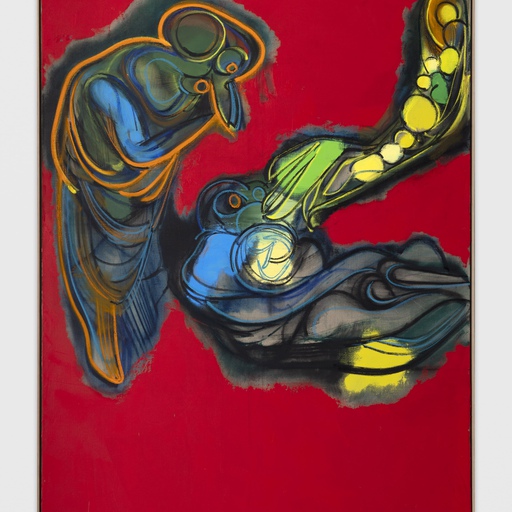

A celebrated pioneer of experimental video art, Pipilotti Rist makes work that exists somewhere between the realms of fine art, music videos, advertising, and psychedelia. Channeling her DIY ethic from her past as a Swiss pop star (in the band Les Reines prochaines), her works combine sardonic wit and an immediately recognizable style of oversaturated colors, epicurean imagery, and playful eroticism that take form across the mediums of video art, audio installations, and two-dimensional pieces.

In advance of her retrospective at the New Museum opening this week, we're excerpting this interview between Rist and the renowned curator Massimiliano Gioni from Phaidon's new monograph Pipilotti Rist: Pixel Forest. Read on for a rare glimpse inside the mind of one of today’s most audacious artists.

Massimiliano Gioni: When did you first start making videos?

Pipilotti Rist: I didn’t start with video right away. I worked first with Super 8 animation films and slides. I was mostly doing stage effects for music bands, creating films and images to be projected during concerts for bands like Billion Bob and the Family or Les Reines des Couteaux. So the wish to work with video was in the beginning very practical, as I wanted to use different technologies that would allow me to make dissolves and color changes as I worked on these light and sound shows.

Working in Super 8 was always very expensive and had more layers to it: you needed to send the film to the studio to have it developed and really work on the material; it was never immediate. I thought that video could give me more freedom. So in 1986, when I was twenty-four, I enrolled in art school in Basel, in a second education course for people who already had a profession, and I went there with Muda Mathis and Omi Scheiderbauer. The idea was that by going to school we could have access to a camera and to an editing table. That’s a big difference from today: at that time, in the middle of the 1980s, you could not do the editing on your own computer, you needed to have access to a real and heavy editing table.

Who did you study with in Basel? And whose work were you looking at, at the time?

My teacher in Basel, René Pulver, was extremely knowledgeable about video art, which was great because I didn’t have a particular interest in video art up until that moment. He had a collection of films and tapes, which he showed us in class. That’s how I discovered and saw many video works. You have to imagine that in those days people were using magnetic tapes in various forms—from one-inch spools to many other different types of half-inch tapes, like VHS. It was less easy for works to circulate. And there was no internet, so it was hard to get information about other artists working in video or see tapes unless you had access to someone with a collection.

Were you thinking of yourself as an artist at that point? Or did you consider yourself just part of the music scene?

I’m always very suspicious of self-made histories. But the human brain sets everything in a logical order and tends to forget the many coincidences that are probably what really determined what happened. There is no linear logic or straight narrative, but in the end that’s how we like to remember it, especially when it comes to our own biographies: we project a chronological order that was just not there. So probably everything I say about this time, when I was studying in Basel, is not really true. Or maybe the way I describe it is just the way I wish it had been.

But to try to answer your question, I didn’t think of myself as an artist and didn’t think that’s what I wanted to become. I thought I wanted to create rooms where people could find themselves. I was convinced that music and dancing are, in a way, reflections of the inner body. And with dancing and music, we try to show our interior selves outside and melt together.

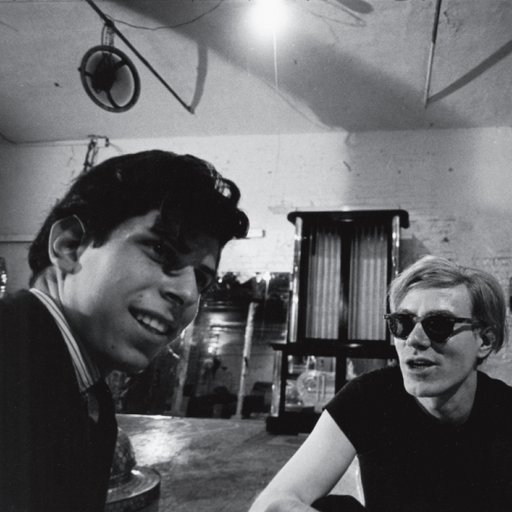

Were you aware of the work of musicians and artists who had tried to create similar situations in the past? The combination of music, film, and technology played an important role, particularly in the 1960s—I’m thinking of the whole Expanded Cinema phenomenon or even the more popular light shows of the Fillmore and of Warhol’sExploding Plastic Inevitable shows. Were you interested in these predecessors?

I only knew of those shows through photos and printed materials. But my siblings and I had seen a lot of music films, like the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, art directed by Heinz Edelmann, and Magical Mystery Tour and films about Bob Dylan. People tend to forget, but there was a music-film history long before MTV. Most of what I knew was through music films and TV. I hadn’t seen a music clip yet at that time, believe it or not.

What were the bands you were close to?

Oh, there were so many of them I heard on the radio or I kissed members of. We always had bands at home. There was a concert hall over the border in Lichtenstein, and the bands came from England and from all over Europe. They always slept at my mother’s house. My younger sisters listened more to new wave bands. I was a bit backward-looking—always ten years too late. I was consuming all the 1960s stuff. I was a big fan of John Lennon. The bands I liked had beautiful names: Orange Juice or the Television Personalities, for example. The Television Personalities slept at our house, and I really liked them. Their music was very ’60s but played in the ’80s.

The Television Personalities is also a good name and a good omen of what you would eventually end up doing.

Yes. When I was studying in Vienna, most of my friends were from Vorarlberg—the westernmost Austrian territory, close to Switzerland. They were Austrians, but they didn’t like Vienna, which they thought was too mainstream and centralized. And they didn’t feel drawn to Zurich or Munich. So they went directly to London or New York or other cities and brought back LPs to Vorarlberg, where you could hear great music and find great records in stores. Today it’s difficult to imagine, but in those times smaller centers could have very special scenes. In Vorarlberg there were different groups: some of my friends had rockabilly styling mixed with punk elements.

When would you say you made a video you realized was reaching beyond the world of music and was finally something you could call a video work or an artwork?

That happened only in ’86. During my first year of school in Basel, in video class, I submitted I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much (1986) to the Solothurn Film Festival. To be honest, when I sent it to the festival, I was just thinking, “Oh, I want to see what all the other filmmakers are doing….” I didn’t think so much of the video itself—I thought it was just a chance to attend the festival. Festivals were much more important then. There were no other possibilities to have access to recent video and film stuff.

So, I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much was accepted, much to my surprise. I showed it there. And I guess you can say it was well received, even though I still remember that when the film was projected, in the middle of it, the sound just went out. It was so badly made that I had half the sound on audio line A and the other half of the sound on audio line B. And they had only plugged in the A line, so halfway through, it went immediately silent, and I had to get up and do the sound myself, with my voice. But somehow people seemed to like it. There was a guy in the audience who invited me to show it as part of a program of video art in a museum—it was the Museum of Applied Arts in Basel, so not really a contemporary art museum. That must have been the first time I showed my work outside the music and cinema worlds.

I'm Not The Girl Who Misses Much, 1986 (stills)

I'm Not The Girl Who Misses Much, 1986 (stills)

Why do you think that particular video was so well received? What is in that work—and in many following ones—that connects so directly with the audience?

It did for sure strike a chord with people’s feelings. It’s hard to explain, but when people watch it they often say they can completely identify with it. Maybe it’s the quality of the image: it’s something that people think they could do themselves. And I guess it’s about an experience many know daily, this feeling of being like a puppet on strings.

I also think it had to do with what mass media were like at that precise moment in time. In Europe, and in Switzerland in particular, in the early 1980s, media and TV channels were still monopolies of the state—there was no such thing as private broadcasting or cable television. Even as other forms of mass media were becoming more and more dominant, they were still very much the voice of the state. But I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much feels very do-it-yourself: it looks like the audience is suddenly taking over the media, like a member of the audience is just making her own television broadcast. I think that’s why people relate to it. They felt that I symbolized the audience rather than the sender.

That’s quite interesting. The piece establishes an empathetic reaction because it gives the illusion that the girl in the video is one of us—is someone in the audience.

Yes, I think that’s part of the reason. There are many other examples in art history and video history in which the artist is in a room completely alone with a camera. And in many of these examples the content is shot in real time, and time is the subject itself—the fascination of playing with time is common in early video art. I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much instead is very edited: it feels like it’s real time, but it’s faster, it keeps cutting, it’s edited, even though there was no one else in the room—I started the camera myself and stopped it myself.

Unlike the work of many of your predecessors in the field of performance or video art, I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much is shot in color and with the vivid palette that would become your signature. So from this very first piece, there is a component of seduction and pleasure, which are crucial elements in many of your following works. If one thinks of the classic video art of the 1960s or 1970s—say, videos by Bruce Nauman and Vito Acconci, or the body art experiments—those works are usually black and white and quite punitive, in a sense. Instead, throughout your work one is faced with the idea that art can be pleasurable, that it can be seductive, even to the point of manipulation—and this is a question that also runs through the work of many other artists of your generation. When you filmed I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much, how conscious were you of the tradition of 1970s performance and video art, with its videos in real time?

I was conscious mainly of a few examples, like Bruce Nauman, Joan Jonas, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono, or Europeans like Ulrike Rosenbach and VALIE EXPORT.

But where do you think this devotion to pleasure that runs through your work came from? Were you reacting against 1970s performance video art? Or what else was inspiring you? You said that mass media were still very centralized in the 1980s, but that’s also when MTV began. Was this new type of television— that combined pleasure and entertainment—inspiring for you?

When I made I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much, I hadn’t seen MTV yet. I was referring to particular qualities I admired in TV, in live-music stage acts, and in social rituals. For me the idea of pleasure was coming from the wish to fill the whole TV program and all the rooms with it.

For a Swiss and a Protestant, this desire for pleasure is even more radical.

I had extreme antipathy toward religion, and I loved hysteria. I was trying to accept hysteria in myself and in others as a survival tactic. I wanted to be free to explode into pieces and not be ashamed of that. Exploding into pieces of pleasure.

[related-works-module]

How important is the word “girl” in that video? I think it’s particularly interesting to see your work within the tradition of feminist art. And the word “girl” in the 1990s gets charged with new connotations: think of the whole “riot grrrl” phenomenon or the “Bad Girls” exhibitions that took place pretty much simultaneously at the New Museum in New York, the Wright Art Gallery at UCLA in Los Angeles, and the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. Did you feel part of a tradition of feminist thinking when you made that work and some of your later ones?

Yes, for sure. When I went to high school, feminism was already something I was aware of and interested in. But it had started before—I was a boyish girl. When I was in primary school, I called myself Elisabeth John, and for one year I called myself Pierre. I tried to be a boy. I thought boys were freer, had more possibilities, more fun. I identified with the boys. Gradually, as I was becoming a young woman, I started to accept that I’m a female human, but even that took a while.

Until I was 30 or so, I felt more like a man in a girl’s body. It’s something I learned from the beginning. I was quite often mocked by all the boys in school. They would say, “You shouldn’t do that as a girl,” “You have too little breasts,” or whatever. So I learned very early on not to be impressed by what is allowed and what is prohibited, how I should behave. And when I started working, it was the same: I was very aware of what men did. For a while I was working in the chemical industry.

In which capacity?

As a computer-graphic designer. One of my teachers introduced me to Erhart Hauswirth, the head of the Ciba-Geigy chemical company’s video studio. They produced videos for promotional and educational purposes. When I worked there, we made films to train farmers how to use new fertilizers. I was the only woman on the team. And when they tried to tease me, I did not react. I tried to behave like a man. Whenever they gave me a new challenge, I always said I could do it. I saw that the other men pretended to know how to do things, and in the end they were able to do them, so I just copied their way of working.

At the time the processes were also completely different: it was very much one man to one machine. So if I wanted to learn how to handle a machine, I had to depend on a man. But the good thing about Ciba-Geigy was that Hauswirth supported me by allowing me to work there at night and to use the machines for my own work.

Do you think that your work as a commercial filmmaker influenced the way you approach your own work as an artist? Did it make you more expert at seducing the audience?

The relationship between advertising and art has always been very strong and works in both directions. There are great artists who of their own free will decide to remain rather anonymous in the commercial field because, perhaps, they are too afraid to stand by their work and be ridiculed for it, or the financial insecurity that comes with making art is not bearable. I could not live off my own art until after 1996. Sip My Ocean (1996) was the very first video installation that I sold: the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art bought it, and I was completely shocked. I simply couldn’t imagine that people would want to buy those things. Until then, I thought I had my day job and then there was my art.

Sip My Ocean, 1996 (still)

Sip My Ocean, 1996 (still)

Was there any film director or artist in either the commercial or the artistic field who was especially influential for you, particularly in the 1980s?

My biggest influences in the ’80s were my colleagues in Vienna, Bady Minck, Mara Mattuschka, Ansgar Schnitzer, Stefan Sagmeister, Wolfgang Capellari, and Andreas Holzknecht, and later in Basel, Käthe Walser, Gerda Steiner, Muda Mathis, and others.

And who were the artists you were measuring yourself up against, that you felt closer to, or that you thought were part of your art world?

I highly respected, for example, VALIE EXPORT and Yoko Ono. I was also a fan of Dieter Roth, Fischli and Weiss, and John Waters.

Both Pickelporno (Pimple Porno) (1992) and Sip My Ocean became rather famous outside the art world. Maybe because you were not exactly in the art world yourself or because those works are bigger than the art world. Was Pickelporno shown on TV?

Yes, in the Swiss experimental film program, which runs on TV in the middle of the night.

Had you made it for television?

No, but its origin was tied to television. Pickelporno came out of a very heated discussion in the media about pornography and feminism. Sometime in the 1990s pornography suddenly went viral, through VHS tapes and on private television channels. The use and consumption of porn completely changed—I know it’s hard to imagine now, but then it seemed like porn was all over the media. And there was quite a heated discussion, particularly among the feminists who wanted to stop pornography. And I didn’t like that idea. Or better, I didn’t like the idea that people would use so much power and anger to say what they did not like and what other people should not do.

I thought we should have used all that energy to say what we like, and so I decided to make a porn film for women or a porn film I would like. That was my proposition. My theory with this film was that women—and I am not even sure you can really generalize that broadly—may be more interested in knowing what the other is feeling and thinking than in seeing the action as a third person from the outside. When you watch sex from the outside, it is always much less interesting than when you are involved in it. So I wanted to make a porn film from the inside.

In this sense Pickelporno is one of your earlier works that makes very explicit one important theme in your oeuvre: the relationship between technology and bodies. One could say your work chronicles the way bodies change in relation to the various technologies of vision that are made available in the media.

Yes, if I look at the last 30 years or so of my work, I could describe it based on which technology was available for each project. For example, I used a surveillance camera for Pickelporno, a very small one that they called a “lipstick camera”—it was a Panasonic. It was made to be hidden in walls and made invisible: it had only a very small lens, which made it possible for me to go close to the skin without projecting any shadow. The camera had a rather wide angle with a big depth of field, so the closer you went, it could still keep the sharpness and the focus.

Pickelporno also established another important metaphor within your work, which is that the camera is a body in itself.

Exactly. In Pickelporno the human body—the carnal body—and the camera are on the same level, at the same height. The camera has no power above the object: the camera is not placed outside the action; it doesn’t have a presumed objective stance. Cameras and bodies are equal in this piece. That was always important for me; you should not be able to tell if the camera is filming the body or if the body is touching and filming the camera as well.

The combination of the organic and the technological is a fundamental theme in the history of art and cinema in the twentieth century. And more specifically, in the 1990s there was a resurgence of interest in some of these topics—think of the whole “post-human” debate that is still quite relevant today. Among the artists of your generation, you are one of the few who seems to describe this merging of the natural and the electronic with a certain enthusiasm. From your videos one gets the impression that the encounter between the flesh and the technological can be quite liberating and erotic. Your work is not only about the sex appeal of the inorganic, it’s also about the ecstasy of communication, if there is such a thing.

Yes, I think in my work there is a conscious approval of the potential of technical capabilities. I have a very sentimental relation to machines. I think that machines are like the testament of the people who invented them and developed them. I think the character of those people is preserved in the machines. So I try not to approach machines from a critical distance. On the contrary, I have always thought that if I can get close to them, I can melt together with them. If I treat them like another person, or like the echo of another person, then we can get along better.

Are you still optimistic about the technological transformations that you have witnessed and registered in your work? Now it is so common to criticize the digital industrial complex and the state of surveillance we live in.

Yes, I am still optimistic, but probably now I am more consciously so: I am working to be optimistic. As you get older your perception of the world is tinted by the fact that you know more clearly that you will die. Statistically, young people are more optimistic than older people. As I get older, I cannot separate my own fate from my own opinion. So now I have a responsibility to be more optimistic.

When we worked together on your exhibition in Milan (“Worry Will Vanish,” Hauser & Wirth, 2014), which was installed in an old, beautiful abandoned cinema from the 1950s, I remember you spoke about these types of spaces and the technology of cinema—particularly of CinemaScope—with a sense of nostalgia. The exhibition had a melancholic character to it: it was like visiting an old amusement park.

In Milan many locals told me about their memories of their first cinema visit, which made me think that in the last few years we have witnessed a very dramatic change in how we relate to images. The experience of the moving image has progressively migrated from a communal consumption on big screens to an individual, lonely consumption on smaller and smaller screens. But luckily this change has corresponded to an explosion of different possible points of view: power is no longer concentrated in one medium or on one screen; it can be distributed among many different subjects who are not only receiving images but also producing them.

Simultaneously, I still believe in installation works as places for communal gatherings, where single humans are joined in a communion that is greater than the sum of its parts—a space where a melting of knowledge and feelings occurs, creating a common thought or a giant speech bubble. Tyngdkraft, var min vän (Gravity, Be My Friend) (2007), Homo Sapiens Sapiens (2005), and the new work on the fourth floor of the New Museum represent such an analogy. In the last few years my work has become more architectural or larger in scale, but what I think has actually happened is that the work is dissolving the architecture. The projections now fit exactly in the exhibition spaces, taking over entire volumes and walls, and they dematerialize ceilings and walls, opening them up, liquefying them with images.

In your work there is often a sense of blissful abandonment, of letting go and losing oneself in technology, of dissolving oneself in the ocean of images. And that’s exactly what we are taught in schools and universities is the ultimate evil—the passive acceptance of the spectacle. For many of your contemporaries in the VCR generation—and I am thinking of your peers such as Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Douglas Gordon, Steve McQueen, and many others—the question of how to deal with the spectacle of the moving image and of technology has been a crucial dilemma, and one could describe the art of the 1990s and the beginning of this century as the attempt to come to terms with the spectacle of technology. Some might say you are more complicit with the numbing power of technology, but on the other hand I find your position more complicated than those of some of your peers, who can be quite moralistic.

I’m also moralistic, but sometimes I think that it is also important to be moralistic against the excesses of moralism. And I’m not afraid of being accused of being complicit with technology, as I think that what really matters is who retains the power and for which goals technology is implemented. Simply trying to turn your back on the spectacle is as reactionary as the spectacle itself. I feel that electronic art exists at the intersection of information technology, neuroscience, biotechnology, and nanotechnology—and not only do I profit from their developments, I am also caught in the contradictions that go hand in hand with these developments in which we are all implicated. I believe in the technological sublime. And the potential for terror has been a part of the sentiment of the sublime since back in the days of Romantic painting, when it was mostly associated with the power of nature.

Homo Sapiens Sapiens, 2005. Installation view: “The World Is Yours: Pipilotti Rist – Homo Sapiens Sapiens,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, 2010

Homo Sapiens Sapiens, 2005. Installation view: “The World Is Yours: Pipilotti Rist – Homo Sapiens Sapiens,” Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, 2010

I think ultimately it has to do with how you imagine your viewers and how you treat them, if you are empowering your audience. What do you want them to do with your work? How do you want them to be in your work?

I want them to spit onto their mobiles so that they can see through their saliva how the pixels are fragmented and understand how the technology is composed. I want them not to be afraid of technology, and I want them to break away from the idea of the screen as a square, a cage. I think there are different forms of empowerment, and I want to give them power, but on their terms. With my exhibitions I want to provide a stage and let the visitors become the actors. Oftentimes I only slightly change their body positions, free them of the permanent fight against gravity, or invite them to take their shoes off or hide their bodies in front of the other visitors. Such fine alterations have enormous influences on our capacity for contemplation.

You often speak about technology in almost organic, even animistic, terms.

Yes, because I think that technology, especially audio and video technology, is a complete copy of our senses. For example, the RGB system tries to replicate how the cones and sticks in our eyes work: it’s a very primitive copy of the eye, and I feel sympathy for it. It’s only mass production that makes technology look like plastic, metal, and cables. Cameras and projectors look like anti-bodies, but they are actually complete copies of the body. Instead, people tend to have a misplaced fear of or respect toward technology. I like how younger people use machines much more spontaneously.

Maybe that’s why your work has become progressively more and more optimistic. In video works from the 1970s, the bodies are often suffering or carrying out painful, repetitive gestures. In your work, by contrast, bodies seem to be enveloped in pleasure.

I am not so sure, actually. There are many suffering bodies in my work, like in Selbstos im Lavabad (Selfless In The Bath Of Lava) (1994). Maybe what has changed is that the viewer is no longer consuming the body of the artist: it’s the artist that somehow is consuming the viewer. The floor projection Mutaflor (1996) deals with this idea quite literally by letting the object of the viewers’ gaze swallow the camera. I have experimented with this inversion of the gaze in many other works for which I have researched image-producing technologies in the medical field, such as MRI and endoscopic and microscopic cameras. These tools are usually used to search for aberrations and diseases, and instead I have tried to adapt them to find deeper revelations. I have always been convinced that we can find philosophical truth in the organic substance of the body, which also includes our amphibian brain. A nice example of this correspondence is the image of the double snakes that appeared in many cults long before the DNA double helix was discovered.

Speaking of snakes, I have always thought of your work as being quite Edenic, as though you are trying to imagine a technological paradise. Maybe that’s the sense of communion your work can generate—it’s like a cathodic church.

Selbstlosim Lavabad is actually set in purgatory. Other works, like Homo Sapiens Sapiens, are more positive, but that’s because I was trying to imagine a world where the fall of man had never happened.

Would you say your work is about imagining these utopian places? Are they about how the world should or could be?

Of course, yes, in my work I imagine a lot of new possible ways of being: I imagine that life would be better if we didn’t have only two genders, but perhaps twenty different ones, so that they wouldn’t be so important or the source of so much pain. I imagine that women could have the same space and authority as men. I imagine women as Vitruvian men: I imagine that they can be themselves and also represent humanity. And I think my work is an attempt at making visible the way we feel and exist within ourselves. For example, I think somehow Pixelwald (Pixel Forest) (2016)—the new piece that was shown in Zurich and will be presented at the New Museum— replicates the way in which our synapses work; my work often takes the inside outside and vice versa.

Lungenflügel (Lobe of the Lung), 2009 (stills)

Lungenflügel (Lobe of the Lung), 2009 (stills)

It takes the idea of Expanded Cinema even further: cinema always happened in the head of the viewer, but here there is almost no screen—it’s immaterial. I am reminded of a quote by film theorist Christian Metz, who described cinema as “a shared state of amorous passion” and “the temporary breaking of a very normal solitude.” He thought that the magic of cinema had to do with seeing images in front of our eyes that resembled the kinds of images we usually see in our dreams, with our eyes closed. The stupor of cinema derives from seeing in reality and together with other people images that are similar to what we have experienced in solitude in our dreams and realizing that those images are at the same time possible and impossible. Metz speaks about this realization coming with a sense of mild despair. It is such a touching way to describe what cinema does to us. It’s like seeing your interior images be given physical form.

Such topics interest me, too. The free-hanging pixels of Pixelwald not only resemble the oxygen bubbles emitted by sea grass but also try to reconcile the different qualities of light we are exposed to—artificial lights, warm lights, big bulbs, the cooler light of the many screens around and mostly in front of us, the imaginable sparks in the synaptic clefts where nerve cells pass via an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron, and finally the sunlight in its different temperatures according to the time and one’s position on the planet.

With Pixelwald I wanted to try to bring these dimensions together by making them apparent and visible. I wanted to play with them and explode the flatness of the screens into space and let people wander through the pixels, as though they could wander through a brain. I think the response of the audience is quite overwhelming, which proves that the pixel forest somehow strikes inner and outer strings.

What do you think you or your art want to do to the viewer? I don’t want to sound too hippieish, but there is always a soothing quality to your work.

I’m totally fine with being a hippie. I am Pipi. And I’m not afraid of the idea that art can heal. That’s what I expect from art—both my own and work by other artists. I want art to be consoling or at least to bring some kind of enlarged logic to the way we are. We are surrounded by so many humming sounds, cables, and things going “zzzzz”—electronic devices, and air-conditioning, and cars, and all this stuff that apparently makes too little sense and makes noise. Like with a homeopathic remedy, for you to heal, you need the same thing that makes you crazy. That’s what I am trying to do.

[related-works-module]