There are two shows currently taking place in New York that regard Obama as a touchstone. The first is Michelle Grabner’s festive floor at the Whitney Biennial, where the president stares with distinguished self-possession into the lens of photographer Daywoud Bey. Young and commanding, this is Obama before the announcement of his candidacy in 2008. The moment marks a progressive direction forward for the country, and, serving as a mantle above Grabner's curatorial text, for American art today.

But just as the presence of a black president in the White House hasn't ushered in an era of racial comity in America, Obama's cameo in the Biennial doesn't mean that the art world is a place of utopian equality. This tension was brought to light recently by the Yams collective, which withdrew from the Biennial in protest of the inclusion of work by Joe Scanlan, a Princeton professor who submitted work fictitiously created by a black female artist named Donelle Woolford—a hornet's nest of racial and gender-based provocation.

Downtown, another showcalled“Black Eye”at 57 Walker Street curated by Nicola Vassell, the previous director of both Pace Gallery and Deitch Projects, also evokes the age of Obama. But unlike Grabner, Vassell is not tapping into the dewy optimism that accompanied Obama's first inauguration. Instead, she cites his sobering reelection in 2012 as the show’s genesis: the second time around, she recalls, there was still pride, but also a diminishment of expectations. The crush of the political system in Washington had stamped out the nation’s sense of unfettered possibility.

Vassell has an uncanny knack for identifying moments of collective experience like this—moments of political breakdown that, at times, can crystalize into artistic opportunities. In 2008, she put on the charged exhibition “Substraction” at Deitch Project, which bottled the wild energy of a group of hardscrabbledowntown kids in the post-9/11 era, when the very infrastructures of New York—and on their canvases—no longer seemed secure.

Today, the instability that Vassell is exploring has to do with archaic notions of authenticity and race. On the May afternoon, sitting on the stoop outside of the gallery, the curator dragged on a cigarette and asked abstractly, “What are the shadows that lurk against the hard structures, the shadows that complete the picture more powerfully than the structure itself?” We might imagine that the artists at "Black Eye" form those defining outlines, contrasting the traditional art-world structures. Here’s a look at a few of their works.

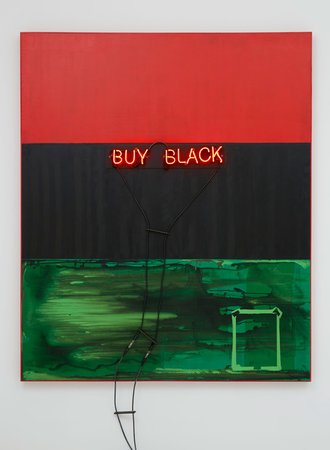

MESSIER MODERNISM

Opening the show is this giant neon-lit canvas by Kerry James Marshall, an artist born in 1955 Birmingham. Marshall doesn’t shirk the social obligation inscribed in the circumstances of his birth. Like many of the other artists in the show, he hybridizes traditions. This work, part of a series called “Who’s Afraid of Red, Black, and Green,” reworks Barnett Newman’s Minimalist painting Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue with the colors of the Pan-African flag. The signage "Buy Black," Vassell explains, refers to those once hung in the windows of black-owned businesses in the Civil Rights-era South. As such, Marshall injects Modernism's safe, sublime swaths of color with political meaning.

BLURRED LINES

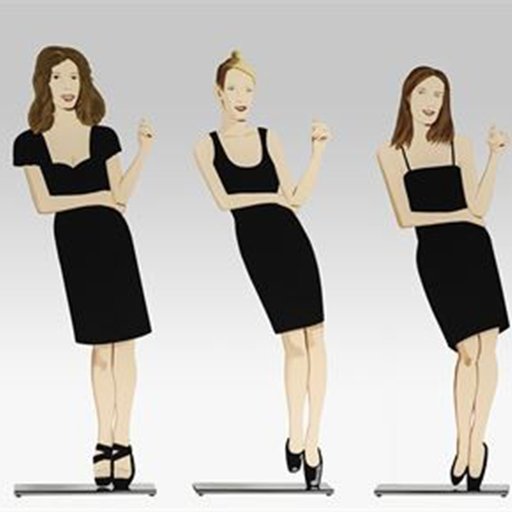

“You see what’s obvious here—you see the story we are trying to tell with this show,” Vassell said. The work like this one by Hank Willis Thomas demonstrates how in talking about race, artists tend to dismantle it as a category. Thomas’s hologram contains two messages, seen, as Vassell demonstrated, pacing in front of it. In one direction it reads: “Black imitates white.” In the other direction, “White imitates black.” Thomas explains in a video online, “What I know about myself has been taught to me by people who identify specifically as white.” The categories are literally blurred when the visitor is in motion.

BODIES AND BRAIDS

There are a number of artists in the show who question standards of beauty. The masterful draftswoman Toyin Odutola renders a “21st-century girl looking fly,” Vassell says, with the subject's skin rendered with dense, knotted braids. Nearby, in the photograph by Deana Lawson, skin, in all its gorgeousness, is on full display as three women from New Orleans lean naked into one another, perhaps evoking the Three Graces, Vassel suggested. Towards the back of the hall, the oil painting by Lynette Yiadom Boakye pictures a beautiful jester-like figure with a fringed collar whose gender, Vassell pointed out, is unclear. Across the hall, vulnerability is discarded: Kehinde Wiley's giant canvas pictures a black Judith triumphantly beheading a blonde female Holofernes. “There is a guilty pleasure,” Vassell admits. Beauty is a power that is wielded by these subjects, sometimes with with knife-thrusting force.

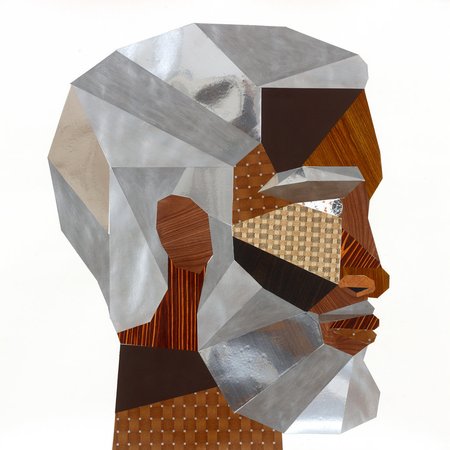

FRACTURED SELVES

The many selves in the show are also often fragmented. Derek Adams makes geometric puzzle-piece collages with different patterned papers: textured like wood, lattice, and metal. But, Vassell pointed out, their textures are illusions; the material is still paper. Meanwhile, Xaviera Simmons in the back of the exhibition photographs living sculptures: individuals with tiny souvenirs and occult symbols dangling on them, the many disparate objects that populate memory and lived experience. Vassell calls them “pegs of experience that one attaches to oneself,” and considers it part of the millenial mentality, crafting a whole identity from many different unrelated pieces.

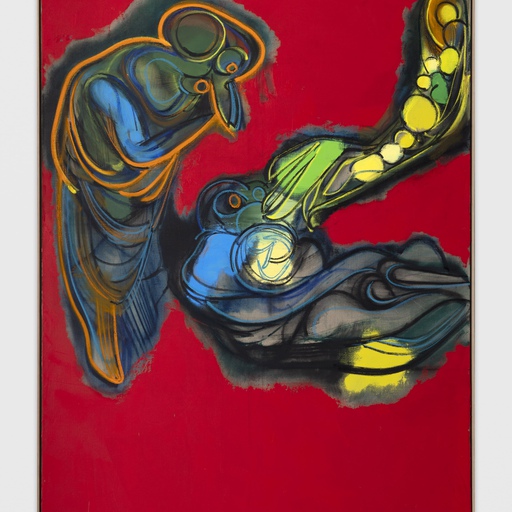

BAROQUE TO BLING

So, why does the art world stay so white? “Art requires patronage, it requires excess capital, it requires a leisure mentality, and luxury, and none of those things belong to the people who have not,” Vassell said. Artist Rashaad Newsome captures this observation through the bling of this layered, rotary piece, ornamented with little black putti. “You see the diamond rings, the hubcap, the gold. And a heart beat away? The cross-section of a Roman Catholic cathedral, the rim of heaven infinity,” Vassell said. You have to wonder about the cozy, congruous relationship between these structures: who gets to access to art, who defines taste, and, by contrast, who doesn’t.