Homage to Fontana)], which includes automated sculptural objects of varying heights, materials, and textures that are equipped with timers so they would turn on, move, and light up in a choreographed display. At one point, a projection of a Fontana painting—containing a single, vaginal slash—appears on one wall. The effect, experienced in the Guggenheim show, is startling.

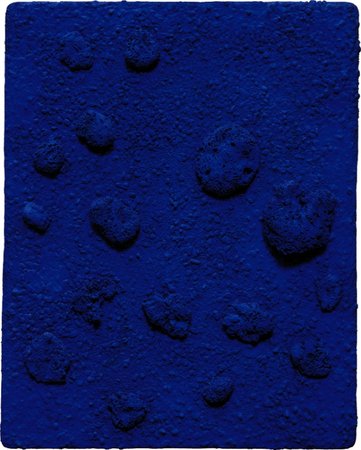

USE OF COLOR A Yves Klein sponge painting

A Yves Klein sponge painting

ZERO was unusual among postwar avant-garde movements in that it had neither a manifesto nor a definite national association, since the artists of the ZERO network did, despite their identification with other movements, hold ideological beliefs consistent with those of Zero. Key areas of artistic exploration included color (almost always monochrome), light, motion, space, and seriality.

For Zero, the use of monochrome served multiple purposes: it was a separation from the expressionistic and abstract works of Art Informel and other earlier postwar movements. Color was also part of the exploration of light, since color is a perception of light. The use of a single color emphasized a work’s surface as well as its highlights and shadows.

Various artists favored different colors for various reasons. In a 1959 lecture at the Sorbonne, “The Evolution of Art towards the Immaterial," Klein explained that “blue has no dimensions, it is beyond dimensions, whereas the other colors are not. They are pre-psychological expanses, red, for example, presupposing a site radiating heat. All colors arouse specific associative ideas, psychologically material or tangible, while blue suggests at most the sea and sky, and they, after all, are in actual, visible nature what is most abstract.” (Klein, famous for his blue works, also made pieces in red monochrome, and, taking the idea of heat further, even employed fire directly on canvas; Otto Piene painted with smoke, while Manzoni used soot.)

In contrast to Klein’s love of blue, Manzo made a case for white. “My intention is to present a completely white surface (or better still, an absolutely colorless or neutral one) beyond all pictorial phenomena, all intervention aligned to the sense of the surface. A white surface which is neither a polar landscape, nor an evocative or beautiful subject, nor even a sensation, a symbol or anything else: but a white surface which is nothing other than a colorless surface, or even a surface which quite simply ‘is.’”

OTHER THEMES One of Otto Piene’s Light Ballet works, installed in the Guggenheim

One of Otto Piene’s Light Ballet works, installed in the Guggenheim

In addition to its relationship to color, light itself was an important material for many Zero artists. Mack began working with light in the late '50s and, in 1958-59, created his first Licht-Reliefs (light reliefs), Lichtkuben (light cubes), and Lichtstelen (light pillars). Piene, meanwhile, had served in the German antiaircraft unit when he was 15 years old, and the Guggenheim asserts a direct link between his interest in light (particularly in his Light Ballet (Lichtballett) works) and his military experiences “of the night sky being lit up by the intensive aerial campaign” during World War II. Piene’s “ballets” are encompassing works, playing successfully with the visual delicacy and impact of the cosmos.

Seriality was also a preoccupation of the Zero artists, who used it as a way of organizing space, while hinting at the potential of limitlessness. This theme took many forms: Uecker’s nail-covered canvases and objects (often painted white); Schoonhoven’s gridded reliefs; Henk Peeter’s grid of feathers; Mack’s Lamella-Reliefs of slashed aluminum; even Jan Henderikse’s Bottle Wall (Flaschenwand) from 1962.

At times, seriality instilled a sense of movement, vibration, or kinetic energy within a work—as with the case of Piene’s Rasterbilder (stencil paintings) and Mack’s "Dynamic Structures.” Movement itself was at times at the forefront, notably in the works of Swiss artist Jean Tinguely.

ZERO IN AMERICA Heinz Mack at New York’s Howard Wise Gallery in 1966

Heinz Mack at New York’s Howard Wise Gallery in 1966

Zero infiltrated the United States in the mid-'60s, after Piene moved to Philadelphia in 1964 and New York the following year. In 1965, the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art held the show "Group ZERO." That same year, Howard Wise Gallery in New York showed works by Mack, Piene, and Uecker.

John Canaday's review of the show in the New York Times spoke to the strength of the work (“No theorizing is needed to back up the impact of these inventions”) as well as the clang of the ZERO network at large: “the attachments of the group, whose name indicates 'a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning' include some of the noisiest artists who seem to me to be most in need of cleaning up, with more joining every day. If this is a bandwagon, we may look forward to its transformation into a sinking ship from sheer overweight, but I would place a bet that Mr. Uecker and Mr. Mack will manage to stay afloat.”

In his review, the artist-criticDonald Judd relayed that “Since the United States is relatively inattentive to new European developments, this is the first Zero exhibition here.” He pronounced Mack, Piene, and Uecker all “able and convincing.” Coming from Judd, that’s a compliment.

TODAY AND TOMORROW Heinz Mack’s The Sky Over Nine Columns in Venice

Heinz Mack’s The Sky Over Nine Columns in Venice

The Zero artists continued to work independently after the group’s actively collaborative period ended in 1966. Sperone Westwater’s exhibition "Heinz Mack: From Zero to Today 1955-2014" (through December 13, 2014) offers a look into the last surviving Zero founder's work beyond the movement, with most of the pieces drawn from the artist’s personal collection. Recent visitors to Venice will also have seen Mack’s newest installation, The Sky Over Nine Columns, comprised of nine gold-mosaic columns, each standing 26 feet tall. It work continues Mack’s career-long examination of light and its environment.

Now, under the leadership of the ZERO Foundation, a global series of shows will continue the public resurgence set in motion at the Guggenheim. Upcoming shows organized by the foundation will be at Berlin's Martin-Gropius-Bau (March 21-June 8, 2015) and Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum (July 4-November 8, 2015), at once extending the movement's legacy and exemplifying the network's international footprint.