At their best, great artworks allow us to reevaluate the stuff of daily life. These seven pieces excerpted from Phaidon’s new book Body of Art all take on that part of our lives most of us love to hate: work. Depicting everything from the hauling barges and the scraping of floors to childcare and the labor of the creative process, these works show people (and one monkey) in the midst of the daily grind.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Art and buy the book .

BARGE HAULERS ON THE VOLGA

Ilya Repin

1870–3

Russia’s greatest realist painter, Ilya Repin (1844–1930), was still a student in St. Petersburg when he began planning his masterpiece, Barge Haulers on the Volga. The impetus for this painting came from seeing teams of men pulling barges on the river Neva. Shocked by a general lack of concern for such human haulage machines, Repin travelled to the Volga, Russia’s main waterway, where he made studies of the local burlakis (barge-haulers) near Stavropol. His cast of characters for this work comprised haulers of varying ages from different backgrounds: Russians, a Greek, a Mongolian, a retired soldier, a sailor, an icon painter and a village peasant boy. Their leader was a defrocked priest; a dignified and educated man who had fallen on hard times. Repin experimented with composition and individual positioning to reflect not only their personalities but also the brutal, backbreaking nature of their labor, harnessed together to haul a 40-ton barge upstream against the current. Only the boy, the newest recruit, rebels against this slavery. Just visible in the distance, a tiny steamship suggests the possibility of a better future. More than 50 years later, in 1929, the People’s Commissariat of Transportation prohibited manual barge hauling, but Volga boatmen continued using the method until the Second World War.

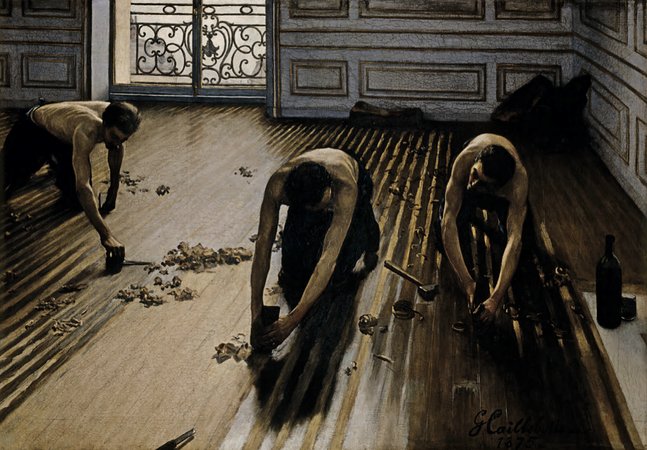

THE FLOOR SCRAPERS

Gustave Caillebotte

1875

As a trained naval engineer, Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94) was interested in the details of the craftsmanship and hard graft involved in levelling out a wooden surface. However, when he submitted this painting in 1875 to the Salon – Paris’s grand annual art exhibition – it was rejected, apparently on the grounds of vulgarity; the jury was offended by its realism. Although by this time rural peasants were considered acceptable subject matter for art, the urban proletariat was not. So Caillebotte turned to the Impressionists and exhibited The Floor Scrapers , together with another version of the same subject at their second exhibition in 1876. In that show his male laborers were exhibited side by side with Degas’s pictures of laundresses. These half-naked men did not escape critical censure; their arms were considered too thin and their chests too narrow. Caillebotte, in one critic’s view, should have interpreted reality more freely: either make your nude beautiful or leave it alone was the message. Painted when Paris was undergoing extensive urban renewal, The Floor Scrapers not only presents an entirely contemporary subject but also approaches it from an unconventional angle. The viewer sees the workers from above, against the light, in a cropped, almost photographic composition.

THE CHILD’S BATH

Mary Cassatt

1893

Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), the only American to exhibit with the Impressionists, often depicted in her work scenes of family, maternity and childcare, or events within the domestic arena. Here she reimagines myriad representations of the mother-and-child theme as an intimate but ordinary bourgeois tableau. Seated on a cushion on the floor, a woman holds a small girl on her lap, a child whose feet just break the surface of the water in the washing basin. The woman has a firm grasp on the girl, the placement of her hands providing another point of contact between the two. The gazes of the two figures unite at the site of action – the washing of the child’s foot – and direct the viewer’s attention to the everyday but tender task, imbuing it with a sense of gravitas. Despite the quietude of the subject, Cassatt’s choices are formally daring, enlivening the subject through a series of diagonals articulated through the pattern in the rug and the insistent stripes of the woman’s dress, as well as the solid cylinders of the little girl’s legs. The steep overhead perspective derives from her deep appreciation of Japanese woodblock prints, as well as situating her work securely within the compositional experimentations favored by her Impressionist colleagues.

PAINTING, SMOKING, EATING .

Phillip Guston

1973

Philip Guston (1913–80) entirely abandoned abstraction around 1968, becoming standard-bearer for the revival of figurative painting in 1970s and 80s American art. His child-like outlines and characters drew on the crude and scabrous comic-book traditions of Popeye and Robert Crumb. This large-scale self-portrait reduces the artist’s body to a bean-shaped head with a single wakeful eye – a recurring image in his late works.The faculties of seeing and thinking are thus emphasized, but this rational ideal is undermined by cravings for junk food and cigarettes. The work was produced at a point in his life when excessive eating and smoking habits had begun to affect his health and capacity to work – the inclusion of "painting" in the title and the pots of paintbrushes depicted by his bedside may imply activity, but his hands are hidden beneath the bedclothes. The looming, unfinished depiction of piled boots adds to the sense of claustrophobia and a furrowed forehead reveals his worry. The light bulb, a standard device of cartoons to suggest inspiration, is seemingly switched of and his signature palette of lurid, fleshy colors completes a sense of morbid physicality.

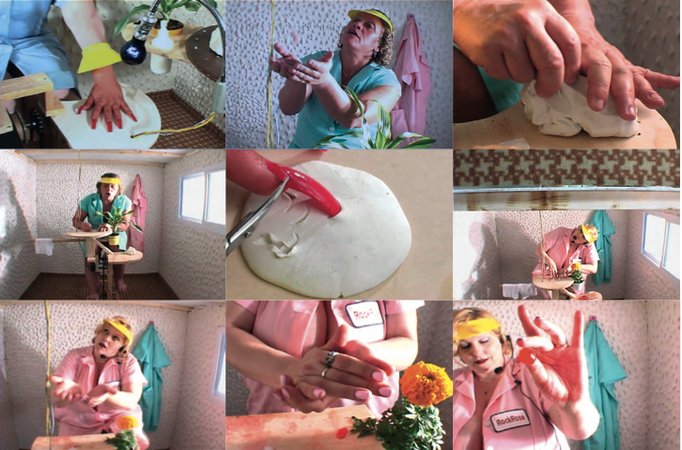

MARY’S CHERRIES

Mika Rottenberg

2004

In a small, makeshift room, an oversized woman in a synthetic overall, of the type commonly worn by cleaners or supermarket cashiers, pedals frantically on an exercise bicycle. Her efforts produce power for an ultraviolet lamp in another room, which is poised over a second woman’s hand, and when lit triggers garish red fingernails to grow at an astonishing rate. The nails are snipped and the clippings dropped down a hole into another flimsy room, where a third woman pounds them until soft and squashes them into balls until they magically transform into maraschino cherries. Rottenberg’s (b.1976) short film is a humorous comment on working-class labour, the mundanity of production industries and the exploitation of women’s bodies – subjects that she explores again, with an even more labyrinthine narrative, in her later video work Dough (2005–6). In both films, the female characters wear name tags on their uniforms that remind us of their individuality, despite their depersonalized and monotonous roles on the production line. In Mary’s Cherries , painted nails were paired with cocktail cherries to highlight their status as desirable yet superfluous decorations, mainly associated with women. Presented in a room where walls and seating duplicate the film’s setting, the viewer becomes a participant in Rottenberg’s fantasy world, inevitably comparing her own body and life to those presented on screen.

COST OF LIVING (ALEYDA)

Josh Kline

2014

At first glance, Kline’s sculptures look like assemblages of found materials. A cleaner’s handcart is arranged with the usual tools of the trade – a large sack for trash, bottles of detergent and sponges – yet among these everyday objects are life-sized dismembered body parts: heads, hands and feet. These have been created using biometric scans of living humans, and the whole sculpture was then created using a 3D printer. The body parts selected are those that relate to the actual job of cleaning, as if the rest of the body is somehow superfluous. The sculpture is part of larger investigation into labour and human capital. The artist interviews people in low paid professions such as janitors and FedEx delivery drivers, and the resulting sculptures, installations and videos are both fragmented portraits of individual workers as well as a broader commentary on their role within contemporary American society. Kline (b.1979) opposes the belief that technological progress is necessarily positive, instead seeing how it has created ever more pressure to function efficiently and ever more sinister means to electronically monitor this. He reflects on the fact that those in the lowest paid jobs – which are often characterized by physical toil and socioeconomic precariousness– are now measured against challenging target outputs. Workers are expected to operate as near superhuman machines, denying their humanity and individualism.

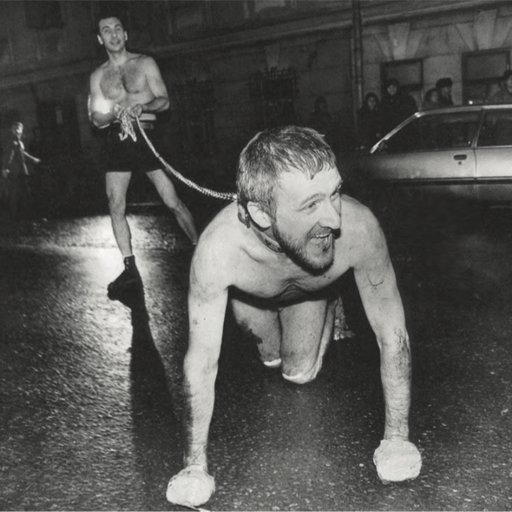

HUMAN MASK

Pierre Huyghe

2014

Human Mask is set in the city of Fukushima, abandoned following the 2011 tsunami and consequent nuclear meltdown. After scanning the devastated landscape, the camera moves inside the one structure that remains standing, a former restaurant. Here it finds a girl alone, wearing a buttoned-up navy blue dress. Her beautiful, if expressionless face is framed by long, silky black hair. However, it soon becomes evident, from the gnarled fingers and furry arms and legs, that this figure is not a person, but rather a monkey wearing a wig and human mask. The film was inspired by a true story of a restaurant in Tokyo, where macaques are trained to work as waitresses performing simple duties for the amusement of diners. Pierre Huyghe (b.1962) transplants the action to a dystopian, yet all-too-real setting. After human life has disappeared, this solitary figure quietly continues to perform her routine: delivering bottles from kitchen to table, patiently waiting to be called upon for the next task. The simian’s gestures – as she plays with tresses of hair, picks her nails or sits with legs swinging – are disturbingly child-like, and compel the viewer to consider how similar to us is this creature in its lonely, toxic world.