The Los Angeles-based art world superpower Paul McCarthy's wild showmanship has disgusted, shocked, and delighted onlooking audiences since he started making his visceral video and performance work in the late 1960s. With all kinds of voyeuristic debauchery in his productions, installations, films, and "paintings as action," McCarthy has gained fame and notoriety, most notably as a veteran of art world kingmaker Hauser & Wirth and for stealing the limelight at the 2013 Park Avenue Armory Show with WS.

From Phaidon'snewly revised and expanded monograph Paul McCarthy,the artist, curator, and historian Kristine Stiles interviews the showman about motor oil, ketchup as blood, and vaginal mayonnaise.

[Paul McCarthy]: I started making videotapes in the early 1970s. The first ones were around perception and illusion. The camera was upside down, or I’d use mirrors, things like that. But I also started making pieces that were performances in the sense that I would be in front of the camera. I would work in the studio primarily by myself with the camera. There was not much in the room. I would do some things and record them. They were often repetitious and intuitive. Ma Bell was one of the first actions that I did which involved liquids, in this case, motor oil. I had not planned to make the piece. It was spontaneous. It was the first tape where there was a persona.

This aspect of performance is illusive. For although the actions are experiential and being produced for sensations, they are also part of the object being made. What does it mean that an action is equally an object? You arrive at “something” that you’ve been waiting and looking for—but also not waiting for (because you have also just been doing actions for the sake of the action itself)—and you then try to recover it by recording it.

In those situations, I would most likely work in the studio alone. There wasn’t much else in the room, maybe a few objects that would become props for a tape. I would begin the actions. I would try a number of things and it might take a minute to recognize something in it. All of a sudden I would key in on what it was, or I would recognize something in it. I was pretty aware that I was actively trying to find something, to put something on the videotape machine.

I was experimenting—experimenting with the camera in the room, with the mind, with the props and the actions. I was experimentative when something seemed to happen. Then I would repeat it, refine it. The refining usually meant heightening the experience. I was interested in spinning, and I would often spin in front of the camera. I got to a point where I could spin for 30-40 minutes I would bang my outstretched hands against the wall, that helped me from getting disorientated and dizzy. The intuitive action that I kept returning to became an involvement. I still make actions and sculpture that relate to spinning.

The action I found most interesting in the Basement Tapes was Whipping a Wall with Paint. Some quality in that is present in all of your work and comes through in that particular tape. It is a lurking violence, a presence just on the verge of being unleashed, some kind of horrific terror or force.

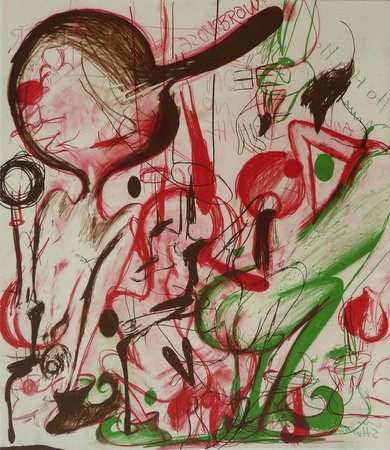

There were actually two tapes, one which you call Whipping a Wall with Paint and a second version which was Whipping a Wall and a Window with Paint. Passers-by viewed the action from the street, on the other side of the window. I splattered paint against the window for about an hour and in the end of the windows were covered. There’s paint everywhere—on me, on the floor. I would dip a big blanket into a large bucket of a mixture of paint and motor oil, pull the blanket out, and slap it against the wall and the window. It was exhausting. The splattering of the paint or the residue of ketchup as in Bossy Burger or other pieces seem to suggest that an act of violence has happened.

Well in fact an act of violence has happened.

Even the ketchup in Bossy Burger—the motor oil and the ketchup—both refer to the splatter of blood splatter, and also to paint.

It’s not the direct, obvious, accessible metaphors that interest me so much in your work. What’s more compelling to me has to do with what isn’t there, this latent violence the manifestation of which is unclear as to what is will become. It may not become violent at all. I could become whimpering or sobbing or laughing. But it never quite gets expressed. I identified it in early and late work: in Whipping a Wall with Paint, in Bossy Burger, and in Painter. This latent quality occurs most strongly when you are going in and out of doors, and around tables, and in between architectural settings. At these moments you seem to be meditative, almost performing a mantra-like action; latent with explosive material which may or may not be violent. So the metaphors of blood and all that are not so interesting to me. It’s what is just on the verge of being expressed, but never is expressed. This is why I wanted to think about the question of beauty in your work, to move from the manifest to the latent center of your work.

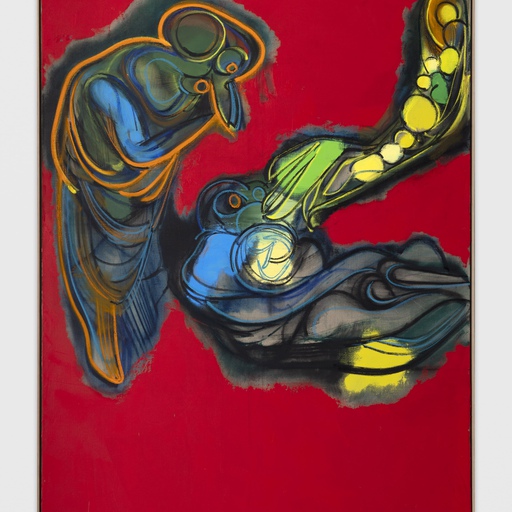

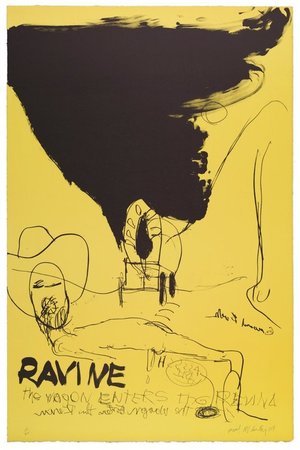

Untitled 16 (Ravine, The Wagon Enters The Revina, Yellow), 2009

Untitled 16 (Ravine, The Wagon Enters The Revina, Yellow), 2009

There is a kind of self-hypnosis involved in going from space to space or from menial action/task to menial action/task. I think that this work “latency” implies that something is not resolved, but I do think that there are moments of resolution in my actions. Maybe symbolic resolution. They could relate to forgotten memories—my traumas or possibly someone else’s traumas. I seem to have a strong interest in placing the action in architecture and in using furniture: rooms connected to rooms, doors, windows, and hallways. The house itself and the action of going in and out of its rooms. I always use tables; tables being a pedestal, something for me to stand on where I become figurative sculpture. The table is also a kind of altar, or a place for food preparation. I think it has to do with the search for a very basic kind of activity.

The world is ordered by those actions and those objects, and when I say “latent” I don’t mean to imply a lack of resolve but a potential still dormant in the action that is compelling, in some ways terribly frightening, but also absurd, humorous, and something that asks for empathy but is never overtly expressed.

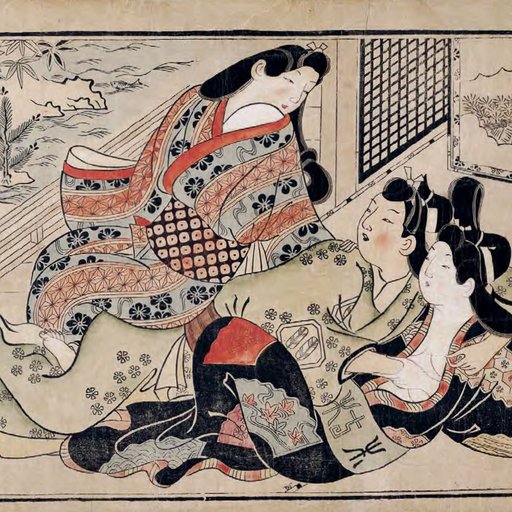

It reflects a kind of order, or cultural order. The action of the altar is primal; it involves the body. The altar becomes the place where the sack is cut open—the human sack is cut open—the body sack or the animal sack, the sack meaning the skin. We search for what can’t be gotten at in the interior of the body, cutting open the body to peer inside. In my work there’s a kind of theater of that, and by theater I mean the use of representation. The object becomes the body—it doesn’t need to be me, or even another human.

I operate in a kind of theater. I use objects to represent things, to represent thoughts and feelings. The objects don’t necessarily have to relate to themselves, they can be a symbol for something else. Ketchup can represent blood, it’s not necessary that it be blood. There were pieces that I made in the early 1970s where there was a sort of emphasis on concrete performance. Performance as a concrete reality, where you don’t represent getting shot, you actually get shot. That definition of performance as reality—as concrete—became less interesting to me. I became more interested in mimicking, appropriation, fiction, representation, and questioning meaning.

I’d like to go back to the role of architecture in your work because your action within certain kinds of architectural settings suggest some personal memory of an actual experience that is no longer recoverable but which comes through most powerfully in architectural spaces.

I think that in part my work does refer to my own private, forgotten, or repressed memories and that I seem to play them out unconsciously in my actions. It is from those repetitions that I recognize them as existing, but I am not sure how they relate to me. Are they specifically my trauma, or someone else’s that I have witnessed either directly or through the media?

But the definition of performance as only being real or performance as reality is limiting; psychologically or perceptually I found myself giving it a new reality. At one point I said that “my face on the floor is my face on your stomach.” It has to do with the view of performance as a reality. I’m proposing that reality itself can fluctuate. The bottle of mayonnaise within the action is no longer a bottle of mayonnaise, it is now a woman’s genitals. Or it is now a phallus. I suspect that that suspension of belief does exist within viewers, even though they cling to the conscious interpretation that ketchup is ketchup. I suspect that they’re disturbed when ketchup is blood.

I don’t think so. I never lose sight of the names and functions of the objects that you use. I’m not disturbed in your work; I’m touched. You’re suggesting that there’s a suspension of belief, that it works metonymically: ketchup is red and viscous, and therefore it has a phenomenological continuity with blood.

Yes.

I have no argument with this. But the effect of your action hasn’t so much to do with the symbolic meaning (or transference of meaning) as with a connection to the fact that you actually do the action. The question then is: what does it mean for Paul to make an action that transforms a bottle of ketchup into a vagina?

For me the actions go in and out of affecting me differently. It is this quality that I feel again and again when I watch the tapes, even from the beginning up until now, for 25 years of tapes. There’s this aspect of getting into something repetitive, going with that repetition to the point of discovery, and then sort of letting go in that space. I never get involved specifically with the actual materials or making those kind of metaphorical or metonymical connections. Or transformations or representations of materials.

But you use the same materials repeatedly, so clearly the repetition in the performances is significant. But it’s not where the content of your work lies for me. I think the repetition, the objects, the characters, the bodily fluids are all a kind of camouflage, a mask, but more than a mask. They function as a smoke screen that detracts the viewer from the latent content in your work.

The repetition lets you know that they are specific to the actions. I’ve often thought that the actions between 1972 and 1993 were dependent on liquids. I’ve often thought that particular types of objects—holes, bottles—appear all the time in my work. Architectural references are all obsessive in the same way. And the masks. The mask in the sense of it being an environment, almost an architectural environment. When my head is inside the mask, I’m peering out of these holes which are an inch or so away from my face. My voice changes inside the mask; it’s hard to breathe. I also make this connection of the mask to a camera. The eye hole of the mask is similar to the lens hole of the camera or the frame of the picture. You can’t see beyond the frame of the hole. I’ve made this hole metaphor as a metaphor of cultural control, what you can see and what you can’t see. That wasn’t something that I recognized at the beginning but which grew out of performing.

I started doing those performances and constructing pieces around the eye, the idea of a hole, of looking through something. This was both a cultural metaphor and a personal or private metaphor. And that was one of the things that was interesting to me about Duchamp’s Etants Donne…, that you look through the two holes and you can see only what he wants you to see. You can’t see anything beyond the frame of the hole. You can’t see what the object looks like above or below the frame of the hole. You can only see what the hole allows you to see. My early black paintings, from 1967, were done as doors. I understood all Western art in relationship to mirrors, windows, and doors. Painting has always had a reference to architecture.

A lot of your activity goes on in between architectonic space. This discourse is one of framed space, but a frame (unlike the hole) that is certain. Curiously, it is also a space where you do a lot of talking. For example in Painter, you say things repetitively: “I can’t do it”; “I think I will,” and so forth. At the same time it seems to be a space of contemplation for you.

It may have to do not only with my conscious and unconscious memories but also with my difficulty in accepting something versus nothing, existence versus the void. They may be related, they are related. The use of architecture is associated with constructing a place, framing, objectively and existence, ordering, substitutes, necessity, and absurdity.