Since the president's reported plans to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts and artist-led protests of the Trump administration, the mediasphere has buzzed with opinionated takes on the relationship between politics and art. But for an artist like Hans Haacke, whose irreverent conceptual artworks have sharply and pointedly criticized social conservatives, nationalists, "big-time" politicians, major corporations, and longstanding institutions for decades, controversy (which in Haacke's case, often leads to censorship) is nothing new. In an excerpt from Phaidon's Contemporary Artist series book Hans Haacke, we revisit a 2004 conversation between the godfather of institutional critique and Molly Nesbit for insight into how artists dealt with federal de-funding of the arts during the last Republican administration, the politicizing effects of corporate sponsorship in museums, and how art can become both a tool or weapon.

Molly Nesbit: You and [sociologist Pierre] Bourdieu speak a great deal about what you call the “battleground” of public opinion, its nature and its importance. “Battleground,” of course, makes plain the existence of structural adversarial conflicts in the public sphere. It also implies weapons—means for challenging one’s opponents, one’s adversaries, be they institutional or ideological (those two things now being exactly the same). Bourdieu was fascinated by the way in which you’ve used the techniques of mainstream publicity to produce your critique of its business (and big business in general). The provocation, then, is produced both by the means and the ends—a double challenge.

The particular provocations being discussed by the two of you are now part of the history of the early 1990s. Would you see your challenges in the public sphere to be differently defined now? Are different means of provocation, different formal weapons and rhetorics required? Is the rhetoric of the advertising image still useful to you?

Hans Haacke: When Bourdieu and I were talking about cultural politics in the US and how they’re connected to “big-time” politics, things were far from settled. What we saw as a threat then, has since gained incredible force. More and more, every day, the coalition of Christian fundamentalists and neoconservatives is undermining the public welfare and the American Constitution. Practically all institutions have accepted the domination of the public sphere by corporate interests, many of them without offering much resistance and without embarrassment.

Until the year 2000 the New York art world had reason to believe that assaults on the freedom of expression were foreign to their city. The “culture wars” were fought elsewhere, not in New York. We seemed to be secure. And the art market was humming. New York’s Republican Mayor Rudolph Giuliani taught us not to be so smug. In 1999 he cut the Brooklyn Museum’s monthly subsidy of about half a million dollars (a third of its budget); he threatened to replace the Museum’s Board of Trustees with people of his choice; and he announced he would evict the Museum from its city-owned premises. All this to punish the Brooklyn Museum for including Chris Ofili’spaintingThe Holy Virgin Mary (1996) in this show of the Saatchi collection, “Sensation” (1999). The subtext was that Catholic voters were to be rallied to prevent the election of Democrat Hillary Clinton to the US Senate! When the New York Mayor’s “sensibilities” are offended, the separation of Church and State, and the right to free speech, as protected in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, were no longer considered binding by this former Federal prosecutor! Giuliani believes—like some of his peers in Washington—that he can impose his private or politically expedient views on the country through his hold on public money, i.e. the taxes paid by us. The Brooklyn Museum went to court. Eventually, a Federal judge ruled that His Honor had indeed violated the Constitution. Judge Nina Gershon didn’t mince words. Let me read to you what she wrote in her decision: “There is no federal constitutional issue more grave than the effort by governmental officials to censor works of expression and to threaten the vitality of a major cultural institution as punishment for failing to abide by government demands for orthodoxy.”

In the early 1990s, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art had put together a show commemorating an exhibition that the Nazis had organized in 1937 under the title “Degenerate Art.” Stephanie Barron, the curator of the show, reported in her catalogue that there was “an uncomfortable parallel between” the issues raised by the assault on the NEA and those “raised by the 1937 exhibition, between the enemies of artistic freedom today and those responsible for organizing the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition.” Perhaps because I was born in the country with this infamous past, and because I was myself twice the victim of censorship by a museum, I’ve become allergic to the sort of parallels that Barron saw. In today’s media fog, it’s easily overlooked that there’s something at stake here for all of us. Worrying about freedom of speech is not cool—it doesn’t sell.

"The Business Behind Art Knows the Art of the Koch Brothers," 2014

"The Business Behind Art Knows the Art of the Koch Brothers," 2014

But certainly the revelation of corporate wrong-doing is daily news right now.

Sure, corporate scandals, Enron, WorldCom, etc. are our daily fare. But we get used to them and merely become cynical. And then a war comes along and we get enthralled by a new spectacle. Rarely can we pay attention to more than one big item at a time. That may indeed be what the current Bush administration is banking on. They’re endowed with an incredibly combination of ruthless cunning and arrogant naivety. It’s an advanced case of hubris. Except for a few, we’re all going to foot the bill.

It boggles the mind that within eighteen months of the attack on the World Trade Center, George W. Bush has squandered the outpouring of sympathy for the US around the world. Instead of sitting on the budget surplus that he had when he took over, with frenetic tax cuts for his wealthy cronies he’s piled up an ever-larger mountain of national debt. In 1992 I called a work about his father’s version of the redistribution of wealth Trickle Up. The son has turned it into a flood. The readers of this exchange between the two of us will know more by the time it’s published. I hope that then things will be a bit brighter.

So the challenges are still the same. What about the critical weapons you use in your art? Mostly you still use elements found at the site in which you happen to be working.

I often work with the specific context of the place for which I produce a piece—both the physical as well as the social and political context. They’re part of the materials I work with; they’re like bronze or paint on canvas. In the place for which a project was conceived, the work has a charge, a performative quality, so to speak. When a work of this nature is shown outside its original context, background information needs to be provided so that the viewers can understand the references and the impact it might have had. Many people think this isn’t necessary for other kinds of art. Of course that’s a fallacy. We know this from personal experience.

In the 1960s, when Minimalist and Conceptual artists first emerged—Pop art had already gained a certain market share—their work was hotly contested. Many people dismissed it as utter nonsense. Do you remember that Abstract Expressionism was once suspected of being a Communist conspiracy while, at the same time, the CIA employed it in the Cold War? It’s hard to believe today that a Jackson Pollock painting could have played a role as a cultural weapon. People who didn’t live through that period cannot have a sense of the significance these works had, what was at stake for those who made them and for those who supported or dismissed them. It’s for historians to expose the many meanings and often conflicting roles that artworks have played over the years of their existence. But historians can only offer the views that are compatible with their own time.

We know that the way we think at any given time doesn’t, and shouldn’t, frame a work forever. But this allows us to enlarge upon the matter of communication in the public sphere. Let’s look at the different strategies you’ve used over the years in your work. Let’s compare GERMANIA in the German pavilion in Venice with MetroMobiltan (1985) in terms of the way in which your provocation or exposé is set into motion formally and physically. In Venice, it’s rather like looking at a Cubist picture. You’ve put various symbolic forms together and asked us to read them against and through the ripped-up floor. One sees the violence of the ideological battle physically present in the disruption, giving us a way to hold it in the mind as a memory. The adversary becomes a wreck. MetroMobiltan is very different. It’s more like looking at the blocks of a well-designed advertisement from the mid-1980s. You’ve rearranged the elements from the display culture of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art’s banners, its facade—in order to expose the financial interests supporting the museum. The museum reveals its own moral weakness once we examine the parts, but we have to work to pry the elements apart. There’s no actual formal violence, just the compression of two opposites into the same facade. The explosion happens conceptually. But in this case you work in the present on the present. In Venice you worked in the present on the past. Is this shift due to a different public being present there? Or is your sense of the work of art’s place in time changing?

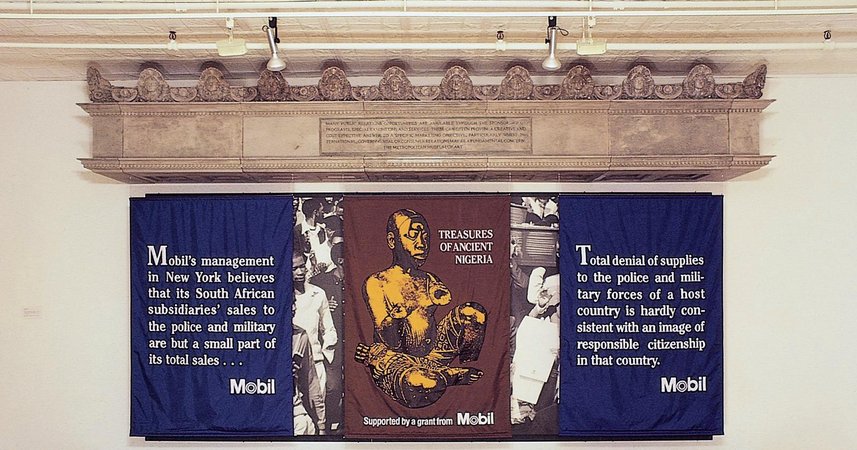

I don’t believe that the public of the Biennale and that of the Metropolitan Museum are so different. The Museum is an institution with a very rich past—“rich” in the multiple meanings of the word. My mock rendition of its facade speaks of that. On its entablature I quote from a leaflet by the Museum with the cute title: The Business Behind Art Knows the Art of Good Business. In a nutshell, it explains the rationale behind the involvement of corporations in sponsoring culture. Corporations don’t have aesthetic desires. They’re set up to promote the financial interests of their shareholders. And that includes not only promoting the company’s image but, as the current crop of executives sees it, making sure institutions that receive their support do not engage in activities that could cast doubt on their “responsible citizenship.” A Mobil PR-man once said: “These programs build enough acceptance to allow us to get tough on substantive issues;” Mobil and Philip Morris have both tried to interfere with shows of mine. Institutions usually don’t let it get that far. Self-censorship is a given. MetroMobiltan is a collage of disparate elements, put together like the Surrealist’s “exquisite corpse,” without smooth transitions. It’s the viewers’ task to understand the conflicts between these elements and to draw conclusions. It’s a technique similar to that of Bertolt Brecht.

MetroMobiltan, 1985

MetroMobiltan, 1985

But the disruption becomes much more physical in the German pavilion.

Yes. There’s a fundamental difference between how we react to physical reality—in this case the breaking of marble slabs—and mere representations of violence through a photograph. Neither approach is possible or appropriate in every situation.

Viewing Matters: Upstairs (1996) at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, was again very different in approach. Here, you found a way to work with others in a museum setting. It’s no surprise to find you working at the Boijmans. Over the years you’ve often worked on the site of the museum, unmasking what Bourdieu would call its “invisible structures.” MetroMobiltan would also be a good example of that or Manet-PROJECT ’74 in Cologne in 1974. But the Rotterdam project didn’t get you into trouble.

Interestingly, some curators and museum directors in The Netherlands were outraged!

Why?

I believe they thought I didn’t treat the works with the proper respect.

What did they mean by “proper?”

I think they were offended by my bringing the storage racks from the basement upstairs to the bel étage and presenting the collection as it is housed downstairs: according to how best to save space, irrespective of medium, period, monetary value, and historical or aesthetic significance.

Literally revealing the invisible structure.

Yes. Presenting the works they cherish in this seemingly disrespectful fashion they considered insulting both to them and to the works. I meant to demonstrate that every presentation of works from the collection is inevitably a highly selective choice, driven by an ideologically inflected agenda—as was mine. It’s often assumed that what we get to see on the walls of museums is a disinterested display of the best works, and represents a reliable account of history. This, of course, is never the case. The canon is an agreement by people with cultural power at a certain time. It has no universal validity.

They’ve cleaned it up, as André Mairaux told us at great length in his text on the museum without walls, the Musée imaginaire (1947). But your Rotterdam project had other elements to it, didn’t it?

There were a number of other significant components to this show. I called it Viewing Matters, both in the sense that it matters to look, and that there are things, or matters, to examine and choose from—like in a department store. For the walls, around the central complex of the storage racks with the indiscriminate display of unrelated works, I selected specific paintings, sculptures, photographs, and objects of all sorts, according to five themes: Artists, Reception, Power/Work, Alone/Together/Against Each Other, and Seeing. Throughout the show I provided no explanations. Had I done so, I would have undermined the technique of causing creative friction that has been attributed to the Comte de Lautréamont: juxtaposing normally unrelated objects, such as an umbrella and a sewing machine on an operating table. This was his prescription for producing new and unexpected meanings, adopted by the Surrealists with a similar intent in the parlor game “the exquisite corpse.”

Then you made a book to accompany and survive the show. Often your books are an important part of the work: they provide another ground with which you, the artist, can communicate with the public.

With the book, I tried to do something similar to the exhibition. I emphasized the peculiar nature of a book’s physical properties and design: layout, page-sequencing, printing techniques, the qualities and flaws of photographic representation. I was lucky to be able to work on this with Paul Carlos, a very gifted designer in New York who has a rare sense for creative collaboration. The book is not meant to be a documentation of the show. However, like in the exhibition, I positioned images in relation to each other as a motor to create meanings that they wouldn’t have had in isolation. We played with varying degrees of photographic resolutions and digital techniques. This highlighted the technically contingent quality of reproductions. We accepted reflections on the surface of paintings and protective glass as they appeared in the photos, and we accepted angled views of planar works. In short, we violated standard design rules. It was a lot of fun.

Taking Stock, 1983-84

Taking Stock, 1983-84

Were you thinking about turning the book into a musée imaginaire, or making use of another of Malraux’s ideas—that works of art exist in the museum as a confrontation of metamorphoser? The works undergo yet another change of state when photographed. And there the metamorphosis becomes even more dramatic because of the way in which photographs flatten form and distort color. Was the museum-book as an engine of metamorphosis (and alienation) one of your working concepts?

The museum as an institution that shapes our sense of history was certainly on my mind. I have only a vague memory of Malraux’s musée imaginaire. I believe he spoke about the homogenization to which works are subjected in books, due to the standard size of the printed page and their reproduction in black and white.

Yes, and the strangeness of the close-up also worried him.

In many instances in the book, I retained the size of the works relative to each other. Small works were reproduced small next to big works that were reproduced large. But I also played with close-ups and excerpts and collage.

And there’s the shifting between black and white, and color.

Yes. There are color pages, pages with black and white, and pages with both—or a monochrome color.

You book calls to mind another compendium too, in part because you included so much of his work here, and that’s the Boîte-en-valise (1935-41) of Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise became a portable museum of his own work, which no museum in the world at that time would have shown. It’s very personal. How does the Boîte function in the context of your Rotterdam project?

Duchamp was, of course, the first artist to think about the aura that surrounds art and artifacts, and the power of context. As we know, they fundamentally affect the way in which we look at objects. The paintings on the storage racks didn’t look like much (maybe that was behind the disapproval I encountered). In 1972, Marcel Broodthaers continued Duchamp’s project with his fantastic exhibition Musée d’Art Moderne, Department des aigles, section des figures (Kunsthalle Düsseldorf). I was glad the Boijmans had a good number of works by both of these iconoclastic artists. They allowed me to introduce notions of the contingency of meaning and to undermine universalizing assumptions.

Perhaps there’s something else involved as well. While Duchamp was an ardent explorer of what he would call the “non-retinal dimensions,” he was also interested in the ways in which retinal matters can be extended. For him these two preoccupations went together. The non-retinal dimension of your own work is probably the one that has been most emphasized over the years, in part because you’ve asked us to think. Your earlier work using Duchamp’s example—I’m thinking of Broken R.M. … (1986) and Baudrichard’s Ecstasy (1988)—involves more knowing than seeing. Duchamp is there as a symbolic form first and foremost. Yet at the same time a retinal dimension is quite evident. In the Rotterdam project it dominates. There you give us more something to look at than something to read.

In the section of Viewing Matters I called “Seeing,” I included a walk-in camera obscura. Once your eyes had adjusted to the darkness, you could see the street with cars passing by and the church across from the museum. Of course, they all appeared upside down. During the opening of the exhibition, the head of the installation crew told me with great excitement that he and his kids had just seen lightning in the camera obscura.

It’s very interesting conceptually to think about this work together with DER BEVOLKERUNG (TO THE POPULATION, 1999), in which you brought soil from various different sources into the Reichstag. The seeds and plants that inevitably arrived with it will be allowed to grow there forever. But the historical ground from which museum curators choose their exhibitions is just as charged as the soil that came to the Reichstag. You could even say that it’s spiked. It has its toxins and its late bloomers.

This project, like GERMANIA, did not spring from museum conditions. At the Reichstag, another kind of communication has been attempted, and another kind of disorder is produced. This time it stems not from violence but from the eruption of natural growth, natural processes, from mother earth. You have a different kind of frame, a different kind of ground. As an American looking at this I say, “My god, it’s incredible! Hans Haacke has the ground of the state on which to make art—and the state itself has given it to him!” Such a thing wouldn’t be possible in the United States. As you’ve spent many decades living in America, what does it mean to you for the German state to give you a space like this for your work? Do you find it extraordinary? Because, you know, you’re not exactly a state artist in most people’s minds.

Some do now think of me as a state artist. As you say, it is indeed uncommon for a parliament or the commissioner of a pavilion at a Biennale to allow national showcases of such symbolic significance to be used as a forum for the discussion of public issues. I give great credit to Klaus Bussman, the German Commissioner in 1993, for inviting Nam June Paik and me to represent Germany at the Venice Biennale. Even though Paik had lived and worked in Germany, he’s a resident of New York. He’s not a German citizen. And I’d been living outside of Germany for almost three decades and hadn’t particularly ingratiated myself with the powers that be.

Did that in any way come into play when the commission for the Reichstag was being decided?

It may have played a role. I was the last of nineteen artists to be invited, and, as we know, my proposal did, in fact, cause problems.

“Hommage à Marcel Broodthaers,” installation view at Documenta, 1982

“Hommage à Marcel Broodthaers,” installation view at Documenta, 1982

And as an artist of conscience working for the state, what changed when you found yourself speaking for both the state and to the state in these different commissions? The Venice pavilion was a temporary installation, a temporary conversation between you and the state and your audience. But the Reichstag is something else again. It has created a conversation that could and should be heard for centuries. As a stage for contemporary art this is extremely unusual. Most contemporary artists couldn’t imagine a situation where their work would be shown in a public place for more than six months, much less decades, much less centuries. But when you work for a state that sees itself as having an eternal life, conceivably your work can have an eternal life too.

Attitudes towards the state in a liberal society are complex and differ between countries, especially between the US and Europe. Traditionally, Americans—particularly the more conservative ones—are hesitant to cede powers and responsibilities to the Federal Government. In the wake of the French Revolution, Europeans, on the other hand, have put the state in charge of practically all matters of public welfare. Public money—which always means taxpayer’s money—is used to underwrite the res publica, the public cause (Republic). As part of this understanding, culture has been unquestioningly subsidized by the state in Germany and other European countries on a scale that’s simply unimaginable in the US. It’s a relatively new custom that the organizers of costly exhibitions are emulating the American model and making appeals for corporate sponsorship, even though they know full well that it limits their curatorial independence.

Every artists who exhibits in a public institution is, in a way, a state artist. By accepting the commission from the Bundestag, I allied myself with an institution that constitutes one of the major pillars of German democracy. My work in Berlin obviously wasn’t meant to endorse this or that political party. And it wasn’t perceived as such. The opposition to it crossed all party lines. The Bundestag Art Committee charged the invited artists to address the history and the political significance of the site. I think I did that. I alluded to the troubled German past and to the present debate over German citizenship, and the responsibility of the Bundestag to all who live on German territory. I wanted the project to be an ongoing participatory process. Taking politicians at their word turned out to be provocative.

And there was one word in particular that you picked up on. The controversial component of the piece was to present an alternative to the Reichstag’s inscription “DEM DEUTSCHEN VOLKE” (“TO THE GERMAN PEOPLE”)with “DER BEVOLKERUNG” (“TO THE POPULATION”), written in neon light.

The third article of the German constitution of 1949 speaks about equality: nobody should be discriminated against or favored because of their gender, origin, race, language, birthplace, their religion, beliefs, or political opinions. Obviously, this is based on the Declaration of Human Rights of the French Revolution. Politicians usually claim to have everybody’s interests at heart. They invoke the Bevolkerung (population) in every speech. But if that inclusive word is played back to them and related to the historically burdened word Volk (people), as it was with this project, attitudes. change. All of a sudden the population becomes suspect, particularly to conservatives. For non-Germans, “people” is an innocuous word. However, because Germany became a unified nation only late in the nineteenth century, in the myriad principalities and kingdoms the word Volk implied ethnic unity and a common culture. It was this exclusive tradition that the Nazis tapped into. Blood lineage became an issue of life and death.

It does still have a currency, doesn’t it? It still has political force behind it of some kind. It’s not a dead word.

Yes. The revolutionaries of the failed uprising against the German princes and kings in the mid-nineteenth century were inspired by the French Revolution and its emancipatory goals. And in this context it meant, and still means, “everybody.” Unfortunately, the understand of Volk in the tribal, volkisch sense is not yet a thing of the past. AS in other countries there are nativists in Germany. Neo-Nazis beat up people who don’t look sufficiently German to them. And conservative politicians don’t shy away from making veiled appeals to an undercurrent of suspicion regarding people of other ethnic and national backgrounds—not unlike the racist code words with which politicians in other countries try to win elections. The Christian Democrat MP who led the campaign against my project—like so many in his party—is a fervent opponent of the liberalization of the German citizenship laws. He and his supporters want to hold on to the jus sanguinis, according to which citizenship depends on parentage rather than place of birth.

You might say that we’re not speaking so much now about an artistic strategy of provocation or contradiction as about the promotion of a concept of a people. The weapons we talked about earlier should maybe at this point be called “tools.”

Yes, I’d rather use the word “tool” than “weapon!”

Collateral, 1991

Collateral, 1991

Swords will turn into gardening tools at this point in our interview. With DER BEVOLKERUNG you allowed other people to choose where the soil comes from. Did you do this so it would change form in a way that you couldn’t have imagined?

It’s unpredictable. It’s a communal project. Many opponents in the Bundestag accused me of laziness, claiming that I didn’t even do my own work. But now, more than 200 members of the Bundestag have participated, and the project has gained a degree of popularity. Looking back, it’s hard to believe that it caused such a bitter national debate and that the Bundestag spent more than an hour, in full session, arguing over it. Eventually, it’s realization was approved by the slimmest of margins, by a vote of 260 in favor and 258 against. As I imagined, many MPs involved people from their election district in choosing where the soil should be collected from. And so it became a participatory process even at the district level. Wolfgang Thierse, the President of the Bundestag, inaugurated the project with earth from the Jewish cemetery in his district in Berlin. Several members brought soil from the grounds of former concentration camps. There’s earth from a house that had been burned down because Turks had lived there, and from other places that are relevant to the ongoing debate over residents who don’t have German citizenship (currently more than nine per cent of the population). Some MPs spiked the soil with seeds. It’s fantastic. Nobody knows how it will develop.

Are you going to leave instructions for the kind of garden it will become in the future? Will it ever be trimmed or cut down?

No, no gardening whatsoever. No watering, no weeding, no cleaning, no nothing. It’s to be left alone. The coming together of earth and plants from all over Germany in a building with the highest security provisions makes this a unique ecosystem. With the soil, a host of insects, worms, and snails arrived. The pigeons in Berlin have also contributed their share.