From painting and sculpture to design and architecture, the Cuban-American artist Jorge Pardo uses the tools at hand to challenge the notion of the artist’s role, dissecting the system in which he himself exists and sparking sometimes-fierce debate along the way. In many ways, his medium is unfamiliarity, as evidenced by his ability to operate in the art world as a perpetual outsider.

In this interview from Phaidon'sJorge Pardo, Pardo talks to the critic and author Lane Relyea about how he's found his own way in the strange world of art.

Lane Relyea: You were born in Cuba, so you come from not only a different culture but a completely different political and economic system.

Jorge Pardo: I’ve always considered myself a post-Marxist. I don’t believe in any of that shit. But at the same time I’m aware of the consequences of that kind of collapse. It’s not something incidental or foreign to me.

When you left you were six.

Yeah, my dad was the first-born of Hispanic parents. We didn’t have a particularly deep connection to Cuba. A lot of the people who left had very short histories with the island. It was a very transient place. Cubans didn’t feel indigenous, they didn’t feel Spanish, and they certainly didn’t feel American. It was this kind of odd-ball identity. When Castro came into power my parents were protesting like everyone else in their class. But by 1965 it was becoming clear that any kind of mobility they’d had access to was completely eroded.

So you grew up in Chicago, then moved to Los Angeles to go to college.

While I felt comfortable in Chicago as a working-class city, I never felt particularly connected there, outside of my friends. I’d grown up in this Cuban enclave, but almost everyone had already gotten married or left for Miami. I was the odd man out. And I had always done a little better in school than the rest. I didn’t feel comfortable going to work at my dad’s factory and ending up like he did, as a supervisor. At school I found something I was interested in. Then one of my teachers told me, “You should move to California. That’s where all the good schools are.” But I didn’t know enough at the time to tell which schools were the good ones.

So not only do you take off while still an undergraduate, but you end up at Art Center, a private art school.

That was the weirdest thing, hanging out with the rich kids. It was my confrontation with this class—they didn’t have to pay for their own school, they got to go to really fun places in the summer, their parents would show up in fancy cars. Art Center still didn’t really have an art program yet. There were only three or four fine arts students at the place. A lot of people don’t realize that I’m a generation before a lot of what happened in L.A. I just started really young. I was already at Art Center in 1983. I finished in 1987.

By 1987 you were already active with what would become the exhibition space Bliss in Pasadena. That was in the heyday of postmodernism.

But I never connected with any of it. It seemed like a really New York culture. I didn’t understand it until Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, Stephen Prina, and Mike Kelley came to Art Center. Then I learned that there was this slingshot effect that would happen vis-à-vis California artists bringing their students to New York.

But the art market was in the toilet at that time. Maybe that’s why a lot of L.A. artists chose not to go to New York immediately after graduation. I associate you with that generation.

The first one who didn’t leave was Mike Kelley. But by the time I got out of school there was really no reason to go to New York. It was the end of the relevance of things like the journal October. The discourse in L.A. was much more interesting.

In the early 1990s, when I started working at CalArts, the place was still very much locked into a Frankfurt School discourse, and identity politics was at its peak. A really prosecutorial critique dominated.

When I got out of school everybody was responding to theory, institutional critique, and so on. They were trying to see what was left. But I never believed any of it. For me, there were too many contradictions in that model. I had tons of problems with Michael Asher because I didn’t believe that rich people should start communes, which in the end was what he was doing in his class. I’m being facetious, of course, but really, if you’re talking about art having a political output, it can’t fail without consequences. The projects that I’ve tried to define for myself are ones that would allow me to see that, to reinforce that. So I went back to people like Robert Smithson who were locating their problematic within other places and sites. It made a lot more sense to me.

There’s also a lot of displacement in Smithson’s work.

Right. I was interested in Smithson because his model of presentation didn’t really see incompleteness as a lack but rather as a productive space, and as something inherent. Things really opened up once I started to think about it that way. I no longer had to think about the exhibition space as the threshold and the frame but rather as part of a larger circuitry of things.

So instead of focusing on the art institution, like in Asher’s work, you turned to a more expansive field of locations and conditions. There was a big change in the institutional landscape of the art world that your generation ushered in. I’m thinking of the mid-1980s and the Republican Party’s efforts to abolish the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts). Among artists there were a lot of mixed feelings about nonprofit arts spaces, ranging from indifference to resentment over who was getting money and why. In L.A. the important artist’s space was LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions). It had a multi-million-dollar annual budget. Then by the end of the ’80s its funding evaporated, and it imploded. But already young artists had begun looking elsewhere, and all these do-it-yourself apartment galleries were cropping up, like Bliss, that were much more short-term, flexible, and entrepreneurial, much more befitting the New Economy.

Again, there was a lag between what we were doing at Bliss and the appearance of these other spaces around 1992. The later spaces reflect how in the 1990s graduate art students became much more organized, and the level of ambition and the projection of professionalism was amplified. Bliss was something else. It was a very casual undertaking. In 1987 we decided to do a show because we thought the graduate shows around town were kind of stupid, too serious. So we thought, “Why not do a community show?”

We invited our friends and also went door to door, got to know our neighbors. We said, “We’re doing this art show. We’d like you to put something in it. If you’re an artist you can show art, but you can also choose something else that has enough value that it seems worthy of that kind of presentation.” We got all sorts of crazy shit. We got some dead woman’s paintings from her husband, still life set-ups with bottles and, like, a dirty sock. Bliss was a way of doing an exhibition on the run. The impetus was, “Here are these artists making their work in a bubble. Let’s put this stuff next to some real stuff, see what it does.”

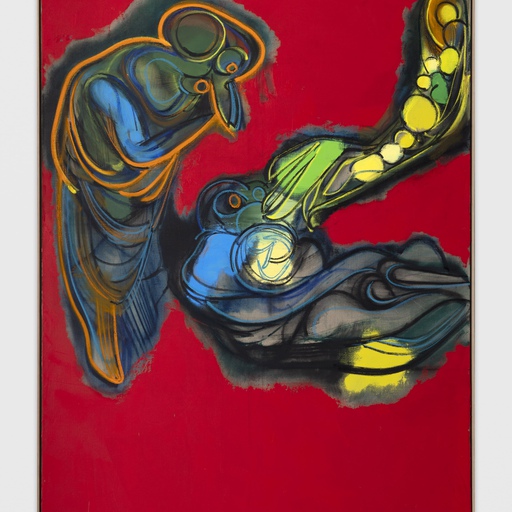

Untitled (2), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Untitled (2), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

It sounds like your work is driven by a lot of skepticism, the skepticism you have toward the value of art and the value of artists.

I’ve always been very skeptical about what an artist actually is—not that it’s bad or anything. To be honest I’m kind of dumbfounded most of the time. Bliss was consistent with this interest I’ve always had in setting up situations where I could start to understand the things that work, what the value of particular gestures are. I think the skepticism started for me because the process of becoming an artist had to do with entering a different class.

Which goes back to your attending Art Center with these kids who were for the most part from privileged backgrounds.

Yeah, or even if they weren’t from privileged backgrounds they had been on this track of being an artist for quite a while. They had taken a lot of art in high school, and their perception of themselves as artists was a lot more stable than mine. I just kind of parachuted into the whole thing. It was something that I didn’t really quite understand in relation to the upbringing I had. And to be honest that was part of the attraction of it—there was a kind of foreignness to it. Art was this thing where you could sort of reinvent yourself and at the same time reinvent what an art methodology might be. And if that’s the case then there is always some skepticism—which is just another way of saying that part of what makes art interesting is that every generation gets to take skepticism redirecting its consequence in relationship to what else is happening in the world. And it just seemed to me that some of the pedagogical methodologies back then weren’t really taking advantage of that.

Like institutional critique and so on. But still, back then people like Michael Asher and Barbara Kruger were much more of a presence. Nowadays you look around and the dominant models aren’t those people. It’s something closer to you.

I am one of the models, but how I’m used as a model in the art world doesn’t correspond much to what I actually do. I don’t teach, for example. I don’t play the game of reifying myself, like some of my colleagues do. I make more work than anybody because I don’t want to be bored. For someone who is as well known as I am, I’m not that expensive. I’m perceived as somebody who works from a position that’s marginal to art, but I don’t think of myself that way.

I’m an artist, I work with dealers, I make a living. I’m someone who’s very much in the art world, but if you look at the spread of projects I’m working on, I’m very much all over the place. And I don’t have a problem with that. I’m not interested in representational painting, or non-representational painting for that matter, and I’m someone who’s well versed in formalism—I know the game. I know what’s at stake in that kind of gesture. It wasn’t interesting to me 20 years ago, and it’s not going to be interesting to me now. I’m interested in finding a way to understand the value of what I do.

So operating at once inside and outside the art world is how you answer your skepticism about the value of art.

Yeah, absolutely. When I was still at Art Center, or just shortly after, I was approached by Tom Solomon. He wanted to exhibit a group of works that I had received a lot of attention for in school, but I refused the show because I wasn’t sure that these works could be made outside of school. And I really wanted to understand whether what I was doing, what I was becoming, was something that would sustain my life, that it wasn’t just an academic pursuit. It seemed to me that the way one is trained to be a painter or sculptor didn’t really allow for looking at one’s life in a very comprehensive way. If you wanted to be a painter you would find a sliver of that tradition that you would intensify, and you’d spent the rest of your life doing it. And that didn’t seem very interesting. It didn’t allow for the kind of latitude that I was interested in. You couldn’t operate with a lack of focus. So I waited two and a half years to make a new body of work, and that was what I eventually ended up showing with Tom.

Looking back at the stuff you made at Art Center, I was struck by how involved it is in photography.

I was working with Prina at that time, and I was trying to understand a post-subjective theoretical moment. I would take a cup and paint the inside black and stick a hole in it, then insert a piece of film and place it in front of a mirror so that the cup would take a picture of itself. In one work I put the cup in the men’s bathroom. It was like a six-minute exposure. What that did was render any discussion of what the picture looked like utterly ridiculous. I felt like I had come up with a way to talk about what was really in the picture. I had been weaned on all this photography discourse—identity, Victor Burgin. I really wanted to blow it up to see what it was. I guess my point was that photography is a witness to nothing.

And then your first solo show outside of school was the one with Thomas Solomon in 1990. It seems that you could characterize the work in that show as having two opposing aspects to it. On the one hand there were these everyday items, just an ordinary ladder from the corner hardware store or just a wood pallet, but you’d taken them apart and redone them, remaking parts out of different kinds of woods. And there was something very self-referential about that. It made the objects appear to be questioning their own status or identity. It’s a kind of self-referentiality that seems familiar to a certain idea of art. But that self-referential model is very different from the readymade model, the idea of shifting focus from the object to its context or conditions, and also different from the idea of integrating art and life. In one sense you had the objects that circled around on themselves, and in another sense the work seemed very outward oriented, about context and expanding the boundaries of art and so on.

The works use different points of view to output reflexivity. At the time I was trying to map out how the spaces in which I located myself had changed. As a student I think you really make pieces that reflect the dominant methodology within the school, within the group that you are in, your fellow students and your professors. I’d worked with painting, photography, and more or less the visual aspects of sculpture. What I was interested in was taking certain reflexive components within those practices and applying them to things around me to describe to myself what I was, what my interests were. I wasn’t thinking about making pieces for exhibition anymore. I was teaching myself how to work with these materials, how to work with wood. Most of the things that I used for that show were things I found pretty close to where I was living at the time.

But the work very pointedly raises the question of value. Like with the ladder piece, where you alter this ordinary object to incorporate kinds of wood that signify as exotic and valuable within certain contexts. You would have to be a connoisseur of woods to know that African bubinga is a great wood.

But there were other kinds of wood, too. There was redwood, which is local, and on the top of the ladder there was a piece of particle board. So the different interventions into the ladder had different class values. It was using an object to reappropriate a value study of itself.

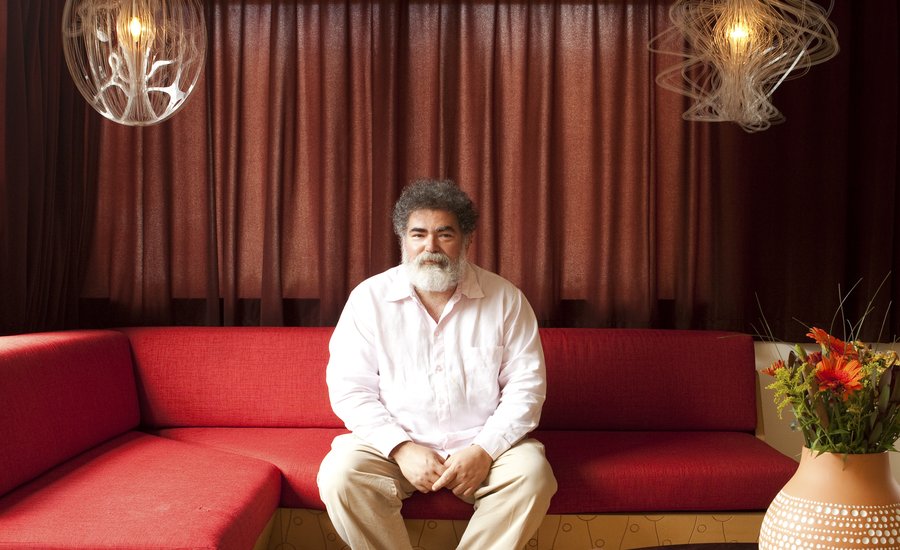

Untitled, 2016 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Untitled, 2016 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Then the next show you had was in 1991 at Luhring Augustine Hetzler in Santa Monica.

That was a real turning point because my shows became about smaller issues. They became a little more focused. The Luhring Augustine show on some level wasn’t really different from the Solomon show, but it used spatial ideas as opposed to object ideas. One piece at Luhring Augustine that I thought was more successful was called My Mom’s Soffit. It was just basically the soffit of the kitchen in the apartment where my mom and dad were living at the time. I just took it and redeployed it on the ceiling of the gallery. It was the beginning of my understanding of how to deploy reflexive art strategies in environmental or contextual scenarios.

Why did you want the relationships you were setting up to become more architectural rather than grounded within some object-identity?

You can’t avoid returning to a very specific type of formalism with the objects, which I found limiting. My interest at the time was how to put these kinds of questions into the world, how to do it in a space that was also connected to the outside.

That show also ventured into the art world. There were references made to the collector Robert Rowan and works that incorporated pages from a J. Crew catalogue.

The J. Crew catalogue with Matthew Barney in it as a model. I had some friends who were going to Yale and knew Matthew, and we all met. It was already clear even within the university that he was somebody being prepped to ascend within the art world. That seemed interesting to me, that you could deploy this history in advance. I knew that he was having a show at Stuart Regen a couple of weeks after my show opened, and I thought it would be interesting to try to set up a critical relationship between the two.

And one of your pieces at Luhring Augustine used an essay from Arts Magazine in which Jerry Saltz champions Barney even before his first gallery show. I remember how stung I felt by that particular piece because I had just been contacted by Artforum to write an “Openings” review on Barney at Stuart Regen, and I felt like I had been enlisted to help in that ascendance.

It seemed to usher in a new era in terms of the marketing of an artist.

But the other interesting thing about your use of the J. Crew catalogue, at least in hindsight, is that it seemed to hold out J. Crew itself, the clothing line or marketing system, as a model of relational objects. There was a storage system, or I should say a system of display cases, that you put up against the window of the gallery.

At the time my friend George Porcari, who’s also an artist, was buying everything from J. Crew. Not as art or anything, just because he liked the outfits. So I put George’s clothes in there. But I was trying to look at how J. Crew was selling lifestyles, not necessarily clothes. It was one of the first instances that I remember of marketing being dealt with in that way. Obviously the comparison I was asking the viewer to make was between that and what was happening around Barney.

I think it was a year later, in 1992, when IKEA was considering whether to close its U.S. operations because sales were so low here, and instead they decided to change their strategy, somewhat along the lines of J. Crew. And suddenly they became a huge success. Part of the change was not just to sell designed objects so much as to sell cheap and disposable design, and to encourage the idea that one doesn’t hold on forever to a sofa or other things that used to be thought of as durable goods, that one could throw these things away. Disposability meant that you could incorporate more and more of your object universe into lifestyle, that more objects could conform to these consumer patterns that have to do with constant fashion make-overs.

Yeah, and stuff starts to get cheap. A lot of it is being made in Asia for the first time.

So the comparison you draw in the Luhring Augustine show is between, on the one hand, the marketing of consumer objects as no longer isolated identities but as part of a kind of expanded field of lifestyle and, on the other hand, the circulation of artworks and artists within a kind of expanded field that has to do with marketing, criticism and so on. And that seems to herald a more general shift in the art world. Jeff Koons and art about spectacle goes out of style around then, and instead you get the beginnings of what Nicolas Bourriaud calls “relational aesthetics.” You get a lot more DIY stuff, you get interest in the body, slacker art, things like that. Art goes much more towards additive sculpture rather than glossy commodities behind glass or on pedestals. Instead of looking at one thing, people are looking at networks of things and thinking about additiveness as a new kind of value.

I just think there is less to ask of the work at a certain point. The whole question of its autonomy is thrown out the window. When it comes to my own work, I don’t think about it in terms of autonomy. I think of the work primarily as discursive. By doing that, you have to debase its inherent value as an object. In other words, how it’s owned and by whom are not as significant as how the work is made present. Whereas I think the generation before me, the Michael Asher generation, still believed that the most discordant aberration that can befall an artwork is that it doesn’t reach certain classes because it is being collected by the elite.

Untitled (4), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Untitled (4), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Can you give an example that illustrates how your work is discursive?

The house on Sea View Lane (4166 Sea View Lane, 1998), which was done as part of the L.A. MOCA show. That project starts as a scam. Its operative discursive mode is hearsay. Most artists would think that’s horrible, but I’m saying, “Wait a minute, let’s really look at hearsay.” I knew this project was going to generate a lot of it because it was an oddball project. Not that I’m a con-artist or something, but I wanted to make an object that would resist a certain critical formalization. I wanted to make a work that would impose a lot of different critical modes. Everything from other artists saying, “Oh you got a free house,” to the museum-goers who would visit on Sundays when the show was up and would say why they wouldn’t like living here, that when they wash the dishes they really need a window, and this house doesn’t have one.

It was really interesting to make this object that could collect all these points of view that were beyond my ability to forecast. That’s my process—I’ve always thought that making an object that can enter the public sphere would be much more productive than framing it within a gallery. There’s an unmanageability when you do things in the world. You really are confronted by social conditions that don’t necessarily conform to the models that you’ve grown up learning to master.

In so far as the house seems to curl in and look at itself, it recalls those early works where you make objects into pinhole cameras that can produce self-portraits.

I was interested in how that type of house has an inherently reflexive component. Basically the house is just a courtyard. It’s this object that shapes itself up and down according to the hillside and at the same time visually gives no access from the inside to the outside. The only way to look out is to look at some other part of the house. And yet this is how the house reverberated out into the rest of the neighborhood. It was raised as an issue at the community review, which is a public hearing for the seven people on either side and in front of your lot. You show them your design and they have the right to say yea or nay. At the time, I didn’t even know that neighbors could say anything about building a house. It just seemed like a large enough project, larger than my ability to forecast all of these contingencies. And the big problem the neighbors had with that particular design was that it didn’t have any fenestration in the front.

You’re antisocial, Jorge.

No, not at all. I’m very social. A lot of people come over. We have a lot of fun at my house. Even my neighbors now, they like me.

Now that the museum buses have stopped rolling through every Sunday.

I didn’t really understand why you needed to have a front yard. If you live on a hillside in L.A., the lots aren’t big. Why then do you want to give 30 percent of it away to some guy driving by? It’s ridiculous.

To what degree was the actual design, even the materials of the house discursive or historicized? To what degree were you starting with ideas that had to do with your knowledge of architectural history, southern California architecture, modernist architecture?

For one thing, it’s just a wall. It’s based on an Arab house, one that first got disseminated through Spain, then the New World and Latin America. But in this particular case it’s torqued as it goes down the hill. It aspires to privacy, but in order to do that it has to contort itself. I could have very easily designed a kind of knock-off of a Case Study House. That’s a really simple thing to do—you make your wall of glass, it’s not a big deal.

I was interested in bringing in that tradition but at the same time making the type of spaces that I was comfortable living in, addressing the particular areas of the property in terms of the slopes and the views and the kind of privacy I wanted. But also I was looking at a lot of architecture. I probably spent half of the 1990s really looking at architecture and thinking about what architecture meant to me and in terms of living in L.A. And what I wanted was to make the house at odds to some degree with the postwar Case Study ideology of utopianism. This wasn’t a machine that could easily organize and contain the type of social problems that we were living with in the 1990s. The house is strange. It uses materials that you find within the tradition of architecture in Los Angeles but really more phenomenologically than ideologically.

So beside Smithson, your work also strongly recalls this other moment, about twenty years earlier, which is not about displacement and dispersal but about unity, that moment that includes the Case Study Houses, the MoMA “Good Design” shows, this dream of what Clement Greenberg around 1950 called “a period style” in the U.S. that would bring together International Style architecture and modern design and avant-garde painting and sculpture all within an everyday, middle-class,managerial, material culture.

I always read that moment as a leapfrogging of German Romanticism into the 1950s. In other words, if after World War II the culture enters a post-traumatic period, it’s not enough to deploy this rigorous aestheticization within very limited parameters. There’s this cubist-derived style, but you could also look at the 1950s in terms of technology, in terms of the Cold War—it’s the simultaneity of these things that interests me. I’m not one of these artists who makes everything so clear it means nothing. I’m interested in how architecture can address aesthetic issues in a way that is sloppy. I think architecture can accomplish a kind of dissonance, not this perfect configuration but rather an unraveling.

But it’s hard to not raise the expectation of some grand utopian conciliation when you have this marrying of utility and aesthetics in your work.

I always thought that that expectation was spent in the 1950s. It’s a bad model. International Style architecture is the only architecture that aspires to that Wagnerian bullshit. Nobody talks about how, for instance, Walter Gropius in the U.S. translates into Cabrini Green and the Pan Am building. If we’re talking about poetics, then poetics don’t really thrive in that culture. They thrive in places where a lot of odd things happen.

I don’t know if I or anyone else would argue that the agreement between utility and the aesthetic would be exclusive of poetics. More likely it would be exactly such an agreement that would produce the poetic. That’s the utopian promise of the merging of art and life, that it would bring about an expansion of the realm of the poetic. But it seems like you’re very deliberate in your work to produce a lack of agreement and conciliation, by making sure the work gets read against itself so that it will always be seen as at once an artwork and not an artwork, as a public venture that’s also a private object.

Or an entrepreneurial venture. All these things get very muddled.

It’s like a motif in your reception—people want to take your work as being utopian and as encouraging a fusion of art and life, and then they get befuddled when you do things like put a cigarette machine on the pier you built in Münster (Pier, 1997), or have a house that turns its back on its neighbors. And you’ll even do things that go well beyond creating dissonance to just being inscrutable and opaque. You’ll make reference to things that are so particular they can’t be translated or generalized. For instance, for the catalogue that accompanied the MOCA show you included a section that just listed names of people, some names that people in the art world would likely recognize, like Jim Isermann, but also names of your family members and some names I have no idea where they’re from.

One was the name of my pillow when I was a little kid. But why not introduce that kind of information?

Untitled (5), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Untitled (5), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

How are people supposed to deal with it, other than to give up on the whole discursive process, on any hope of interpretation, discussion, dialogue, and so on?

It’s a disruption within that format. Traditionally an art catalogue is about PR and about aligning the artist with a certain set of art ideas. I wanted to use the catalogue to deploy information, just information. I wanted to say that, in terms of my formation, my pillow when I was a kid is just as important as Jim Isermann. Obviously the two have very different values, but I wanted to use that kind of gesture as a way to remobilize and rethink the hierarchy of these things.

It becomes a very pointed gesture, since such a personal bit of information draws the work back close to you, and at the same time this is a work that a public institution is investing a large chunk of money in.

Nobody ever brings up this issue. Instead the work is usually described as having to do with social space, and I’ve always tried to resist that. Work that’s about social space has to come to the table with some approved ideology.

But by mobilizing different institutions and sites and different fields of knowledge and expertise, don’t you think it’s impossible for your work not to map some social terrain or collective arrangement?

The work is very landscape-oriented, but it’s dispersed. I’m not mending anything.

So if you don’t go into these things in order to prove some pre-fab ideology you have about “the social,” couldn’t the case be made that you end up producing some document about your prefabricated ideology that “the social” lacks coherence?

I’d be more happy with that. And I would hope that it would be a complex package. I think the modernist backdrop is a lot more complex and much darker than a notion like utopianism can contain.

Is this something you were getting at by bringing in the reference to Alvar Aalto in the Dia Project (Project, 2002)?

Yeah, it was a reference to Aalto’s sanatorium in Paimio. It was sort of like making an object out of illness, representing it, and sticking it in the middle of this other stuff.

So one of the things discourse does in your work is make it even more discordant, or more self-contradictory or opaque. You introduce a level of discourse or information that goes against the grain of all these tropes of transparency that you get with things like design or utopian avant-garde practices or even aesthetics, even discourse itself.

I have an interest in making art that deeply reflects my life or ordinary things. That interest is not motivated by some sense of confinement in more traditional formal or academic practices. It’s instead about trying to embed my issues, what I’m doing, much more intensely—you know, really looking at something. And if you’re really going to look at something you’re going to unravel a bunch of different positions, different contradictions. It’s about how to make a machine that can present these things, that can give information and at the same time make it clear that this is really more a set of contingencies than an answer to something.

So again this is something you learn from Smithson, this tension between embeddedness and displacement.

Exactly.

But couldn’t you then say that your work is very, very exemplary of the larger situation right now, the way in which spatial practices or embeddedness today is made so discursive, in that more and more people have their creaturely habits informed by discourses on food and wine and clothes and furniture? That these things have been made into value-laden and intensely manipulated discourses, discourses that are more and more subject to almost stock-market-like fluctuations, so that living now, every aspect of living, has much more the feel of a marketplace?

I think one of the differences in terms of what I do and the kind of tendency you’re describing is that, when it comes to J. Crew, they really don’t want people to look into where the person who stitched the patch lives.

What they make is still very much a commodity. You don’t think of the conditions of production. You think of the relationship of that shirt to your watch, the bands you listen to, the kind of food you eat, what your girlfriend thinks of you.

Your fantasies in relationship to an image. And an image in this case would be a lifestyle image.

But today the way that kind of market works is so complex. Compared to the 1980s and the Frankfurt School notions of spectacle and culture industry that were dominant then, today the market doesn’t look so monolithic. There is a proliferation of platforms and niches, different discourses that micro-target certain demographic sectors. The cultural terrain seems more fragmentary and tangled.

But it’s still flat. The ideological engines behind all those things are still the same. They sell through positivity, through positive and non-reflexive forms of identification. The strategies are a lot smaller and more detailed, but at the end of the day an architect who makes a building for General Motors still isn’t going to be able to use information in the façade about how many people died from the mining of that steel. If you look at contemporary marketing and lifestyle industries closely they’re really not so different in their general attitude, in how they hook people, but their strategies are a lot more complex now.

As your work operates within this expanded field do you feel like it takes a kind of stand in relationship to that flat, affirmative tone?

Yeah, I think you can unearth a lot more in my work. You can find contradictions. You can find darkness in it. You can find a lot of things.

Can you give a “for instance?”

I think the pier in Münster is a good example. Being in the center of that lake allows you to have a vantage point, and it sort of opens up, but the walls that actually hold up the pavilion act more like blinders to it. So in order to get that view, that more pastoral experience, you have to go around and sit on the water. Within the pavilion you always face a limitation. And when you get there, there are cigarettes. Cigarettes, on the one hand, are a horrible thing, and yet, on the other hand, if you smoke a cigarette while you’re taking in the view, it’s one of the most beautiful things. So it’s these components that are inserted within a pastoral condition and yet don’t quite fit.

Untitled (1), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Untitled (1), 2012 by Jorge Pardo—Available on Artspace

Do you ever work with clients who will argue if you bring in too much discordance or negativity?

Not so much. Clients that don’t let you do what you want to do are not really the people you work with.

Have you ever refused jobs?

All the time. I was involved with Herzog & de Meuron, for instance, a couple of years ago, and they wanted to use some lights at one of their restaurants. We proposed a group of works, and they started to say there were certain qualities in the lights that they didn’t like. I said, “I don’t think you understand the relationship between what you do and what I do. If you’re asking me to put a work in you can’t go back and forth and tell me what color to make it. The reason you bring artists in is so that you can actually propose a different type of space in the architecture, or a different type of time, or a different type of ideology. If you don’t have access to that then there’s no point.”

So there’s still some element of autonomy operating in your approach?

Yeah, it’s still very much connected to being able to propose an interesting reflexive space within the work. Not necessarily in the more traditional sense of autonomy, in the sense of the work being complete.

But in the history of modernism, autonomy is typically self-contradicting and therefore incomplete. A lot of artists are happy with the idea of working freely or autonomously, but they’re not so happy with the idea of an autonomous art object if that means something like a painting that just sits in the back of the studio taking up space.

I don’t think notions like autonomy have really been thought through. The way we understood it in school, it was something very close to taste. If the work was good, it didn’t need anything, hence it was autonomous.

But you still exercise your taste in your work, wouldn’t you say?

Absolutely. How do you avoid it?

I don’t mean just harmonious relationships between patterns and colors and shapes, but rather your taste for discordance or a certain kind of poetic shape?

Yeah, I try to make things that I like. If you make a work that can absorb somebody because of a certain level of complexity within the form, you have something at that point, and then all these other things that we’ve been talking about can hopefully start to unravel.

To go back to the idea of embeddedness, people today don’t just live in one clearly defined situation or space. Like you say, it’s more complicated. To an increasing degree space is defined by discourses, competencies and marketed lifestyles. And that makes space a lot more of a fugitive quantity. So I wonder how you respond to the accusation that, within this kind of situation, when so much of everyday existence has been made thoroughly discursive and aesthetic, you represent something not that different from, say, Martha Stewart or Oprah Winfrey, one of these people who are so crucial now because of the need for mediators to bring all the different product-lines and consumer discourses together, to create valuable relationships for one’s ever-changing mobile lifestyle and habitus.

Well, I’m a lot poorer than Martha Stewart and Oprah Winfrey, for one thing. But it’s a totally different industry. I don’t really think Martha Stewart is somebody you look to when you want to engage in lifestyle and its actual consequences. Another difference I would point out is that I’m a lot more difficult to instrumentalize than they are. And that’s something that’s inherent in the structure of the work.

Do you entirely dislike the analogy? Do you mind being misrecognized in that way, as something of a taste-manager?

No, because the work doesn’t really set up to deploy those kinds of judgments. If you look at how taste operates in the work, there’s always a kind of contradiction within it. One problem the work does have, though, is that it can be consumed from a distance and made to resemble these things. But that’s a kind of a general problem that happens with everything that’s art. When one actually engages with the work, something else happens.

[related-works-module]