When

Mika Tajima

moved into her current studio on an industrial stretch of Grattan Street in Bushwick eight years ago, most of the building was still occupied by a sweatshop that produced children's clothing. Now, hers is just the latest block in Brooklyn to see the blossoming of an organic health food store, a wine shop, and other bohemian amenities where there was once industrial sprawl.

Tajima's long tenure in the neighborhood separates her from the proliferation of younger artists who have flocked to the art chasing cheap rents and a bohemian vibe—after all, she was initially drawn by the the post-industrial setting, which happens to suit her work. Tajima has a special interest in the mechanics of production, and the mental and physical transformations that industrial design places on the human body. All of Tajima's work entail meta-productions about the act of production. Her installations bridge sculpture and performance, implicating the body—whether those of her collaborators, of the audience, or, as was the case in her recent gallery show at

Eleven Rivington

, of professional contortionists—as an element to be shaped and guided by the artist's environments, which are often built from pieces of high-end Modernist design.

Aside from reminiscing about the neighborhood, Tajima allowed

Artspace

into her studio to tell us about her work's overlapping of performance and production, her collaborative work as part of

New Humans

, and her horizontal move from the office cubicle to the hot tub for her upcoming show at

Art in General

.

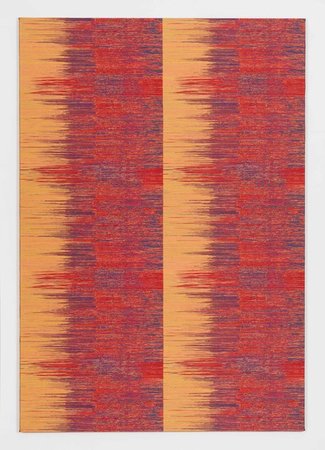

Negative Entropy (Langhorne Carpet Mill, quad),

2014, made in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, courtesy of Eleven Rivington

Negative Entropy (Langhorne Carpet Mill, quad),

2014, made in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, courtesy of Eleven Rivington

I’m interested in your newest works, the "Negative Entropy" series, and their relationship with technology. Could you explain the process of making them? I think in your work there’s generally an interesting back-and-forth between modes of art and mass production.

The two series of work shown at Eleven Rivington are both mediated by some kind of industrial process with different material qualities: plastic and fabric. I wanted to look at the transformation of industrial economies to information-based economies, focusing on the global flow of life energies and materialities between unraveling systems.

The “Negative Entropy” series—the woven acoustic portraits—came from an artist residency at the Fabric Workshop in Philadelphia. As a city, Philadelphia is a specific example of one of these transforming economies, since it was once a textile center in the U.S. but has been in gradual decline for over 50 years. There are still a few remaining factories, but most of the industry has shipped off to places abroad while being replaced by an ascendant information-technology economy, such as server colocation centers and communications companies, that kind of thing.

So I went to both types of places and recorded the sound of the respective machines working. With the old textile factories, there’s always a human worker present, so there’s worker intervention still happening—versus the information tech places that we went to, where there was virtually no one around, just white noise and the soft hum of machines. I captured audio at both places, and then worked with a sound technician to transmute the recordings into spectrograms, or visual images of the sound.

I worked with the staff at the Fabric Workshop to assign color to the various sound patterns, and then I gave those images to the weaving designer at the particular mill where we recorded the original sounds, and they were woven into textiles. In a sense the works display the sound of their own making and inscribe their own death. A portrait is a frozen image of a particular time. These portraits are a mute image of a passing moment.

The process is also about taking the production of the work and distributing it to various people, who “perform” different roles in production, which is something that I think is very interesting in the performance-based projects that you’ve done—the idea of performative roles. But in contrast to your earlier work, here the product is an object as opposed to an environment or an event.

I am interested in the relationship between performance and work. How does one perform work? What are the expectations and conditions? What do we make? Sometimes it's material and sometimes it produces something else that is ephemeral or even abstract. The acoustic portraits capture both of these registers.

How are the colors determined?

The color selection is based on palettes that reference Modernist interior design color systems that pushed the limit of industrializing aesthetics and its applications. My color selections are intensified or unlikely versions of these systems. Think Herman Miller, or Artek on acid.

I want to come back to the earlier projects in a moment, but one thing that the "Negative Entropy" series reminds me of is Bauhaus textiles, and that made me wonder how much you’re thinking about art history or past work. Formally, in a lot of your work, I see a kind of Constructivist aesthetic, but also a lot of Minimalist influence, structurally. How much do those kind of references come into play for you?

I think a lot about how we live with the legacy of those practices—I'm interested in the inversion and contradictions inherent in these past artistic projects. For instance, how did certain strains of Modernist rationalism ultimately work against human freedom and desires? Some of my works use historical source material to examine our contemporary way of seeing the diagrammatic, particularly in interior corporate architecture—the naturalized spaces of work and life.

The folding screen pieces, for instance, which might look Constructivist or allude to a Sol LeWitt -type wall drawing, are actually coming from office cubicle diagrams that schematize the way people should work. These things are very much in my mind, but rather than see them as the idealized version of historical models, for me it’s more about how we see them, now—how they’re integrated into our lives.

No Go

, 2010, courtesy of Formalist Sidewalk Poetry Club

No Go

, 2010, courtesy of Formalist Sidewalk Poetry Club

It’s like the flip side of the Modernist marrying of everyday life and art—making art serve compartmentalized production, rather than some utopian ideal. The cubicle designs you use are actually original Herman Miller pieces, too, but reconfigured. How did you come across those designs, and where did you find the pieces?

Some of the earlier double-sided panel works I did referenced the first cubicle system invented, called the Action Office System by Herman Miller. They were made in the late 1960s and went into production in ’69 or ’70. Its original design intent was to maximize all the qualities now valorized in actors within the information economy: creativity, freedom, flexibility, collaboration, networking, transparency, self-management, et cetera. The idea was for the workers to perform in this workspace.

Part of the challenge of the Action Office System was to reconcile the industrial imperative with the human element within its aesthetic design—their effort to humanize these spaces using artistic décor. When I was first researching the panel system it struck me how the surfaces were like paintings. I’d been working with a carpenter to build these double-sided panels, but after doing a few fabricated versions I wanted to use the actual system as a readymade. I went on Craigslist searching for the first run of these panels, and I eventually found a whole set of them that were being sold by a telemarketing center in Bayone, New Jersey, that was liquidating everything in their office. So I drove in a truck and loaded up all the panels they had. They were like, “Oh my god, who wants these? Great, here, take them! Get them out of our sight!”

Why was it important to have the authentic Herman Miller units?

After the financial crisis in 2008, I was really thinking hard about my own way of making objects. If I was going to do a gallery show, it made sense for me to acknowledge the setting of the commercial gallery space as a kind of evacuated showroom. I kept some of the original fabric and re-stretched some of the panels with canvas and painted them monochrome and then configured them into various improbable or unusable types of shapes, like cubes, or flat wall configurations. These objects, alongside my "Furniture Art" series of paintings, underlined the surfaces and interior/exterior spaces created by these structures—paint trapped in transparent shells and cubicles with no entry or exit.

Coming back to your performative works through the lens of interior-versus-exterior is interesting—as a viewer, going into your constructed environments, it’s not really clear what’s the inside of the work and what’s the outside—who the performers are and who the audience is. Part of that is the fact that you bring in creative people from other fields—philosophers, historians—as performers.

The project you’re referring to was “Today Is Not a Dress Rehearsal” at SFMoMA, and that was a collaboration with New Humans (my collaborative group) and Charles Atlas , who’s a seminal filmmaker and video artist. We wanted to do a film production as performance, using the moveable sculptural set as a skeleton for the project. The set was a flattened geometric abstraction of the architecture of SFMoMA, which is super graphical and kind of overbearing in some ways. Within this film production, the subject of the film was the role of speech and the performing subject. We worked with the philosopher and theorist Judith Butler as one of the main performers, as her work has been largely about performativity and subject-formation through the speech act—this was the conceptual linchpin to the project.

How did Judith Butler become involved in the project?

At the time, Judith was a local figure—she was teaching at UC Berkley—so we got lucky, and when we got in touch with her and she was interested in working with us. We worked during the open hours of the museum, and we had blocked out scenes and situations that we wanted to capture on film, so within that structure Judith presented a few different lectures based on a similar conceptual thematic, but they all were seemingly disparate subject matters like nationhood, Shakespeare, Freud, that kind of thing—all centered around the idea of the act of talking.

We would shoot her giving one part of a lecture, and then interrupt her, as any director would, to say, “Ok, let’s change the lighting, let’s take that again but with camera tow from over here; move the set around a little bit"—and then she would switch to a different lecture. So people were coming to the museum to see Judith Butler lecture, but they would never get a whole, linear, singular lecture. It was always interrupted, and she was always jumping from one topic to another; but if you listened to the whole thing, you would get the continuous conceptual thread running throughout.

Today Is Not a Dress Rehearsal

at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009

Today Is Not a Dress Rehearsal

at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009

So it’s also related to what we were talking about before—performative roles both people and objects. It’s about foregrounding the inescapable atmospheres of production. Obviously collaboration is key in these projects, too. Which leads us to New Humans, the collaborative moniker under which your work with other artists is presented. Why use a separate name for those projects? And, since they’re clearly distinct ways of working for you, what are you able to do in collaboration that you can’t do when you’re working on your own?

It’s a way to work with other people in ways that I can’t work by myself—for example doing music, or making a film, taking photos, that kind of thing. Because I make objects, I think of myself as a sculptor; I work with space and how we’re shaped by our built environment, how objects dictate our experiences. The collaborative work came out of me thinking about how to demonstrate the other possible identities of an artwork. For instance, take the double-sided painting panel wall. Yes, it’s a painting, but it’s also a sign board; it’s an architectural element that delineates a kind of work space or work environment. Demonstrating these multiple roles, that’s how New Humans comes into play—it’s a cubicle, but it’s also an isolation booth for recording sound, or it could be a set for a photo shoot, if you invite a photographer and models, or whoever, to work with it.

That really comes across in the videos, of which there are a couple up on Ubu.com, that are partially documentation of musical performances, but they’re also partially documentation of the cubicle pieces as sculptures. Then there are also visual effects happening on top of the video. There are a lot of different layers happening at once.

I like the idea that the object in an exhibition isn’t the end of a process, it’s a starting point for other things. The project becomes more than just the painting—it becomes an ephemeral moment that happened, a video that comes later on, or a soundtrack, or whatever. So many things come out of the production process. It’s a way of complicating the whole idea of the project, itself. Some people are like, “Well, what’s the real artwork then?” And that’s the question, I guess. But it’s not one that troubles me.

After the Martini Shot

at the Seattle Museum of Art, 2011

After the Martini Shot

at the Seattle Museum of Art, 2011

So how do you move your work forward? How do progress within this very open idea of artistic practice?

Right now, I’m working on a solo show, "Total Body Conditioning," for September at Art in General . I’m going to be showing new works, which are essentially jacuzzi paintings—they’re actually thermoformed clear acrylic tub shapes that get spray-enameled, so they’re hybrid painting-sculpture objects. The form is sort of like where figuration meets abstraction: the human figure is physically implied in the form of the bent acrylic that makes the seat inside the jacuzzi. But these are turned vertically upright, so they’re like a new version of my “Furniture Art” Plexiglass paintings. The jacuzzi is a nice metaphor for this idea of health and leisure time and socialization in this object.

The opposite of a cubicle, in a way?

Right, but in some ways also very similar, because the company, Jacuzzi, that invented this hot-tub form, started out as an aerospace company. They invented a water-jet hydraulic pump, which they then realized had applications for hydrotherapy—conditioning the body. You could use this technology from aerospace—also military—in hydrotherapy, which is for your health and to the benefit of the body. So they invented this tub form that dictates how, if you’re of a certain economic class, you would spend your leisure time, and how it would benefit your health and potentially make you a better worker, too.

And the new works are freestanding, like the Herman Miller panel pieces?

One will be freestanding and one hangs on the wall, like a painting. There’ll be a group of new "Furniture Art" Plexiglass paintings, and some more woven acoustic paintings using audio that I recently recorded in Japan. I did a global residency through Creative Time , and I visited a few Toyota factories. Toyota actually built their company on industrial power looms, in the 1920s, before they realized that their “product” was actually mechanization, itself. So they could apply their production methods to making cars, or prefab homes, or anything; they’re famous for cars now, but they still make power looms and prefab homes, etc., all based on these same autonomation production processes. So that recorded sound is going to be made into the next series of woven acoustic portraits.

Installation view of Mika Tajima's

A Facility Based on Change

at Eleven Rivington, 2011

Installation view of Mika Tajima's

A Facility Based on Change

at Eleven Rivington, 2011

It seems like the newer work is moving onto the wall, maybe in a reversal of what you normally see—an artist starting with painting and becoming more sculptural, expanding into space. It’s interesting that you’re going the other direction.

Actually, the wall has always been an element in my work and projects. It's a matter of foregrounding and backgrounding that’s at play. Whereas some works focus on the performers and actions in front of the objects, I am now also looking at what comprises the scenography. This includes walls, painting, sculpture, prop, furniture, and décor and their possible transformations and how the body is implied.

I’ve used the original Balans Chair, by a Norwegian designer named Peter Opsvik, in several shows. I like including them because they allude to the human body, but they also actually shape the human form into the chair’s own form—rather than the chair conforming to us, we conform to the chair. The whole idea of ergonomics was to have the human worker be more efficient, to be able to work longer, to stay in one place longer. Now there are all these new, evolved versions of these chairs—they look like kangaroos, with weird tails that come out—there are even some that recline, or ones where you’re not even sitting anymore, you’re walking; you walk or stand at your desk. It makes you wonder if we are adapting or coping.