A true painter’s painter, Nigel Cooke creates philosophic dreamscapes are at once playful and foreboding. Combining Old Master technique and postmodern humor, Cooke creates menacing environments populated by recurring motifs like pumpkins, graffiti, trees, and Kafka-esque characters. The PhD recipient (Cooke’s studies focused on animal camouflage) is a visiting lecturer at the Royal College of Art, was the subject of a well-recieved solo show with Pace London in September; he has also exhibited with MoMA, Tate Britain, Andrea Rosen , and Blum and Poe, among other top-tier instutions.

Painting fanatics, take heed: the following interview between Cooke and the British psychoanalyst and author Darian Leader —excerpted from Phaidon’s exhaustive monograph on the artist Nigel Cooke — represents the painter's first-hand account of the doppelgänger cartoons and very un-funny ghouls that inhabit his nightmarish dystopian landscapes. Note: this is not for the faint of heart.

DARIAN LEADER: What is a painting?

NIGEL COOKE: For me, a painting is a wall of questions. It has a great mystery to it, especially after it’s finished. You look at it, and it asks you: “How did you end up here? What were you thinking? Why?” If the answer is “I still don’t know,” then the painting has gone beyond you, taken you outside yourself and you’ve somehow made something authentic. At the same time, it’s wall-like in that it doesn’t yield. It remains unhelpful, obstinate maybe, as it poses these questions. It should anyway. Whether it’s any good, of any interest to others, is a different question and in some ways is beside the point. That all comes later—sometimes many years later. Anyway, the sense has to be that you’ve arrived in a new place, that you’ve learnt something or been through something, and you’re in a kind of stupefied awe in front of these questions.

Can you say more about what you mean by “wall-like?”

I sometimes think that this wall is the product of tackling the main question—why do you need to make more paintings? Why isn’t one enough? Just make one you like, and keep it, and look at it. What is it about painting that allows another one to happen? And I think that for me, the answer comes from a fascination with a certain absence within painting. There’s a void at the heart of it in which there are just more questions: what’s the difference between painting and thinking, or painting and looking, or painting and living? In a way, a painting sits on the junction of all those things. You’re triangulating different threads of existence into one thing and learning about it. I think that’s really what it is. It’s almost as if the point where those things meet suggests an image. And because of what’s happening in those different threads, the image is a surprise to me, and it arrives, not fully finished, but like another question: “What’s that?”

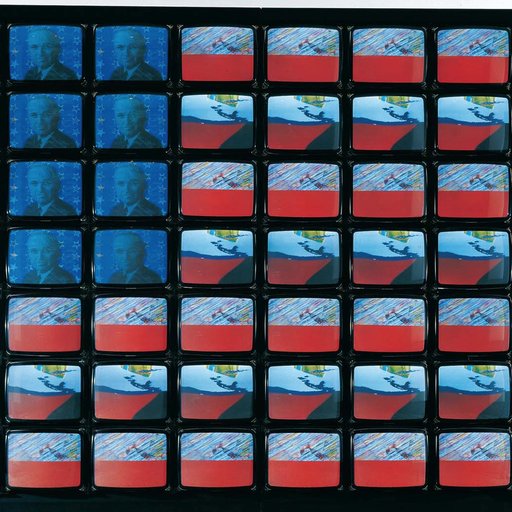

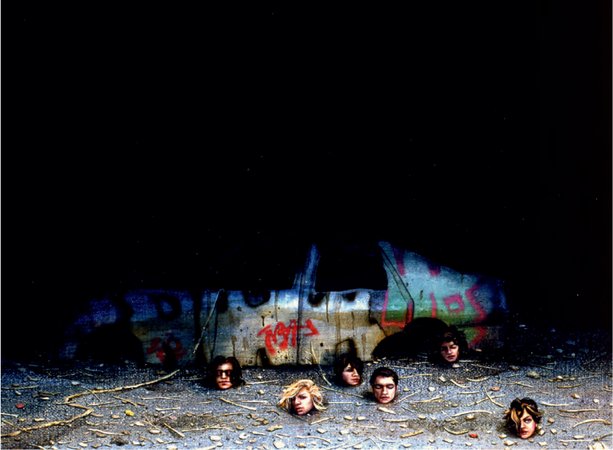

New Accursed Art Club, 2007

New Accursed Art Club, 2007

“What’s that?”

A bit like how you might suddenly be drawn to something in everyday life, but thanks to the stupefying ways of painting you’re extra-puzzled by it—“Why do I like that? Why is that of interest now?” Painting exaggerates that question, builds a longer question along those lines. You recognize that you’re suddenly drawn to something you don’t understand, which suggests the possibility of bringing something into being that you hadn’t been able to conceive of before. What you then have to do is create an articulation for it so that the different aspects of it can be put together, because for me there’s usually some form of incongruity at the heart of an idea, something that doesn’t ft. The job is to plug it all together somehow, in ways that remind you that you can’t really think of any other place where you can put these things together.

Apart from painting?

Yes, I think that’s what it is. It’s more like a limit. The recognition that the threads of your own inner world are frustrating in their lack of congruity. And painting allows them to talk to each other through picture making, I suppose making something look real in a way. I’m fascinated by the amount of absorption of it, the sponge-like aspects of it, the way it can take things in and still hang together. I don’t understand why. In a way, if it was a written thing, with a linear unpacking of something through pages that progress in order and time, I don’t think that would work for me. But somehow with painting everything is happening at once, a bit like music. It progresses in time, but it’s layered in an instantaneous surface moment too. Not in the sense that a story is layered, where you intuit the subtexts as you go along, between the lines, as they say. The material is physically all there at once, as well as in the mind of the one looking at it. There’s a sort of simultaneity to it. Maybe a poem is closer to this because of the great leaps it can make in a small space, the fact that it can join vast differences in place, meaning or context, whatever, very quickly and proliferate alternative senses as it does so. If a novel is a piece of string stretched out fully, then maybe a poem is more like a coil or a spiral of the same volume of string. So it’s piled up, layered one atop the other, but the whole looks very small, or short. Painting has an element of this I think, and also of the layering of music, maybe due to the constrictions of the canvas perimeter holding it in a finite shape.

So it’s very different from the practice of writing for you?

Yes. The sequential feel of writing doesn’t work as naturally for the way I think, on the whole. My writing tends to get knotted up very quickly because of this, and I have to work at stretching out the "string." There’s something about painting being all at once, with competing ideas almost canceling each other out to form a new, total thing, that’s a bit like the way a symphony creates a whole from harmonizing different components. That’s sort of what I have in my head when I start.

Is that reflected in your process of making a painting? I’m sure the painting doesn’t happen all at once.

No, it doesn’t—it’s slow. It goes back to the thing about incongruity. I put down what I think the image should look like at the start, then the paint comes in like an interrogation, trying to make a connection between the things that are now seen for the first time. This part is like a structure. It’s a skeleton that has to be fleshed out with paint; only the paint then warps what the thing is to create an amalgam. The strange thing about this is that I’m blind in a way, immune to the process at one level. I’m always imagining it two or three moves into the future, so I never really get bogged down. It doesn’t bore me, either, doesn’t irritate me. It’s a natural state to stay with it for that long, to see it through, which is obviously completely linear. The blank canvas of a new painting isn’t unlike a blank piece of paper or a computer screen for a writer. It still hasn’t marched forward and evolved. But once the work starts, it becomes very different from the writer’s first moves. In my head it’s about preserving a constant sense of possibility, trying to keep it open and simultaneously balance things that don’t really live together naturally. In this sense, what the painting is actually "of " distorts. And this is how I end up somewhere new for myself. It’s how I’d describe the journey of painting.

Bathers, 2011

Bathers, 2011

In the crudest, most simplistic terms, tell us about the process of creating the work.

The starting point varies. Often, and more recently, it begins with family experiences, time with my wife and kids and small thoughts about that, private emotional moments that might suggest an image. As the girls are growing up there are more and more moments of change, where you notice something has been lost or gained, and that in some tiny way life has shifted course forever. These new moments are closer to what my paintings have always been about, so the paintings have been able to allow the personal aspect in much more openly. At other times, it may come from things we’ve seen together that I want to hold on to or commemorate in some private way. It might be a pile of logs, a tree, a figure, a bird, a building that suggests something to me. The girls may say something about it that amuses me, changes what I think it means. It will draw me towards making a picture of it, but at this point I won’t understand why. Sometimes, it’s an existing painting that sets me off. At others, a piece of writing, or just simply the thing drops into my head in a light-bulb moment. But in a sense, I don’t really notice how a painting starts. The parts are all just swirling around my head all the time. Practically speaking, I suppose the first thing I’ll do in the studio is to try to separate out the different attributes of each idea into a kind of shopping list. I’ll pin ten, twenty pieces of paper on the wall, each with a small, very basic sketch at the top, and start to write below these sketches the components that I see fitting into the scene. At this point, the strongest ones are very easy to spot, so I let the weaker ones sit for a bit to build up a head of steam, and I’ll pursue say four to six of the best ones. I’ll then see what images I have already for each. Sometimes, I’ll have 2,000 photos of one tree, but I’ll see it as having the form of a figure in the painting, so I’ll start exploring who that figure is. If I haven’t got something stored up ready to use, I might start by organizing models and drawing and photographing them, to see what arises in that process. Then I return to the shopping lists with this information to guide me, and some of the features of the other ideas may start to switch sides and become aspects of this painting. So often, twenty ideas will compact down to six or eight in this way. Then I’ll start pushing the paint around, but I try to work very slowly, not to get too sucked in. I just get a day or two in on the painting then let it sit for a few weeks. This way I begin to live with it in a new way, and I can gradually inch forwards with it at the painting’s natural speed. But what I’m really trying to do is not visualize it too soon. I don’t put it on paper in any detail first, because in a way it’s almost like an unopened gift at that point. The most enjoyable bit in some ways is the thing in your head.

You try not to visualize?

It’s like looking at a parcel, thinking, “I wonder where that’s going?” If I start doodling to find out, it gets ruined. This is something I learned from having bad jobs. When I had awful jobs I used to take a sketchbook in to work and draw versions of paintings at break times, thumbnails for paintings, to try to come up with them and feel productive. What I eventually realized what I was doing was setting a "boredom clock" going, so interest would run out by the time I came to do the image. I just knew it too well. So I think it’s that not knowing that I try to cherish for as long as I can, that I enjoy.

So the painting remains open in that sense?

Yes, because in a way it’s all about a suspicion of my own abilities. Painting is so seductive, and if you’ve got any little scrap of skill you can get carried away with that. It can become a quite maddening sort of exercise, whereas when there’s a sort of light-bulb moment, a spark from your personal life and inner experience, there’s something active about that, that you’ve got to try and get into the paint. It has a sort of filmic feel in my head, in a very small way. And in a mini film-making way, I set about gathering props, gathering characters, etc., to match what I want to see and feel. I may arrange a model or a location visit. Maybe I’ll see a person and think they look like something that I’m thinking about. I’ll see a tree, an object, a space. But on the whole it’s usually the other way round, it’s usually that I match something with what I can see in my head: "It’s a tree. What sort of tree is it? Is it a weeping willow?" And it’s then about going off and finding those parts, sometimes with photographs, sometimes with drawings, more and more getting the real thing and observing it, multiple photographs and spending time with it. There’s a certain tree I may find near where I live or work, and I go to it regularly to look at it or photograph it.

1989, 2009

1989, 2009

And with figures?

I often get the person into the studio to draw or paint or photograph them. But they’re not people close to me—they usually have to stand in for something; I’m not trying to literally represent scenes from my life. Those experiences are drivers that allow a painting to happen, but they’re not straight autobiographical scenarios. They have to be filtered to become more generally relevant. But there is a limit—I’m working within the limits of what I can get my hands on, what’s around me. That’s quite a new thing actually; it’s not always been like that. Before, it was almost completely plucked out of thin air. So then I compose the thing from multiple sources and build up the paint almost in spite of those sources. With the newer ones, it’s more about trying to find a way of applying the paint that’s expressive of the thing in a more restricted, direct way.

In what sense?

For example, my work has always had trees. If I look at one thing that’s consistent it’s the tree as a sort of nexus behind a living, thinking character. Maybe because it’s like a brain and a grid at once. And in a way, when I say I’m making them more natural or real, it’s because I’m basically fascinated by the idea of paint showing how light hits something, how it appears in space, but also how it can suggest how that thing grows, and what it’s made of, how brittle it is, how firm and resistant to the touch it is, and how old it is. All of that stuff is really the job of the paint, and I like there to be as much of that as possible. I really enjoy the intuitive, almost unconscious way you can get the paint to talk to the image. And that’s really where all the love is in a sense. The ultimate goal is to try to get the image to feel like the thoughts of the individual character in the scene. Because of how I feel about making a painting—the thing I was saying before about the meeting point of interior pathways on the surface of the painting—well that’s the subject of it as well. In other words, it’s how the painting comes to be made, but it’s also what’s happening in the picture. Just as I draw together different strands of my existence to generate a metaphorical image, the figure is doing the same thing, only those strands are sometimes inside, sometimes outside of his or her consciousness. The paint, and the organization of the painting are what nuance this. Composition, and the range of painterly expressions within that, is there to suggest shades of psychic engagement.

You’ve said that the figures that run through your paintings — the vagabond, the vagrant, the philosopher—are in some sense the embodiments of where you are while you’re making the painting itself.

Yes. The first painting I ever made was a self-portrait. I think really they’re all self-portraits on some level. I don’t know why that is. They’re all trying to get a sense of what it is to be me and use that as a point of departure.

Could you say more about the early self-portrait?

Well, there’s a skeleton in it. It’s typical, I was sixteen. I haven’t really grown out of it. [laughs] There’s a skeleton and there’s a ram’s skull. It was something we were briefed to do on this course, and the frst thing I did was to put a board up behind where I was sitting. And I put things on this board, so there’s a secondary representational plane.

Like in all your later work .

Like in everything I’ve done since.

There’s always a secondary plane.

There’s always a thing behind the thing. Although my work differs, one consistent aspect is that the figure/ground relationship is contained within the world of the picture. So there’s a figure in front of a ground, and that ground is set into a wider context—like a woman is in front of a tree in front of a house in front of a mountain. And it doesn’t dwindle off, or if it does it only does so in pockets, to create a suspicion about whether the distant things are really there. Things block the long-distance view, spatial depth is obstructed. So the challenge is usually to create a landscape that’s also contained, that feels interior. That’s the secondary plane—the boxing-in of space to feel like the inside of one’s head.

Captain's Cabin, 2012

Captain's Cabin, 2012

So what’s on that secondary plane in the original self-portrait?

There’s a sort of draped yellow cloth and then there’s a ram’s skull hung on a hook.

Already a hanging object.

Yes. And it casts a shadow. I’m still fascinated by the shape of shadows in my paintings. So I’m holding the end of the skull, and there’s a skeleton there. In a way, I’m just re-doing that painting over and over. The model for my work was set twenty-six years ago. That painting was so hard to do, so impossible, that I’m still doing it. Maybe all I want to do is make one perfect painting based on those primary principles. And why not? All of painting is contained in them.

Does it follow that sort of pumpkin logic?

[laughs] Which is... ? How do you mean?

Could you define it perhaps?

Do you mean how the pumpkin for me refers to a debased version of your own head? It’s the reorganizing of priorities: I’ve always been interested in elevating the debased aspect of an image to a key position and driving the supposed "subject" to the fringes. I find it funny, I also find it painful, and I ultimately think it’s how life feels. There’s a brilliant scene in Monsters, Inc., where after all the adventures the two main characters Mike and Sully have been through, a magazine features them on the front cover—fame at last—only Mike’s face has been obscured by the price sticker for the magazine. It’s so funny, so typical. We can all relate to that, right? You work hard, you almost get there, then the humiliation comes that puts you in your place, but also confirms something else, some other form of knowledge that your cheap ambition disguised. Sully cringes in embarrassment for his friend, awaiting an emotional collapse. But Mike completely fails to acknowledge the fact that he’s unrecognizable. He celebrates his first front-cover appearance regardless. Has he noticed? Is he play-acting to save further embarrassment? It doesn’t matter. There’s been a shift in priorities, and somehow the meaning has been doubled. That’s what I’m after in my paintings. On all fronts. For me, painting a figure but making it the lesser element, or dwarfing it with something else, is part of the expression. It’s how I try to suggest a ridiculing of the ego, the surges of humility that create new kinds of self-knowledge. And the pumpkin is part of that logic, it’s putting the worst kind of head, the most demented and hollowed-out skull, on a level playing field with other kinds of human representation. It’s reflecting the self-regard of the human sitter in a debased form, at the centre of the action where it shouldn’t be.

Morning is Broken, 2005

Morning is Broken, 2005

So it’s the opposite of how a certain philosophical tradition fetishizes thinking: the head as the organ of pure thought.

A palace.

So more like a pumpkin than a palace.

Yes exactly, it’s empty. It’s that sense of being ill-equipped for the task that I feel driven by. The idea of being in charge of this is foreign to me. And if ever I get to that point, I know I can’t make any more work like that. If I ever feel like I’ve got the recipe, it moves on. I’m looking for that empty bit inside the pumpkin head where I’ve no idea what I’m thinking.

But when you say it moves on… you can see changes in your work over the years but one thing that does seem to be a constant is the presence of these little singularities: the light bulbs, things hanging on hooks, obviously the graffiti, the pumpkins, some vegetables. These things remain despite the other changes we can see in the paintings.

I think there are less of those now. But then, sometimes they come back. In some of the paintings, it’s almost like they’re not there because the character is described as blind in the title.

There are plenty of pumpkins in the painting The Blind Philosopher (2015).

Yes, they’re there. They’re almost like my baggage. But they’re not visible to the person in the work. So they’re like a mass of primitive images beyond the senses of the work’s “subject.”

That’s fascinating. So there’s a tension within the work between your own idiosyncratic baggage and the view of the central character within the painting, who doesn’t see your baggage, the baggage of the one who in a sense has created him.

Yes. In a way I allowed that one to happen because there was a get-out around the sightless protagonist. There was a get-out around whether those things are there or not, in my head. But I feel of late I’ve tried to compress those relationships into more of a field, rather than stand-alone singularities. That sort of monadic figure like the pumpkin, or the vegetable, or the strange object hanging, has been atomized a little bit. It’s almost like it’s broken down into a more seemingly conventional, natural world-view—the tree, or the snow, or whatever it is. I think in a way I wanted to expunge some of those things. I wanted to lay them to rest in some way.

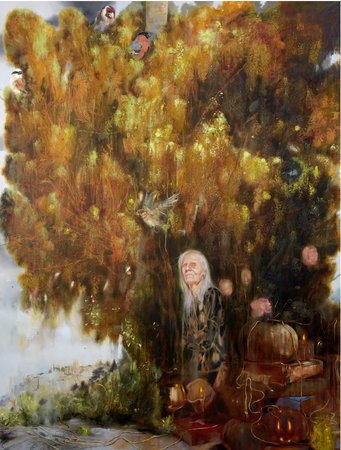

Blind Philosopher, 2015

Blind Philosopher, 2015

In terms of laying to rest, you’ve described your paintings as a graveyard for art history.

Yes. [laughs] I feel slightly differently about that now, I think. It’s more that… I don’t know if I feel like that anymore. In some ways I think what happens—I don’t think this is just me—is that a lot of your early years are a constant struggle with other painting. You’ve got this whole thing about art history around you. It’s a bit of a cliché, the weight of it and all of that. It was a graveyard in the sense that it welcomed everything. I wanted it to be a place where everything could end up. In my head it was more of a positive statement than it sounds. It’s perhaps an unfortunate image, but in a way I’ve always thought of it as quite nice that those things would be able to sort of communicate with each other. I was driven by the idea that everything I was interested in about painting could be simultaneously deployed, in the same way that you’d have a vocabulary as a writer, or a range as a singer or musician. And I didn’t necessarily see certain touches of Abstract Expressionism and Impressionism , and Classical and Renaissance art as being separate, but more as all being vocabulary moments. I almost imagined trying to learn the language across the board. That was perhaps what I meant by that. They’re not new things, their technology is ancient, but they can all be ways of phrasing something, their energies can say different things about the world if used symphonically, if you like. As though they were just different expressions to be used, if one could learn to. All the moments of painting history come to a working relationship with each other in one head—hopefully mine.

Like a pumpkin.

Yes like a pumpkin full of paint.

You’ve talked about your fascination with German and Austrian art. You could s ay that you’ve brought the Casper back into Caspar David Friedrich . [laughter]

Yes, I guess that’s true. I suppose ghosts are a really central motif; sometimes, like Casper, a cheeky, spooky thing that’s completely benevolent. More often, they’re a mournful presence in my work, they’re figures cut adrift and unloved. They’re looking for something, and the ghost is my stand-in for a character that’s lacking is some way, cut adrift. But I don’t think that this is a miserable situation entirely. Ghost stories have a certain melancholy warmth to them. I’m interested in the way the individual has a relationship to the idea of a ghost. In a way, this idea is what a ghost is. We all have assumptions that are based on nothing really, maybe films and books, and they’re held in the mind as a set of principles, either of loss, fear, loneliness, whatever, and these create an outline of some sort of being. In our idea of ghosts there’s usually the absence of the way we come into contact with the world, don’t you think?— materiality, speech, touch—which conveys a kind of isolation without necessarily attaching them to the image of someone we know who’s dead. Putting a bit of this into a painting exaggerates some interior sense of the isolated self. And in a way, it’s not unlike how you the artist leave a trace of yourself in your work. You can no longer say anything in your defense or reach out and make contact. It’s a presence based on absences too. In a sense, all my characters emulate and reflect that.

A lot of the vegetables and the ghouls in the pictures seem strangely friendly don’t they? They’re welcoming and laughing. Happy vegetables. You’ve talked also about your interest in representations of fruit and veg.

Yes. I really like that translation of personality into inanimate things. I’ve always found that life-affirming in some way. It’s a simple thing, but when you ascribe human traits to things that have no consciousness, are you saying something about what they do to you? Is it about you? Or is it an expression of nature as something welcoming? And is that just in terms of consumption and therefore health, or is that a visual thing? I think it’s a nice bridge between the thing, this otherness of the natural world, and your desire to stay as long as you can in it. The range of effects nature can have on you and you can have on it, this co-dependency which can be sustaining or destructive, come together in a smiling banana. It’s the two fingers almost touching on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, life and death frozen for a brief second in a moment of profound lightness.

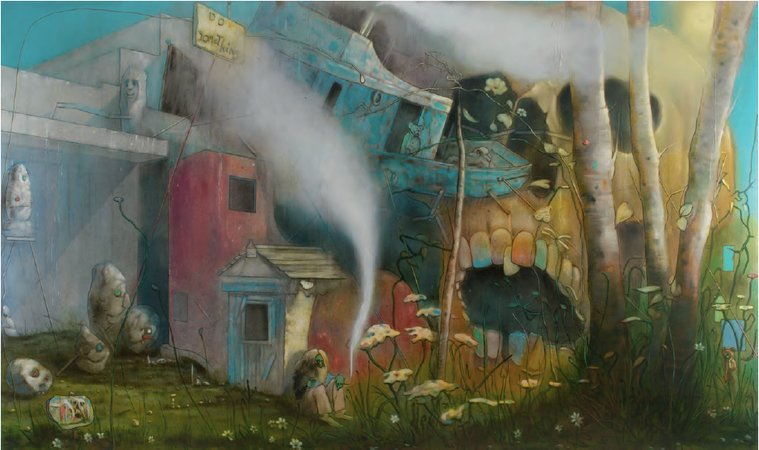

Theme Park, 2008

Theme Park, 2008

When you were growing up, were you equally fascinated by fruit and veg in a dvertising and cartoons?

I can’t remember being so, but I probably was. I don’t know. I always liked it when people dressed up as fruit and veg. [laughs] It always seemed to be on TV in the 1970s, people dressed up, running about. You don’t see it very much anymore: the sun with a face, lots of fruit, cereals and orange juice. There was always that.

Have you been to the Ocean Spray Cranberry Museum in Las Vegas? There’s a really nice cheery cranberry figure to greet visitors.

Really? With a big face? [laughs] I’m glad that’s there. I don’t know why it’s there but that seems like the right place.

Let’s talk a bit about the humor in the work. One of the striking things is the way that you combine themes of the utmost seriousness—life, death, creation, growth, decay—and this dark humor that runs right the way through.

Yes. In a way you think about humor as the humanity of it. It’s a way of getting another perspective into it. It’s also one of the only responses to irrevocable things. There’s a strength and a grandeur that I find inspiring. I’m not just talking about laughing in the face of death, or gallows humor, or those sorts of things. It’s partly about that, but not exclusively. It’s also a mechanism to say that the heavier aspects of the image can have a sort of reverse thrust, that they’re able to express in another direction at the same time, with different values and consequences simultaneously. And this is the role of the humor in a way: it’s taking away the singularity of the statement and turning it into something with an alternative. It’s perhaps an odd comparison, but in the first Star Wars films, there’s always the element of randomness and comedy to the actions of the good guys, which counters the ruthless commitment of the bad. The dark and the light exist perfectly alongside each other and represent different things. Darth Vader isn’t trivialized by the antics of Han Solo and Chewbacca, but they exist simultaneously.

Could one historicize and contrast a period of art history as characterized by the Screaming Popes and ours by the Screaming Pumpkins?

Perhaps it’s just that the straightforward expression of existential angst is embarrassing now. No one has an audience that thinks like that. It’s like you need to show somehow that you know what the different levels are to any form of expression that talks about life and death. And it’s not about showing that you don’t mean it, which is the default method for not being held accountable for dealing with big themes, not being called out for sentimentality or corniness. In that instance you’d just include a little hint that it’s all a joke, getting you off the hook. It’s not that. It’s more about being able to hold the two things together at the same time, the dark and the light, and that captures something of what it’s like to be alive, of what existence is on an everyday level. You have this weight over you at all times, this potential for catastrophe, but survival is about cheating that on a tiny level every day, about the joys we find in the methods we use to cope with that weight. And there’s a humor in that, there has to be. It’s the heart of humanity—surviving, getting away with stuff and winging it, seeing another day. There’s a certain sort of beauty to that, I think. I find it quite inspiring somehow, that life is both together always. In a way, the Screaming Popes are quite funny now too, maybe for the same reason.

Another theme that you’ve mentioned is the idea of merchandising within your painting. I like the idea. Can you say more about that?

I think sometimes the trajectory of the image in the painting can go into tangents that crystallize on their own, in the same way as in an economy, certain things can crystallize and then evaporate. You get little micro-trends bubbling up, becoming things, then going away. A painting has that sort of microcosmic reality if you want it to, and I like the fact that a tangent in a painting, a spin off, can be realized, manufactured within it. If a character is doing something there’s nothing to stop you having the T-shirt or the book as a way of commemorating that, or maybe making a mockery of such traces we’re desperate to leave behind. Because that’s what life is like: you’re always leaving these trails of commemoration. But you are factoring in these trails of commemoration.

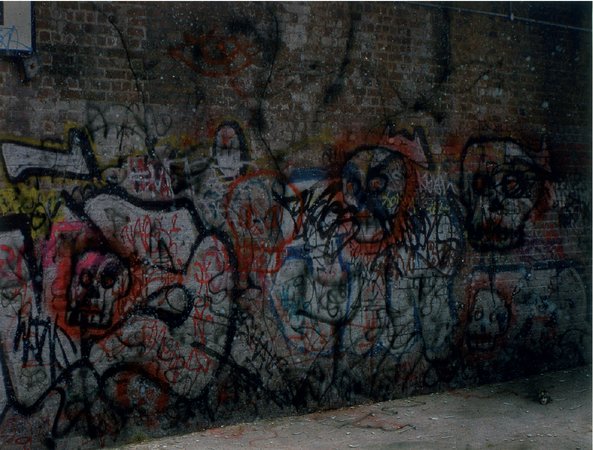

But you are factoring in these trails of commemoration within the painting. And that brings us nicely to the question of graffiti in your work. Why is this such an omnipresent motif?

It’s quite strange because when I started doing it, there wasn’t any such thing as graffiti art in the way it’s thought of now. There was graffiti, but it didn’t bear any relation to the art world. It was out there, sort of on the fringes of it. It had its own world. For me, when I was making that work at the time—and this does connect to the idea that it’s about whatever is in my immediate environment—it was everywhere. First of all I liked the idea of illegibility. You could see it was a word but you couldn’t read it. So there was this slow version of a communicative phrase. It was on a flashpoint between linguistic and pictorial sense. And then also, because in the street, on a wall, it’s fast, the spray comes out propelled by compressed air, it’s almost like the opposite of a brush. And so to render that with a brushstroke is funny, slightly perverse, but also an affirmation of what painting was like at its best, the slowness and incommunicable silence of it, its unreadability. It’s another way of having a different voice in it as well—painting like another person as well as yourself.

Skull alley no 2, 2002

Skull alley no 2, 2002

This again seems very important in your work, the idea of having a different voice within your own painting. Why should a painter have only one voice?

I think it’s about dialogues and opposites, dualities. If darkness and humor are equally present, then the language of painting could embrace its opposite. There could be a secondary voice in there that thinks differently from you, has different intentions. In a novel or film there are the tensions held between characters, and I’d like painting to have a little of those tensions, that set up a question as to where the values are. It’s going back a bit to that point about the debased thing at the centre. If your primary intention is to paint a wall beautifully, then why, like in real life, can’t there also be an individual whose primary intention is to destroy the perfection of that wall and leave their mark? To show the two together is a common combination—you set something up, someone has other ideas and wants to bring it down. But also, at the same time we can often feel such ambivalences ourselves. We don’t always think about things in these neat demarcated ways, if at all. To me, it’s more common to have mixed feelings about almost everything. In a way that’s what I’m trying to put across in all my work, those mixed feelings, that the mistrust of neat boundaries can extend, and should extend, to making paintings. Do you really believe that I’m cast-iron confident in every move I make? Of course not. That’s not what creativity is. It’s all doubt, all ambivalence. My use of multiple voices is about highlighting that. Equally, it’s an extension of the role of the figure. If there can be a figure in the scene, then their actions can also be represented. What’s to stop those actions being set against mine? They can easily represent a different set of values. How do you shift between them? If you use the same material to paint the sky, a tree, a rock, someone’s flesh, a pumpkin, whatever, it’s all the same material. How does the information get into it to change the texture and the sense of it into something else? What turns the paint from one thing to another, and how do we read the value and intent and purpose of that thing in a set of relative values?

You’ve talked as well about painting as information, which is a lovely inversion of fashionable views about painting being anti-information or the opposite of information. Can you say more about this idea of information, which you’ve linked to entropy?

I think for me, it’s about the inertia of the material. Paint begins life as this stuff just sitting there. Somehow, when painting, something gets added to turn it into something we recognize. So a blob of green paint is sitting there—you apply it to the canvas, and with a couple of changes it can become a leaf. What’s changed? Maybe the outside shape has changed, the direction of movement, and the speed of the touch. The speed of the touch will suggest the hardness of the surface, and its ability to reflect light. The shape will tell us something leaf-like. What’s been added? It must be information, surely—or at least the category of information. You could call this a scale between inertia and illusion—on the one hand you have a blob of paint and on the other you have something you want to touch it’s so convincing. To get from one end of that scale to the other you have an injection of information that can be understood on some level. Into the colored mud an idea is added by the painter, a collection of information equalling ‘leaf ’ that the painting can convey to a viewer. And oddly for me it’s quite magical, I don’t really know how it happens—why one thing can look like that and then the next minute it doesn’t. What is it really that changes a blob into a leaf?

And what changes a leaf into a blob when it decays?

Yes. So the entropy thing is its return to the inert material. How does the information deplete? When some leaves slip back into blobs from being leaves.

Why do you see that in terms of information?

I suppose it’s this scale, from inertia to illusion, because there must be an aspect of communication for the thing to be recognized. And to communicate, to enable recognition, there should be information. To convert the inert mud to a figurative image is about making the mud an understandable and therefore shareable proposition. It becomes a model for thinking about how the world is organized.

With that idea about the conversion of information sharing, you’ve described the process of painting as like Chinese whispers.

Yes—you start with an idea, then it mutates as the information gets into the mix. Painting is about call and response. You put something out, but something else comes back. It’s a version of what you thought, but it’s modified by countless variables in the chain of command between the mind, the eye, the hand and the canvas.

Which presumably implies less the transmission of information than the distortion of information, the transformation over time?

Again, I think ultimately it’s something about scales of information. Scale is a central thing, because at the highly detailed level it’s compacted with information. There’s an accuracy, there’s a tightness, there’s a compression of data in describing this tree or this building. But the job of the painting is then to remove that information at a wider level, so that it doesn’t say anything. In a way, it’s trying to break that temptation of the painting to just communicate directly. In a more prosaic frame, it’s like saying, this is an abstract painting . On a different level, it’s about how do you make an abstract painting with recognizable things? It’s a funny thing to say, but really what I mean by that is how does a painting become recognizable? You can make an abstract painting by doing nothing. You can just put a blank canvas on the wall, maybe you could add bits of stuff. You can say it’s not a very good abstract painting, but already the reduction, the subtraction that identifies abstract painting as taking place is happening. We’re in a conversation about abstract painting. The question for me is, how can you stay in that conversation as the painting is pushed forward towards the recognizable? How can you hold the value of abstraction even as information is piped in from the real world? Because like all the ambivalences at work in my approach to painting, the one between the abstract and the recognizable holds them all together.

Don't Mess with my Message, 2002

Don't Mess with my Message, 2002

If we take an example, you mentioned once that you were on a bus and you over heard two people having a conversation about a UFO having stolen a cow’s genitals, and you thought you’d transform that into a painting.

Yes, that moment was an unusual one. I’d just moved to London and was struggling to follow on from my previous work as an undergraduate in Nottingham. I wanted to find a way of breaking the spell of my degree show, and some of the seductions of that life that had made me feel, falsely, that I could become a painter. I was stuck in a rut, trying to replicate paintings I’d done before, and I needed something arbitrary to break it open. I was lucky it was that, a hyper-specific, anecdotal, bizarre story. But maybe it was because of the story rather than me looking for it. Maybe it wasn’t just a happy accident. It was obviously that story that allowed the thing to happen in some way. I must have heard a million things that day that could have been used, but it just happened to be super-strange. In a way, that was like buying in something from the outside world to save my work from vanishing into itself. I was tackling the question of how does a painting actually still be a painting in its own right rather than just a description of a known thing. The painting was a failure but it was an exercise. What it showed me is that you can’t “talk” in painting like that. It was the wrong tone of voice. What you’ve got to do is take the words, “cow,” “genitals,” “UFO,” out. So, you can start with that but in the end those things have to go.

So it’s removing the information?

Yes, communication can happen in an atomized way, but not in totality. If you leave in moments of communication—this is a house, this is the sky—but take out all the other messages that help spell out what it all amounts to without question, then you’re left with a painting. So what is that? This thing that’s left over can be driven by those communicative things, but it can’t be about them. That’s what I mean about packing in information from the beginning to the end. You can pack it in but at a certain expense. The expense is that you work to separate one kind of information from its neighbor, so that it doesn’t all join up into complete sentences to help you out, to give a straight answer. The painting still has to remain silent, mysterious, uncommunicative, even when packed with data. That’s the expression I’m after, information at the expense of communication. That painting of a UFO was an example of when there was no expense and it failed. It was useful for the next thing but in itself it didn’t work. But what it taught me is that paintings can’t talk, they shouldn’t.

When you say that paintings can’t talk that doesn’t stop there from being voices in a painting.

No. What I then thought is that it’s all about cancellation. If there’s a statement here, its opposite is stated somewhere else. For every assertion there’s equal weight added to a question, a doubt. In this way it’s all held in this ambivalent limbo of self-cancellation. In a sense it’s a bit like a monochrome —object, image, form, language all canceling each other out in a single implosion of difference. I’m trying to do that with the language of pictures.

An art of cancellation?

Yes. It’s a camouflage thing, too. That was a moment for me, thinking about camouflage, how there can be all this organization in an insect with the aim of invisibility, the vanishing of that information, that dual function of elaborate information arrangement cancelled and disappearing the thing.

You’re referring to your PhD, which was in part about mimesis and camouflage.

I think it came out of that. In a way my paintings have always been about nature. The earliest things I was interested in were landscape paintings and paintings of nature. I’ve always tried to sense or intuit a painting’s relationship to the natural world, but I also try to build into it a non-picturesque approach, which is to do with things you bring to bear as a thinking subject in front of nature. So it’s about the things we see in nature that are thought as well as seen. It’s that collaboration between those things—what we see, and what we think whilst we see. I looked into the idea of insect mimesis, of natural mimesis, which is the way a creature such as a leaf insect can copy its environment to hide. Mimesis is the way an insect mimics a leaf with its own body to evade predators. I used this as a way of thinking about how scale and information can relate and undermine one another. With the mimetic insect, it’s about how the perspective you take on the living system—the insect—changes what that system is. In other words, the bird hovering above the moving shape on the ground can only see leaves. It can’t tell that one of them is an insect, as it has become invisible. Yet at ground level, you could probably find it looking closely, and at a closer level still, at a microscopic level, the construction of the insect as an organism is completely different from the leaves around it. So the organization of information is, in this case, in service of the disappearance of that very information in camouflage. It exists in order to make it vanish. And actually you can organize a painting that can have several perspectives all at once, not just in terms of angles of view but in terms of attitudes, values, tones of voice and distance signifiers: where things are, how far away things are, what they’re made of and what they’re obscured by. In a way, these are all ways in which a painting can creep towards an absolute, which is what a mimetic insect against a similarly colored background is like: an absolute moment when it’s invisible. Is it there or isn’t it there? It’s sort of both.

Do you want your paintings to have the same status? Visible and invisible at the same time?

The painting has to be ultra-clear but not really say anything direct. It has to be highly rendered but abstract. It has to be two things but also cancel itself out. And I don’t think you can do that without information. It has to be a perverse relationship to information. I don’t think it’s conventional, it certainly isn’t scientific. It’s perhaps more of a metaphor for an overactive relationship with painting. [laughs] Perhaps more accurately it’s the fact that I’ve given myself an impossible problem, that curing painting of its complexity with pure reduction isn’t in my nature. I’m interested in the tensions that arise from collisions in expected meaning—what is a landscape, a gestural abstract painting, a skull, a portrait of an artist? These things are freighted with expectation, and I try to unpick them so you get to something different from its collision with some other way of looking at that thing. To have the picture hover between absolutes is the outcome of abstraction and figuration coming to a stalemate. And it’s the tension of that stalemate that forms an ideal expression for a living, breathing ambivalence and doubt that we all can relate to on some level.

The Dead, 2005

The Dead, 2005

You mentioned that one of your earliest interests was landscape and now there seems to be a return to it in your work. Can you say something about that?

Yes. The earliest paintings I was fascinated with were by my grandfather in his house. He had a big house. And it’s weird to think of it now: in that area you wouldn’t really see real oil paintings in people’s houses that often but there were loads of them, and they were all landscape. And I’d spend a lot of time looking at them. This was one of those houses where you were left alone quite a lot and you’d just mope about and do your own thing. So spending time looking at small landscape oil paintings was quite an early memory for me. And in a way I can remember being struck one time by the question of why the cloud was behind the mountain, why things were in front of each other when in fact they’re not. What is it that creates that space, what is it that makes it believable? I remember just thinking, looking and staring at this thing: “I don’t understand how that’s possible.”

Possible?

You look at the surface of the painting at an angle, and it just looks like muck, terrible—no illusion, no magic. Then back to a front-on view, and it all just clicks. I thought: “What are the properties that allow that material to create a space?”—though I wouldn’t have been thinking in those sort of words. It was just a shock that it made any sense, when really, looking at what it was made of from the side, it was like cream cheese spread on a biscuit. How does it work? And also around that time, my primary interest was in nature, biological things I suppose. Natural history was my big love as a kid, so the two things were quite closely aligned. I was always outdoors collecting stuff, examining it and drawing it. The fact that my grandfather was a vet as well, and the practice was in the house where all these paintings were is all sort of tied up. Often animals in cages would appear. It was quite a weird set up. In a way that was quite formative, but also maybe it was something about the atmosphere. One of the things about those paintings that I love is the idea of atmosphere, in quite a simple way. I think that my work has perhaps taken a journey from something intellectual to something atmospheric and emotional. When I first tried to understand why my paintings weren’t successful, I did what many young people do, which is to fall back on intellectualizing, wanting to work it out and justify myself. You don’t really believe in wisdom and experience, you just believe in the brute force of logic and try to figure it out. What I’ve come to think is that it doesn’t really help. It can give you mechanisms to describe it. In terms of understanding what painting is, I’ve started to feel that you’re sort of formatted before that to make the work you’re able to make, or you have yo make. I think formative experiences are central to what sort of paintings you’re able to make, how your decisions about what is permissible come to be. And I think since my work has become less linguistic, less describable maybe, certainly less intellectually driven, more emotionally driven, it’s returning much more to those core source interests, like landscape and the depiction of trees, light and weather.

What was it in landscape that originally attracted you?

I think it’s the idea of just entering something, another place, like walking through into a different space.

Thinking, 2004-2005

Thinking, 2004-2005

Which is still in a sense one of the most striking things about your paintings for the viewer.

Yes. It’s real but it’s completely codified. The scales are wrong but you want to go in. It’s a vessel. It’s not a surface, it’s punctured. And within that, your consciousness can just leak in. And there’s a communion with something in that which I’ve always found very melancholic. And melancholy is the heart of a sort of poetic desire in my attitude to painting that’s come and gone over the years. You can’t say that those figures with the baseball bats and bottles are poetic, really. They were brutal and quite hard-edged things, but that was how I felt then. It changes as it goes on; you have different life experiences. Unless you’re a complete charlatan, painting can’t be the same as you change, I’m sure. Unless you hit on something early on like Lucian Freud , Giorgio Morandi , Francis Bacon, people like that who have parameters in which all of life just tips in. In some sense that’s what I’m getting onto now, learning that actually, all painters have those parameters. And when you’re young you just don’t see them. You think you’re constantly charging off in all these directions, but actually you’re just going back to the same thing.

Which is for you?

A sort of multi-layered arena, grid-like and tree-based. Often either an architectural or Arcadian set up, which has figures and things happening in it. A bounded world with finite ingredients.

One final question. Looking back at your work over the years, one could say that you have at least two different uses of line to make the contours of your figures. You have the more classical, natural realist approach to figures that we can see in more recent work and then you have the kind of cartoon use of bold line as contour. You’ve talked about the importance of Michael Craig-Martin at a certain point in your work. Can you say something about that change, that difference within your painting between the cartoon-like figures bounded by this very definite line, and the others?

Yes. It’s something that I’m troubled by a little bit. I think that at a certain level, I do all my working out in the paintings, so my development is there to be seen. If I could go back and just conceive of the next step, rather than paint through it, it would probably make more sense. But in a way, it almost makes too much sense. It’s almost like the graffiti line just stepped away and expanded to the point where it came off the wall and became the figure, and then the figure stepped out of the silhouette and became rounded. It’s like drawing a creature that springs to life. It was fulfilled. I willed it. It was a little pumpkin in a one-centimeter square in the corner that grew into a bigger pumpkin, then a bigger pumpkin, hopped off the wall, grew legs. As I was saying earlier, I was interested in giving such marginal components undue or inappropriate status. The same can be said for the devalued images, of which the pumpkin is the key example. They were given prominence for a while, as a way of talking about the perverse value system in the painting by exaggerating the useless and value-less aspects of the imagery. But in the end, those values have transformed into something else yet again. The paintings don’t discuss those things as directly anymore, or in such a distant, intellectual way. That’s the sort of thing that was worked out in thought as much as in paint, where now there’s more happening in the painting, and I think less about that sort of issue of reception and value, more about what matters to me personally. In a way, it’s all about what’s left out now, what a figure in a certain scenario can suggest about a certain point in life and time. Really, it’s the emergence of a breathing protagonist out of a cypher, but still a notional protagonist, one that might not really be there, a ghost. I think that it’s like this strange realization I had, that I’m not haunted by paintings, I haunt them. I go to museums and look at them for hours—all these old ghosts, long-dead men and women. But it turns out I’m the ghost, not the paintings. I’m the haunter. That’s why I called one recent work I Was the Ghost. It dawned on me that I’m the thing. [laughs] I’m the problem.

That’s great. But in terms of the sequence, should it be the ghost that becomes the cipher or the cipher that becomes the ghost? What does it mean in terms of the chronology in your work?

It means that in the beginning, I thought I was the palpable being and the painting was the cipher, and then gradually, over the years, those things changed place. [laughs]