It took a while, but the tide of Internet-enabled disruption that has swept through every other cultural industry has finally reached the art world. The sacrosanct traditions of the white-glove market are experiencing a profound shakeup, and without a doubt one of the most radical exponents of these changes is the Los Angeles-based entrepreneur Carlos Rivera—founder of the emerging-artist rating site Art Rank.

One key to Rivera's success has been harvesting reams of data on artworks, despite the sentimentalist’s avowal that art is unquantifiable; another key has been his zest in pushing the money that has always hidden behind the art into the spotlight. Rivera is now taking that approach to the next level with his newest business, Levart, which just launched yesterday.

In the second half of our two-part interview, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the digital insurgent about his sweeping approach to gathering data, why the new era of the art market belongs to the amateurs, and how Levart is going to level the playing field.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Art Rank Founder Carlos Rivera on Why He's Leading the Flipper Revolution—and Why It Can't Be Stopped

Can you recap in simple terms the varieties of data you use to drive your rankings?

It’s hard to convey a lot of the data simply, but in terms of Internet presence Instagram is a big one, and our Instagram analytics are rather robust. We track likes and hashtags, and the saliency of each of those. Saliency simply differentiates the importance of likes from relevant individuals in the art world versus those, of, say, a robot you hired to like your Instagram photos.

CV’s are also a trove of data. We look at auction results, if an artist has any. We’re also looking at whether they’re in institutional collections, and we’re looking at market saturation based on supply and demand—how many works are out there. Representation is obviously a big part, and so is education. So if I know that Christopher Wool went to Studio School and I know so-and-so other artist went there and now they’re both represented by Gagosian, and that before Gagosian they were both represented by Luhring Augustine… it’s possible to see a correlation there that could help determine a possible future trajectory.

Is it like a point system, where you apply a certain amount of points to CalArts, or a certain amount of points to having a solo show atthe Whitney?

They’re not points—though if it makes it more simple then, yes, we can call CalArts 90 points and we can call Harvard 60 points. But it’s a little bit more of a complex endeavor than points.

On your site you say that one of the metrics you use is studio output, as in the volume of each artist’s production. How do you do that?

We work with a rather large network of individuals in the art world, and we always have them report back to us, and everything they report back to us we report to the whole circle. In that sense, it operates very much in the style of an expert network. Expert networks are now illegal in the finance community, but they were incredibly helpful to a number of hedge funds. They’re based on the principle of crowdsourcing information, in that you can derive facts from a number of different opinions.

So we’re able to very successfully leverage that network of individuals into the index that we create, and, from everyone from advisors to collectors, we have a pretty good idea of how many works have been created—whether it's 350 Sterling Ruby spray-paintings or 300 Lucien Smith rain paintings or 30 Wyatt Kahn works per year.

Is this expert network made up of tipsters or is there something more formal? Are they compensated? How does it actually work?

Of the people who we use in our expert network, some are collectors, some are advisors, some are gallerists—it’s a pretty wide range. Everyone inside of our network gets information reciprocally before anyone in the public. You basically reward everyone for the information that they give you.

How large is the network?

It’s hovered at about 25 within the last year.

How broad a spectrum of art does your model apply to? Does it mainly apply to a certain kind of circumscribed area of the art market?

I don’t claim to have a completely robust model when it comes to, say, emerging artists in China. So it’s not an entirely global exercise. I don’t claim to have the best knowledge of emerging artists in South America or Africa either. I just don’t have a powerful information network within those realms. But in terms of Europe and the United States, then we’re looking at everyone from Carl Kostyál in Stockholm to Standard (OSLO) to New York galleries like Zach Feuer and everything in between. This is a cohort of artists that are existing within the most respected galleries in the emerging market today.

So I think that it’s a very good sample in terms of the nodes that consistently replicate—and that’s the art market. Things don’t move so fast that we could make Art Rank a daily exercise. There’s some velocity, but an artist like Aaron Garber-Maikovska has been where he is for quite a while and he’ll continue to grow because he hasn’t gone downhill and he’s not a blue-chip artist yet, so there’s not really another place for him.

Why did you opt to keep your focus exclusively on emerging artists?

It’s all meant to be emerging artists, because that’s the whole idea—we quantify the emerging art market. In business you’re meant to corner a niche and do it well before proceeding to any other. I would like in the future to include Asian emerging art, which I think is fascinating, and I’d definitely like to be able to tell people about the opportunities that exist in the blue-chip market, whether it’s with someone like Frank Stella or Larry Poons. But in terms of establishing ourselves I think it’s important to own the niche, which right now is the emerging art market.

You mentioned the cyclicality of the art market, and one funny thing is that the data on the Art Rank listings seems to jump around quite a bit. Just to give a few examples, Murillo, who you labeled “Liquidate” just last June, is now “Early Blue Chip.” Two artists that you presented as "Buy Nows" and even sold through “Buy Today,” Oliver Osbourne and Chris Succo, are now on "Liquidate." What is the longevity of your advice, and how do you believe your users can best act upon it?

The advice that we give has immediate actionability. So if you sold an Oscar Murillo in the beginning of this year, you could have gotten $300,000 or $400,000. Today, if you’re selling a 12-foot Oscar Murillo, you’re maybe getting $200,000 or $250,000 on the top side of the market. So it’s not to say that I don’t personally believe in Oscar Murillo, or that you shouldn’t buy Oscar Murillo, or that Oscar Murillo isn’t a great artist. It is only to say that there’s an opportunity cost foregone of being able to sell your Oscar Murillo at the top of the market. If you had gotten top dollar a year ago you could have today gotten two Oscar Murillos of the same caliber today. That’s some of the actionability of the “Liquidate” idea, and his metrics are such that he’s in the early blue-chip category because from here it seems that he will continue to grow, and it seems that at $200,000 he’s an artist who is worthy of investment.

What’s interesting about a limited timeframe for the actionability of Art Rank’s advice is that it really makes it most relevant for flippers who want to find an exit before the price goes down. In other words, the site seems to play to the “greater fool” theory of economics—the idea that there’s always someone out there who, if you time it correctly, will be eager to cash you out. How would you describe this outer ring of people—the buyers who aren’t privy to Art Rank—who can be flipped to?

God, I love this question. Flippers are just normal people. They aren’t in any way different from any art dealer, and I think people like to forget that. Flippers are merely amateurs. They do nothing different from what an art dealer does. Flippers buy something believing that it’s underpriced and they hope to one day sell it at a price that makes them money. That’s exactly what art dealers have done since the beginning of selling art. They’re professionals; these are amateurs.

It used to be difficult to be an amateur in the art market because there wasn’t information that allowed you to enter the art market without flying to Paris, without flying to New York, without visiting 20 galleries in Europe. Tools like Art Rank, like Instagram, allow you to research this inside information without having to go to 20 galleries, without having to know the curator at MoMA PS1. You might not have the ideal grasp, but you’ll have a good understanding of what’s what in the art world.

So, for the first time ever, these amateurs have been empowered in the art market, and, because the art world is an elitist place, there has been a vilification of amateurs. But amateurs are the reason that neutrinos are a confirmed discovery in astronomy, which is the greatest discovery of the past century, because amateurs and professionals collaborating were able to confirm something that could never have been confirmed by one professional alone working in a closet due to the hours necessary to be staring at a small patch of sky at an exact point in time.

This is all to say that the amateur revolution is something that has been enabled by the interconnectedness of the Internet, and I think that never before has the art market been as interconnected as it is today. And this professional-amateur relationship isn’t my own idea—it’s something that you see in every realm. Kayak.com, for instance, enables amateurs to become professional travel agents. And the different enabling tools within the art market include things like art fairs. Art fairs allow amateurs to meet a range of gallerists all in one day—it doesn’t require that you travel to each of these galleries and introduce yourself properly through a professional advisor.

So these flippers… I don’t see them as being evil people. I see many of them as being irresponsible in terms of their selling mechanisms, because they just don’t know better yet because they haven’t learned the ethics. But, as I’ve alluded to, it’s a self-cleansing process, because they’ll have access the first time, but they won’t have access the second time. So it’s something I’m not too concerned about, because once you’re outed as a flipper you won’t be sold to again.

I agree that there is nothing wrong in principle with anyone selling an artwork, and that the stigma of a collector admitting that they sold an artwork that they bought is ridiculous.

It all goes back to the elitism of the art world. If this were any other business whatsoever, the idea that amateurs would have a vested interest in this business wouldn’t be vilified. It would be respected, and tools would be financed to enable these individuals. It is only because the art world operates in the way that it does that everyone says that these people are evil. I believe that the future of the art market entails collaboration with these amateurs, either for production or distribution. Your question was, “Who are these flippers selling to?”—the quote-unquote “greater fools”—but the idea is that these flippers are bringing more people into the space.

They might be dentists in Arkansas, or small cliques of collectors in Minnesota and all these other little areas, and they are spreading the word by virtue of what they are doing—they have to train others to appreciate the artwork that they’re trying to sell. So they’re only growing the pedestal, and to vilify them is the most outlandish thing that anyone who is actually for the sustainability of the art market could ever want.

Okay, tell me a bit about Art Rank’s “Buy Today” feature. How does that work exactly?

There’s obviously been a great deal of misunderstanding about exactly what that is. First and foremost, I have sought to make good works easily available to people because I don’t believe there is such a mechanism in the art market today. Certainly there are some, but for the most part there aren’t a lot of great sites where you can click to buy artwork, and that’s disconcerting. Not only is that disconcerting, it’s backwards. I like the idea that you can come on Art Rank and buy great art with the click of a button without any degree of meritocracy—it’s about the first person clicking to buy something. That’s of my generation, and it’s how we operate. It’s welcoming.

How much traction have your “Buy Today” emails gotten?

The average click-through rate on our emails is 44 percent, so 44 percent of the people who are on our 40,000-strong list click on the emails. It’s unprecedented for anyone who has ever sent a mass email, and it’s because beyond buying it also provides readers with a window-shopping opportunity.

For us, it’s about collecting such information. I like to read the discrepancies between the different click-through rates for different artists, so if one artist has an abnormally low click-through rate it could mean that it’s a statistically relevant example of how many people might be interested in that artist.

Does that go into the cocktail of data that drives your rankings?

Absolutely. In the beginning we even published that data, because I thought it would be interesting for people to see what we were doing, but now we don’t anymore because I don’t need our competitors to know what our data looks like. But I also track exactly how many cart-adds there were, which to me is a layer of affinity, and I track how many people go the checkout phase and enter their private details, and lastly I see how long it actually takes for people to click the button to buy something.

So it gives us some indication of price sensitivities and accuracies, and it gives us interest level—it gives us a lot of information in the same way that any prediction market would operate. We’re always trying to make our algorithm and the data that we quantify more robust, and this is just one way that we do it.

The artworks you sell have been mostly abstract, mostly highly decorative, and mostly paintings. Only three artists you’ve offered through “Buy Today”—Danh Vo, Greer Patterson, and Artie Vierkant—can be considered sculptors, and even their works are wall pieces that look like paintings. What explains this trend?

Why are paintings the most liquid? In my opinion, paintings are most liquid due to the 1031 trickle-down effect. So if you have a Giacometti today and you sell it for $100 million, then you can keep your $100 million if you 1031 out of it. A 1031 exchange is where you sell an object and you replace it with any in-like-kind object—the tax code allows you to replace it without having to pay capital gains on it.

So if your Giacometti costs $1 million and you held it for x number of years and you’re selling it for $100 million, then $99 million of that is going to be taxed at the capital-gains level. That’s a huge amount of loss—you’ll be out between $30 million and $40 million. Whereas, if you 1031 out of a Giacometti you can go and buy an in-like-kind sculpture. Usually people don’t replace one $100 million object with another—usually they’ll replace it with a few others, let’s say 20 $5 million objects.

Now, the issue with Giacometti is that there aren’t that many $1 million-range sculptures, whereas there are quite a few $1 million-range paintings. So by virtue of the number of paintings of the $1 million-plus variety that become available at auction every year, you can imagine that that many works are also statistically representative of how many works will be 1031-ed into other paintings. And the in-like-kind clause states that I can trade a Picasso for a KAWS painting, because an oil painting on canvas is considered in-like-kind with an acrylic painting on canvas.

So I believe that there is a 1031 trickle-down effect on paintings. There might also be an emotional or sentimental response, but, strictly objectively, I believe that’s the reason why so much of what the market looks at is painting. It’s a matter of transitive property with the 1031 exchange.

But, even in that case, why does everything look the same?

Why does everything look the same? It’s very simple. It’s not about brand identity or curatorial opinion—we’re talking about a movement. People forget that everything operates in movements—nothing exists in a vacuum. The reason that dolphin art in Big Sur isn’t a hot commodity is that it doesn’t exist in any sort of relevant movement that you and I can specify as important. If the only filter you can apply to it is that it’s Big Sur art, then that’s a very specific niche that doesn’t apply to the rest of the world. Or, on the other hand, if you say that it’s decorative art, then that’s such a big niche that that one particular piece of dolphin art is irrelevant to the grander conversation of decorative art.

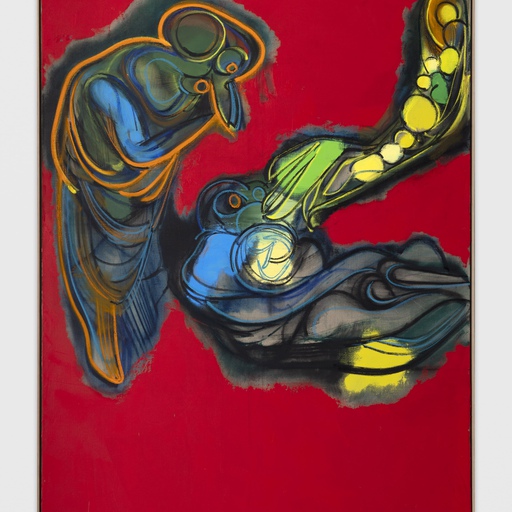

When you speak about a movement, like what we just went through with procedural abstraction, that’s what people are buying because that’s what’s relevant. What’s coming next is interesting. Feasibly, there’s a bit of a figurative moment that’s occurring right now, and for me the figurative movement is an important one, but it’s always sort of lingering, and I don’t think it’s particularly very different from any other figurative movement that has previously occurred.

So, I would say the next big movement is Post-Internet. It’s the movement that matters the most to me. When I was a kid I had a computer in my room—from my earliest memories I have a computer, and it has changed how I discourse with the whole world, and will for the rest of my life. The idea that any movement could be more powerful than one about my relationship with the computer, via Post-Internet art, is impossible.

So, to answer why a lot of the art world looks the same—it’s because it’s all a part of a particular movement that we’re now ending. And within that movement we have codified who the winners are. From Pop art you and I can probably name 10 people, and most people can probably name three people, that’s it—and for the longest time those people will be codified as the most relevant progenitors of that moment, period.

The artists themselves, meanwhile, are mostly white, mostly male—in fact only four of 45 artists were women. What accounts for that?

A lot of people have suggested that I’m a misogynist, that I’m only listing male artists. But it’s funny—if you took a count of how many CEOs in America are minorities or female, I think you’d probably land at a similar percentage. Because that’s the way it is. I don’t have a better reason for you. If I’m a reporter reporting the news, it doesn’t mean that I’m complicit with what’s happening in the news or that I believe in its message. Likewise, if you look at the million-dollar results at the recent auctions in New York, you’ll see that only three percent of them were attributed to females.

Why do people prefer male artists? I’ll tell you very simply. If there’s a strong tradition of male artists having been accomplished at auction—and I’m strictly looking at things from an investment perspective—then that would be one of my binaries in terms of selecting what I might buy: Is it or is it not male or female? Because there’s such a strong, rich historical precedent of males succeeding at auction.

That said, if you look at females on the Art Rank list right now, they’re probably actually statistically overrepresented compared to what the market is actually willing to accept, so that might be a fault of mine. But in terms of what we offer and what is out in the market, I think it’s just a physical representation of the data.

Where do you get the “Buy Today” artworks from, and how does your choice of those works relate to the site’s ranking system?

The artwork comes from a few different sources. It sometimes comes from galleries—galleries have recently discovered that the “Buy Today” feature is an excellent marketing tool, and that when we reach an audience of 40,000 people and speak eloquently about the art it sells very quickly.

Some come from collectors who like what we do. Because we’re not interested in the business of making money on these sales we’re able to do things like have a 72-hour turnaround. So if you consign something to Art Rank on Monday and we could sell it on Wednesday, if our schedule was still clear, you would get paid by Friday or Monday.

That’s unheard of in the art world. If you consign something to Paddle8, you’re going to wait four months from consignment to get paid, if you ever get paid, you know? The idea that we could get you paid in 72 hours… only the most golden of art dealers could ever offer that.

How does the “Buy Today” work from a consignment perspective? How do the proceeds get broken down between Art Rank and the client?

If we were selling things at high margins it would be a huge profit center, but the way it works now is that someone comes to us and gives us a net price that they want and we add on 12 percent, and that 12 percent covers our shipping costs and credit card fees. In the end we usually make between two and four percent on sales. It’s by no means something that we’re doing to make money. It’s by far a loss-leader, and it’s a good one, because in terms of the amount of data that we’ve been able to collect it’s probably one of the best utensils that we have at our disposal.

I’ve heard from several sources that many of the artworks sold through the site have been purchased by groups of investors, and that you yourself own a percentage of some of the pieces.

That’s pretty awesome that someone would suggest that there’s a consortium behind it [laughs]. And, certainly, I have sold some of it myself, and I consider myself a collector, and I’m very proud of the things I’ve sold on there. But for the most part it’s other collectors. I can say that in terms of consortiums and funds, I’d probably rather place things privately for numerous reasons.

What percentage of the “Buy Today” pieces have you had a financial stake in personally?

Looking at the works that we’ve posted on Instagram, I can count four works. It’s not that low if you look at it from a percentage perspective. But, for the most part, I think it’s a great selling mechanism for people who need to make money quickly. A lot of what I’ve owned I’ve sold just because I really need to know the market data and I could not get it from anywhere else.

It’s interesting, because financial regulations insist that investment banks maintain a “Chinese wall” between their research/analysis departments and their investment bankers to prevent the use of insider information. That of course doesn’t pertain to the art market. But isn’t there a conflict in the fact that the organization ranking the artists is also selling work by the same artists? What would prevent you from coming into a quantity of work by an artist and then pushing them to “Buy Now”?

I think it’s important to divorce the two. But how do you know I’m not putting everything on the index so I can sell it? Mathematically, it doesn’t make sense. If I’m selling 40 works a quarter, and I’m only outputting an index one time a quarter, and only 30 of the spots on the index would make you want to buy something, am I going to fill the entire index based on what I have for sale for the next six months? I mean, people who think that are giving me a great deal of credit, which I appreciate, but I don’t really have that much foresight.

If I were looking to maximize profits, I wouldn’t be charging the prices I do. A large part of it is pricing things such that I can gain an awareness of what the primary-market demand is—if I’m pricing things at an egregious secondary-market value over what they’re worth, then I don’t get a true index of what the demand is for the object.

What is your sell-through rate for “Buy Now”?

Not everything has sold—some things haven’t sold, but about 90% have.

Do you follow where the works end up after they are sold? Are they often flipped?

I know that a couple of works have reentered the market, and the people who bought them made a killing. But for the most part I think a lot of people really love the work and haven’t sought to sell it, so that’s good. I definitely see both sides of it. A lot of the work sells to Asia and they ask for us to store it here, which I assume is a little bit of a currency play.

How would you say this business compares to your former gallery business?

In so many ways it’s different. When I had a gallery I had to sell art—I had to get on the phone with people and convince them that something is good—and this is not about that by any means. This is about providing quality work at quality prices in order to collect data and giving people good service along the way. We have free shipping, we accept Bitcoin and credit cards, so most people who buy artworks end up getting a free trip on their miles out of it. It’s a cool thing, man. If I were an art collector, I would be using it. I can’t envision using anything better than it to buy art. People who have bought work from me have gotten their work in two days.

My initial idea was to use Amazon fulfillment and have everything crated so you could get an artwork two days after you ordered it through Prime. But pre-crating things created a consignment liability, because if something happened to a sale—and 10 percent of the things we’ve offered haven’t sold—then we would have to take in the object and uncrate it, so that would be more of a headache. But our shipping is almost instantaneous, and the fact that you can buy art with the certainty of a credit card’s guarantee behind you—that’s great. Such a process is unheard of in the art world.

So what’s next? Will you increase the volume of sales? Are you looking at a flash-sale model indefinitely?

No. The flash-sale model for me is an interesting one, but I do believe there has to be some degree of scarcity—sending emails every single day will change the number of people who actually want to interact with what we sell. If anything, we’ve considered scaling back to just two times per week because it increases the scarcity. It’s a double-sided sword.

You described “Buy Today” as a loss leader—so what is Art Rank’s profit center? Your $3,500-per-quarter early-access offering is limited to 10 subscribers at a time, meaning that it tops out at just $140,000 per year.

I’ve learned a lot from the “Buy Today” model about what people need, and one of things that people are often need is instant liquidity for art, for any reason. It could be that they need to make a mortgage payment, or they’re looking at a different work of art that they like better—I don’t care what the reason is, but in terms of servicing those collectors there hasn’t been an art-lending vehicle that caters specifically to this market. If you have $25 million in trust today, then you’re going to very easily be able to borrow against your $2 million Warhol, but the idea of liquidity for collectors who are collecting works under $1 million hasn’t really been attempted by anyone other than maybe a couple of pawn-shop companies.

But there’s no reason this specific niche shouldn’t exist for the emerging art market. And we now have a trove of liquidation pricing data that would allow us to tell people, “If you’d like to borrow 50 percent of the value of this work, we can give you that amount of money.” So this is why it helps to grow the market, because if somebody senses the liquidity of an object they will have more confidence in its value.

Is this a new business?

It’s a new business altogether, called Levart. It’s the fastest and easiest way to leverage your art collection. We're the only art lender with enough data to loan against emerging artworks, which is a unique advantage and one I hope adds to the sustainability of the markets we're engaged in. It is a useful alternative for anyone considering selling a work—we can loan any amount between $5,000 and $1,000,000 within a day.