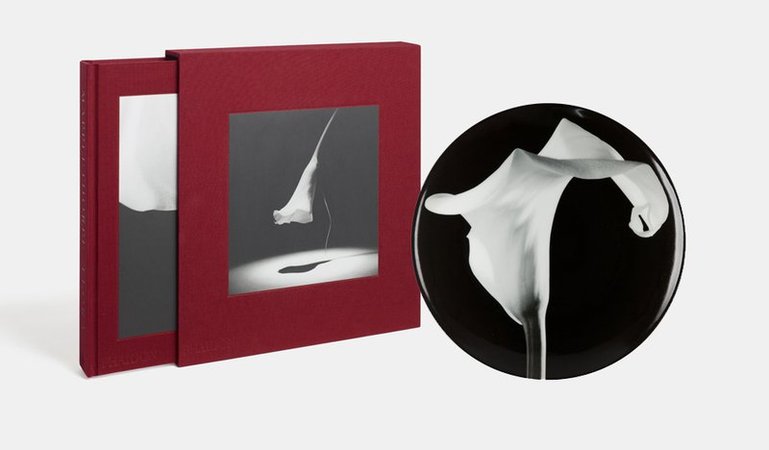

While he’s best known as the forward-thinking New York Times architecture critic who championed figures like Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid , Herbert Muschamp was also a keen observer of and participant in New York City’s vibrant gay culture, the same scene that allowed the talents of a certain Robert Mapplethorpe to bloom. In this 2006 essay, written just a year before Muschamp’s death and excerpted from Phaidon’s new compendium Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers , the critic delves into the "exceedingly democratic" impulses behind a more meditative (vegetative?) turn in Mapplethorpe’s famously provocative body of work . Check out a few samples from the book here and here , and purchase the entire book here to read Muschamp’s essay in full and see all of Mapplethorpe's incredible, sensual flower photographs.

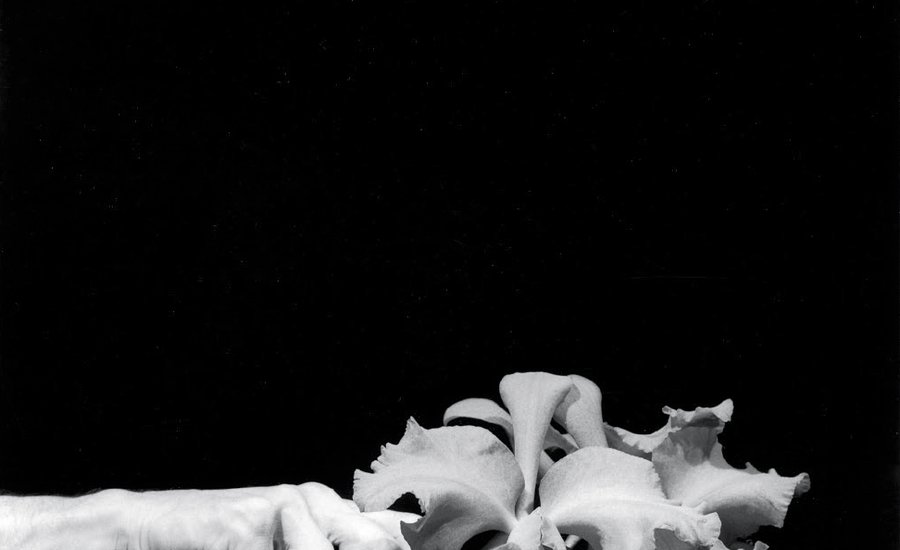

It takes a practiced exhibitionist to make a great voyeur. [Robert Mapplethorpe’s] flower photographs are an embodiment of this principle. The flowers are the photographer/voyeur as he exists in another part of his life, playing the other role. If he were not framing the subject matter, he would be practicing poses of his own. Instead of moving lights around, he would be adjusting the angles of his face and torso to take advantage of the available source. Stems are the preparation; they connect the off-camera groundwork to the event. The bloom is the event, and only secondarily an object. It is a fleeting experience in the life of an organism. The photograph is in this sense an action shot; a depiction of the flowering as well as a flower, a climactic occurrence in time, a process every life must pass through before deflowering can take place.

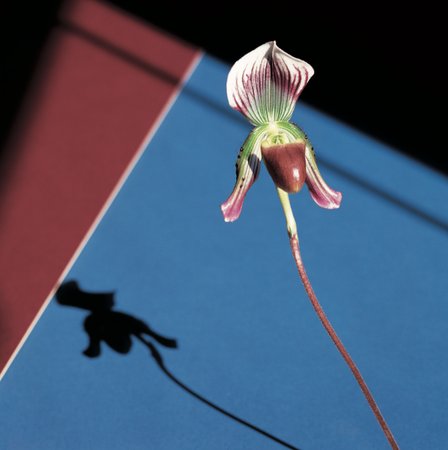

Mapplethorpe’s floral preferences are exceedingly democratic. Irises, daisies, tulips, and other common species are posed with as much regard for character as orchids and lilies. This egalitarian outlook makes it almost possible to forgive Mapplethorpe for establishing the orchid as a plebian luxury of our time (it having now become illegal for any New Yorker’s birthday to pass without at least one ceremonial appearance by The Orchid). The unexceptional mum emerges as a mandala of potentially carnivorous tastes, with petals that delicately unfold to grasp the viewer’s attention, and maybe feed upon his eyeballs.

Orchid

, 1986

Orchid

, 1986

Mapplethorpe’s society of vases is also class-blind. Those of expensive Scandinavian crystal are possibly the least exceptional. Outside the realm of perfume, it is seldom within art’s power to triumph over good design. Like dancers, Mapplethorpe’s flowers want a less-studied costume so that their innate power of gesture can be articulated fully. Then we pick up their scent, even through the eyes alone.

This fragrance often recalls clouds of incense in a church. The religious dimension is seldom absent from these images, if you allow them to speak for old memory. The altar flowers this week have been given by X in loving memory of Y. The lilies have begun to turn before the choir’s wardrobe mistress is allowed to take them home for herself. The roses remain undefiled, but show signs of wilting under Virginity’s sublimated strains.

Flowers convey the attributes of saints as well as aesthetes. Martyrs walked down the Via Sacra holding lilies, if not poppies, when their sacrifice earned them a privileged spot in the Christian version of the afterlife. Preliterate society was as educated in the meaning of these emblems as our postliterate contemporaries are in the language of corporate logos. We may no longer need the saints; the symbols of their attributes will suffice.

But, as with Warhol’s work, it is the compulsive quality of Mapplethorpe’s images that evokes the strongest resemblance to religious practice: the repetition; the ritualistic return to certain types of flower—as if by replaying an image again and again, one could ultimately master a recurring source of frustration, though not necessarily know whether one wants to be the giver or the receiver of these lavish tributes (again, as with Warhol, guilt is activated by the triggers of desire).

Shortly before he died, Mapplethorpe sent his friends copies of a particular tribute to remember him by. The picture, in black and white, depicted a bunch of tulips lolling languidly out of a squat black vase. The arrangement was framed by the sweeping curve of an opening, a white portal to the gray beyond. The circumstances of his distributing this image allow it to be read as a reflection on approaching death, as well as a thank you for those who helped him reach that portal with the feeling that his life had been appreciated. He could know and accept that he’d been loved and, moreover, that he was lovable, and that being abandoned is ultimately not our fate.

Tulip

, 1977

Tulip

, 1977

Click here to learn more about our Mapplethorpe: Flora gift set.