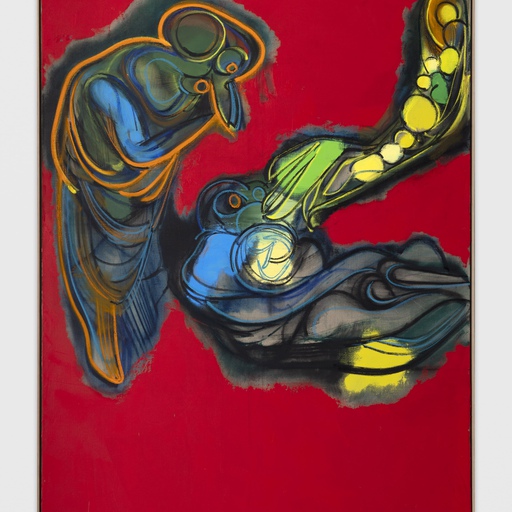

For a while now Amy Sillman has been one of the most exciting painters working in America, creating bravura canvases that poke fun at the orthodox distinctions between figuration and abstraction, messing it all together into a humorous, thought-provoking, and often sexy stew. Now she is included in the Whitney Biennial (her second) in a year that also sees her acclaimed survey "Amy Sillman: One Lump or Two" touring in May to Bard College's Center for Curatorial Studies, where she is the co-chair of the influential paintings department (and where she herself earned her MFA in 1995).

With painting having an undeniable moment now—painters make up about a third of the artists in the Biennial—Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Sillman about her work, her addiction to improv comedy, and whether artists still need to go to grad school or not.

What are you presenting in the Biennial?

I'm going to have one painting in the show and then there's also a collaborative piece that I did with my friend Pam Lins, who is a sculptor—it's a collaborative sort of painting-sculpture. The painting is completely abstract and the sculpture is… well, I don’t know what you'd call it. It has ceramic objects in it and those have holes in them, so you could call them jars. But the form is abstract. And the painting and the sculpture have a relationship with each other, a friendly relationship.

Do you often make collaborative works like this?

I've done a ton of collaborations actually, but I've never collaborated with a sculptor, and I've never collaborated with Pam, and I've never collaborated and then shown the work in a big show.

In the catalogue for your show, the curator Helen Molesworth states: "painting is perhaps more influential and vital today than anytime since the heyday of the New York School in the late '40s and early '50s." How did that happen?

I'm probably not the person who knows! [Laughs] For me painting was always what I was busy doing—though I kind of think that I'm actually more of a drawer than a painter, in a way. But I don’t know. It's a really good question that I actually and honestly don’t have the answer to, and I don’t know why.

How did you become a painter in the first place? You started in a period when painting was a fairly unfashionable position to take as an artist, and looking back at the Abstract Expressionist legacy—as you did—was even more unfashionable. How did that organically come about for you?

That's not the way it felt to me, entirely—that there wasn’t painting and then, all of a sudden, there was painting. Because I went to art school and, of course, there were painters and painting teachers at the same time as there were people who weren’t painters and who were critiquing painting very strongly. But the antagonism then between anti-painting people and pro-painting people is not a fiction—it was very profound. But I think that when you are going to art school you just know a lot of people who do traditional things for different reasons or in a different spirit than they were done originally, but who are still interested in those forms.

So my interest in painting was partly that it was for me indistinguishable from drawing—I didn’t really make a distinction rhetorically between the forms. And while there was a critique of painting, there wasn’t a critique of drawing, so I was drawing a lot and taking a subtler approach to thinking about what was underneath all these things. But for a long time I didn’t know many other painters, because I went to a school where there was always a very conceptual way of thinking. But, you know, people are always doing everything.

Even though there were several women artists who were working very productively in postwar Abstract Expressionism, that artistic period has long been primarily associated with a very male brand of dramatically heroic gestural painting. Was this something that you were at all engaging with at the time?

You mean the masculinism? No. I mean, it was very clear to me that the people who had an articulate critique of painting were conscious of the traditions of machismo, and in a way I was aligned with those critics, but then on the other hand I do like an aspect of gestural painting, so there's something in it for me that that critique misses. So, you know it's there, but at the same time you have to ignore a certain part of that rhetoric. There's the part of painting that is just an activity, and if you like paint or color or gesture or drawing or a certain kind of surface, you're going to end up making paintings—and then you're just going to have to grapple with the structures around that. As I got older and I started reading more, I began to understand why it was really important to have a critical discourse. But it didn’t mean that I shouldn’t do something—it just meant that I had a much more nuanced way of thinking about it.

One of your major contributions to painting is your continual refusal to admit the separation of abstraction and figuration, embedding people-like shapes doing hazily recognizable things in paintings that otherwise look like the gestural abstractions of de Kooning or Diebenkorn. How did these figures start creeping into your compositions?

Well, when I was going to school you had to declare an allegiance to a form and an attitude towards abstraction, and from the get-go I wasn’t going to declare an allegiance. Perhaps I just had a contradictory way of thinking, but it was useful for me to have the figure come and go, let's say—for the figure to be able to flicker in and then be dismissed. Painting is real close to the bone, and people do what they do. But there are certainly other artists who have similar approaches, and one of them is Dona Nelson, who's also in the Biennial and whose work I have known forever. At times her work has been figurative and at times completely abstract; at times it's been totally about a picture, and other times there's been no picture, just pure abstraction or pure process. I don’t know how she thinks about it, but I know that in her work there are these sorts of modalities. And it doesn’t define the work really—it's more just how a specific painting is organized. I don’t know if those terms of abstraction or figuration are even useful to her. She's very free-floating, and she pretty much does what she needs to do, or follows what she needs to follow.

A famous series of yours began with you creating drawings of couples in your circle, then redrawing them from memory in your studio, and then painting abstractions inspired by their poses. In these, the figures have pretty much entirely dissolved as far as the viewer is concerned, and can only be intuited if they are told to look for it. Is it enough that you know figuration is in there? What were you exploring with these?

I don’t expect anyone to see those figures—I don’t know how you could see those figures if you didn’t have a way of tracking the genealogy of the shapes. One of things that's interesting about having a survey show is that it attempts to clarify some things in the work, and the relationship between these works is something that only became clear in the show, but we didn't do it in a pedagogic way—we didn’t say, "Here's step one where it looks like a figure, here's step two where it looks abstract-y, and here's step three where it is purely abstract." But by now, because of catalogues and gallery talks, people have learned about the process behind these works. But I certainly didn’t expect anyone to look at the abstract paintings and say, “Look, here are those people," or, "That's a leg over there.” I didn’t really care—that wasn’t the goal.

The goal was to understand how a form was working in drawings and not to derive it from the world of imagination but rather to sort of start with something you can see, and then mutate it or transform it further. Surprisingly, what I ended up finding out was that even if the forms came from something, they ended up weirdly looking like the abstract paintings that I had done before I started looking at things. So I realized that, of course, all my abstract paintings are based off something that I've seen in the world and that my brain has abstracted. Every shape has some kind of referent, so you are making something out of something, even if it is a kind of very distilled reference.

How do you go about generating a new painting? I know some painters set out thinking about a problem that they're looking to investigate.

Well, the quote-unquote “problem” is simply to turn the last body of work upside down in some way. That's always the problem—to take the given and run with it, and the given is usually what you did last time. So it's very easy, in a way, because you can think, “Okay, I was drawing stick figures before—now I'll make figures that are based on actually looking at people." Then, "Okay, I was looking at people. This time I won’t even look at people." Then, "Okay, now I'll look at something but it won’t be a person.” It's always easy like that, because you're restless to do something different than you did last time.

Is drawing always part of the process for your paintings?

Not necessarily as a preparatory thing, but I'm always drawing. Drawing is easier than painting, I think—you just sit down and do it. With painting, you have to think about what to get to make the work. You've got to go out and buy more stuff.

You have also long created incredibly funny cartoons, which range from New Yorker-style gags to mordant satires of the art world in the cases of your MoMA drawings and seating charts, which place different art-world types around a table and eviscerate each one. How did these cartoons start?

I was just feeling so lonely! [Laughs] I mean, all comedy comes from misery. For a while I was living in Germany and didn't know anybody, so the seating charts came from when I'd get invited to a dinner and then go home at night and remember everybody who was there. Basically, they were made to make my friends back home laugh.

You're very talented at comedy, which is not something one expects from painters.

I'm a complete comedy junky. I go all the time to comedy clubs, I watch comedy obsessively, and I read about it because I'm actually really interested in how it works. I desperately want to take an improv class at the Upright Citizens Brigade, because I think it would be really amazing to try to do something where you don’t have a pencil and it's just you. I don’t think I would be good at it, but I'm really interested in trying. I don’t think it would be that different from painting, in a way, because you really have to make it up as you go along.

I mean, Performa is two years away….

[Laugh] I don’t have the nerve.

How does this comedy aspect relate to the paintings? Can abstract paintings be funny?

I always drew funny drawings, but I never thought about putting them in my painting shows until later in the game, and that was a big break for me. I had a show in 2005 where I pinned comedic drawings to the wall throughout where the paintings were hung—it was called “The Other One,” and I specifically thought that the comedic drawings were the “other one” to the abstract paintings. I think it was an actually really good show, then later the idea developed more and more. But I was always really interested in drawing funny pictures or cute pictures. I like to draw cute dogs and stuff, and I'm very proud of my ability as a cuteness drawer. So I'd try to draw things that were inappropriate, not in that they were ugly or racy or anything, just inappropriately cute or funny, showing emotions that you're not suppose to have if you are a serious person. Then I'd try to amuse myself or my friends with them, and it kind of crept into my paintings.

You've also said that your work is "always psychological" with the shapes "troubled in a way" or "abject"—can you talk about this a bit?

That's the flip-side of the coin of funny. And I'm a Jew—I'm the ultimate Jewish artist. That's like having a mainline to the funny and sad.

Your paintings seem to probe these kinds of binaries deeply, and you're obviously drawn to philosophy, with your cartoons expressing a wide-ranging familiarity with many theorists. The ambivalence in your work also makes one think of Wittgenstein's ideas about language games and picture theory.

Well, it's all about wanting to experience things that you are curious about. I think the way that people express their vitality is through their curiosity, and I guess I'm just actively curious about things that I don’t understand, including painting. It goes back to when I was a kid and really interested in things that I didn't understand. I didn’t understand painting, I didn’t understand language, I didn’t understand philosophy, I didn't understand academic things, like psychoanalytic theory, et cetera. And so then I would learn about everything. I really am just a complete nerd, and I like to structure my life in terms of semesters—like, this semester in life I'm taking a class in comedy writing and animation; last semester I was taking philosophy and cooking. I think everyone I know is always trying to figure out a few things too, and that sort of somehow gets into my work.

As a highly influential painting teacher at Bard, you're clearly invested in more tradition forms of education too. Do you think artists should always go to graduate school?

You know, I there's a new book coming out called Should I Go to Grad School? and they asked me to write an essay for the art section. I basically said that, for me, grad school was great and a really salutary and productive open space—I was really into it, and I'm glad I went, and I'm glad that I teach at one now. A while ago I was talking to a young friend who hadn’t gone to grad school, and I was saying to her, “You should go to grad school.” She said, “Why would I need to go to grad school? I live in New York, I'm meeting people, I'm doing a show.” And I said, “Are you kidding? When are you going to be able to spend two or three years where there's nothing to do but try to figure out how you can make work that may not work. It can fail, it can be experimental, it can be ugly, and everyone is going to be really willing to look at it and think about it. It's not about success but productive failure, where you can try things that are compete disasters.” I think that's what grad school is amazing for.

How important is it for artists today to learn the technical disciplines of life drawing and other traditional modes of academic training?

That depends on the world that you're going to be in, because the art world is big and art training is pretty vast. There are whole worlds of people who need to learn how to draw, and then there are whole worlds of people who never need to pick up a pencil—it depends on what field you want to get into, and both approaches are totally reasonable. I used to have this joke with a friend when we realized that there are these watercolor magazines profiling all these people in the art world who are completely unknown to us. We were like, “I don’t know about Lester Gravenstein—do you?" “No, but he's very famous in watercolor.” We imagined that maybe there was an equivalent for everyone we know in the watercolor world, where you have to know things that we don’t know how to do, like make flesh tones of watercolors. You know, Artforum has a Bookforum that comes out once a month, but they don’t have Watercolorforum. Maybe they should.

I'm sure it would be very popular. Another medium that has grabbed your attention in recent years has been digital animation, which you've begun creating on your iPhone and iPad. You mentioned that when you're working on paintings you like to be able to have shapes flicker in and out of the composition, so I wonder how these animations relate to your paintings?

It was really helpful for me to get an iPhone, because basically it let me start drawing and saving and drawing and saving and drawing and saving in a way that I didn’t do before. When I'm making a physical painting, in order to make the next layer of a composition, I have to change what's there and wreck it and overrule it, so it's much more pleasant and kind of liberating to suddenly have the past available. It’s like having time in my toolbox, which is what people who take photographs have always had, because photographs by nature have the time of the instant that the shutter clicks. With painting or drawing you don’t have the moment as much as you have a kind of long, expanded time. I wrote an essay about this once were I said that painting was like a compression of time, whereas film or animation or anything photographic was a slice of time like an endless set of slices, so you have lots of little bits—and having lots of little bits is what physical culture is.

What direction do you find your paintings going in today?

I don’t really have a direction, but I have some different interests. I'm interested in still lifes, and many of the paintings I'm doing now are kind of still-life-ish. There's also a grid kind of thing that I've been getting into. Then there's the ongoing animations, which have to do with making paintings really fast using the procedures of digital drawing, and that really speeds things up, because the still lifes and grid paintings are really slow. So I have like three different things that are going on all at once, which is why at this point I feel like I have too much to do.

Are there any novel approaches to painting that other artists are taking that you find attractive?

No, there's nothing novel. I don’t mean that in a bad way—I just don’t think that's what painting is about. I don’t know what would be quote-unquote “new.” Painting isn’t about the new, you know, and it's not about novelty, because everything in painting has a very narrow gauge. It's a very intense medium. Somebody said to me once, “Sculpture is everywhere!” You can go down the street and see like orange cones on a black car and say, “It’s like sculpture!” But painting has a narrow gauge—it's very specific. It has a surface and a certain kind of preparation. It's like, you wouldn’t ask, “What are they doing in novels?” Sure, there can be experiments with punctuation and grammar and doing things like having no vowels, but even these experiments are not chronologically new.

So, to parallel a question that sportscasters might ask athletes who make it into the Super Bowl, how does it feel to be in the Biennial this year?

It's been really great. I felt really relaxed. Michelle has been really generous and an awesome curator in the sense that she is an artist but doesn’t act like one, in that she is very open to the ideas of the other artists. She’s very trusting and supporting in a hands-off way—that was my experience with her as a curator. Michelle has chosen really interesting people for the show, and it seems to me it's going to be a very crowded and really jolly Biennial. That was the vibe when I was there the other day—I felt jolly.

As someone who has worked with so many young aspiring artists, what do you make of the Whitney Biennial as an institution?

Well, it seems they keep inviting really interesting people to curate it. People always says, “Oh, it's the show that everyone loves to hate.” I'm always really interested in what they have in there. The Biennial is fascinating because it's a show that's in a museum, and when you go to a museum you always remember something from the last time you were there. When I walk into the building, I still remember going to Biennials and group shows from when I was first an art student living in New York when I was 20—the building is such a profound space. So while the art is always new, if you’ve reached a certain age in New York you have been to the building a hundred times, and I've been to 30 Biennials or something. And you can always remember what you saw there, and there's something great about that because it's like a fraction where the lower half of the number remains the same. I don’t know what it's going to be like when they go to a new building.

And then the Met is going to take over the Breuer building.

And then you're going to have even weirder old memories—you'll walk into a room that you or people you know showed in, and what are they going to have in there? Hoppers? Wouldn’t it be great if they put a Sienese painting next to one of the Beuer windows? God, I hope they put the Italian Renaissance stuff in there.

Then they could have the Metropolitan Museum of Art Renaissance Biennial.

That would be funny: “The best new dead art.”

The Ancient Egyptian Sculpture Biennial.

The best of the tombs! What's new in the tombs? You could have a really good interview with somebody from Ancient Egypt. "What directions are you interested in now? What’s new in your world?" That's something I would love to read.

READ THE REST OF OUR WHITNEY BIENNIAL COVERAGE

Curator Michelle Grabner On Her Unruly "Curriculum"

Curator Stuart Comer On His Shapeshifting Presentation

Curator Anthony Elms On The Rise Of Literary Art And The Usefulness Of Ghosts

5 Ways Of Looking At The 2014 Whitney Biennial

A Brief History Of The Whitney Biennial, America's Most Controversial Art Show