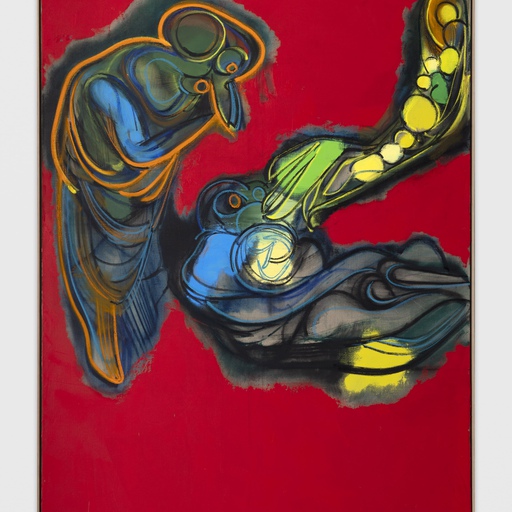

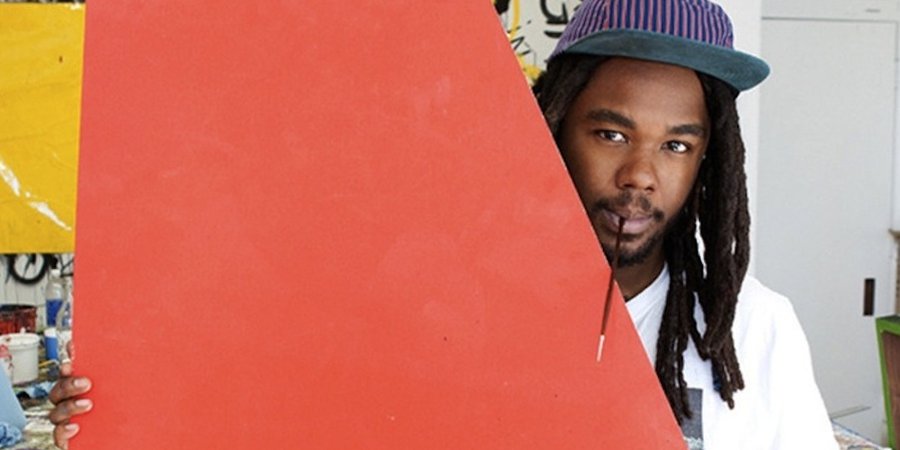

What does the song "Hey Soul Sister," Matisse, NBA players, National Geographic spreads, disco, baby daddies, and the candy piles of Felix Gonzales-Torres have in common? They are all flotsam from the cultural tides that Devin Troy Strother, a self-described product of the 1990s TV generation, nets in his intricate and often provocative collaged paintings. Into this already potent—and downright hilarious—satirical farrago, the 28-year-old California-born and Brooklyn-based artist also adds his signature characters—impish, jet-black figures with the exaggerated facial expressions of minstrelsy.

Strother talked with Artspace about injecting humor into the buttoned-up art world, and why he thinks Michael Jordan and Gerhard Richter belong in the same conversation.

Black characters—or figures in blackface, it's never completely clear—have become your calling card, but you once said that you didn’t start painting black skin until the last year at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena because you found it more technically difficult to represent. Can you talk about how you came to your characters?

There was a teacher who once asked me why I didn’t draw black people. I was like, “Should I?” I told him the whole thing about how they’re more difficult, you know, the highlights are all backwards and the shadows are all funny to me. And he was like, “You know if it’s something that’s hard for you to do, you should probably try to do it a little bit more.” That’s the basic thing that made me think about doing black people. Usually most black artists are concerned with themes that have to do with black people, and I really didn’t want to do that in the beginning.

Your Lilliputian figures are quite distinctive—where did they come from?

I used to really be into East Indian miniature paintings, actually. And when I was about to graduate, I didn’t really have anything too concrete that I liked. So out of frustration, I thought, “Well, I’m just going to copy one of these little East Indian miniature paintings,” and I copied one with all these figures around an altar. I painted their heads and hands blank, and I didn't know if I should make them brown like the Indian people, and I didn't really want to make them white, because I always painted white people. So I decided to paint them all black.

In the first four paintings, the figures didn't have faces—they were just black figures, almost like a Kerry James Marshall painting. But I looked at them and thought, “Fuck, this looks too much like this person, this looks too much like this person.” Everyone’s got their own black figure, and I was like, “If I’m going to be painting black people, I got to have my signature." I’ve got to have my black guy, you know? [Laughs]

So I was like, “Well, how do you represent a black person?” I was thinking like a designer, like if I was just trying to convey what a black person is to someone who has never seen a black person and using just straight, regular primary colors. What would you use? So I gave them black for the face, white for the eyes and for the teeth, and then red lips, just because red stands out really well against black, and then I gave them little light-blue eyes because I didn’t want them to have black eyes.

So the working palette was red, white, and blue?

Yeah, I was like, "That works—these are African Americans."

In the past, you’ve made it sound like the fact that these figures are black is almost incidental. How do issues of race play into your work?

A lot of my work is trying to move away from a very heavy-handed commentary on race. I want to sway that conversation, you know? That’s why I try to reference the NBA and contemporary art in the same moment by juxtaposing Michael Jordan and Gerhard Richter. I guess you can say it’s a black thing, but I think it’s more about social status. Really, a lot of it is just shit that makes me laugh, and that’s what I think a big part of my practice is—it’s funny. It’s talking about race, but it’s not talking about it directly, with anything being anyone’s fault or that we’re in a certain situation because of it. It’s more, “Yeah, there's a thing about race, and we all acknowledge that, and this work kind of has to do with race, but we can all get past that very quickly.”

I think that’s why I try to go into so many different subjects, because the art is expanding—it’s not just Kara Walker talking about the 1800s and shit like that. I’m not trying to talk about a bunch of shit that other people have already talked about. You know what I mean? Like we all know slavery happened, we all know that civil rights happened, we all know that shit was fucked up.

It’s pretty privileged to be able to just say, “Yeah, these things happened in history”—and it's not the stance that many artists have taken over the past few decades. Your wanting to be more expansive as an artist seems like a distinctly millennial perspective.

Being born in 1986, I was a kid in the ’90s. I went to a lot of private schools, so there was usually me and maybe one other black kid. A lot of times I was the only black kid in class, and it was really cool to be the only black kid in class, because I was the fucking only black kid in the class, you know? I was always the cool kid at every school I went to because I was the only black kid.

What about in the art world?

No, there are a handful of black kids like Lucien Smith, Oscar Murillo, Jacolby Satterwhite, Jayson Musson, and we’re all the same generation, basically—a generation raised off television in an era when it was cool to be black. There was a transition in that era, I feel, when black people could be hugely successful without being a rapper or playing basketball. You could be something else too. I credit Pharell Williams all the time, but he's actually one of the first black people who was nationally known to be alternative and shit like that. Pharrell is a little bit different. Of that generation, he broke a lot of boundaries.

The titles you give your work, which often incorporate phrases you overhear on the street, are arresting—like Ohhh, that's just my gurrrl Sha'luanda, or Those Two Bitches Nashawna and Shamecca Are Late For the Lynda Benglis Shit, or Six Black John Baldessaris Water the Plants, While Six Niggas Build A Triangle and a Bunch of Other Niggas Watch. You’ve said before that some people may be buying your works just because of the funny titles. Can you talk about these a bit?

I went to school for illustration, and a lot of illustration is basically trying to translate text into an image or trying to make an image suit a piece of text. So, basically, it's about trying to put a whole paragraph into a single image. I don’t think I’m always successful at doing that, but that’s what I try to do.

You keep a notebook where you jot down parts of conversation. Do the images or the words come first to you?

It goes both ways. Sometimes the image comes and then the title comes right away, and sometimes it’s a title and then the image comes right away too.

You’ve called the figures on your canvases "cultural stand-ins." What are they stand-ins for?

I guess they are cultural stand-ins for culture really. They are cultural stand-ins for how I see what people are now. I hang out with a lot of people who aren’t black and, by the way that a lot of them talk and act, you would think that they grew up with a lot of black people, even though a lot of them didn’t. They’ve adopted a certain way of talking. You know, everyone I know listens to rap music very avidly, and most of them aren’t black. I have white friends who are blacker than I am. [Laughs] I grew up in the suburbs. I grew up skateboarding and shit. I didn’t grow up around a lot of black people—I grew up around mainly Hispanics and Asian people.

Formally, some of the figures remind me of the sculptures that inspired the pictorial flatness and fragmented planes Modern masters like Picasso, Matisse, and Cézanne. You also riff often on Modernism and post-Modernism. What’s your interest in repurposing these canonical tropes?

It’s more an interest in referencing a kind of art that’s made for art history in a weird way, that incorporates elements that are so commonly used to show you that something's art. There are the popular examples you see, like when something looks like someone looked up what installation art is and then started going off of those tropes. The second you look up performance art, Marina Abramović is going to pop up as the first name you see. It’s more of my interest in the Internet and Google, what the standard is for things that the world picks as art.