The South Side of Chicago, historically black since the Great Migration sent tens of thousands of people fleeing the former Confederacy to settle there, has long been the Windy City’s neglected stepchild—filled with vacant lots and tumbledown housing, hindered by discriminatory real-estate practices, and physically separated from the more affluent white neighborhoods by two highways. So it was something of an anomalous event, to say the least, when last weekend a glittering, international art crowd—deep-pocketed patrons, major museum directors, famed architects, powerful curators, and top dealers from both coasts and Europe—convened on 68th Street and South Stony Island Avenue to celebrate the unveiling of a major new arts center. Even stranger? The man behind the building was an artist: the 42-year-old potter, singer, urban reclaimer, and son of a Chicago roofer, Theaster Gates.

The $4.5 million Stony Island Arts Bank, set to open to the public on October 3rd to mark the vernissage of the city’s architectural biennial, is the most ambitious expression yet of Gates’s unusual approach to art. A 17,000-square-foot Neoclassical building that previously housed a savings bank, it now contains meeting spaces, classrooms, a majestic library holding the archives of Jet and Ebony magazine (entrusted by the Johnson Publishing Company), a collection of racist American “negrobilia,” and the trove of records left behind by late Chicago house-music legend DJ Frankie Knuckles. The undertaking is the apogee, so far, of a civic-minded effort that Gates—who trained as a city planner and once worked for the Chicago Transit Authority as a public-art commissioner—began nearby with his celebrated Dorchester Projects, a series of defunct houses he transformed into a makeshift art laboratory and studio complex.

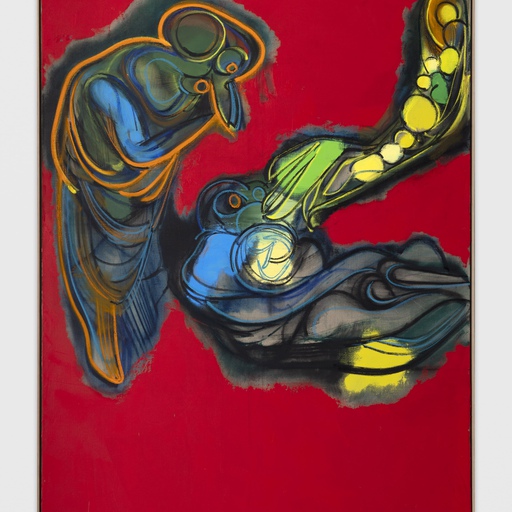

Reworking the urban fabric, it should be said, is not the whole of what Gates does. His sculptural work is fervently collected by people and institutions the world over, and his installations currently hold court in the Venice and Istanbul biennials. But, to a large extent, that art serves as fertilizer—and the money it commands, nitrates—for his larger project of growing communities out of the cracked sidewalks of disenfranchised neighborhoods. He calls these spheres “black space.”

Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Gates—who has a major new monograph out this fall from Phaidon—about the ideas behind his various social and sculptural endeavors and what his mix of art, architecture, and urban planning is really all about.

To begin, tell me a little about the Stony Island State Savings Bank. Where did this project come from?

So, the bank is several things. First, it was born from the determination that beautiful architectural forms in poor neighborhoods are still important architectural forms and should be preserved. And then, one of the things that I have been challenged by as an artist over the last several years is that there’s project-making that I feel really committed to—like the sculptural aspect of my practice, which has been growing—and then there’s this other part that is about platform-making: how do you create conceptual platforms that are real, in the real world, in the real communities that can have an impact in the real world? I find it’s this platform-making that allows me the kind of intellectual and creative space that I need, complementary to my studio dirty-space.

Alright, so, the bank is kind of an intellectual hub in the 'hood. You know? It’s a model of having a cultural space that functions as an exhibition venue, an archive and collections venue, and then a space where people can hang. A space on the South Side that’s meant to evoke deep conversation, new friendships, and, ultimately, a community of people who also want to help with the transformation work of what needs to happen in the 'hood. Where other likeminded folk can come and say, “What else can be done? What else would I love to do on Stony Island, 10 blocks away from the block where I live? And how can I do that?”

I want to cultivate that, so it’s a place where we can have these conversations and talk candidly about issues of space-creation, of space-retention, of active growth without gentrification, without new communities —how to remake the communities that we have already here stronger. And then, how do we say, “Welcome”—because there is a lot of land, and a lot of vacant buildings—and “be a partner and grow with us.”

Who is the audience you’re trying to reach with the center? Is it a community of like-minded activists?

No. In the same way as my practice, it’s the people who live down the street who like watching Saturday morning cartoons but who also want to see really hard-to-find independent black films—they can see this through the Black Cinema House at the bank. Then, for kids who are studying art, or who are in elementary and middle school in the neighborhood, we’ll have programing for them too. We’ll have research, reading, and poetry events that are made for young adults and adults who are interested in investing time researching our archives: the Johnson Publishing Library, our archive of black memorabilia, the Frankie Knuckles music collection that we have. The way it is in my head, all these things we have are really just the raw material that allows educational programming, youth programming, and art programming to happen.

It’s fascinating that you have such multivalent strands of black identity and black history represented in the center, from the self-reliant uplift and inspiration of the Johnson archive to the baggage of the so-called “negrobilia” collection to the underground-heroism of the Frankie Knuckles repository.

Yeah, that’s exactly right. The American black memorabilia is the stuff that in some ways inspired John Johnson to build his publishing company, because he wanted to see new images of black people, and he wanted black people to affirm themselves. We want to emphasize how important the creation of that platform was.

The whole composite amounts to a kind of thinking mind that is dealing with multiple histories of what it means to be black in America. When people walk into the building and encounter these documents, what do you want them to walk away with?

Above all, I want them to come out believing that people who live a neighborhood can be proactive and care for the spaces that are in our neighborhoods. I also want them to leave invigorated and charged, knowing that there’s a safe place for the history of black people.

In your work, it’s often the case that individual elements can only be fully understood as pieces in a larger game where the goal is not an aesthetic one. Your sculptures, for instance, are very interesting to look at, but an equally important component is the fact that the proceeds from their sale underwrite your larger social project. How have these aesthetic and social elements evolved in your work, and in the way you think about what you do? Have they always operated in tandem?

Well, the aesthetic and the ascetic have always been big parts of my life, and kind of foundational to the black experience. Black people have style, and they have known god. You know? Those things are the bulwark of the black experience, and I’ve spent my life mining them—whether it be in scripture, or music-making, or my histories with performance—but I also feel like those things were already cultivated in me. And I feel a lot of my time right now is just being spent considering what are the best ways to share these ideas, and sometimes a sculptural work is the best way to showcase what is on my mind, and sometimes it’s a lecture, or a sermon, or a song, or fashion.

This is a moment in art when one doesn’t have to feel restricted in the form one chooses, and I feel really comfortable leveraging these forms, thinking, “What are the things that I want to say?” and then finding the right medium to showcase it. Sometimes the right medium is an abandoned building, or something like that. I don’t believe that city policy is the answer to everything, but I also don’t think that art can solve all problems. Art shouldn’t be made to solve all problems, either, and there are times where I have to take off my art hat and just be a citizen and know how to get shit done.

You’ve said that 90 percent of the time you spend in the studio is devoted to your building projects and planning initiatives, and that 10 percent is devoted to art. This is a bit of a discordant concept, since these days we’ve come to understand that anything an artist does is wrapped in the larger context of their “artistic practice” and therefore becomes art. In your mind, are your buildings art? Or are they something different?

You know, I think that the buildings are buildings, but they come out of an artful life. They live differently in the world because they were done and considered by an artist. I don’t think everything needs to have the word “art” with a big ‘A’ on it. But I also think that artists have the capacity to make works like policy and community development, or finance for development. I think that we have the ability to make those works bigger and more expansive. So, really, it’s almost like: artists make good things better.

What kind of systems do artists bring to an existing superstructure that then allow us to hack them and interrupt them and make them work toward whatever our causes? A lot of my work is looking at that. So, in my studio there are seasons, and there are seasons when I am 100 percent thinking about art and then there are seasons when I am thinking about this gala that's coming up. And I feel like I come into those different seasons with the same brain all the time.

One of the great things about art that you don’t always get in other socially active fields like urban planning is that there’s a lot of money that’s excitedly at play, and a lot of ready media attention as well. You can probably get more attention to a project that an international artist is doing with a run-down building on the South Side than you would for a well-meaning social project coming out of the existing civic infrastructure. With this in mind, it’s notable that the site you chose to remake is a bank—that you’ve transformed it from a savings bank to an arts bank. So I wonder, what are the layers of metaphor and symbolism here?

I would like to imagine that, most of the time, most of my work is operating in the real. There’s a part that is… well, I would like to say the symbolism that you are seeing is pragmatism. But there’s another part of me that feels very much like the work can accomplish several things, like with the bank. The bank needs to operate like a cultural space, and it also needs to demonstrate that the South Side is worth investing in. It also needs to show what an alternative cultural space is supposed to look like, so it can help my friends in Detroit, or my friends in Saint Louis, do the amazing things that they want to do.

So I have put a lot of pressure on whatever this thing is to perform multiple codes, and one of those codes is symbolic. It’s just like making a shoeshine stand. The shoeshine stand is going to mean ‘X,’ and for some people that x might be “This is a horrible history that I do not want to think out about, and I don’t want to have that shine on my shoes.” For other people, it might be nostalgia, like, “Oh, I remember when grandfather used to shine his shoes before he went to church.” Then some people will say, “Oh, that’s a really interesting thing, who did that?” It’s a kind of conjuring that draws on the symbolic meanings of that object, and having these multiple reads on that thing is exciting.

When I get bored, on the other hand, it’s with singular tropes, where the things are such and such a given and the artist doesn’t want it to be mistaken or misread. Sometimes, again, that’s for economic reasons or power reasons. But I like the slipperiness of an object, what an image means to me, or what a project means for me. I think that slipperiness is where good art lives for me. That people don’t actually have to know that the bank stands for this kind of economic agenda or if it’s just from a love for the land. People automatically assume that I grew up in the neighborhood on the South Side because I’m doing this work here, and it’s not true. This isn’t my neighborhood, but why should someone have to live in a place in order to do good things in a place? Is that the only reason that people would invest deeply into a place, even if there might not be a return?

I think that I am always trying to figure out other stakes for me personally that may be slippery for others, that may not make sense for other people. But they’re the quiet justifications that make me feel like the work that I’m doing is really important to me.

To raise funding for this project, you went to Art Basel in 2013 with 100 “bank bonds” that you etched into marble slabs taken from the building, inscribing them with “In Art We Trust” and selling them for $5,000 apiece. Currency is just a mass-produced token with some art and a number printed on it to begin with, and here you essentially minted your own money at an art fair and then funneled that money into creating this social space. This approach is part and parcel of your overall project, in which you convert parts of buildings into art, exchange that art for money, and then put a lot of that money back into the urban infrastructure. Can you talk a bit about this process?

Let's try to pull it apart. The thing that I’m most excited about with the bank and the bank-bond project is that it gave me the opportunity to be literal about economies. The Stony Island Savings Bank was this failed bank that was built like banks could never fail. In 2008 we had a housing bubble burst after a conservative community had been blowing it up for years and years, and, in the end, we needed the government to bail them out to the tune of three times the money spent on welfare in the last year.

We ended up justifying these white executives—powerful men and women who mismanaged private funds—who were not committed to black lives but only to owning land in black space. When they lost their stuff, they got the great bailout; at the same time, as a result, all these buildings in poor black neighborhoods were available. So it was in these conditions that I found myself with a failed bank, and here I was being invited to Basel, the land where banking never failed. So what did I do? I asked bankers to help me save my bank. That felt poetic.

So when people say, “Why don’t you use the bank bonds for everything you do?” well, the answer is that then it would just be a fiscal tool, and that’s not what I was using it for. I was using it for poetry—that pieces of marble from the walls of the bank, from the counters of the bank, from the shitters in the bank should become the currency that the bank uses to pay for itself, and that it should be bankers who revive the bank.

That little possibility was super-interesting to me, and so in some way I needed the participants to really understand that, as collectors, they are consciously acquiring things that increase in value—and that it’s unreasonable to think that only collectors should have the luxury to be conscious of that, and that if an artist ever became conscious of the economics associated with the art world then they would no longer be pure. That’s bullshit.

Do you think that other artists should take your lead and engage in this kind of reallocation of capital?

In my case, I just needed a way, through poetry, to get the art world to really reflect on what it means for these resources to fall where they do. Now that the building is built, I don’t think that all artists need to be engaged in building projects, or that they should use resources in the same way that I use resources. But I do think that there’s a way in which we can ask the resources in this world to do more, whether that means people, and people’s money, or whether it’s the federal government or the state.

I think if we apply creative responses to policy and to the landscape of the city, we can all be artists in the terms of the urban forms and the policies that shape our cities. I think we can get more from the city—that we can find greater solutions for education and healthcare and culture and the distribution of resources. And all of those things seem like reasonable fodder for my artistic practice.

You mentioned “black space,” which is a concept of yours that you’ve invoked on previous occasions. I know you’re also interested in Henri Lefebvre’s idea of the “production of space,” which is a Marxist interpretation of the way communal spaces are formed and express their place within a socioeconomic hierarchy. As someone who has trained as an urban planner, what is your vision for the South Side that you hope to cultivate through the Stony Island Arts Bank?

If we look at my personal history alongside my economic and cultural history, I was not born with means, and when I was younger I didn’t have many resources. In some ways, this project is about what’s required for an average person to do seemingly impossible things. That is a kind of question that I am always asking myself, and I think that I’m asking myself that question because I really believe that when people who have tasted that bitterness come into power they either become corrupt or amazingly adept at making great things happen. And I have the privilege of empathy.

So, it’s like, all right, now that you have access and you have these big ideas, what do you do with that? What are these responsibilities that I feel personally—not as an artist, because I don’t think artists have the burden of a way of being, but as a human? And as much as I have certain days of losing myself in the abyss of art-production, even if I could live my whole life that way I probably wouldn’t want to. There’s another kind of ideal that makes me want to do other things in the world because they seem to matter—not because I have to but just because they matter to me. And so I grapple with those things.

With black space, what I am trying to do now is ask, “If the government isn’t going to care deeply about the education, the healthcare, and the cultural need of young people or the poor, then what are the ways in which we can make those things start to happen?” I think that everyday people are going to have to care more about more things that we expect the bigger institutions to care about, things outside of ourselves. We all pay taxes, we all belong to a kind of commonwealth, there is a democracy here. But, while I am not a bootstrap guy, I really think that if the kids on my block are not getting their homework done and there’s nobody helping them through tutoring, then maybe I have to make a couple hours available for that and be a mentor for some of those people.

And when I say “black space,” by way of explanation, it’s not about all black people all the time, but it’s about what happens where there is a unity of vision and a singular awareness of a set of things and then there is a platform where people can make those things happen. For me, that’s really what art is. It is the ability to look at the world and see a moment, see a gap, and do something with it and make something happen. That’s all I’m doing.

In your monograph, you lament that the ambition in art has diminished since the age of people like Picasso, and that "few people are imagining the great symbolic acts" anymore. What are some of the great symbolic acts that inspire you, and what lessons do you extract from them?

The Carnegie Libraries. The Rosenwald Elementary Schools around the South. Tuberculosis centers. Big buildings with big windows, open spaces, fresh air, and lots of light. Moments where science met architecture. Spiral Jetty. When artists were courageous enough to say there are other moments besides the moments that happen in museums and galleries. Motown—the idea that black people should be responsible for their own music production. The DuSable Museum [of African American History].

What is the DuSable Museum?

An artist named Margaret Burrows in the late 1950s decided that black people should have cultural spaces in Chicago, and she went about engaging the city in creating arts centers on the South Side that are now slowly being rebuilt. She had a vision that said, you know, if our work isn’t going to be shown in larger museums, then we should make space for ourselves. She was an artist who did something beyond art to celebrate other artists. I feel like I am working in this legacy.

You come out of an urban-planning background academically, and artistically you come from a background in pottery, having apprenticed for a year with a master potter in Japan. One could say, perhaps, that pottery is really architecture in its most intimate, indexical form. What are some of the key lessons that you learned from the discipline of pottery?

That groups in focus can do what individuals can’t, and that doing collective work can be an amazing way of working. That there is no need to diminish the cultural specificity one is born with to be celebrated or lauded. Part of what I loved about Japan was how there is such a beautiful recognition of the importance of history that permeates the culture. Even if contemporary culture is trying to break from tradition, there is still a beautiful Japanese-ness about it. I've carried that theory into the work I do on the South Side—that what we call a vacant lot is actually land waiting to be beautiful. And that black space seems to be filled with this kind of land in our city centers. So how can we think differently about that? I think it has to do with a recognition of pride, and a kind of care, and a history of respect and great leadership.

I think about that a lot. That excellence matters, and that if we are going to do things we should try to do them very, very, very well. And that whatever that I am able to do is a kind of humble service, just a small amount of the work that needs to be done. And that I should approach it in that way and keep my head down and just keep working.

You have been scaling up the role of what an artist can be, and now you're wielding significant sums to alter a city's infrastructure in a way far that goes far beyond Gordon Matta-Clark's architectural interventions. Your staff and your operational budget are more in line with a well-funded startup company. Is this a context you are comfortable working with, as an administrator or project manager?

It just sounds like artistic leadership to me. I think what you are giving a title to is really just skill sets. This is what I am trying to share with other artists—that great works of art require administration. That’s part of the deal. And the more that you recognize that it’s part of the work, the greater the works you can make.

The South Side is slowly beginning to show the impact of your architectural projects, and meanwhile you’ve also been applying your aesthetic internationally through all these biennials. Allow me pose to you the classic question investors ask a startup: Is it scalable? Is that something you think about in the terms of the work you’re doing in Chicago?

You know, businesspeople use the word scale because that measurement allows for them to justify a dollar value associated with growth. If you were asking me if my vision is infectious and replicable, if it’s inspiring to others who now want to do similar work, if it renews people’s commitments to their communities? The answers to those questions would be yes. Whether or not it’s exportable is less my interest. But can I share my great ideas with other people and have big things happen? I hope so, and I think we are doing it.

It’s been great to work with the mayor of Gary and the city of Gary to start to talk about the transformation work we can do there. It’s great to work with the city of Bristol to imagine how the reactivation of a former sacred site in public space can be a way of platforming amazing voices in that city. So it’s not just about doing this on the South Side—it really isn’t a South Side story at all. It’s about how can we look at a place for what it is today and say it can be more, and then make whatever that more is specific to that place and those people and their willingness and hunger and resources and administration. It’s all of those things together that then allows something amazing to happen.

So I’ve really spent a lot of time thinking about how to make these ideas infectious, but only because over time I’ve gotten these great viral ideas from others. And I don’t feel like I created this viral new thing, I think I’ve embodied a couple of different sets of skills in order to make things happen—and that feels great. I’m excited to share those ideas with others, whether it’s through lectures or mentorship or hiring people or teaching at the University of Chicago, in the hope that more of us can do more good work.

The Stony Island Arts Bank is now completed, and about to open to the public. What’s next?

I’m going to take a couple of days to think about it. I’m really interested in developing more systematic structural ways that I can share these ideas with people, and then I’m excited to get back in my studio and have a season of making for some of the large exhibition projects that I have in the next year or two. I’m super-excited that this Istanbul Biennial has gone well and that Venice went well, and I think it’s a good time to reflect on what the bank can do and what's possible now that it's open.