Since Art Ranklaunched in February 2014 under the impish name Sell You Later, the site has been the subject of enormous interest and fervid speculation in the art world. Known for placing emerging artists in pitiless categories like "Buy Now," "Sell Now," and the dreaded "Liquidate," Art Rank purports to reveal the kind of closely guarded information that was once traded in the shadowy back rooms of galleries. It promises, in other words, to throw open the windows of the art market and create a climate of radical transparency.

The site's 28-year-old founder, the Argentine-born Los Angeleno Carlos Rivera, comes from a gallery background himself. He learned the tricks—and inefficiencies—of the trade at his short-lived West Hollywood space Rivera & Rivera. He then opened an art fund on behalf of a tech-industry client, devising a form of data-driven analysis to guide his purchases. Beginning with $700,000, the fund ballooned to $12 million before being sold.

Now, Rivera has taken his number-crunching approach public through Art Rank. The company acts as both an art-market analyst (with shades of Jim Cramer's sweaty-browed gusto) and a sales floor, selling artworks by rising market darlings three times a week through its "Buy Today" flash sales that appear in subscribers' inboxes on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. ("Buy Today" is currently on summer hiatus.) Rivera also offers a limited number of subscribers who pay $3,500 per year advance access to Art Rank's data, ostensibly giving the flippers among them an edge on the competition.

Has Rivera succeeded in finding the profit-minded collector's equivalent of the Holy Grail, a financial model that can be applied to the notoriously subjective, fickle, and high-flying art market? Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the entrepreneur about what, exactly, he's trying to accomplish through Art Rank—and why he thinks it's only a matter of time before government regulators come down, hard.

RELATED LINKS:

Carlos Rivera on the Truth About Art Rank’s Grand Data Play and His Newest Disruptive Business

How did you first become involved in art, and what was Rivera & Rivera gallery? What year did you open it?

The question of how I became a gallerist has a long-winded answer. I went to USC for film and business and I was graduating in 2009. A lot of my classmates were going on to unpaid internships, which was a ludicrous concept after having spent $300,000 on an education—it didn’t seem rational to me. So rather than accept that path, I decided to look at things from a far more analytical perspective, and, given that perspective, it seemed to me that 2009 read very much along the lines of the economic climate of the 1980s, when coming out of the recession there was a thirst for tangible assets like silver, wine, art, gold, and other collectibles.

Of these, art interested me most, and it also had the particular advantage that it could be consigned, since I didn’t have a million-dollar nest egg to go and buy gold, diamonds, or cars. With art it seemed like there was an opportunity to consign work and become an art dealer in that way.

It also seemed like a valid point of entry in that it wasn’t a red ocean, it was a blue ocean, in that there weren’t that many people competing in the space due to the heavy losses that the galleries sustained to stay operational during the downturn with overheads of, say, $50,000 per month, without being able to sell anything. So here was an opportunity to open a business in the black, whereas all these other galleries had been in the red for years. It gave me a strategic advantage, I would say.

Also, because real estate had suffered greatly during the recession, it was very easy to approach these mixed-use residential developers and tell them, “You’ll have trouble filling your residential spaces if you have the blight of your commercial vacancies on the ground floor, so I’ll partner with you and give you a 50 percent share of the profits if I can take over the space and put in a gallery.” Several developers in downtown Los Angeles near USC were receptive to this, so I got a great space downtown that I didn’t have to pay any rent on. If I sold a work of art I would pay the developer 50 percent of my profits.

It literally took $10,000 of minor improvements to open 4,500 square feet. It was easy to get started, because there were some artists that interested me and interested some art collectors that I had met along the way. And my proposition to the collectors was very simple: I will buy art on your behalf at my cost if you give me money to do so. There was no profit for me, but I was showing up at these artists’ studios and buying art for these collectors on the premise of, “Hey, I’m the first person buying art out of your studio in the last year or two, so after this you’re going to sign with me.”

So I was able to establish a roster relatively quickly, and I was also able to establish a very loyal collector base. Within a year the gallery became a profitable enough endeavor that I ended up moving from downtown Los Angeles, which wasn’t the hub then that it is today, into a beautiful Arata Isozaki space on Robertson Boulevard in West Hollywood.

What kind of artists did you show?

I showed a fairly wide range of artists. At the time there was a lot of interest in street art, so there was an artist named Retna who I showed, along with a number of other California artists. As soon as I moved to West Hollywood, though, I also began showing a lot of postwar material, everything from Rauschenberg to Twombly to Ed Ruscha. So my gallery changed dramatically, and my clientele did as well. This was 2011 and there was growing interest in art, so this was no longer just a prognostication that the U.S. art market would do well and that it would be a buyer’s market. There was a sense of that on a global scale as well.

What did your experience as a dealer teach you about what collectors are looking for?

I had collectors who were seeking to capitalize on the buyer’s market of 2010, 2011, more than anything else. These are people whom I had informed it would be a beneficial time to buy art. You could buy Twomblys for $1 million and you could buy good Ruschas for $2 million, and obviously that tide has changed dramatically. So these were people who were seeking value. Clearly, in terms of seeking value you also seek that which makes you content and which emotionally connects with you, but these collectors were, for the most part, seeking objects that would maintain or create wealth.

Were they mostly California-based collectors or were they from a broader geographic spread?

They were both. I had a lot of international collectors, and I had a lot of California collectors. You know, Los Angeles has never really been a prime hub for collectors, and certainly that era was no different. When I closed my Robertson space it was for a multitude of reasons, but chief among them was that I think I went six months without a single person stepping foot into the space who actually converted into a sale.

So, a lot of people came to the shows and we threw a mean party and our dinners were unlike any other, but in terms of people actually coming in and viewing the work and buying it, that’s not how it went. The people who did buy would buy over email without ever seeing the work—they were completely comfortable buying from jpegs—so, in the end, it didn’t make sense for me to have a $30,000-a-month overhead.

Were your collectors the same kind of people who were collecting from blue-chip galleries like Blum & Poe, or were these a new class of collectors who were coming at art via a different route?

I wouldn’t say that it was an entirely new breed of collector. It was both. There were certainly some collectors who were traditional and sought relationships with galleries and were buying from Gagosian and Blum & Poe and some of the smaller outfits out here in L.A. like Patrick Painter. I would say that it was not a completely different sample set of collectors.

After you realized that you weren’t able to monetize your gallery space and turn foot traffic into buyers, what happened to the gallery?

As I said, there were a couple of reasons why I closed the gallery, and one of these was that the physical space had no true bearing on the sales I made, but another one was that one of the collectors whom I had bought a lot of work for during this time basically said to me, “You’re an okay gallerist, and a great advisor. I think these talents would be better put to work if you did something like an art fund.” So he gave me a seed amount of money to do an art fund on his behalf, and that’s how it started. I found it was easier to have an art fund without a gallery.

Was your backer a known collector? What can you say about him?

He wasn’t a known collector, he was a tech guy who had a large liquidity event and sought to put his cash to work.

So how did you go about building the fund?

When I was approached with this opportunity, I didn’t want to go about it in a traditional or subjective way. I’ve never sought to do things in the ways that others have established to be normal, and there’s this idea when you’re an art advisor that Alex Israel is doing god’s work because you’re friends with the guy, and that David Ostrowski is the most important artist on the planet because you have a relationship with Javier Peres. These are all very subjective relationships, and while I understand human nature and why art advisors advise in the way they do, I had always imagined that it would be most important to advise someone based on some kind of objective measure. And these kinds of objective measures didn’t really exist in the art market.

If you look at Marion Maneker or Artnet or any of these guys who do analysis of the market, they’ve always done it based on a momentum ideology. So that means they say, you know, “Parker Ito sold yesterday for $5, it sold today for $10, it’s going to sell tomorrow for $15.” And that’s unintelligible. If you put that sort of reasoning in front of any hedge funder in terms of a stock trade, your things would get packed that day and you’d be escorted out of the office. It’s an unintelligible strategy when it comes to any kind of financially minded investment or, for that matter, any kind of decision-making, and that’s the kind of reporting and market analysis that’s been out there: “These are the auction results for Sterling Ruby today, and here’s what he’s going to do tomorrow.”

The problem with auction results is that they’re only really determined by S&M: sentiment and manipulation. Neither of those are truly intrinsic underlying variables that could tell you what the future of a market might be. So when you’re an intelligent investor, say, Warren Buffet, you’re not looking at Apple’s stock price and saying, “It’s $700 today and was $600 yesterday so it’s going to be $800 tomorrow,” you’re going to look at the intrinsic underlying variables to see whether that business is worth $800 tomorrow or $300 tomorrow. And no one had ever really done that.

So I really wanted to approach my art fund based on the underlying fundamentals. People often forget that the art market is a market like any other, and supply and demand lead to equilibrium. So a record result isn’t always a good thing—a record result is the reason why Seth Price works have flooded the market, and just because one work sold for $785,000 at Christie’s doesn’t mean that the next work is going to go for $1 million. First of all the works are priced on margin, and second of all, record demand leads to record supply, so the equilibrium ends up downward, and now Seth Price works are worth a lot less than that one result. That’s because, for a lot of people, the potential of $750,000 is worth a lot more than having a Seth Price on their wall today.

All of this is to say that there are underlying variables of objectivity that are difficult to measure in the art market, and distilling what those are was the first challenge. So when thinking about supply and demand, a few of the most important variables you might want to think about are: How many works has an artist created this year? In what hands are these works? What are the proclivities of the collectors who now own these works to sell them at auction? How many of these works are going to become available? What collections are these works in, and how does that data predicate the future success of someone based on past data? So it’s complex trend analysis. Then you add in Instagram data, and Instagram data is incredible because you’re basically crowdsourcing opinion.

How would you describe Instagram data?

Instagram is the first time that the art world, and in particular groups of collectors, have congregated online. I think two primary vectors effectuate change in the art market, and one of them is interconnectedness. Today, that interconnectedness is most bound by Instagram. And today, ideas and knowledge are non-pyramidal. This is to say that it used to be Leo Castelli would tell his collector, “This Pop artist is going to be really important, and you need to buy him,” and that would be it.

I would argue that now the flow of information is far more distributed and goes in the other direction: a collector might walk into a studio, see something, Instagram it, and find that all of his other collector friends “like” it, which then brings it to the attention of x curator, leading it to end up in the Leo Castelli of today’s gallery. So it’s completely inverted the structure of information. But in terms of putting weights on a “like,” it’s difficult; you have to qualitatively assess what the value and saliency is of Alberto Mugrabi or Anita Zabludowicz liking something on Instagram.

A lot of this is challenged by something that has generated a lot of the controversy about Art Rank—a general disbelief that you can somehow quantify art. I’m of the generation that believes everything can be quantified. With the amount of data we have today, absolutely anything can be quantified.

It seems like the data can be quantified, but aren’t there more intangibles in the value of an artwork that can’t be quantified?

Absolutely. This is one of the distinctions that exists: there’s price and there’s value. There’s nothing to say that Art Rank can truly tell you what the value of a work is so much as I can tell you what the effective market price of an object is. I’m never saying that something is good or bad.

If Art Rank tells you to “liquidate” Sterling Ruby, it’s not because I don’t think Sterling Ruby is one of the important American artists who will be around in 30 years. It’s because in 2013 you should have sold your Sterling Ruby for $1.3 million dollars, because of the opportunity-cost burden of not having done so, because today you can buy a Sterling Ruby spray-paint painting for $600,000. You could have sold one then and bought two today and who knows what other works you could have bought in the interim and made more money on. So, if you’re looking at it with a financial mind, it certainly makes sense to factor in opportunity costs.

Let’s go back to your art fund for a moment. So you started the art fund with money from your tech-industry backer, and you began to try to extract data from the social milieu of the art market. You brought on some people to help you, is that correct?

I did. I brought on a data scientist and a financial engineer.

What happened to the art fund?

The art fund did well, and since then I’ve had a few art funds and they’ve done well, too. It was an interesting experience. I think that, for people interested in getting into art funds, the two most difficult aspects of an art fund are access and horizon. So, if you’re successfully able to raise an art fund today, the first question is, “Will you be able to buy the right works for it?” and the second question is, “Will you be able to sell them without compromising your future access?”

Many people are considering art funds today, galleries are considering art funds, and everyone who is considering an art fund calls me to ask me about it. And, short of having an extremely savvy person to operate your fund, it’s not something I would advise anyone to do. I’ve established a particular way of doing art funds where I absolutely protect my clients’ investments, and I think that the way I do it will one day lead to a great amount of controversy regarding tax donations and will change the conversation about how art is considered a financial object, not in the sense of sales but in the sense of donations.

Was your first art fund a single-investor fund?

Yes.

And you’re saying that the way you are running art funds is going to bring on more scrutiny from regulators. What is it about your approach to donations that might draw their ire?

Well, I think that the whole art world is going to bring on scrutiny from regulators, and I think that at some point the art world will deserve it because of the way that money is moved around. But, in terms of art funds, I think that using single investors is the optimal structure, because in the end if every single work that you acquire for an art fund doesn’t pan out you still have a stop-loss—you can still donate everything you bought for the art fund on behalf of the single proprietor who funded it and get most of your money back via the cash value of a donation’s tax shield.

So how did you manage to successfully dispose of the works in your fund?

It varies. I very rarely like to use auction houses—auction houses, to me, are some of the most inefficient dinosaurs of the art market. If you call Sotheby’s today, they’re going to put you in an October London sale, after which it will take you two to three months to get paid. So you do the math—if you consign on June 6th you’re not going to get paid until December. That’s six months. And given that I value the opportunity cost of any work, I don’t consider that waiting six months to get paid is ever worth the potential premium you might get by selling at auction.

I also feel that auctions are an irresponsible deaccession method, because as much as you might be able to attract a record value for a work, these values are always reported inclusive of the auction house’s 25 percent fee. Also, you can cause a run on a market, such that if I send a Seth Price to auction and I get $750,000 for it, then if someone else has six other Seth Price works in their closet they’re suddenly going to believe that theirs are also worth $750,000, and the market gets flooded.

So I always try to sell works privately through the many channels that I operate, and if I can’t sell something privately for the value I want to get for it then I end up donating it. In the case of Seth Price or someone like Christian Rosa, if there are three auction values that can be considered a fair IRS comparable at $750,000 and the most you can get on the market today is $250,000 or $300,000, then you ought to donate those works because the tax shield that you’re going to gain is greater than the cash value of what you could get from selling it.

Therein lies one of the flaws of the tax code, because it doesn’t understand the velocity of the art market. It understands the limited velocity of something like real estate in terms of those write-off laws, but it doesn’t understand that an artwork can both gain and depreciate in value exponentially very quickly. A lot of people take advantage of that. A lot of the big collectors in the world who thumb their nose at me and say I’m evil because I sell art—you know who I’m talking about—it’s funny because they take advantage of the tax benefits more than anyone else. This is the true endgame of the art world. Everyone who’s on a museum board knows this all too well.

What brought you from the horizon of that fund to starting Sell You Later?

That’s a funny one. I had been traveling the world after the exit of a recent fund and I read this article by Katya Kazakina in Bloomberg about how flippers were making 1,500 percent returns on artwork. Shortly after, a friend excitedly called to tell me, “I just bought a Parker Ito for $60,000, aren’t you happy for me? They were trading for $30,000 and now they’re at $60,000, and they’re just going to keep going.”

That’s when it really struck me that people didn’t really understand the market, just that they knew they could make money buying art. But the people who are the new entrants to this business don’t know what they’re doing at all—the best resource they have is the occasional article, like the Bloomberg article, and that’s the worst resource you could possibly rely on. Because, first of all, from $60,000 all of those Parker Itos are now trading for $8,000, and, second of all, that $60,000 valuation was only providing exit opportunities for the flippers everyone was trying to vilify. And that’s the funniest part of the whole business.

So, for me… I don’t know if I would call it a moral obligation, but I felt some degree of an obligation to tell people exactly how it worked—and that is to say that art is not linear, it’s cyclical. People often forget that. What rises goes down and then rises again. And there’s the fundamental investing error that investors see low risk when markets have reached their heights and high risk when markets have reached their depths, and that error is attributed to people not understanding the cyclicality of the art market.

I thought I could make this evident by publishing my list, which was very tongue-in-cheek in the beginning, and showing people that, “Hey, you shouldn’t be buying Lucien Smith for $200,000 or Parker Ito for $60,000, because the only person who’s benefiting there is the flipper. If you really want to make money in the art world then you should be doing the right amount of research to find those artists whose data makes them comparable to the data of successful artists in the past, and then you can directly be the patron of both an artist and a gallery.”

That’s funny, because Sell You Later, with its jarring language of “liquidate” and the rest and its anarchic tone didn’t seem all that altruistic at the time.

I think that was lost in translation, because the people who hated Art Rank in the beginning, before they understood it, were the artists and gallerists. But the true actual long game of those columns like “Sell Now” and “Liquidate” was to warn people that this is not going to continue. If you look at the very first Art Rank, it looks prophetic—it tells you exactly what has tanked today, because the sentiment and manipulation surrounding it was too great.

You say you started the site as a lark. I’ve always wondered: was the name “Sell You Later” a “Simpsons” reference to Nelson Muntz’s immortal catchphrase “smell you later”?

[Laughs] It was. It really started as a lark, because all this information that I had… I could see it, and it was actionable for me, but it was very clear that other people didn’t understand. Other people were looking at this market and didn’t know where to enter, where to exit, what was what. There’s very little actionable market information available—it’s a true information asymmetry. I envisioned just posting Sell You Later as this funny thing. I didn’t envision people clamoring for it as they actually did. I remember asking my girlfriend, “Do you think Sell You Later is a good name?” And she said, “I think that’s fucking terrible.” [Laughs]

So that was that. I know how to code, so I coded it in a couple of hours and posted it online and created an Instagram account and put a subscribe button on the site. On the first day, it grew in a way I’ve never seen anything grow, and by the end of the first week I remember that our subscribers included 12 billionaires. And I remember, having had a gallery on the most expensive street in Los Angeles, how expensive and rare it is to get in touch with these guys. If the lifetime value of having one billionaire is $1 million, what would be the lifetime value of having a stream of billionaires?

It was a big deal, and I realized something important: there’s an intellectual capital associated with being the first in something. Some people seek that out through angel investing by going on AngelList and seeking the next Twitter—because no one is proud of investing in Twitter once it’s a public company; people are proud of saying they invested in Twitter when it was in the seed fund. That same sentiment is found in the art market. When you walk into people’s houses, they’re very proud to tell you that they bought a Mark Grotjahn for $5,000, not $6 million.

So it struck a particular chord, and it’s interesting that there’s a strong precedent for prognostication around any market, beginning in 5,000 BC when the Sumerians were the first civilization to truly invent agriculture. The first step was to invent it, and the second step was to prognosticate crop yields through weather and climate data. Prognostication is the first immediately perceived need of any market, and, yet, this in no way existed in the art market.

If Sell You Later was at first a goof, you refined the site and made it into a serious business when you relaunched it as Art Rank. But there was a hiccup between its birth as Sell You Later and its rebirth as Art Rank, where you got into a contretemps with the collector and famed flipper Stefan Simchowitz. When I interviewed him a year ago, he said of your platform that, “If you look at the data, he just doesn’t have the real data… the real data is unquantifiable,” and said that your rankings simply relied on “a scraping tool that analyzes certain people’s Instagrams to see which artists they’re looking at and which artists get liked.”

He said he called you and you apologized for taking his data, and then you posted a statement saying that “After a conversation with Stefan, we’ve agreed that SellYouLater was a disrespectful tone for this analytics exercise. It is impossible to gauge cultural value in objective terms as is evidenced by some of our past inaccuracies…. We will aim to achieve a more respectful and accurate index.” What happened in that encounter with Simchowitz?

In terms of scraping Stefan’s Instagram data, yeah, sure, he was one of hundreds of people who we followed on Instagram. So I’ll give him that credit. But it was really a realization that it was a more serious endeavor—that people actually wanted this data, including very serious collectors who understand the need for this kind of resource but don’t have the time to track every artist who’s coming up in the Post-Internet movement, or the resources to track every other important movement that might be coming up and so forth. So I knew it could be something serious, and it couldn’t be something serious under the name Sell You Later. And we never abandoned Sell You Later—it’s still our Twitter and Instagram handle—and I still get a laugh out of it, which is what’s important to me. I’m a selfish guy. [Laughs]

Now, when people sign up for Art Rank today, they don’t have much knowledge of what Sell You Later was—and that’s good, because we get a lot of very serious collectors. One of the things I’m most proud of in terms of our exercises with “Buy Today” is that we realized that a lot of people who follow us are in Asia, and I’m gratified by the thought that we’ve opened up large swaths of Asian collectors to the emerging market. They just didn’t have the actionable information before to be a part of it.

That’s a large part of what I’ve always wanted: I want the market to grow. It’s important that the market not just be a bullshit, elitist, “I’m-a-museum-board-member,” “I’m-so-and-so’s-son” thing. You need the art market to grow its pedestal in order to have sustainability, and people forget that. Or maybe some people just don’t want newcomers to be a part of it, and I’m averse to that kind of ideology. I think the art market is for everyone.

What were the “past inaccuracies” you mentioned in your Facebook post?

Regarding past inaccuracies, there was a moment when we considered that the objective data had to be subjectively weighted in order to reduce error. Since placement on the “Liquidate” column doesn’t indicate the lack of longevity in an artist's career, the inverse is also true. Having an artist ranked in the “Buy Now” column doesn’t denote any measure of talent or merit, rather it’s just an objective measure of the relevant metrics. For a moment, we thought it would be better to filter out such false positives. In the end we didn't, and I believe that Facebook post was deleted, and we carried on operating with an objective research model.

I was also convinced by numerous people that it was a major mistake to have a column called "Purgatory," which is now gone. As with any data-driven analysis, many of our data sets are rendered inconclusive—they neither tell you to buy nor sell. Given my Catholic upbringing, I know purgatory as not having a negative connotation but rather as a place "in limbo," and purgatory sounded quippier than "inconclusive data."

Okay, let’s dig down into the data behind Art Rank a bit. What spectrum of variables are you looking at when you’re extracting your data, and how do you weight different forms of information?

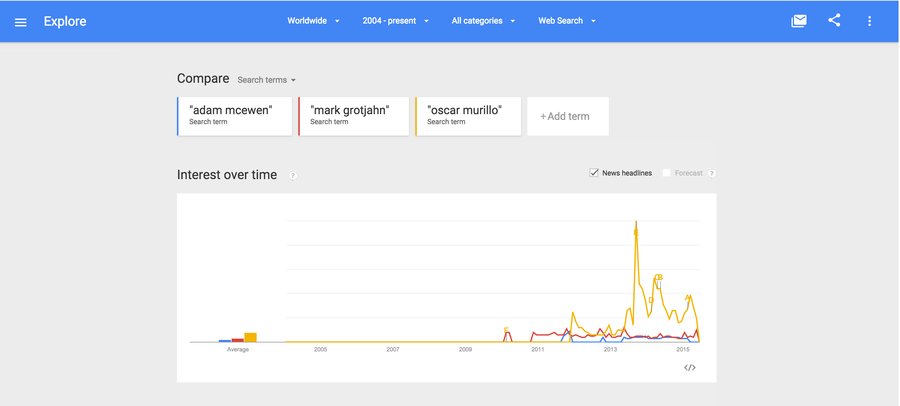

On a very topical level, there’s a little bit of disbelief about what can be done with data. But let me give you one small example. Here’s a chart that I want you to consider, and it’s just that—a mere consideration. A microcosm of what can be done with data. It’s something called Google Trends, and it’s really amazing—it can accurately predict when flu season will start, where it will be, and many other things, like elections. It’s one of the tools that Nate Silver uses to predict anything. All it’s using is search data to know when certain factors have reached an effective frequency and become relevant. We live in this age when Google can very accurately give you statistically relevant examples of interest in anything, and certainly artists are among them.

So this is a graph of three artists on Google Trends: Adam McEwen, Mark Grotjahn, and Oscar Murillo. I chose these established artists, because with younger emerging artists there often isn’t enough general search volume to be able to track them—if you used a younger artist, like Calvin Marcus, it would tell you that there’s actually not enough data to conduct a comparison, since the number of searches for him today might have only been around 30. But with the artists I selected, they have enough searches that a pattern emerges.

If you look at Oscar Murillo, the kind of attention he got is completely inorganic—it tells me that there’s something very real there, and there’s seemingly a head-and-shoulders pattern developing along with a well-defined trend line that would seem to suggest a sustainability that hasn’t yet found a plateau. Mark Grotjahn is certainly there as well, though with a much more sustainable career drive, and someone who isn’t there is Adam McEwen.

For me, Adam McEwen is the model of an artist who, while I enjoy his work, just hasn’t achieved that level of sustainability. His attempts to reach a plateau or a positive trend? They don’t exist. What you see are merely peaks that occur around each of his shows, and that’s it. So just using this data, if you’re wondering if you should buy an Oscar Murillo or an Adam McEwen, I can very easily tell you to buy an Oscar Murillo because there’s more evidence here as to the sustainability of that career.

And I should warn you here to ignore the very end of the graph—Google Trends for some reason changed the output recently, and it always shows all trend lines going to zero. But that sort of Google search data is something you can use, and we’ve found a way to use that data on a granular level, which nobody else does. We can actually track search volume down to zero searches. So with every single artist who we’re tracking—which amounts to about 1,000 emerging artists at any given time—I know exactly how many people in the world are searching for them, down to the zero number, this morning, this afternoon, and where. I can assure you that absolutely no one else tracks such information, nor probably could afford to collect such data.

Aside from Google search and Instagram data, can you elaborate on the other variables you factor into your rankings.

We utilize data including Internet presence, auction results, market saturation, market support and CV data—education, representation, et cetera. In service of preserving the accuracy and minimizing the manipulation of these inputs, we do not provide further specificity.

Stay tuned for the second half of this interview, in which Rivera reveals where the artworks he sells come from, why they're nearly all abstract paintings, and where the art market is headed.