It’s no accident that the Metropolitan Museum of Art unveiled its new website just a day before it inaugurated the Met Breuer. The Met’s newest branch is the clearest manifestation yet of its conviction that as encyclopedias migrate online, so must encyclopedic museums—and, eventually, all museums.

At the press preview, the museum’s Modern and Contemporary Art department head Sheena Wagstaff spoke of the Met’s “responsibility to both disrupt and expand” art history. Both of those Silicon Valley-inflected objectives have been pursued for a while now at metmuseum.org , where the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (itself relaunched in January, and now accounting for about 40 percent of the site’s traffic) presents visitors with images of some 7,000 art objects to scrutinize, share, or arrange in innumerable configurations.

At the entrance to this online portal, you might find C é zanne’s seated peasant next to a 15 th century medieval scepter and a Monet above a North African wall hanging. Distinctions between art and design objects, celebrated and unknown makers, are done away with—not always for the better. Questions remain about what kind of engagement, exactly, the Met is promoting, as does a musty whiff of the 18 th -century curiosity cabinet. But it’s worth noting that “Modern and Contemporary Art” is just one of the timeline’s 13 thematic sections; so, for that matter, is “European.”

Overall, the relaunched website is designed to give “equal prominence across the Met’s three locations” (Fifth Avenue, the Breuer, and the Cloisters) with digital constituting a “fourth space,” in the words of Met director Thomas Campbell. It also elides previous distinctions between the desktop and mobile sites, encouraging art lovers to think of offsite browsing as part of the essential Met experience and to navigate the galleries with phone in hand (if they weren’t already doing so).

Titian's

The Flaying of Marsyas

, probably 1570s

Titian's

The Flaying of Marsyas

, probably 1570s

The first shows in the Met Breuer's new galleries extend the logic of the website into physical space. That’s especially true of “Unfinished: Thoughts Made Visible,” a digressive exploration of art from the Renaisssance from the present made by artists who, for one reason or another, stopped short of completion. It’s as much a mission statement as it is a temporary exhibition. As Wagstaff told Artspace , “the format of a show like ‘Unfinished’ that covers a broad span of art and history will be a feature of the program going forward.”

The delights, and hazards, of this digitally-influenced strategy unfold over two floors of the Breuer. First, the hazards: the sheer breadth of the topic makes the show feel amorphous in places, more like a permanent-collection display than a tightly conceived group show. This is especially so on the fourth floor, where the show’s most modern and contemporary works are occasions for accessible but rather rudderless musings on infinity (Pollock) and entropy (Smithson) that prove as unwieldy as the idea of “unfinished” itself. There are as many ways to leave an artwork unfinished, it turns out, as there are to make one.

Robert Smithson,

Mirrors and Shelly Sand

, 1969-70

Robert Smithson,

Mirrors and Shelly Sand

, 1969-70

And visitors may be surprised to discover that linear chronology still holds sway, for the most part, in the installation. When it doesn’t, the risks become clear: putting a massive, Cézanne-inspired Luc Tuymans still life in the same room as several actual Cézannes, as “Unfinished” does in one of its few chronological mash-ups, has a way of underlining just how overvalued (from a market perspective and otherwise) the contemporary has become.

The delights, however, are abundant and often unexpected. One, which should have been obvious but was largely absent from the pre-game commentary, is a parade of the kind of loans only the Met can pull off. (The introductory gallery has not one but two immense Titians from European collections, including his Flaying of Marsyas , from the Archiepiscopal Palace in Kromeriz). Another, laced throughout the show, is a deeply philosophical and even connoisseurial conversation about art-making, one that’s led by artists rather than curators. Staring at Dürer’s ghostly underdrawing in Salvator Mundi or Richter ’s smeared Stag or Mondrian’s New York City 2 with its tape lines and pushpin holes, you’re reminded that in any discussion of the “unfinished” the artist has the last word.

Albrecht Durer's

Salvator Mundi,

ca. 1505

Albrecht Durer's

Salvator Mundi,

ca. 1505

This idea of an artist-driven museum (reinforced by Kerry James Marshall's succinct speech, at the opening, about all art coming from other art) also connects to Met’s digital strategy via its web video series “The Artist Project,” which dispatches contemporary artists through the halls of the Met in search of inspirational works. Older art can be a crutch used to prop up the contemporary, as anyone who’s slogged through artist statements or auction catalogs with dutiful historical asides can attest. But it can also be a spark, or a kind of code-breaker, as we see often in the “Artist’s Project” and in the Met Breuer’s intimate pairings: Willem de Kooning and Maria Lassnig , El Greco and Thomas Hart Benton (an association made only in writing, on the label for El Greco’s monumental, roiling The Vision of St. John , but nonetheless a relevatory one).

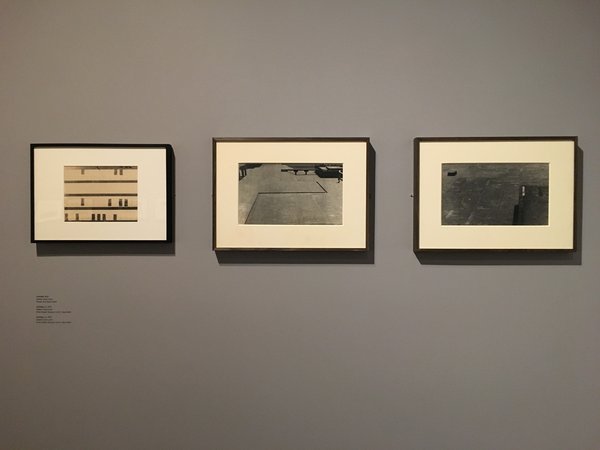

As the art historian Hal Foster told the New Yorker recently, the Met Breuer is “exactly what New York needs at this moment, when there’s such a stress on presentness and the fascination with ‘now.’” All the same, the Met Breuer is relying on performance and photography, two very “now” parts of art experience, as vital connective tissue in the historical-contemporary continuum; this extends programs already underway in the main Met building, where Limor Tomer has been orchestrating the “MetLiveArts” series of performances and talks in the galleries. The other inaugural offering besides “Unfinished,” a solo exhibition of the Indian modernist Nasreen Mohamedi, is accompanied by music composed for the occasion by the Met’s resident artist Vijay Iyer; it also emphasizes Mohamedi’s photography as “visual note-taking,” a way of linking disparate sources of inspiration from her travels and an activity that's familiar to the Met's one-million-and-counting Instagram followers.

Untitled Gelatin Silver Prints by Nasreen Mohamedi, 1967-1972

Untitled Gelatin Silver Prints by Nasreen Mohamedi, 1967-1972

We’ll have to see, in the eight years of the Whitney lease and possibly longer, just how the Met Breuer fits into New York’s ever-more-competitive museum landscape, and how it redefines our cherished relationship to the Met itself (a process less fraught, one hopes, than the release of its new logo). Our relationship to images, art objects, and the museums that house them is changing all the time. When the Met’s takeover of the Breuer was first announced, it sounded audacious; right now, it feels as if it was inevitable.

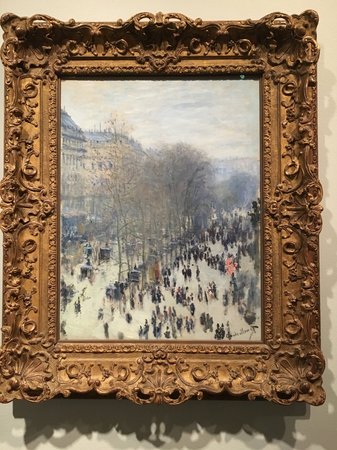

What is clear is that the Met, online and off, is making it easier to discover the art we don’t know and returning a sense of urgency to the art we do know. A quote on a label in “Unfinished” from the 19 th -century critic Ernest Chesneau, writing on Monet’s Boulevard des Capuchines , seems apt, both as an echo of excitement and a reminder that the now-unfashionable Impressionists were once the very height of "contemporary": “Obviously, this is not the last word in art, nor even of this art.... But what a bugle call for those who listen carefully, how it resounds far into the future!”

Claude Monet's

Boulevard des Capuchines

, 1873 or 1874

Claude Monet's

Boulevard des Capuchines

, 1873 or 1874