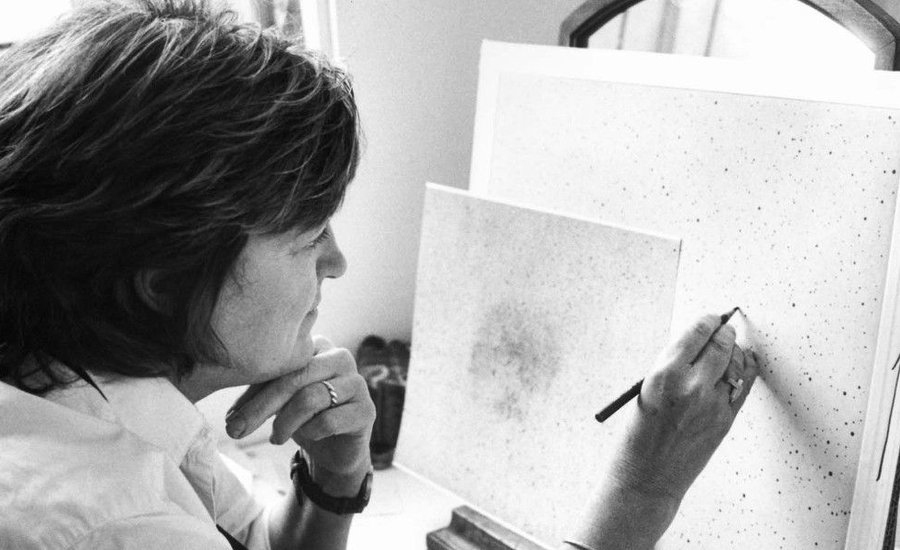

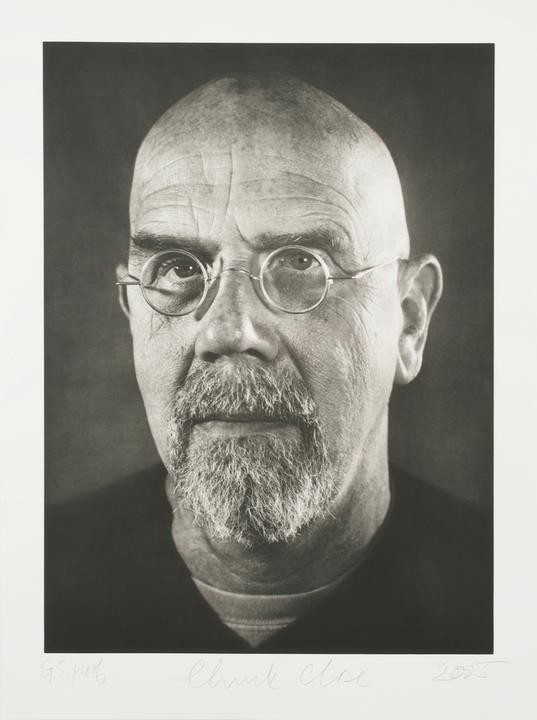

In 1991, Vija Celmins sat down with Chuck Close and had a conversation than can only be shared between two artists deeply committed to drawing. At moments, they discover uncanny similarities in their developmental timelines, at other moments, they seem as if they're ready to walk away from the conversation in frustration (Chuck Close: "I'm sorry, I feel like I've failed you. Look at her face, she'd going to ask for another interviewer!") We return to this interview, excerpted in its entirety from Phaidon 's monograph Vija Celmins , as her first exhibition of new works in seven years hangs in Matthew Marks Gallery (on view until April 22).

The artist, born in Latvia in 1938, fled the country before Nazi occupation to live in a United Nations refugee camp in Germany before relocating to Indiana in 1948. In the 1960s she became an active figure in the Los Angeles art scene where she produced pristine replicas of small things from her childhood in wartime Esslingen on a gigantic scale, such as a pencil, erasers, a comb, and a puzzle. At the time, Celmin’s trompe l’oeil paintings of wartime photographs rivaled that of Gerhard Richter’ s own “photo-painting” practice, which also dealt with war, memory, and the representation of historical trauma. So if you’re still pondering just what to make out of the fake rocks and chalkboard replicas you saw at Matthew Marks, read on to get inside the curious head of this influential artist.

...

Vija Clemins: In retrospect I have detached myself from my work somewhat. Now I can sort of see it as if I had nothing to do with it, which is perhaps one of the most interesting things that has happened as I have gotten older—that I am able to look back and say, what is this? So when I’m forced to look at imagery this way, the imagery has an intensity, especially in the early things. They have an ominous, kind of dangerous strangeness.

Chuck Close: I think those [early object paintings] are the most violent-looking paintings. What appear to be…

Benign.

That’s right. It is the most dangerous hot plate, or the most dangerous heat, or whatever, that I have ever seen. And they are scary for some reason.

Oh, I don’t know do you think so? They do have that ominous feeling that there is something going on besides just still lifes. I think that it came about because I had been painting in an Abstract Expressionist manner and I had been trying to make my strokes—the painting space—meaningful. I had tried to do passionate kinds of paintings because I was full of this energy, like I think you were, like we were when we were twenty years old. A couple of years later, I began to feel that there was no more meaning in it for me. I lost my way, I rejected it. I couldn’t resolve the stroke-making with the essential stillness of the painting. So then I went back to some basic thing, like looking at simple objects and painting them straight, trying to rediscover if there was anything that might be more authentic. But the object paintings came out sort of twisted, with more energy in them than was needed.

Vija Clemins,

Heater

, 1964

Vija Clemins,

Heater

, 1964

Do you think that we rejected Abstract Expressionism because we were coming to it so late, sort of fourth-generation junior Abstract Expressionists? We were imitating the look—it’s what we learned art looks like.

It was hard not to make it at that time.

That’s right. Do you feel that you purposefully pushed yourself into some corner where you had something more specifically personal to do?

The truth is that I have always had a lot of stops and starts in my work. So sometimes it’s hard to see a logical development. When I realized that this painting that I was doing was getting so decorative and meaningless, probably for reasons you said—that I hadn’t really originated it and received most of this information from magazines—I had to leave it. I had to back up and find a place where I felt more comfortable.

In the 1940s and 1950s art magazines were in black and white. Growing up in Seattle, I went over these magazines with magnifying glasses. As far as I was concerned, all these de Koonings and stuff were black and white. I had never seen any of the originals; I didn’t know what color they were. And it wasn’t until about 1961, when the magazine It Is came out, that I saw the first reproductions in color to see what these paintings actually looked like. Both of us have spent a lot of time making black-and-white work.

I think I probably dropped the color for other reasons.

Well, me too.

I was dissatisfied. As I remember, many people moved on from Abstract Expressionist painting—so did I. I decided to go back to looking at something outside of myself. I was also going back to what I thought was this basic, stupid painting. You know: there’s the surface, there’s me, there’s my hand, there’s my eye, I paint. I don’t embellish anymore, I don’t compromise, and I don’t jazz up the color.

One of the things that I remember being very struck by was an Ad Reinhardt article. I think it came out in 1957, in ARTnews or something. Remember that article on twelve things not to do? I’m just going to read the very first one because I believe that I had never seen Reinhardt’s work, and I don’t think I’ve ever been influenced by his painting, but I have been influenced by his writing. He wrote twelve technical rules, or how to achieve the twelve things to avoid—I loved that. No texture, no brushwork or calligraphy, no sketching or drawing. Now you see I drew but I didn’t sketch. What I finally did was to leave painting: forms, design, color, and, I thought, invention.

I remember discussing this article in Indiana, of all places, in this very traditional studio where older students had their own little, messy workspaces. I remember being inspired to imagine what is art if you remove all these things. What was left was a kind of poetic reminder of how little a work of art really is art, and how elusive it is to chase the part that excites you and turns one thing into something else. And how tiny that part is, and how hard it is to define. So I was inspired to throw away as much as I could.

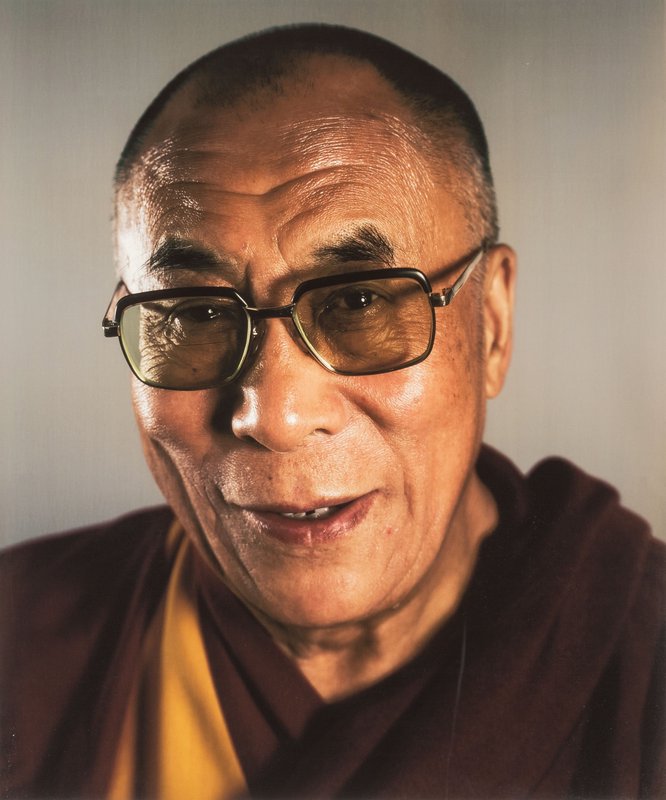

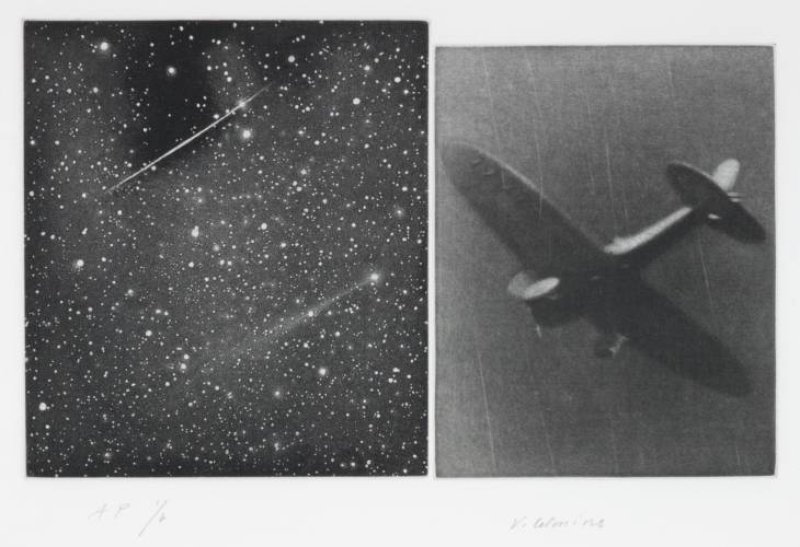

Vija Celmins,

Plane

, 1968

Vija Celmins,

Plane

, 1968

Actually, we were on opposite coasts purging our work.

Did you do that too?

Absolutely, sever self-imposed limitations: I am not going to do this. I can't do that. I am not going to use this material. Get color out of there.

Were your first things black and white?

Yeah, I didn't work in color for several years.

There were a lot of changes going on in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Johns , Warhol , Rauschenberg , Morley ... all those people that started doing dumb objects, dumb panting, commercial-art painting, whatever you call it. I began to look at Morandi, too, because he was showing up in magazines.

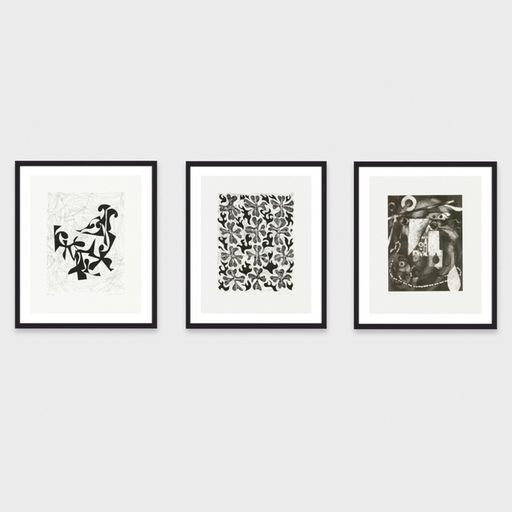

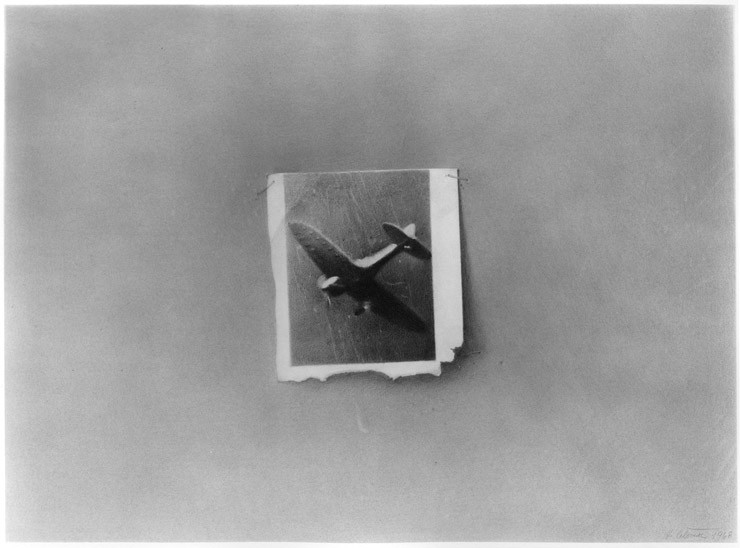

Vija Celmins,

Spider Web

, 2009. Available on Artspace for $7,500 or as low as $660/month

Vija Celmins,

Spider Web

, 2009. Available on Artspace for $7,500 or as low as $660/month

As much as your work is purged of a lot—trying to get the handwriting out of there, trying to get the brushwork out of there, get the color out of there, and all that stuff—it is amazingly physical. There is a tremendous amount of physicality to it. It is not just ethereal. I think that is one of the dichotomies that is really riveting and so engaging in the work. At once they look like they just happened and yet there’s this physicality. The drawings are incredibly physical as well.

Sometimes I’m convinced that there is nothing else but the physical art of making the art. Sometimes I refine it too much which makes it seem ethereal, which of course it’s not.

You’re talking about how conceptual drawing with graphite is. There isn’t so much there, just decisions, just a record of decisions having been made.

That’s because I see drawing as thinking, as evidence of thinking, evidence of going from one place to another. One draws to define one thing from another. Draws proportions, adjusts scale. It is impossible to paint without drawing. I see the drawing in your painting, too.

Going back to the object paintings I started in 1963-64, I dropped the scale and composition altogether and painted the objects one by one, life-sized: hot plate, lamps, refrigerator, radio…I made some of the objects three-dimensional like the Comb . I think of them as having fallen out of the picture plane. They are not really sculpture.

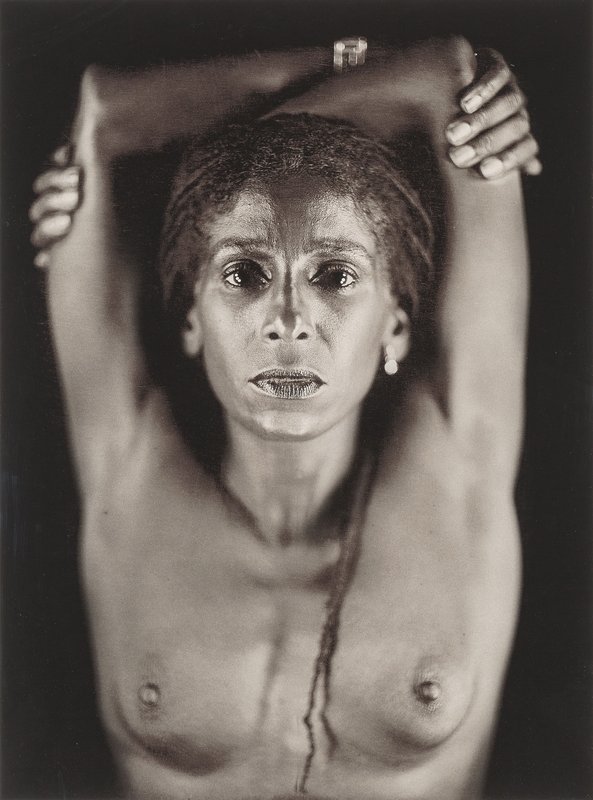

Vija Clelmin's posing next to

Comb

(1970)

Vija Clelmin's posing next to

Comb

(1970)

I don’t think of your sculpture as sculpture, but more like painting that comes out of the room and occupies the space with us.

That’s a nice way to put it. I was grappling with what it meant to work on a two-dimensional plane, and come out of it and go back into it.

I think all this has a lot to do with artifice and the artificial. In a sense you are decorating a surface with painting, but then there is the desire to actually paint around something. It makes me think of your choice of photographs because you say in your notebook, “ My eyes were honed in nature. I practiced seeing the desert.” Some people think that you’re not looking if you’re looking at a photograph.

Oh, that’s ridiculous.

Why do you put this artificial layer between you and what you’re looking at?

The photo is an alternative subject, another layer that creates distance. And distance creates an opportunity to view the work more slowly and to explore your relationship to it. I treat the photograph as an object, an object to scan. Actually, the first time I used photographs was really because I had been away from my family and was lonely. I had been going through bookstores finding war books and tearing out little clippings of airplanes, bombed out places—nostalgic images. At first I painted them, later I decided the clippings were this wonderful range of grays for me to explore with graphite. Then I started to do these moon drawings from photographs taken by a machine that had recorded the range of grays on the moon and had transmitted them back. Then they had been photographed and printed in a book, and then…

There was layering in between.

I thought of it as putting the images that I found in books and magazines back in the real world—in real time. Because when you look at the work you confront the here and now. It’s right there.

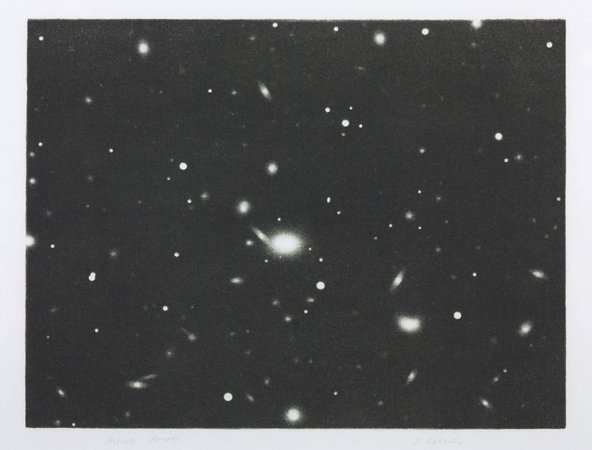

Vija Celmins,

Galaxy

, 1975

Vija Celmins,

Galaxy

, 1975

So you approach these photographs as an object in the same way as the lamp had been an object?

Right, I did at first. I think you can see that the whole idea at first was that it might be possible to put something in a two-dimensional plane, or on it, or somehow solve that problem. You can see that the photographs have the same kind of single-object imagery, like the objects that I had been painting earlier. In a way, the photograph helps unite the object with the two-dimensional plane. Although I think that with airplanes there is a kind of wonderful place where they really float, and then they become dimensional, and they take off as well as staying flat. I did not realize it then, but now I can see that the subject matter has a kind of internal tension that also exists in the work. The paintings tend to have an internal feeling, as if there was something behind what you see.

The paintings are very lush and, at the same time, they're incredibly restrictive. That is a funny dichotomy.

I'm always aware of the limits of painting, and have come to think that the limits are what give it more meaning. Of course, one has to find the limits. I painted so much between 1961 and 1964 that I probably went through five lifetimes of different sorts of painting: Matisse , Hoffman, Gorky, and de Kooning . I think you can also see quite a bit of a Morandi influence, as well.

More in the early color work. It's a world of color but it's really approached monochromatically. Later, when you get color totally out of the picture, the viewer fills in the color in his/her mind. I always thought that black-and-white photographs of war, for instance, were far more scary that color photographs of war because color photographs of war always look wrong—the blood doesn't look like blood, it looks like ketchup or something. But in a black-and-white photograph of war you fill in the color in your mind and make blood blood-colored. In a way, it's sort of less artificial. By purging the work of color it actually makes them more naturalistic.

Yeah, but naturally I didn't think of that either. What I know is that I didn't just wake up one day and say, I'm not going to use color. I slipped into it through drawing the photographs, which were black and white, because those were the only photographs available at the time. The second thing is that I do believe I wanted a more sombre not and I thought that color was an extra, as if I were decorating something.

Vija Celmins,

Big Sea II

, 1969

Vija Celmins,

Big Sea II

, 1969

I understand that. I got rid of color because I felt I depended too much on it. I'd been told that I had a good sense of color and all that. It just occurred to me that the color I was using was learned color, was art color, it had something to do with other people's paintings. I could see wanting to get it out because it was reminiscent of a certain kind of art.

That's right, though I often think that my thing of removing things was going too fast. Part of it was an intellectual series of decisions to remove stuff arrived at intuitively. Then I think it may just be my nature to throw stuff away.

Let's talk about your nature. At one time, you described yourself as lazy. To look at your work, the last word to describe you as is lazy. When we started talking about compulsion you said that everyone would assume you're a very compulsive person. I don't think you're a very compulsive person, nor do I think I am. A compulsive person is driven to do things whether they want to do them or not. They have almost no control over themselves.

Oh no, I'm not like that.

I don't see you that way at all. I see that you force yourself to behave in a compulsive manner, that is, to sit there and keep doing it. But it doesn't come from some kind of compulsive drive.

No, I don't think it's mindless compulsion.

Do you think that people like your work for the wrong reasons?

Who knows why people like work. At a certain point, you're very happy that people look at it at all; in that way it's good. My feeling is, however, that often people only look at the image. I feel that the image is just a sort of armature on which I hang my marks and make my art. The early imagery, especially the war things, had a more specific emotional tension, but most of my later imagery developed without choosing any specific kind of symbolic meaning. I don't use the ocean in any kind of symbolic way. These first broken-surface images were a way to articulate the surface of the drawing in a Cubist way: with individual marks that break up the surface and then build up into a whole.

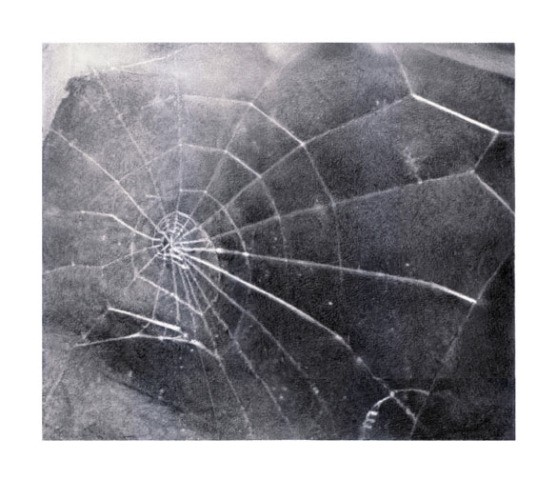

Vija Celmins,

Concentric Bearings B

, 1984 is available on Artspace

Vija Celmins,

Concentric Bearings B

, 1984 is available on Artspace

In your notebook you talk about building a painting: 'I build the work like a house, like a construction. Hah, all the materials pull together—When I was young I had a mechanical ability.' You could build whatever you wanted. I like to think the way I work is almost like knitting a painting, or something like that. I don't think of it as painting in layers, the way you talk about finding a way to get down to an armature for the individual marks to build upon. That's something that interests me a great deal.

I have long been interested in building a form in the painting. It's hard to define the word form, but I wanted to make a work that was multidimensional and that went back and forth in space yet remained what it was: a small, concentrated area that was essentially flat. Who knows why you want to do this. So, in a way, I thought of painting as building a dense and multi-leveled structure. Now I tend to think of it only in physical terms, but you could say that it alludes to a denser experience of life. You have to re-imagine it in other terms, which is lead [graphite], paper, paint, and canvas. My feeling is that we all do essentially the same thing. I like to talk about it in terms of structuring because when I'm working, my instinct is to try to build and to fill. To fill something until it is really full.

The last time we were together we were talking about how important the Abstract Expressionists had been for us—how we thought we learned from de Kooning, what we thought we learned from them. Now, most people looking at your work would not assume these people had played any seminal role in your deciding to make the kind of work that you make. Yet I see it as absolutely integral to what you do.

Good, because I do too.

Whether it's the all-overness of the American painting: doing away with foreground, middle distance, background, and making the whole surface...

Right, although, I don't think that started with Abstract Expressionists. Another artist I look at carefully is Cézanne. Cézanne recognized and gave value to the space that is in front of you, here and now. It is not just an illustration of absent events, he did it self-consciously. The mark was a mark on the mountain; and that mark also indicated that atmosphere in which the mountain existed; and, finally, it is also a mark on the canvas. At a certain point I realized that this work, which can only allude to so much outside of itself, nevertheless remains comprehensible only through the organization of that flat arena. This is no limitation but an essential expressive element of painting. I think that the abstract expressionists, certainly de Kooning, knew that and used it. They added another subject, however, which was the unconscious—but, of course that's the subject you like to keep bringing up.

I'm sorry, I'm the last person in the world to keep bringing this stuff up. I feel like I've really failed you. I hate it when people ask who my subjects are looking at, and what they are thinking, and who are these people. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There is a transcendent quality to your work and to all great art.

What do you mean by transcendent?

It's the magic of art that makes graphite more than just graphite. Look at her face, she'd going to ask for another interviewer! I don't see anything corny in that.

So look at your work, maybe that's the nature of art. You do one thing and then something else always comes through.

You stack up the bricks, and you build something that is more than just a pile of bricks. That’s what you’re doing; the approach is bricklaying. It is something that I respond to in your work.

I would say that the work, beginning with the ocean drawings, is more like that. It really went into kind of rigorous building, and letting the material be the material. Letting the image be more and more like an armature. In some of these the image is almost nothing. It just holds you and it articulates the picture all over. See, I’m really interested in that. For some reason I’m able to do that over and over again without getting bored.

Vija Celmins,

House #2

, 1965

Vija Celmins,

House #2

, 1965

The last time we were together we were talking about how important the Abstract Expressionists had been for us—how we thought we learned from de Kooning, what we thought we learned from them. Now, most people looking at your work would not assume these people had played any seminal role in your deciding to make the kind of work that you make. Yet I see it as absolutely integral to what you do.

Good, because I do too.

Whether it's the all-overness of the American painting: doing away with foreground, middle distance, background, and making the whole surface...

Right, although, I don't think that started with Abstract Expressionists. Another artist I look at carefully is Cézanne. Cézanne recognized and gave value to the space that is in front of you, here and now. It is not just an illustration of absent events, he did it self-consciously. The mark was a mark on the mountain; and that mark also indicated that atmosphere in which the mountain existed; and, finally, it is also a mark on the canvas. At a certain point I realized that this work, which can only allude to so much outside of itself, nevertheless remains comprehensible only through the organization of that flat arena. This is no limitation but an essential expressive element of painting. I think that the abstract expressionists, certainly de Kooning, knew that and used it. They added another subject, however, which was the unconscious—but, of course that's the subject you like to keep bringing up.

I'm sorry, I'm the last person in the world to keep bringing this stuff up. I feel like I've really failed you. I hate it when people ask who my subjects are looking at, and what they are thinking, and who are these people. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There is a transcendent quality to your work and to all great art.

What do you mean by transcendent?

It's the magic of art that makes graphite more than just graphite. Look at her face, she'd going to ask for another interviewer! I don't see anything corny in that.

So look at your work, maybe that's the nature of art. You do one thing and then something else always comes through.

You stack up the bricks, and you build something that is more than just a pile of bricks. That’s what you’re doing; the approach is bricklaying. It is something that I respond to in your work.

I would say that the work, beginning with the ocean drawings, is more like that. It really went into kind of rigorous building, and letting the material be the material. Letting the image be more and more like an armature. In some of these the image is almost nothing. It just holds you and it articulates the picture all over. See, I’m really interested in that. For some reason I’m able to do that over and over again without getting bored.

Vija Clelmins,

Two Stones

, 1977/2014-16. Photo: Matthew Marks Gallery.

Vija Clelmins,

Two Stones

, 1977/2014-16. Photo: Matthew Marks Gallery.

[related-works-module]

RELATED ARTICLES: