Andrea Crespo’s art seems to check all the boxes indicating a young artist who grew up on the internet, savvy to the sleek aesthetics of—for lack of a better term—post-internet art. Drawings reminiscent of fan art found on the user-generated digital galleries of DeviantArt are made using a digital tablet and image-rendering software before being digitally printed on satin, for instance. But while these indicators might be true (Crespo is, in fact, very young—24 to be precise—and did in fact spend many formative years immersed in online media) there is something about the artist’s work that is truly unique. As a self-identified “transgender dicephalophilic person with a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome,” Crespo’s work offers a raw and intimate glimpse into a mind that doesn’t quite identify with the physical form it embodies. To clarify, “dicephalophilic” here means an affinity for dicephalic parapagus twins—a difficult-to-pronounce term for conjoined twins who share a single torso and set of legs but have two separate, side-by-side heads.

In the press release for Crespo’s recent solo show at Downs & Ross, the artist writes “I, for one, have found my identity and body-image to be inextricable from televised footage of the dicephalic conjoined twins Abby and Brittany Hensel.” You may know which twins the artist is talking about—they’ve had a reality show called Abby & Brittany , have been featured in documentaries on TLC and the BBC, and have had countless articles written about their fascinating, and quite frankly, statistically near-impossible lives. Born in 1990, Abby and Brittany, who each have one head and spinal column and control one arm and one leg of their shared body, have triggered a transformation in Crespo, who first saw the Hensels on television at the tender age of six.

Crespo writes in the same press release, "When people ask me if I use 'they' pronouns in the neutral or plural sense, I’m left without appropriate words.” While the pronoun “they” has been an increasingly popular for those who don’t identify as a binary gender (he or she), the fact that it’s plural is typically an unfortunate afterthought. For Crespo though, it seems like a serendipitous fit. “Many of us are somewhat familiar with the notion of people contending with the grating compulsion to alter a gender through artificial (not to be read as inauthentic) means, but few of us have heard of one wanting to be two, two women to be exact, or at least one of two enfleshed in the same body," writes Crespo. "Don’t ask me why and how, for it is just as confounding to medical experts as how Abby and Brittany can play volleyball or drive an automobile.”

Crespo’s solo show “Joined Together” at Downs & Ross (formerly Tomorrow Gallery and Hester, respectively) that spanned two locations in the Lower East side closed last week. The most literal and explanatory work in the show was parapagus , an hour-and-45-minute film that, narrated by the artist, offered a voyeuristic glimpse into Crespo’s formerly very private inner world . Here, Artspace’s editor-in-chief Loney Abrams speaks with Crespo over coffee in a Chinatown park about the film, their transformation, conjoined twins, and Christianity.

In your newest video parapagus , a character (presumably you) has a session with a psychiatrist, and the conversation that you have with him provides a loose structure for an unfolding narrative. As a viewer, I watch your video and I find myself feeling a bit uncomfortable in my relationship to these characters. You speak so honestly and openly about experiences that have caused you a lot of pain and embarrassment; you really become vulnerable—and as an empathetic person I respond emotionally to that. But ultimately, the character I relate to most is the psychiatrist, I think. I share his curiosity and concern. Who do you imagine your audience being and which characters do you imagine your audience identifying with?

Everyone. People who are in a similar position to me as well as those who have never even thought of this as a possibility.

I guess what I mean by saying it makes me uncomfortable is that it makes me feel like I’m “othering” you, in a way. And while I’m doing that, and re-affirming my own relative “normalcy,” I feel embarrassed or guilty about it while I’m also, like the psychiatrist, curious to uncover something private. I feel like a voyeur. What do you make of that? Is it important that the viewer get into a somewhat unsettled state while watching this video so that we’re somehow primed to receive it?

I think it is important that viewers are aware of this. There are ways in which the film parallels “edutainment” genres and forms that purport to educate viewers constructed as “normal” about the lives of those conceived of as a little different or abnormal. I’m turning myself into an object of knowledge for others, but in a way that doesn’t relinquish too much agency to the viewers or “knowers.” I guess this dynamic is so naturalized that I feel I’ve accomplished something in just drawing attention to it; this opens up possibilities for reconfigured relationships.

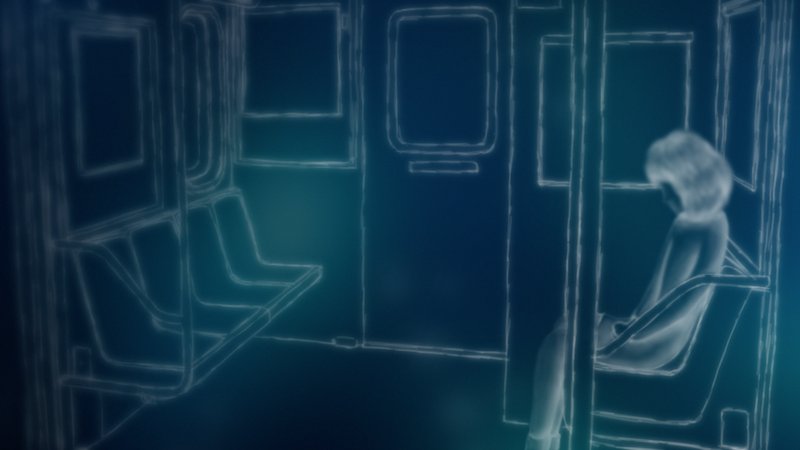

Still from

parapagus

(2017)

Still from

parapagus

(2017)

There are obviously many different responses to this video; mine is just one. Have you heard from any viewers that really related to your experience? Anyone who you didn’t previously know but ended up meeting because of this shared experience?

I've been contacted by people with related experiences, but not exactly the same experience. There are still commonalities with a lot of people's experiences even if it's not the same exact form.

Does that surprise you?

It's not surprising because I feel like a lot of people have inexplicable experiences of a similar sort and perhaps don't share them because they haven't been made intelligible. Even if it's relatively rare, it's probably a sizable portion of the population.

Was that part of the impetus for making this work?

I think it was, partially so. I didn’t make the work just to reach that audience, but it was something I kept in mind. I was very mindful of people who can relate in this way.

Is spreading awareness important to you?

Yeah. I think that I also just want people to start their own conversations in response to the work, maybe with different ends. I think I'm offering my story and my subjectivity—a narrative—to people so that they can not only learn something from me but also be stimulated and relate it to their own experience of being in a body and of bodily difference, whatever that may be, or whatever form that may take.

Installation view of "Joined for Life" at Downs & Ross

Installation view of "Joined for Life" at Downs & Ross

Your videos feel very clinical, in a way. In older videos you show diagrams that look like they might come from medical textbooks, and in parapagus you meet with a psychiatrist and much of the video is set in a hospital. Contextualizing your story within the realm of science doesn’t seem like an obvious choice to me. Transgender issues have become mainstream issues; and trans-“anything” has become a buzzword. I imagine that as an artist you might feel an impulse to ride that wave and utilize the energy that surrounds these political issues to foreground your experience in the realm of identity politics. But your work doesn’t feel, to me at least, overtly political or activist but instead feels much more open-ended and exploratory. Is there a reason you root your narrative in science?

I think the work is already political. It's just not expressed in positions that align with mainstream transgender or queer discourse, and maybe that's why it’s not read as political. But I think it presents an alternative position that may come from a similar place, but I guess I've reached very different conclusions about my being and becoming in the world. I think I have different ideas about that.

And how about your decision to treat this narrative in a clinical way? You chose to depict a conversation between you and a psychiatrist at a hospital, rather than a friend in your apartment, or even your diary or journal. What prompted you to locate this conversation within a scientific/medical environment?

I think one of the ways to access this narrative is through clinical discourses, which are overarching, dominant modes in describing the embodied phenomena I’ve experienced. But I think the work also expresses more mystical forms of conceiving of such . There are Christian themes in the work—not to say that they’re opposed to the medical and scientific threads. I think there are many discourses informing each other; both medical and religious. I think those historical tensions are expressed in my work as well as my daily experiences.

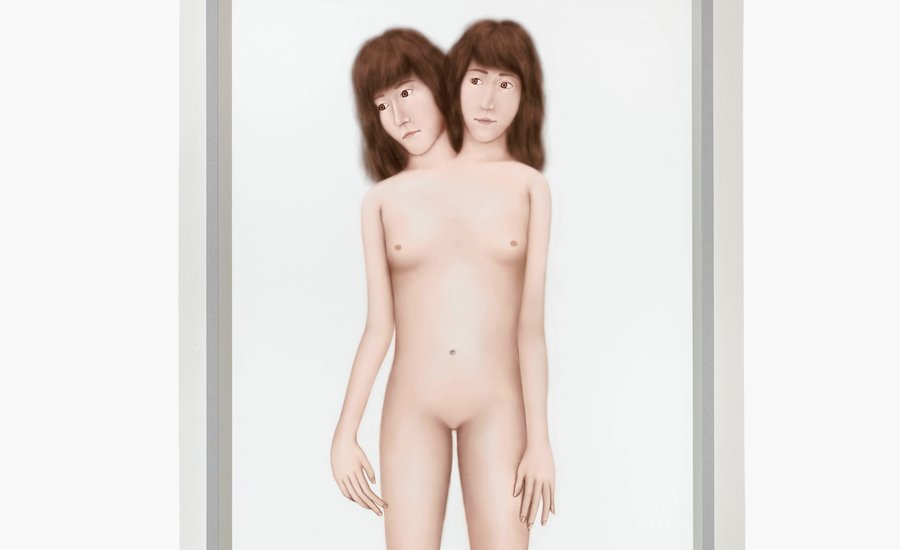

Annunciation, Cynthia and Celinde (2010)

, 2017

Annunciation, Cynthia and Celinde (2010)

, 2017

Can you talk a little bit more about the Christian themes?

These clinical terms fall short of describing my experiences, ultimately. They point towards something that's real but they're fictions that can only approximate describing my experiences. In Christianity (particularly Catholicism) there are ways of thinking about corporeality that have been useful to me in thinking about my own body. There are Christian references to the convulsive body, which has this medical history but also a history tied to possession and demonic phenomena. And this bodily struggle is constructed as the self versus some kind of unwieldy bodily materiality, it’s all about corporeal integrity/unity or the lack of it. And though convulsive shaking can be seen as demonic, it can also be seen as ecstatic—a result of religious ecstasy. Like, for example, the feeling of being pierced through and permanently transformed by an ecstatic experience. So, those kinds of Christian forms of understanding bodily phenomenon proved to be very helpful to me.

I imagine that even the idea that there is an afterlife—which implies that you have a soul or being that is separate from your body, and that soul or being can leave and become embodied elsewhere—can be helpful in understanding a disconnect between body and being. The idea that there’s something beyond the body, that consciousness can be, in a way, separate or disconnected from a body, is something that science can never really come to terms with. Did you come to find Christianity as part of your transformation or were you raised Christian from the outset?

I was raised Christian but I totally moved away from it because, between my gender issues and my disability issues, I just didn't see it fitting. I also felt very rejected by the Church. I feel that in my work I continually find myself resonating with my Christian upbringing and how I understand myself. Now I am embracing that more but on completely different terms that are perhaps a bit more forgiving towards my differences.

So you really found solace in the spiritual and philosophical aspects of religion. For so many people, religion is all about the community, but in your case, participating in that community wasn’t healthy or supportive. In parapagus you talk a lot about how alone you were in your experience, about feeling embarrassed and ashamed. You were so private; you even tore up your drawings so that your mother didn’t see them. How did you go from that to sharing your story so openly and honestly? And why did you choose to share your story in the form of art?

It has been a very long process of transformation. And it’s involved a change of expectations in terms of how these things might be received by others. Also, the world has changed since a lot of these experiences started for me. I feel like now is a time when people are starting to really think about a lot of the issues that are presented in the work: a certain focus on identity, a certain focus on the bounded-ness of the subject. I feel like people are thinking about a lot of questions that my experiences are related to. So that was a part of it too—it wasn't just me getting to a point where I was more ready. The world became more ready, too.

In this video you talk about different coping mechanisms that you use. Is this body of work a coping mechanism?

I think so. It's a way of doing that that also keeps an audience in mind. It addresses concerns beyond coping, but that is a part of it.

What has the reaction to this work been like?

I’ve had a whole range of responses from people. Some of the responses that stick with me are from people who describe being emotionally overwhelmed or even physiologically overwhelmed. Someone said that they even felt like they were shaking, and other people were moved to tears. That to me shows that the work is registering with people on a level beyond cognition, or beyond a scholarly interest or formal interest.

DeviantArt has had a big influence on you. That’s where you first discovered drawings of conjoined twins and you found some comfort in knowing that other people shared a similar fascination. Have you shared any of your work on DeviantArt?

In the past, yes. But this work I haven’t shared to the whole community on DeviantArt—just perhaps my friends.

Can you talk about how these images that you were finding on DeviantArt influenced not only your work but also your understanding of your self-image and yourself?

I think that in some ways they were a step along the way. There's a way in which my practice started with that, and then moved away from it with some of the same themes or experiences being addressed. I feel like this Deviantart stuff is the tip of the iceberg. I think it’s just one of the ways in which these broader experiences have crystallized and made themselves visible.

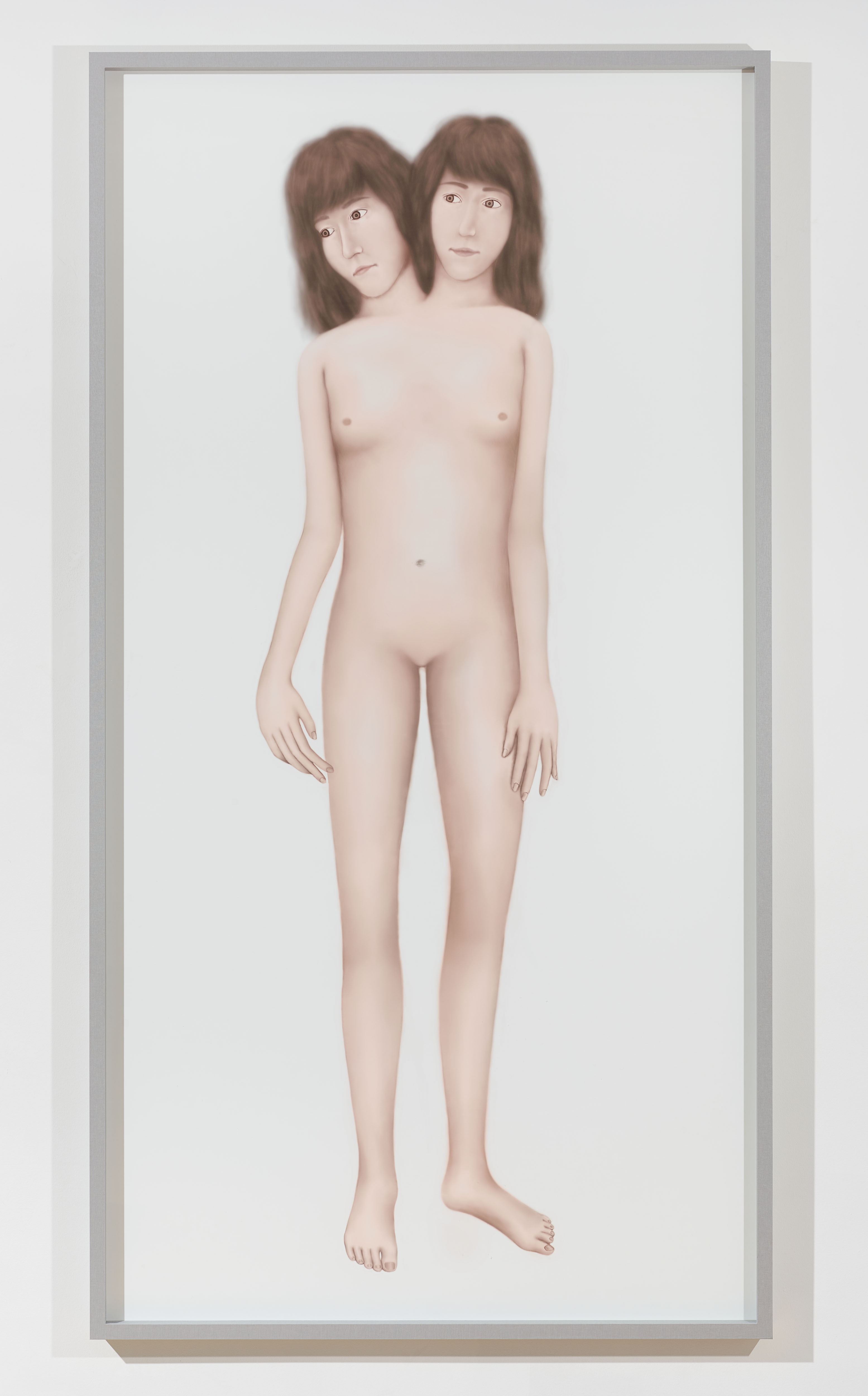

Together Forever

, 2017

Together Forever

, 2017

Another influential media was a TLC documentary about Abby and Brittany Hensel, conjoined twin girls slightly older than you. Can you talk about your relationship to them and how they fit into your work?

Well, I think that a lot of this started when I first saw them—in the ‘90s, when I was six.

Conjoined twins are the subjects of your work, but sometimes the figures you create are very clearly the Hensel twins, sometimes they seem like fictional characters, and sometimes they feel like your self-portraits.

The Hensels were very crucial in the formation of my body image and how I see myself, even if there's a discrepancy between how my body is and how I see myself. The portraits of them are about their influence, and about the way my body has received those images of them and reprocessed them. And I think my self-portraiture really focuses on myself as I imagine myself to be.

Your portraits of the Hensels are very clearly renderings of images taken from the media. For example, in one of your drawings you’ve included the LIFE Magazine logo on the top corner. Some of your other drawings, which I assume depict you as a child, are of you watching television. So it’s clear you think about your relationship to the Hensel twins as mediated by the television or by print media. And the media portrays them in a very particular way. They’re real people but they’re also dramatized. They’re celebrated for leading “normal” lives, and we cheer for them as they excel at softball, as they apply for their driver’s licenses, as they flirt with the boys at school. Meanwhile, you say that “I’ve spent most of my life wishing to be normal, if not downright despising my psychiatric and neurological divergence. Perhaps a lifetime yearning for normalcy is not without its inverse: desiring a specific and outwardly visible physiological abnormality. I can’t help but compare my shortcomings with Abby and Brittany’s cognitive and behavioral typicality.”

So, I’m wondering if your response to these twins is somehow wrapped up in that way the media portrayed them and focused on their successes. And whether your work might be about your own personal experience, but also may be about how media, in general, can have a huge impact on how we see ourselves.

Yeah, I've thought about that a lot and I've had that question directed at me many times before. People ask me, “Do you think that the way that they were mediated and the way that their narrative was constructed and sensationalized shaped how I was affected?” It's hard to know. Who’s to say that the same thing wouldn't have happened if I saw them in person, in real life, when I was six years old? There's no way to know. Perhaps interacting with someone prevents a lot of the kind of mis-recognitions that can happen through this unilateral medium like television, where there's no reciprocation—there's just you looking at the image and piecing together a narrative from media that is strictly audio-visual.

Part of Your World III (2006)

, 2017

Part of Your World III (2006)

, 2017

Everyone does this, right? Kids watch television shows, and the ways in which genders are depicted on those shows, for example, can shape the ways in which those children perform their own genders. Or some adults see so many advertisements with models that they begin to see themselves as overweight when they aren’t. I mean, those examples are overly simplified, but it’s not so surprising to think that your own self-image is based on media that you consume.

Right, I think that's the intention of a lot of media. But I question to what extent these mediated narratives affected me, because what I do feel confident in saying is: the outcome in my experience is not the intended outcome of this media.

Right.

For most people, seeing the Hensel twins probably verified their own body image and normalcy, whereas for me it intensified feelings of identification with them—a kind of identification that changes me, not upholds who I think I am and the comfort and integrity of myself; it actually acts to reconfigure that. It's transformative. And that goes back to the Christian themes we were talking about like ecstasy. The image of the piercing arrow is invoked. For me, the imagery of those twins cut through me; it changed my life. I don't think that is what this kind of media is trying to achieve. Most people don't respond how I did.

You responded to seeing these conjoined twins in a lot of different ways, but one of the ways was physical. It made you feel a physical absence, as if you were missing a part of you. I think everyone can relate to the desire to be close to someone else. We use the term “inseparable” to describe friends or lovers who aren’t actually conjoined but are intimately connected. But I think for most people, this desire to be with involves searching outside of oneself for someone else. This might be a stupid question, but I’m wondering, in your case, is it that you already have that other person, you just desire the physical manifestation of that person? In other words, do you have two minds, and the issue is that you only have one body?

It's almost like a potential for that rather than literally two people, but there's this kind of reaching towards that that mentally happens. I don't know if I want to call that simulated or potential or virtual, because there's clearly some somatic manifestations—sometimes I have feelings on one side of my body that feel actual, and then at other times I see it as a kind of effect of my situation, as a perceptual thing. But that’s actually exactly what this is about—a perceptual or proprioceptive body-mapping difference, or error, or whatever we call it. It’s a very murky thing and it’s difficult to pin down. There isn’t much in terms of language to describe what this even feels like without dismissing it, calling it illusory, or saying that I am actually two people, none of which are true. But there is something true to what's going on even if we don't understand what it is.

You express your plural perspective in your work, not only by the imagery you use, but also by having stereo sound on your video where your voice is at some points overlapping itself, and at other points it splits and becomes two people. I’m wondering how this perspective translates to your physical works. At your Downs & Ross show you have some drawings printed on satin with custom aluminum frames. Do those forms reference something in particular?

Yeah, they're somewhat very reduced bodily silhouettes, but combined with the spinal braces that are depicted in the documentaries featuring the Hensel twins. So, the idea of bracing or fixing the body at developmentally crucial points is evoked through these. They also have a kind of cellular quality, mitotic almost, referencing the partial splitting of a fertilized egg.

And your prints on satin, a soft fabric, reminded me of that feeling you get at when you mention a cheek against a cheek.

That tactile quality is important.

This show at Downs & Ross, and parapagus in particular, felt like the most explanatory and the most personal of your works thus far. You really laid yourself bare. How do you move on from that in terms of your work? What comes next?

I have many ideas! I think there's a lot of directions I can take and I'm not really ready to speak on that.