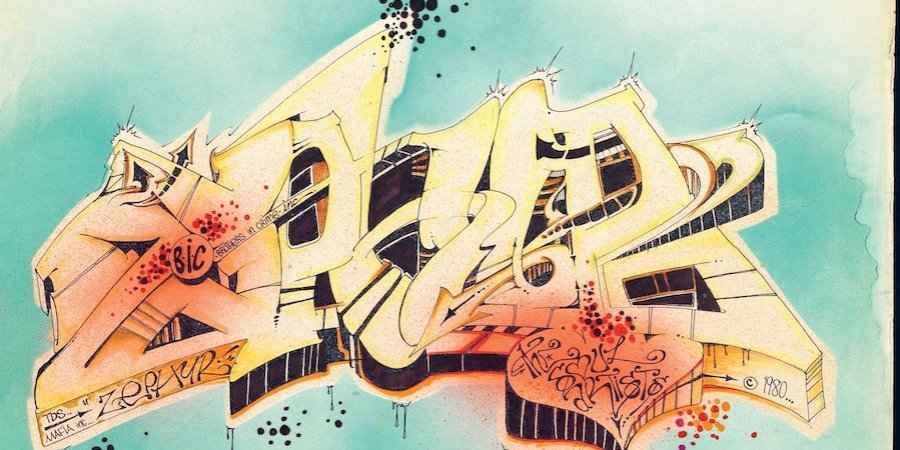

“Graffiti art is the true American art form,” said Aaron Goodstone, AKA the graffiti writer Sharp, at the press preview for “City as Canvas: Graffiti Art from the Martin Wong Collection” at the Museum of the City of New York up on Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street. Lady Pink, an artist whose given name is Sandra Fabara, noted that she started her graffiti career as a teenager. "Street art is the world’s biggest art movement," she said. "It proves you can make art and change your environment.”

Upon a moment’s reflection, these extravagant claims turn out to be true. Graffiti art has few direct precedents in European modernism, save perhaps Dada concrete poetry and, going a bit further back—as Sharp pointed out—medieval manuscript illumination. All the more telling, then, that graffiti art remains on the fringes of the official fine art world, and is now given a bit of overdue attention at a local history museum rather than at one of the art museums a little bit further downtown.

Is the stuff too transitory? Too extravagant? Too ghetto? It thrives all the same, as a global, populist phenomenon. “City as Canvas” features still-vigorous relics of the form’s earliest days, a historical selection of 150 works from the 360-item collection assembled in the 1980s by the East Village artist Martin Wong (1946-1999). The lavishly illustrated 240-page catalogue, published with Rizzoli, includes essays by exhibition curator Sean Corcoran, Street art expert Carlo McCormick, and recollections by “Wild Style” (1983) director Charlie Ahearn and graffiti writers Chris “Daze” Ellis and Lee Quiñones.

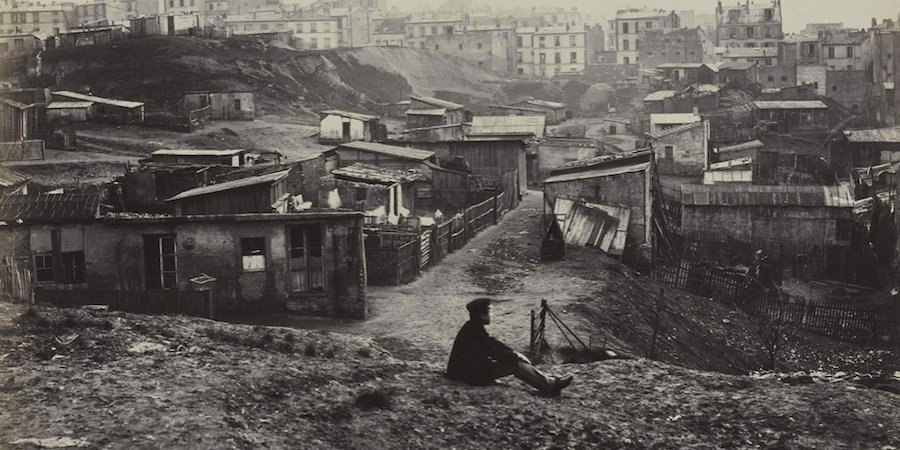

A different vanished city—Paris—is the subject of the expansive three-gallery survey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of 100 photos from the 1850s and ‘60s by the pioneering French photographer Charles Marville (1813-1879). An illustrator who specialized in drawings for woodcuts of landscapes, city views, and art reproductions, Marville took to photography with a vengeance a mere 11 years after its invention. No aristocrat (like so many other photo pioneers), Marville immediately snagged paying jobs doing photos for commercial picture albums and, more importantly, working as official photographer for the city of Paris.

Almost incredibly, then, Marville was hired to document the city neighborhoods that Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann had slated for demolition as part of their radical modernization of the city, as well as the new and extravagantly landscaped Bois de Boulogne park. He had a remarkable “eye”—the photos are beautiful and fascinating, but that goes almost without saying. Two things make them especially interesting: first, that they are “official” images produced for government archives (where they were promptly buried for more than a century), making them a literal expression of the dominant worldview; and second, that Marville took to the camera as a machine that would magically reproduce the already-well-known image bank, especially in his park views, which echo work by the Barbizon painters and other landscapists.

These are distinctly postmodern notions, odd to find in early photography—though maybe it’s just me, since the Met’s show last year of Julia Margaret Cameron seemed to prefigure none other than Cindy Sherman. In this vein, apropos Marville, we have the current exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery on West 57th Street of new color photographs by the German artist Thomas Struth. The show features views taken at our own latter-day Bois de Boulogne, Disneyland, works that the artist ingeniously describes as explorations of “the process of imagination and fantasy.” These photos, some of which are produced in editions, are priced at $120,000-$240,000.

I can’t resist a contemporary suggestion for the Met regarding its Marville installation. The next time the museum mounts a show like this, it should make high-contrast floor-to-ceiling blow-ups of the typically hard-to-see 19th-century prints and wallpaper the galleries with them, before installing the photographs in the normal way. One such enlargement already graces the entry to the show as a kind of marquee. The point would be to highlight the barely visible details in the pictures, which were after all meant to be documents as much as the fetishized, collectible objects that they are now. We could then see in detail, for instance, what the wall label informs us is a street poster advertising a collapsible umbrella “in the American style,” but that is nevertheless imperceptible in the actual print.

I would commend this idea, though admittedly without much hope of success, to the exhibition’s estimable curators, Sarah Kennel of the National Gallery of Art, where it has already appeared, and Met curator Jeff L. Rosenheim. They and the National Gallery has produced an invaluable 256-page catalogue, where the pictures are perhaps more easily perused.

Such a wall-to-wall strategy has been well employed, in his own way, by Wade Guyton in his new show at the Petzel Gallery on West 18th Street in Chelsea, his first New York solo since his exhibition at the Whitney Museum in late 2012. Here are five untitled paintings, all efficiently produced just last month using the artist’s signature Epsom inkjet method. Printed out first black then white, measuring nine feet tall and as long as 42 feet, the pictures butt up against the corners of the galleries, transforming the space into a kind of pictorial arena.

Manet’s paintings of bullfights gave us a field of life and death, and it’s hard not to think of Guyton’s installation as an arena of capital, an example of the artwork as a copy of nothing, as value conjured from the ether, 21st-century-style, i.e. from a digital file. Apparently priced north of $500,000 each and sold in pairs, the works are easily among the largest gestures in an era of baroque macho conceptualism. Though all abstract painting today is rooted in Abstract Expressionism—it was Adolph Gottlieb who once said, “The most extreme thing I could think of doing was to divide the canvas in half”—only grand gestures like Guyton’s seem able to rise above the background noise of ordinary art. That’s why it looks so much like genius.

Walter Robinson is an artist and art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). His work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, Dorian Grey, and other galleries. He can be reached at walter@artspace.com. Click here to read his previous See Here column on Artspace.