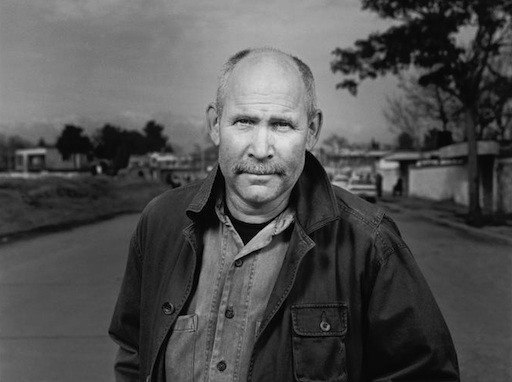

One of the most celebrated photographers working today, Steve McCurry is widely known for his richly colorful images of people and places around the world, notably Afghan Girl, a 1985 picture he took of a young refugee during the Soviet war in Afghanistan that galvanized humanitarian support for the region—and became the most recognized photograph in National Geographic's history when it was published on the cover. Other sites he has photographed include the temples of India and the smoldering wreckage of Ground Zero after 9/11. We spoke to the Magnum photographer about how beauty creeps into even his most harrowing pictures, his meditative approach to photography, and what he hopes people get out of his lyrical images.

What was it that first made you want to be photographer?

Actually, at first I just wanted to travel, and photography was a way to allow me to do that. But I was drawing and painting since I was 10 years old, so I've always been interested in painting and drawing, and I became interested in photography when I was 19. There's a contemplative or meditative quality to photography which I find to be a sort of peaceful state.

How did you become affiliated with Magnum?

Well, by the time I joined the agency I had already spent a number of years working and traveling. I had always admired the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, David Seymour, and George Rodger, and I wanted to photograph in that tradition—the humanistic documenting of world events and places and people.

For decades you have traveled the world covering conflict zones and places of suffering and poverty, capturing photographs that are at once testimonials of what you saw and compositions of surpassing lyricism and beauty. In your famous photograph Afghan Girl, for instance, the girl is clearly distraught and the photograph works as a journalistic document of the crisis, but at the same time the rich umber of her cloak, the piercing golden hue of her eyes, and the green background combine for an image that is ravishing and joyous in its beauty. What role does beauty play in your work?

I'm not sure I'm really looking for beauty. I might be looking for something, but I'm not sure that's the word that would define what I'm trying to portray or what I'm trying to show or what point I'm trying to make about what it is that I'm photographing. Take 9/11 as an example. I was just there in the same sort of place that everybody else was, and I think that there is a certain terrible beauty about some of those pictures, but it wasn't my intention to make it look this way or that way, I was simply photographing what was in front of me. I mean, take Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother—is there a beauty about that woman?

There's certainly a tough, rough-hewn beauty to that black-and-white portrait, and the composition is masterful. But there's something about your chromatic sensibility and the lush use of color in your work that is really striking. With those 9/11 pictures, for example, there's one image of a man covered in white ash with a bloody red mark on his head who is framed against a sky of crystalline blue. That picture is a pinpoint document of that tragedy, but it also seems to register with the viewer more deeply because of the symphonic hues. How does color come into play when you frame your photographs?

I never try to make my pictures about color—I'm more interested in content and narratives and story. Color obviously is something you have to pay attention to. It needs to be harmonious—I think you need a certain harmony in your pictures. But pictures that are just about color don't interest me as much as pictures about some human element. However, the world is in color, so it's logical that one would photograph in color. I mean, black-and-white is fine, but a lot of places where I work color's more integral to the culture, so to tell the story it needs to be in color. So that's partly it, but color's not my main preoccupation. It's something you need to consider, but it's not the main point.

How do you select the subjects of your photographs?

Well, I think you kind of wander through life and go to places that interest you, that you have a fascination for and you respond to, whether it's Tibet or Haiti. It could literally be anyplace. I just happened to like to travel so I find myself going to places that I like to explore and know more about. Much of my work is in Asia. I have an attraction to Asia, so that's basically where I spend a lot of my time.

As a young photographer, you moved to India to work as a freelance photographer. It seems that this experience had a tremendous impact on your worldview and your work. How did you first trip to India influence you?

Coming from America, or anywhere else for that matter, you immediately see that India is its own unique culture. It's a place that is unlike any other place in the world—you really feel you're somewhere else. And when you're in any foreign country everything is new and you want to look at it and respond to it, whether you write about it or photograph it or just talk about it. Then India is Hindi, it has Muslims and Christians and Buddhists and Sikhs and so on, so it's a really rich mix of different cultures and religions and ethnicities and disparities among rich and poor and high caste and low castes. It's just a really complex place. I return there once or twice a year, depending on the year.

How do you choose the places that you travel to?

It's intuitive. Often it's places that I've been to before but I want to go back to and continue to work. I go to places that interest me—that's pretty much it. I go to Burma every year because I like the culture, the people, and the Buddhist vibe there.

You also frequently travel to Africa, as we can see from your photograph of a child adorned with flowers. Can you talk a little about that picture?

That's in Ethiopia, in a place called the Omo Valley where there's a lot of self-adornment—they like to decorate themselves and put flowers in their hair and paint themselves. It's one of the common cultural traits from that part of Ethiopia, and it's all stuff they find, like flowers, twigs, mud, and clay. It's done for fun, I guess, in the same way we would put on makeup or wear a hat.

What about the photograph of the man with bells? Where did you take that photograph?

That was taken in a place called Assam in India, where there is a very famous temple. In Hinduism, bells are very common, and in this particular shrine there are a lot of bells. The man seen here is a holy man, a Sadhu.

How do people in the places you visit react to your presence as a photojournalist? You once said that "people, when you first encounter them, try and put on a particular mask." Is that something you find around the globe?

Well, they're okay—I'm just a foreigner with a camera, that's how they view me. But, yes, I think most people smile or have some sort of expression when you greet them—unless it's a subway attendant in New York City who never smiles. It's a universal trait, something that we all do when we meet somebody. What I think is more interesting are people that are more natural and relaxed and not trying to look this way or that way but just being themselves. Often people are self-conscious about being photographed and they want to look a certain way, but I think it's more interesting to just have them be natural.

Let's talk about your photograph of rooftops in Rajasthan, a region in India. What is happening in that picture? Why is it so blue? What is that town?

That's Jodhpur, and it's a town where the old quarter is primarily painted blue. It's a famous place because a significant part of the town is painted that same color for reasons that nobody quite knows.

Then your picture Stepwell and Birdsis a very precisely composed image with an uncanny degree of symmetry—even the birds flying out of the well balance each other in the composition. What is this place?

That's in Rajasthan as well. They had an ancient method of fetching water where they'd have these step wells and you would go down and collect your water. I guess this was before tube wells, so they're kind of obsolete now, but they were really quite beautiful in their geometry.

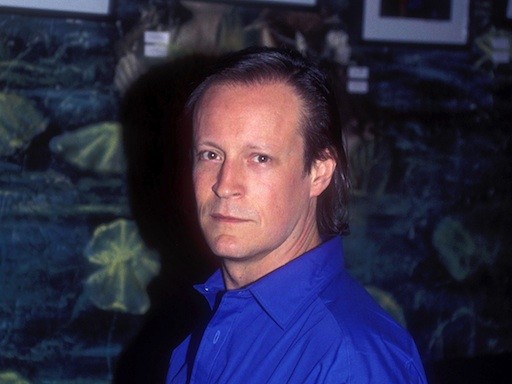

Your photograph of Grand Central Station, meanwhile, brings the focus closer to home. Can you talk about that picture?

That was part of my "Last Roll of Kodachrome" project, where I photographed iconic people and places around the world. When I was in New York I immediately thought of Robert DeNiro, but when I was thinking of architecture I tried to decide what in New York would be considered an icon. There's the Statue of Liberty, of course, but for architecture the best example would be Grand Central Station. So that's what I did.

How would you say your work has changed over the course of your career?

Oh boy, that's a good question. Hopefully it's improved [laughs]. It's hard to articulate.I think in time you understand your craft better and you become more perceptive—you understand light and elements that make pictures better. Maybe you just understand life better. Hopefully you make better pictures as you get more perceptive of the world around you.

What do you hope people get out of your photographs?

I think that in photography, as in writing or painting, there's an attempt to make some comment, some statement—to communicate something about your time on this planet. I think photography is a pleasure. One photographs or writes because it gives you a certain pleasure. It's satisfying to see things and observe things and then share that.

That's interesting because the idea of pleasure goes back to the idea of beauty in your photographs, since their symphonic composition and colors are very pleasurable to look at.

Well, as I said, there's a meditative aspect to it. For me, anyway, when I'm walking around photographing, I get into a particular zone or mindset where I think I become much more attuned to the world around me. It's a joy to be alive, and maybe that's what comes through.

In DepthSteve McCurry on His "Meditative" Photography