For her current, immersive multi-channel video installation at The Kitchen , up-and-coming artist Meriem Benanni explores the generational conflict between two Moroccan chikha singers, combining the artist's own footage with fantastic and absurd digital manipulations and animations. The playful and hypnotic installation is a compassionate and comic skip through the small Moroccan village of Safi, brimming with the cartoonish humor that was characteristic of Benanni's critically lauded exhibitions at MoMa PS1, Art Dubai, and the Barclay's Center Oculus.

Historically a form of anti-colonial resistance during French occupation, aita— an incredibly visceral song and dance that makes twerking look like a Victorian waltz—was a form of activism translated through the voices and bodies of women. In Benanni's Siham and Hafida , the eponymous protagonist chikhas (dancers who perform in the aita tradition) take us through their own versions of aita amidst Bennani's digital flurry of scuttling animated crabs and meandering flocks of butterflies. Hafida, the elder, veteran performer rooted in tradition butts heads with Siham, the millennial whose constant selfies and phone addiction are symptomatic of her revolutionary desire to update aita in the 21st century.

While nearly all of her major exhibited work over the past several years is rooted in her home country of Morocco, Meriem Bennani is reluctant to identify herself as a Moroccan-Muslim woman artist. In the following conversation with Artspace's Shannon Lee, Bennani discusses that hesitation and the traps that come with identity conformity, as well as her show at The Kitchen, chikha culture, and Youtube's role in becoming an archive of an undocumented Morrocan-Arabic dialect. Her show Siham and Hafida is on view at The Kitchen until October 21st.

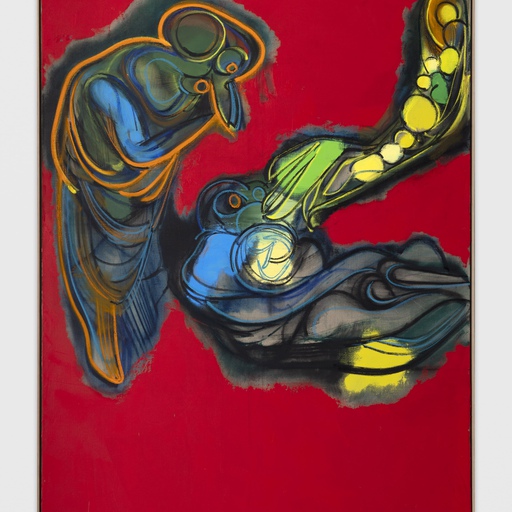

Installation view of "Siham and Hafida" at The Kitchen

Installation view of "Siham and Hafida" at The Kitchen

How did this show at The Kitchen come about? Did you already have a concept in mind when they approached you?

It’s very straightforward. I had met with [The Kitchen’s curator] Lumi [Tan] once before and then she wrote me a couple months ago asking if I would be interested in having a show in September. I was excited to work with her because I really like her program and The Kitchen is an incredible space both in its history and what they do today. It was also ideal for the type of work I do—they are a gallery but they also have a theater, it’s not a white-cube space, and there are no windows. It’s a playground for me, so it was really exciting to have the opportunity. I knew I’d do another video-based installation because of the nature of the space, and I knew I wanted it to have to do with music, sound, and performance art because of The Kitchen’s history.

I had been really interested in this Moroccan song and dance form called chikha, and particularly this one chikha dancer named Iman Tsunami who has become really famous in the last couple of years in Morocco. I’d been following her, watching everything she’s done on Youtube, and finally asked if I could do this show about her realizing it’d be a perfect show for The Kitchen.

I had planned to go to Morocco to film her in July and edit in August, but when I got there she completely flaked! She could only give me about two hours of her time and I realized that even though I was obsessed with filming her, I needed people who would give me more of their time. Luckily, I had a plan B, which was to go to the city of Safi, the capital of Aita music (the music of the chikha). In doing research, one man's name kept coming up. I contacted him on Facebook and he was really excited that someone younger than him was interested in the art and he told me about this older woman, Hafida, who had performed with some of the most famous chikhas. Then, he told me about the younger Siham who I was really excited about filming because she seemed to have a really contemporary take on the art. He arranged for me to spend two days at each of their houses.

That’s how the narrative structure of the film came about—very naturally. He had told me that the two weren’t really friends but he really wanted them to meet. I really wanted to investigate the idea that the younger performer wasn’t accepted by her elder and was isolated by the others in the community. When I got to Hafida’s house and she found out I was also meeting with Siham, she got pretty uptight and explained that Siham was isolating herself. The drama between them took over—I barely had to push it. To be honest, I didn’t know what I was looking for and the video itself is that exploration.

Video still picturing Siham (left) and Hafida (right).

Video still picturing Siham (left) and Hafida (right).

I love the cultural rift that happens between this older, more traditional generation and this newer, contemporary one in a dance form that’s so historically rooted in female empowerment. Do you think that schism reflects an evolving feminism in Morocco?

The generational conflict aspect of this video is very universal. The video is about a very specific art form and two very specific people and through them, I’m talking about an issue that can be applied to any generational gap. The elements that are threatening to Hafida as an older woman are universal—you see them in any dance, music, art, office environment… anywhere. I’m always very interested in making not purely Moroccan work because I don’t even really know what that means. I do film mostly in Morocco because something about it viscerally attracts and excites me, but it’s just a starting point and what I’m interested in is making something that can be read on many levels.

In terms of feminism, it’s an interesting thing because the musical genre has ties to activism, and the activism is circulated through women’s bodies, so it is very feminist. But I have to say, sadly one way that it is feminist is that it bothers people. These women get a lot of shit. It’s feminist actively, but it’s also passively feminist just because it goes against the patriarchy. It’s independent women working through their bodies. In the case of Siham and Hafida, they make as much money as their husbands. The chikha is a money-making machine and they treat it like a job.

Do you feel like chikhas still identify with the revolutionary and political aspects of Aita music?

I wonder, because a lot of Aita lyrics were very activist during French colonization. But this is a musical genre that isn’t activated through generations because the songs are all part of a repertoire—there are no new chikha songs. They were all written a lot time ago so in a way, it’s like… how revolutionary can you be when you don’t reflect your own time? What’s really revolutionary in what Siham is doing lies in the fact that she’s literate and Hafida is not—the whole generation before Siham is illiterate. And because Siham can read and write and is fluent in social media, she wants to make videos with subtitled lyrics to the songs she sings, which is incredible because there are very few transcriptions of these songs available. None of it had been written down. Her desire to use the internet as an archive is one of the most revolutionary things you could do, and I think Youtube is playing a very crucial role. Aita is a musical genre with lyrics that are in an old, oral dialect but Youtube has organically become this songbook and archive of the tradition. It’s an old Moroccan-Arabic dialect that, apart from Aita music, is otherwise lost. Youtube is like a history book, saving and circulating this language.

Installation view of "Siham and Hafida" at The Kitchen

Installation view of "Siham and Hafida" at The Kitchen

I noticed that your earlier work is a lot broader in its subject matter. When did Morocco become a central focus for your work?

I was mostly doing drawing and animation in the beginning. Then I started filming stuff with my iPhone and at the time, I was going to Morocco a lot—a place where I felt really excited and stimulated. I would film my family and the streets, and the work developed from that over the past year or two. I’m always wary of being pigeon-holed and am already thinking about what I want to film next that isn't just Morocco and my family. I’m really hyperactive and interested in so many things and I get bored pretty quickly, which is a problem sometimes because I’ll explore something for a second and won’t stay with it long enough. I wouldn’t say I want to make films about Morocco forever. I just think that home is such a sensitive and awkward thing that it brings out a lot of tension and narrative.

Speaking to that issue of identity, in your Art21 video you talk about not wanting to be identified as a Moroccan-Muslim woman artist, and it reminded of Kara Walker's statement about her current show at Sikkema Jenkins . She states, "I am tired, tired of standing up, being counted, tired of ‘having a voice,’ or worse, ‘being a role model.’ Tired, true, of being a featured member of my racial group and/or my gender niche." That seems like a really important, salient sentiment to express as a minority woman artist.

Yeah, it’s exhausting. I’m sure she feels dead! I’ve only been filming Morocco for a year or two and I already feel it. Whenever there’s an article about someone that isn’t from America, one out of two times, cultural identity becomes the subject, which I find very exhausting. If I talk too much about it, we’re doing the pigeon-holing thing. I imagine someone from New York, for example, has 100 percent of the space that is given to them to talk about a new piece. When you’re a woman, then 20 percent of the conversation is about being a woman and if you’re a woman from another country, then 40 percent of the conversation is about that. In some ways, my work has less visibility because half of my press has to do with how people want to categorize me. There’s a messed-up logic to it that I find exhausting. It’s really limiting! Because in the conversations where people want to talk about your identity, you aren’t really talking. They’re just asking you to confirm tropes. Not saying you’re doing that, but it happens a lot.

You're fairly well recognized on social media, particularly on Instagram. What role do these platforms play in your work?

To be completely honest, social media is not that important to me. I barely post on Instagram but it is a really interesting platform that’s allowed me to develop a new language that’s quick and spontaneous. It provides instant feedback and a way for me to meet people and give my work visibility, but I really don’t care about it as a medium. I find its potential very limited in my work. I think my work will only get better the further away I get from the fifteen-second to one-minute video format by going more in-depth into real narratives instead of vignettes. I don’t have a problem with Instagram and I think it’s fun, but it’s mostly fun in a social way. I know a lot of people who do amazing work with Instagram but that’s not me.

You’ve said that you see humor as survival. In our current crisis climate, comedians and satirists have become critical voices. What's so refreshing about the sense of humor in your work is that it doesn’t come off as an indictment or satire—it's much more celebratory. Is that deliberate?

The humor for me is very spontaneous. I don’t think I have very elaborate humor. The jokes are very straightforward and childish, very old-school cartoony.

Tennis Funjab

Tennis Funjab

It reminds me a lot of magical realism.

I think that’s a right term to describe it. It’s a surrealist humor, placing it in a world that has different rules so it doesn’t have the same weight. You can push it further and it’s still okay. But is it deliberate? I don’t know; I think I’m just a positive person. I love dark humor but it’s not what I do.

What makes you laugh?

Oh my god. The most basic stuff makes me laugh. I love Saturday Night Live , American comedy, cartoons, my friends… I appreciate any comedy when it’s smart.

RELATED ARTICLES: