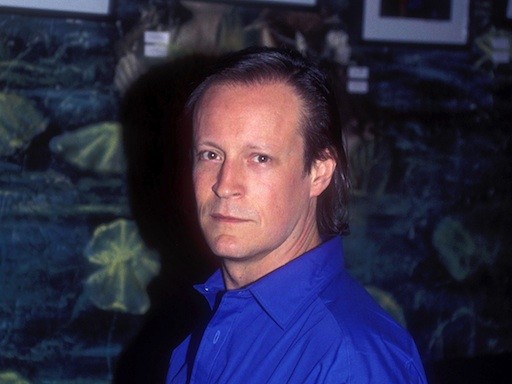

In the world of New York nightlife, everyone knows the name Patrick McMullan. A gregarious, friendly presence at nearly every party of note for the past three decades, he is the one taking pictures of everyone who looks interesting, corralling the famous and the unknown alike into compositions that capture the city's glittering high life as comprehensively as Weegee captured its ugly underbelly. Today his website patrickmcmullan.com receives as many as a million clicks every day from people with the burning question, "What happened last night?" McMullan is the preeminent chronicler of New York's media-saturated society—and, as such, it's only fitting that he got his start from that other celebrity—besotted shutterbug, Andy Warhol. We spoke to the photographer about what he learned from Andy, how he rose to fame in the face of extreme personal hardship, and what, exactly, makes a great party photograph.

For three decades you've been the most prominent party photographer in New York, if not the world. How did you get your start?

In life there are a lot of starts and stops, you know? One thing I would have to say is that I come from a large extended family and we always had family parties and that sort of thing, so I was around groups of people a lot, which helped. My parents used to have parties in the house at night and sometimes I would wake up and grab our little camera and take pictures, and somebody would say, "What are you doing up?" So I guess I was sort of born in a social situation like that. Also I always loved the flash. There's something great about a flash. In the movies it seemed to have a kind of a momentary effect, almost like a slight hypnotism. The flash goes off and freezes things. Also, when I was seven or eight my father got the Polaroid camera when it came out and we used to run around and just take pictures and stuff, and we really enjoyed doing that. And it was great being able to see immediately the results, because most times when you took pictures you took them and nebulously later they'd come back and you could see them. For a younger person, I think, that lag was kind of abstract. I think that really influenced me a lot.

What kind of photography did you like to look at when you were growing up?

My mother always had magazines around the house, so I looked them. She would have raggy, Hollywood-type things like Photoplay, and LIFE magazine was always around. So that influenced me as well. I always loved photography—I always found it interesting. When I was just out of high school, I had a job at the public library in my town, Huntington. There was a lot of downtime, and I found myself gravitating to the photography books and I saw some of the great masters like Stieglitz and Steichen and Robert Frank. I always found the images interesting. Sometimes people, too. I found myself staring at people, being very interested in them. I remember there was that line, "Why don't you take a picture? It'll last longer." Well I honestly think that on some level that affected me because I think, in fact, the great thing about photography is that you're able to stare and examine and look at people in photographs. You're allowed to look into somebody or look at somebody for a longer period of time. I don't know, maybe in there world there are a certain amount of people who are narcissistic—I mean, I guess that word is thrown around a lot—meaning that they're not as concerned with anything outside of themselves, but I believe that I've always been more interested in things outside of myself than myself. I would find myself staring at people and wondering about them a lot. I'm oddly introverted, which is very strange, and as a child I tended to be even more introverted, so I was pushed to become more social, more out there. I kind of learned how to be social in a pragmatic way.

How did you start getting into New York City's nightlife?

I was definitely a people collector, and when I first moved to the city I got in with certain friends. One crucial person for me was a roommate named Ian Falconer [now a famous illustrator and New Yorker cartoonist] who I lived with in college—and I still live in the same apartment I had in college, which is really funny. But Ian knew a lot of people, and he was a Studio 54 person. Everyone wanted to go to Studio 54. I did a lot of that and through Ian I met Andy Warhol and the printer Rupert Smith, who did all of Andy's printmaking. Everybody went out every night, you know? We also went to a Village bar called the Ninth Circle which was a little bit more downtown-y, and I guess I learned to socialize and drink and stuff, too. I was moving along pretty well. I was at NYU studying marketing and business at the business school there. Ian was at an art school—he was taking art history—so he taught me a lot of seminal things. He just had the best taste of anybody I know, and he helped me develop good taste.

You were encouraged early on by Warhol, who once said, "If you don't know Patrick McMullan you ought to get out more." What was your relationship like?

Andy was always encouraging. When I would go to the Factory I had a big camera, and he said, "You really need to have a pocket camera, because they make such good pocket cameras now and they don't really like you to go to Studio 54 and take pictures unless you're really big." So Andy had an Olympus XA camera, and he got my friend John Reinhold to buy me one. It was the most exciting thing to get this camera because it was $200 and my share of my rent was $120 a month and I didn't make a lot of money. This was before I even graduated college. So that definitely affected me, taking pictures socially, because I had that pocket camera.

How did you get into doing photography professionally?

I graduated from college in 1980, but while I was in school I had a wonderful job working for a photographer named Terry Stevenson. Terry was very sociable and he always got Women's Wear Daily and was very interested in society and all that. He was a professional photographer and did a lot of portraiture and product photography, and he had a studio. One of the great things working for Terry when I was in college is that he'd say "take whatever film you want. You can have whatever film you want." And Terry also made me learn how to develop film—he said, "Come on, you've got to learn how to do this." So I was able to develop my own film, and of course I always shot in black and white, because in those days that was all you could develop—color film was more difficult to develop. So I learned to work in a darkroom, I learned to make my own prints, and I learned how to make contact sheets, which was the most important thing.

How did you go from working with Stevenson to working with celebrities?

Terry always said to me that I really loved people. He said, "I hate people, but you love them." He was very funny, and I think that I had a good sense of humor, so we all got along. But he always thought I'd be best at a public relations firm working with movie stars—I was kind of starstruck—and he always pushed me to work with his friend Michael Maslansky, who was one of the founders of the big PR firm PMK. In fact, when I graduated college I got a job working at PMK, which I absolutely loved. Part of my job was going through newspapers and magazines and just in general knowing who the clients were. I learned how important press was, and I got to meet a number of different columnists and be in that world of what you would call A-list parties, which I liked. I really liked parties in general, and the way people behaved at a party—everyone was in a good mood and the conversations were lively and visually it was great fun. I did get the job at PMK, and I worked there for about three months until I was diagnosed with cancer. I had a bad form of testicular cancer called Embryonal Cell Carcinoma, and it had spread. At the time I was about 22 or 23. So that had a big effect on me.

I can only imagine.

I can't explain how intense that was. I had chemotherapy for a year and a series of three different operations to remove tumors. It was really quite hellish, and in those days the chemotherapy was ten times stronger than it is now, so it was really, really something. But what I didn't realize was that at that very time, in 1981, it was right when so-called "gay cancer," as AIDS was called, was just starting. So people that saw me ill didn't know what I had or what was wrong with me, so people were very afraid of me and my illness and it was a tough time. Andy was terrified of illness. I didn't even know, but I got a little bit of a cold shoulder from him. Ian, of course, stayed very friendly and close, but he had moved out to California—he was sort of a muse of David Hockney. But at the end of my treatments, I wanted to get my job back with Michael Maslansky at PMK more than anything. I thought that was really what I was going to do. I remember Ian said, "Well look, come out to California. You're crazy to be in New York. You should be in California where it's warm and sunny. I'm in this big, beautiful house in Hollywood Hills." David was in New York at that time, working on the sets for an opera, and Ian asked David and David said, "Sure, let him stay in my room." So I actually stayed in David Hockney's room for something like two months.

While you were kind of convalescing?

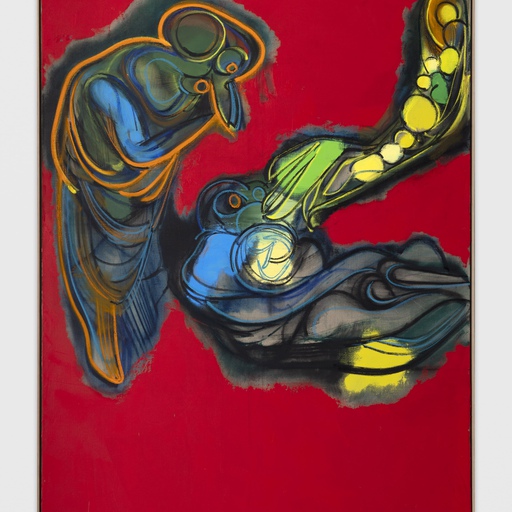

Yeah, well my chemo was over, and I was very depressed, and in the back of my head I thought that if I went out to California I could meet with Maslansky and get my job back at PMK. That was kind of my goal, to get better and have a little fun again. You've got to remember I was only about 23 at this point but I looked so old from the chemo, with no hair and being so skinny and all that. Suddenly my hair started to grow and people that I was now seeing in California didn't see me as being ravaged by cancer, so that kind of gave me a little shot in the arm. I met with Maslansky finally, and he said, "No, I don't think we're going to be able to hire you back." I didn't realize but movie people did not necessarily want to have someone who had cancer around them. Now I can see why it wouldn't work. The thing that was important is that while I was at David's house, he had big red-covered volumes of books full of snapshots of his friends and celebrities that went all the way from 1960 to 1968, with people like Mick and Bianca Jagger and Christopher Isherwood and Andy. They really were really interesting, and what I realized I could do, that I had been doing anyway, was make a diary of my life. I really did not think I was going to live very long. I did not have HIV, I had a cancer that had a fairly good cure rate, but it wasn't nearly as high as it is now. Nevertheless I decided that if I wasn't going to be able to get a real job then at least I could go back to work for Terry Stevenson. So I did that, and when I got back to New York I was pretty much more refreshed and feeling a bit better.

Is this when you started taking party pictures for magazines?

My friend Danny Fields, who was a big music-industry manager and managed the Ramones, had a party at his house and he introduced me to Annie Flanders. Annie had been the fashion editor for The SoHo News, and I had had my first photo credit in The SoHo News as "Patrick," I didn't even have a last name. Anyway, Annie met me and at that time she needed a photographer at Details who could run around with [founding Details editor] Stephen Saban and do all the nightlife pictures. Wow, that sounded great, because while I was sick I couldn't go to Studio or the Mudd Club or any of the places I use to go, and this sounded like a lot of fun. Anyway, I did get that job and that was to be my life then, well, for the rest of my life. I really started to take pictures regularly and I could develop them myself, and it was a monthly thing. I had also fallen into staying up really late and sleeping really late, and much of the world did not work that way, but at Details they worked that way. So at 3 o'clock in the morning they were at the office and at noon they were asleep. I'd call sheepishly sometimes at 8 o'clock at night and say, "Oh my gosh, I just woke up," and she'd go, "Okay, that's fine. Just come over and make your contact sheets and develop your film and come over." So that's what I'd do, I'd bring maybe 30 contact sheets and her and Stephen and I would go over pictures and ask who people were. It was a lot of nightclub people, like Cookie Mueller, Tina L'Hotsky, and Dianne Brill and people like that, and they would always be very excited about some of the pictures I got, like, "Oh wow, look at that picture, that's great!" So that was always fun for me.

When was it that you first got your own photography column?

Around that very same time, I got another job with a magazine startup that was called 212. I was made director of photography—which meant that I printed all the pictures, because there were photographers but no one knew how to make the prints. So I worked a lot, I made a lot of prints, I took most of the pictures, and then they gave me a column at the back of the magazine with a little picture of myself. They wanted to make me somebody big, they said, because then more people would let us come in to cover parties. I would get a lot of beautiful people of the day and important people—I mean, almost anybody would pose for a nice kid with a pocket camera. And you have to remember: in this environment today there are a lot of people running around with cameras and cell phones, but in those days there were not that many people that had cameras. Also, to make a note, I probably would not have been a photographer like that had it not been for the illness. Because the illness gave me the extra chutzpa—that's the Jewish word for "having balls." So I actually lost a testicle but got balls. But I was still always very self-conscious and afraid to go up to people. My publisher would always say, "Oh god, go! There's Susan Sarandon, go take her picture!" And I was nervous, so I always asked people for permission. I didn't like the idea of just snapping someone without them knowing—it seemed rude to me, and I was brought up with very good manners. And again, I went to parties—I didn't do "step and repeat," which is what they have a lot of press photographers do now, where for a big event you'd line up where the people arrive and take everyone's picture. I never cared for that kind of work, because I found a lot of the photographers to be a little bit coarse. And because of the fact that I had almost died, I wasn't in it to make money. I was in it because I liked to go to parties and I liked the scene and I liked to see the movie and I liked to go sit at the dinner. I was friendly and warm and a good guest. To me, the key to being a good party photographer is to always be a good guest first. Always.

If you were nervous about approaching celebrities, how did you manage to do it night after night to get your pictures?

I was never fearless, but I wasn't shy. I would have to put it on, though. I would have to act as if. I always wanted to be an actor, and I was very good as an actor in college. I took some acting courses and they said I was a natural and all that, but I did not have the narcissism, and I think that's important. Narcissism has a negative connotation, but you have to really believe in yourself and have a hard core to go to all those auditions and dazzle people just to be an actor. But I was able to act a certain way when I went up to important people, and while I was reluctant I knew that I had to do it or somebody else would get the job. But I found that 90 percent of the people I would meet were fairly pleasant and that would empower me to not be afraid the next time.

How did you choose who you would photograph for your column?

One of the things that I've always been, more than being celebrity-driven, is people-driven. I would see a person and I'd be curious about them so I'd go up to them and say, "Can I take your picture?" So it was more about individuals who were not necessarily famous so much as interesting or attractive or a friend of someone. If I was with Stephen and I would meet somebody, it would be a given for me to say, "Oh, let me take your picture."

Just to go back one thing, it seems that Warhol was a big influence because this is exactly what he was doing at the time, going around and taking pictures of people he thought were interesting. Did you two stay in touch?

When Ian was my roommate I got to go to dinner with Andy and talk with Andy more, but as I got more successful at Details magazine he really liked me because I always gave him press. I always took his picture and put it in things, so he thought I was pretty cool. He liked me a lot. We both had a love of photography, so we talked photo. We also had a great love of television, and towards the end of his life we talked a lot about television and starting a channel. He was considering buying a channel. I remember him saying, "$100,000, that's a lot of money." I mean, it was like a million dollars today, but it was something he could have done. We did a lot of talking and chatting.

He had that great quote, "If you don't know Patrick McMullan, you ought to get out more."

He said that to [Warhol Diaries co-author] Pat Hackett. I don't think it was in the diaries, but it was one of those things that he said when he talked about me. You have to remember that Warhol was not just Andy, it was all the people around Andy. Andy was like the kingpin, and you could have a friendship with him but it was always a little arm's length.

You've photographed countless celebrities, including some powerful and private people, and they always smile for you. That's not so easy. How do you get them to smile?

The thing I do is that I'm usually very much there with them and usually have a little bit of a chat. I'm not snapping pictures without them knowing, so most people smile in the pictures. A majority of people just do that naturally. In those days I would take one, two, or three pictures of a person because I didn't have a big camera, I had that small thing, so I wanted to make them count. It was more of a quick portrait idea. So I was engaged with people and I tried to be fun, sweet, and funny.

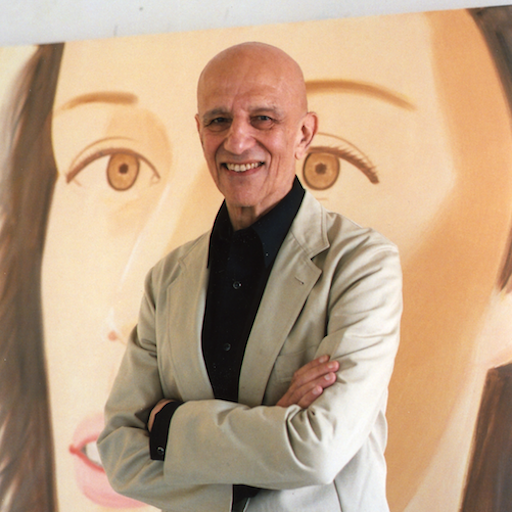

In 2007, the art dealer Gavin Brown curated a show of your photography at his onetime bar Passerby called "Who Am I?" In the show's statement, he wrote, "In this little village called New York Patrick McMullan is there to confirm that last night did actually happen. That we do actually exist." What did you make of that show?

Gavin found himself looking at my website, because in the it used to be that if you couldn't go to a party or something someone would say, "Oh, go to Patrick McMullan's page," and you could see who was there. He also became fascinated by the fact that when I didn't know someone's name I put a question mark next to the picture that said "Who Am I?" I did that because I thought it was funny, and it's the quintessential question anyway: "Who is somebody?" And if you saw a question mark saying you could click on it and fill in the name. So it engaged people. They may say, "Well, I don't want to end up a 'Who Am I?'" So Gavin says "I really want to do a show where I do a stream of consciousness on your website and just pick all the "Who Am I?"s. So he picked 6,000 pictures that I had taken on my site and we made 5x7 pictures and he and his team hung it all up and it was just this really cool thing. Then he put the 5,000 pictures on a disc and he said, "We're going to sell that disc for $100,000." I said, "$100,000? What are you crazy?" And he said, "I am crazy, of course. I'm doing the show, aren't I?" And he said, "I'll donate one to the Smithsonian." So I guess one of them has been donated to the Smithsonian, and I don't think anyone ever bought the other disc. I guess Gavin still has it.

What do you make of the art world, the gallery world?

Gavin is great, and I love him. He's a very interesting and cool guy, and he knows how to play the art game. I don't play the art game other than I go to places. I'm really nice but I've never been a very good sycophant and the art world sort of demands that. You have to make best friends with curators, you have to make best friends with rich people, you have to do a lot of that kind of stuff. I don't know how to put it. I'm really genuine and warm and friendly and like the people that I like, and I can be nice to everybody, and I want to be nice to everybody, but I'm not really someone who would call you to do this interview—you gotta call me. I wake up, I do what I have to do. If I have a date free I just sort of go walking around and take pictures, just randomly. That's what I do. I'm a lot like Andy too, because I like to go to junk shops and art galleries and antique shows. I like looking at stuff and collecting stuff.

I wonder, how you see your work functioning as art? Is it that some of the photographs qualify as art, or something else? How do you put yourself in that category?

I remember Andy said something that I always loved and laughed at because I knew what he meant. He said that, "Art is what you can get away with." If somebody thinks it's art, if they like the way it looks and want to hang it on their wall, then I guess it's art. That's what I think of art: if somebody wants to look at it more than just once, when its happening, then it's art. I mean it's all semantics. I don't think of myself as an artist, I think of myself as obsessed with doing what I do. When I'm not working, I still take pictures all the time. I take pictures of the television, I take pictures when I'm walking home at night. I never stop, I just keep going.

What is the key to a great photograph?

I think what makes a great picture is when you do a double take. When you look at it and you have to look at it again. Sometimes something funny happens in a picture, or people make a funny face, or you get something with colors or shapes. I love taking abstract pictures of real things, where people say, "What is that?" And I go, "I'm not telling." But I always wind up telling. You asked me about people that have influenced me and have inspired me, and I have to mention so many different ones. I loved Alfred Eisenstaedt, and his original picture of the sailor and the nurse kissing [in Times Square on V-J Day]. I remember seeing that in the 15th anniversary issue of LIFE, and I can remember staring at that picture and trying to understand it. It not only made me do a double-take, it has resonated with me always. It's a brilliant, brilliant photograph that literally encapsulated a feeling of the times.

The rich and famous clearly trust you, in part because you don't take—or at least you don't publish—embarrassing pictures. Other famous photographers who have captured the rich and famous on the town, like Weegee for instance, have taken another approach, often taking pictures that expose or lampoon their subjects. What are the virtues of one approach versus the other?

Let me explain. First of all, there are two different things in photography. One, there's somebody who sets up and has in their heads what they want. Then two, the real photographer, to me, is someone who wants to capture a candid moment. Every photographer who ever existed wanted to capture a candid moment. That is the great joy. That is what keeps people coming back to photography, the chance to capture something that resonates, that encapsulates. That is the great excitement and joy of photography. And probably art, too, is just getting that little something special. So a picture like Eisenstaedt's is probably, to me, the greatest of all the pictures that have ever happened. I mean there are many, many, many, many like it, but it encapsulates the quintessential idea of photojournalism, art, society, beauty, emotion. It really says everything and it's happy and upbeat. I also, because of my personal illness and demons—because I battled depression, too—I'm looking to show upbeat. I have a lot of downbeat things, too, but I like to show upbeat. It's my way of raising the bar, raising the level-making life a little better. So, to me, if I can lift spirits on any level then that's my intention, after what I've personally gone through. I want to see beauty and aesthetics. To me that's what I prefer, do you understand?

Of course

And I love Weegee. Not all his moments are dark and morose. He captured real moments of the people he was around, just like I capture real moments of the people I'm around. This is New York. Uptown, downtown, social, nightclub, art people—I mean, I do it all. What you see of mine is a job and work. I have to make a living. Mother has not left me a trust fund, so I have to work and support my dependents and the people who work for me and need their job. I like to do jobs that can make me money, if I can. Andy also taught me that. He said, "You gotta bring home the bacon. You've got to because if you don't, no one else is going to do it." I remember when I had cancer, at the very same time, my father was out of work and it was a tough time and there was no money. We had no money. So I always worked.

Who is the most photogenic person you've ever photographed? Someone who you can take a hundred pictures of, and a hundred pictures come out well?

I would have to say Kate Moss and Linda Evangelista are great subjects. Models are great because a good model looks different all the time, yet they look like themselves. So those people are great. There are so many people who are really good subjects, and there aren't that many who are horrible. You know, some people still think that they're 17, that they had one good picture of themselves and every picture since then has been a disappointment. So I always try to explain to people, look, if you don't think you're photogenic, ask the photographer to take more pictures. Because he'll pick the best one! The only way to get a good picture is to take a lot of them.

What is the trick to posing for a great party picture?

The majority of people, when they look at a picture of anybody they go, "Oh, if you're smiling, you're happy." They think there's so-and-so, and he looks happy, he looks good. If you're frowning or making a weird face or are cowering, then you show yourself to be cowering. So why not, when you see a photographer, say, "Take more! take more! take more!"? And you have to act as if. In this world that we live in, we all have to act as if when we're in those situations. Do you think these people that went to Vietnam knew how to shoot and kill? No, they had to act as if. When somebody steps in a war, do you think they know how to do that? No, they have to act. One has to be what they are trying to be. Like I'm a really nice person, people tell me. But that doesn't come naturally, I have to make an effort to be nice. In high school I was voted "Most Friendly" because that's when I learned how to become friendly.

Your website gets up to a million hits a day, and you run a huge industry now. You're in New York magazine every week and you have columns. How many people do you have working on your photography team?

Oh, a lot. I don't know. I only know in December when I write everybody a bonus check. I think I wrote fifty bonus checks, but I don't remember exactly. I have about five or six people in Los Angeles who work for me there and then I have people here in New York. And again, a lot of people are freelance people. Most of them are not staff people. When I need them, I call them. Almost every single person that works for the Patrick McMullan Company is a photographer of some sort.

What is the essence of a Patrick McMullan photograph? What is your calling card?

I take so many, it's hard. It's like what is the essence of a chocolate chip cookie, you know? But what I would say the main essence of an everyday picture is that people are looking well, there's no games being played. It's an honest rendition of who a person is at that moment, the way they're dressed, and who they're with. As far as my personal work or things that I do outside of my business—and there's always been art and commerce in every kind of a business—it would have to have that sense making you say, "I'll look at it again and again." That's the kind of photograph that I would sign.

You once said that you thought you could be a better photographer if you weren't so consumed by running your business. if you were to step away from your empire, what kind of pictures would you take?

I would love to just take a lot of pictures without having to say too much about them to people. I like taking pictures of people that appeal to me. I like cute. But I also like walking around and taking pictures. I can't get enough. When I'm home, if I turn the television on or I look around my apartment, I end up taking pictures of stuff. But you have to understand, I'm constantly looking at other people's work, not for inspiration but because I'm a collector. I'm a collector of hundreds of thousands of images. I love looking at imagery.

So you're a born photographer.

I don't have enough balls to stop doing what I do. I'd be afraid for all the people that are dependent on me. What would they all do if I didn't make money? I haven't even paid myself a salary in so long because everybody else needs the money more. Because I have a business, my cabs are paid for and my meals. Every once in a while I buy really good things. If I have money, I buy photographs. Most of the time I just buy things at junk shops that are a dollar or five dollars or a hundred dollars.

You know, Patrick, it's such a pleasure to hear your story.

When Apple did their campaign in SoHo in way back they said "Think Different." I always thought different. I like to I have good ideas, and I always think that I'm well intentioned. I want everybody to look their best and feel their best. I want to raise the bar, not lower it. That's very important to me, and I think that comes from my illness. I want to try to keep things upbeat. But I love beauty. I've got to tell you, I'm a real sucker for beauty.

In DepthPhotographer Patrick McMullan on Being a "Real Sucker for Beauty"