These days, if you ask Los Angeles-based artist Chris Johanson about his practice, he'd likely tell you, in his Northern Californian drawl, that he's just trying to make simple, peaceful art. But the self-taught street artist and painter wasn't always so peachy-keen on positivity. A part of San Francisco's Mission School Art movement, Johanson began his career with the angst of a teenager—and the rendering skills of one too. He has since become a darling of the art market, celebrated for the naive, doodle-like paintings he terms "documentary pictures," his enigmatic personality, and an attitude towards the art world that is as much outsider and sincere as it is biting and critical—not to mention hilarious.

Gaining recognition in the late '90s, the artist's work has been shown in numerous international exhibitions, including the Istanbul Biennial (2005), SITE Santa Fe (2002) and the Whitney Biennial (2002) with solo shows at the Malmö Konsthall (2011), the Portland Art Museum (2007) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2003).

In this excerpt from a 2013 interview with curator Corrina Peipon in Phaidon's monograph Chris Johanson, Johanson explains, in his idiosyncratic way, how his art wasn't always so happy and peaceful and reflects on his experience using artwork as a combatant, psychic medium for his anger and frustration with the world.

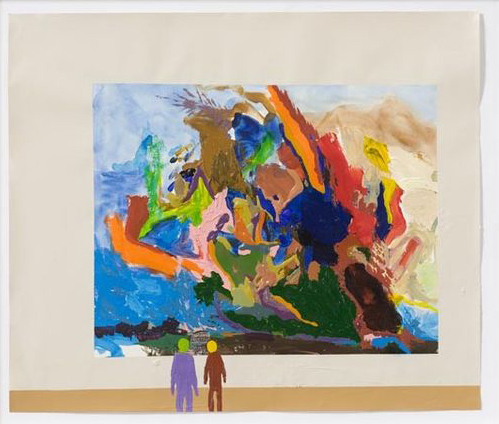

Possibilities (2017) installation view at Mitchell-Ines & Nash, N.Y.

Possibilities (2017) installation view at Mitchell-Ines & Nash, N.Y.

You said something a little bit ago, about how you think ugly is beautiful. I’m curious to know a little bit more about what that really means to you, and whether you mean that so literally as to say that you create an aesthetic that is intentionally ugly, or if you just think that there are some people who think your work is ugly? Is it the style that is ugly, or the ugliness in the subject matter?

Well, I have to think about this for a minute. I’m interested in so many different mediums, and I think that at the base of where I entered this whole thing, I felt that making things was going to be the place where I was going to say what the deal was with it. It was important for me to say: This has an importance to me, this has value. This stick figure making a salad and saying, ‘Hi! It’s really good to see you, I made a salad, I prepared a special salad for you!’ With just as few lines as possible, it shows this woman’s nice, loving smile to the person she’s talking to.

You know that I had serious problems with education, a hatred of schools and the way they are structured for certain kinds of people. So I had difficulties reading and writing when I was a kid, and I found art to be the place where I could make it the way I wanted to make it. That’s what was really important to me, to make things. Conceptually, I know now that what I was doing when I really was working all the time in San Francisco was making things that would appear not to have value. I wanted to make things that looked shitty, or looked harsh, or not beautiful, or off-putting. But at the same time I would sense that this is real, this is really important: ‘What do you mean that stick figure isn’t beautiful or a whole person? That stick figure has the same amount of feelings that you do!’

Living To Say Yes and No (2015)

Living To Say Yes and No (2015)

Are you saying you were trying to challenge or confront some kind of conventional notion of what should be valued or thought of as beautiful, so that you could successfully articulate this language with which you wanted to build a new world?

Yeah, I think that I was making stuff when I was in my early twenties that was harsh and crudely drawn, and I was doing that because I was reacting against, basically, what I thought was authority trying to tell me about the right way to live.

One time I got in a show that [was at] Glen Helfand['s]; he curated this show called ‘Museum Pieces’ (1999). I was just as surprised as anybody that I was asked to be in the show, because everybody else was like David Ireland, Harrell Fletcher, and John Rubin. It was a pretty academic kind of grouping of artists. It was at the De Young museum. Glen wanted me to be in the show, and I was happy to be invited. They wanted me to do a piece that was about the museum, and I was like, ‘What? I’ll be in the show, but I’m not going to do a piece about the museum, because I don’t make art about the De Young museum’. Now perhaps, if somebody said that I would think, ‘Whoa, it sounds interesting! Now I have a different relationship to art, art making, art history, myself, because then I was twenty-six or twenty-seven or eight, and now I’m in my mid-forties. But at the time I just had no idea what they were talking about. I was like, I can’t do that. I’ll cruise around the park for a month, I’ll ride around on my bike in the dark, I’ll watch elderly couples on walks and sitting together, watch the deadheads, and then I’ll make a piece about the park where the museum happens to be. And then I made this piece about the park. Then I was at this café, and the guy was all—it just came up in conversation, me and this person started talking about the show, and I went, ‘Yeah, I’m in this show…’, and this other person was like, ‘You’re in that show?’ Like there was…

Meaning your work wasn’t good enough or something?

Something like that or whatever. I’ve always hated that kind of stuff. I just don’t like that dialogue. It was so liberating to make art. But when I actually started to show art more, I think I wanted to be confrontational with people. At the start, I wanted to fuck with the idea of what could be considered art, because I had felt that in education in general, you know, I just had a chip on my shoulder. So for me it was a way of pushing buttons back. It was crudely drawn, and I was doing absolutely what I wanted to do. Part of me did want to offend people a little bit, or maybe that’s not the right word.

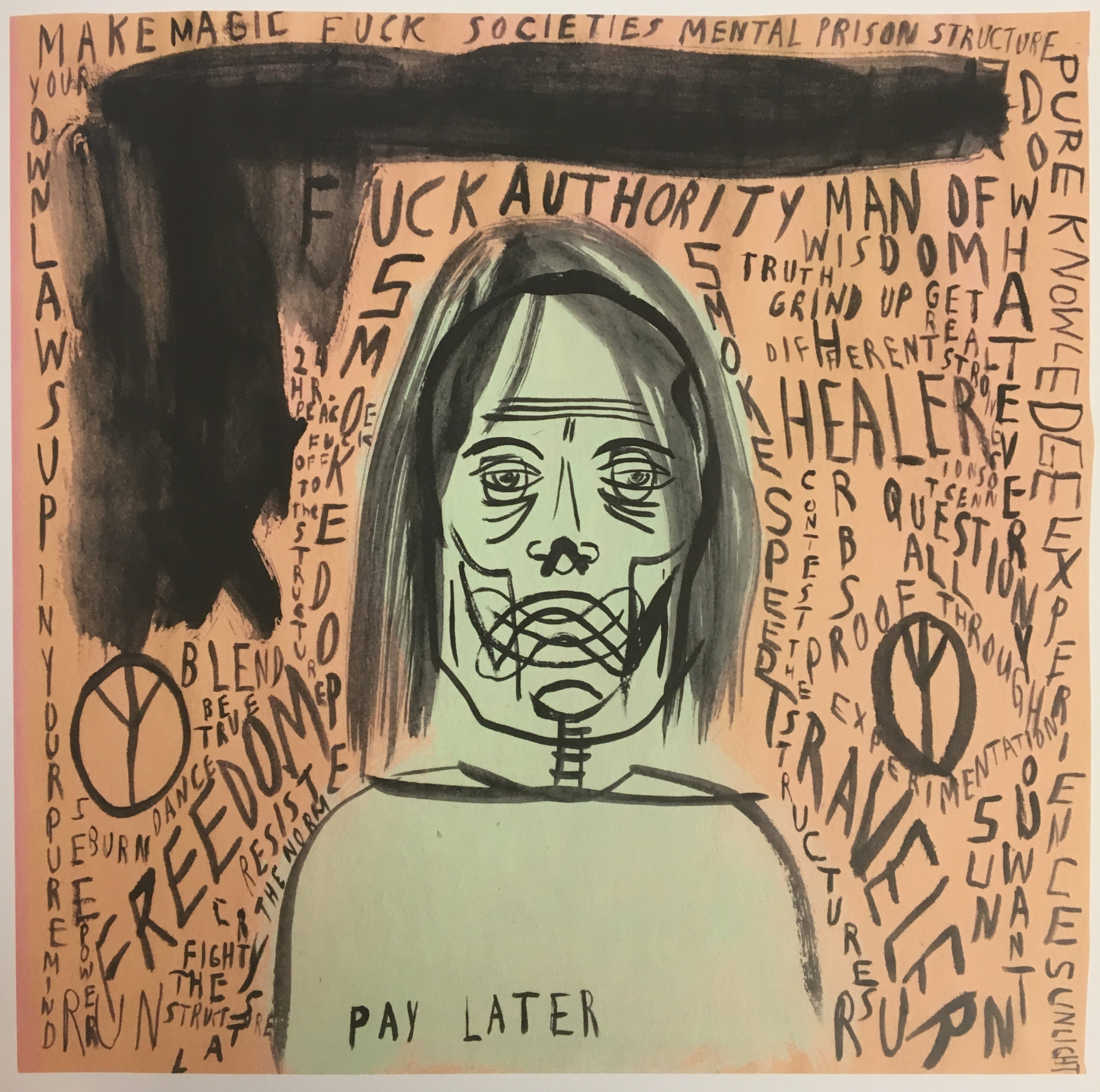

Untitled (2002)

Untitled (2002)

You wanted to fight back against the conventions that you were asked to conform to, that you couldn’t or wouldn’t conform to. To fight back with your art?

Yeah, so I was pretty happy when that guy responded in that way.

Did you know you had succeeded?

I knew that I’d succeeded at finding another piece of my puzzle of life. It gave me great, great pleasure. I mean, there were certain times when I was younger when I was trying to cause some agitation and share that. I was so angry about these particular things that I was really against because they were wrong, and I was painting about these things that I thought were really wrong. That first show that I did at Deitch had this big rainbow swastika because I was really wanting to make this space talk about problems I felt going with the perspective in America. This horrible invasion in the Middle East. This corporate government imperialism. So much loss and destruction of lives. And I had to explain that piece, I had to really explain that piece out. You have to have real reasons. I have to have a real reason if I’m going to use that symbol. Sometimes my art would get heavy and have heavy energy.

One time, I had a show at Alleged Fine Arts in New York (1998), and I did this painting that was of these stairs, and it was just a lot of stairs and some figures and stuff, but basically there was this big painting that was like six by eight feet, and it was bought by this dentist and his wife—that’s all I heard about them. But they bought this painting and they bought it for their bedroom, and they hung it up in their bedroom, and they were living with the art. They thought that was a trip. They thought it was like a really funny painting, and then they realized that it was a super heavy painting, and they brought it back. They just brought it back. They said, ‘We can’t live with this’. They were like, ‘This painting’s fucked up; we cannot have this in our lives’. Aaron gave them a credit and he never heard from them again. And now Ed and Deanna Templeton, they have it. But I thought that was pretty interesting. See, I had to make a lot of work like that, but now I’m seriously into peaceful art. That’s it. I’m only doing that from now on.

Historical Re-enactment Installation #1 (Going in a Circle) (2002)

Historical Re-enactment Installation #1 (Going in a Circle) (2002)

One of the things you mentioned about the Art of This Gallery group of works that you made with Johanna is that they were very dark, that the show confronted your positions on and feelings about American economic, immigration, and military policies and the violence these policies inflict upon people here and abroad. I think there are dark themes in a lot of your work, maybe even in all of it. I've always read this as criticality. But there's a certain way that you portray that darkness that—in my reading of it—often has a lot of compassion. There are often expressions of frustration and anger at the negative stuff in the world, but you also seem capable of expressing the flip side of that, the joy that people have the capacity to bring to the world as well.

I agree with that, about the darkness in the work. Especially when I was younger... I'm forty-four now, and I've been doing this a long time. My early work was a lot more negative, and by the time I got into making installations I started to have a more conscious relationship with what I was doing, and over the years I became aware that I was throwing some pretty heavy energy out there in these shows. There was my brain, and my brain was heavy. I started to feel like I had to have a conscious relationship with what I was putting out into the world. So I started to have to make sure that the shows were not negative. Even though I had all this negative energy in me that I had to exorcise, I had to make the shows more positive.

Untitled (1999)

Untitled (1999)

What was that imperative to make the work more positive? Did you feel that that was a way to help make change in the world, or in yourself, to put positive energy in the world and somehow make that real and manifest?

Yes, totally, that's why. When you spend all this time doing something, you're making real energy. Some might call it some kind of alchemy or magic-type thing. I kind of feel like that's what I was doing; I was making my reality through this lifestyle of these paintings, of this daily meditation of making these paintings. Cause I did it all the time. I seriously painted pretty much every day of my life when I was in my twenties and in my thirties. It's just how I kind of made it happen. When I was making these situations I thought: these are my thoughts. So I was very serious about them. And I wanted to be careful about what I was sharing, because they were real. It wasn't like I just decided to get into making this certain type of artwork that I was doing a project with and then I was going to move on to something else. It's never been like that. It's been like, actually, this is my brain.

I Am So Glad (2006)

I Am So Glad (2006)

Whatever is in your mind and in your heart at that particular moment when you're making the painting... It's like a direct translation?

Yeah. And so I started to realize that it was serious. Because if that was what I was doing, then I had to be careful and have a mature, realized relationship with it so that I could know that I was not fucking with anybody.

[related-works-module]