When a Damien Hirst retrospective opened at the Tate Modern last year, it became clear that the foremost YBA is today’s most loved and loathed artist. British critic Julian Spalding put it bluntly when he wrote, “Damien Hirst is not an artist.” (Spalding was then banned from visiting the exhibition.) Even organizations that normally have no interest in art began to heap on the hatred—PETA, for example, called Hirst’s art “callous” after 9,000 butterflies were killed for a work in the retrospective. But all of this did little to stop the public from flocking to the show, which broke the institution's attendance records.

To be so hated and adored at just 42 years old is no easy feat, yet Hirst has flawlessly cemented this reputation. His career has been controversial and tumultuous, beginning with the opening of his infamous 1988 exhibition “Freeze,” which grouped the YBAs together for the first time. A slew of dead animals, an off-color comment about 9/11, a Turner Prize, and more than 80 solo shows later, Hirst has provoked and prodded his way to fame (and considerable fortune).

See why Hirst has been said to “uncannily touch the nerve of our time,” in the words of art historian Rudi Fuchs, in this tour of the artist’s greatest themes.

SHOCK

“Great art is when you just walk around a corner and go, ‘Fucking hell! What’s that!’” Hirst once said, and, sure enough, shock is perhaps the most notable attribute of his work. It’s certainly the feeling evoked by works in the “Natural History” series, for which Hirst injected dead animals with formaldehyde and enclosed them in glass cases. Works like The Golden Calf, a baby cow adorned with gold that references the Biblical statue from the book of Exodus, confront the viewer with surreal, disturbing imagery that feels almost as if it were engineered to provoke a reaction.

MONEY

Sometimes the monetary value of Hirst’s work can be as jarring as his subject matter. In 2007, For the Love of God, a platinum cast of a 300-year-old skull encrusted with 1,106.8 carats worth of diamonds, sold for £50 million, or about $100 million (albeit to a consortium of buyers that included Hirst himself.) The pricy sculpture is just as much a memento mori as it is a statement about dying to make money. Death is forever, money is not, and yet perhaps some of those who mined Hirst’s diamonds died for their products anyway. In conceiving the work, Hirst has said that he thought to himself, “What can you pit against death?” Money, apparently.

DEATH

Although For the Love of God and The Golden Calf both appear to be works about immortality, they are actually more about the inevitability of death. Death, as Hirst repeatedly makes clear, is permanent—“I am going to die and I want to live forever,” he said in an interview with artist Sophie Calle. If Hirst can’t live forever, perhaps his work can. The animals of the “Natural History” series are permanently preserved in their current state by the formaldehyde, even if they will never live again, suspended in a state somewhere between life and death.

RESURRECTION

Modern science may fail to enable immortality, but nature continues on on its own terms in Hirst’s art. As such, the natural world seems capable of perpetuating and resurrecting itself. Hirst’s visual symbol for resurrection is the butterfly, which symbolizes rebirth in Christian iconography and the soul in Greek mythology. Hirst has executed several series involving butterflies, including one in which he coated them in house paint and organized them into patterns that resembled stained-glass windows. For another, he trapped butterflies in the wet paint of monochromes. In both cases, the butterflies died but appeared very much alive.

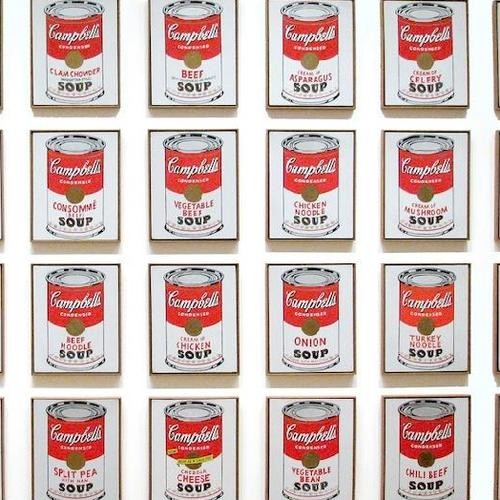

COLOR

Aside from his metaphysical interests, Hirst is also concerned with the formal qualities of art. His spot paintings, a colorful series of experiments in which he paints circles onto white canvases, explore the relationships between colors. The series may have a cold, mechanical feel (the dots appear absent of a human touch), but even this aspect of his practice inevitably produces a response. “It’s an amazing fact that all objects leap beyond their own dimension,” said Hirst once in an interview about the spot paintings.

CATHARSIS

Damien Hirst’s work seems cynical. It belabors death’s permanence, the rule of money, and the insufficiency of science. But despite the pretense and dispassionate subtext if Hirst’s work, there always remains a certain sense of hope. Art critic and philosopher Arthur C. Danto has called Hirst’s “Medicine Cabinets” series, in which the artist lines the bathroom fixtures with pill bottles, a “beautiful metaphor for a society worth living in,” one in which art can heal—or at least help. When asked once if he could make art capable of aiding society, Hirst said no, but added, “I’m not going to stop trying.”