While the art world is abuzz over Mexico’s contemporary scene filled with artist-run spaces, underground schools, and a healthy community of local and international artists, we must remember that Mexico has a long—ancient, really—history of art. One of its greatest movements in the 20th century was the “Mexican Renaissance,” a government-funded, multi-decade outpouring of creative expression and energy following the Mexican Revolution. It was similar to, but predated, FDR’s network of alphabet soup agencies which employed thousands of artists and craftsmen. Below we’ve excerpted a brief history of the movement from Phaidon’s Art In Time, a collection and timeline of art history new and old.

The term “Mexican Renaissance” is used to define the two decades of artistic production following the Mexican Revolution (1910–21). With the return of relative peace, newly appointed Secretary of Education José Vasconcelos implemented a program of state-sponsored art patronage to stimulate national cohesion in the country. The highly didactic technique of murals was especially favored, and Vasconcelos appealed to artists such as Diego Rivera (1886–1957), José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974) to realize large wall paintings in the country’s main cities. Inspired by Italian Renaissance frescoes as well as by Mexico’s own tradition of muralismo to convey political and religious messages, the artists created murals with a decidedly messianic tone. The violent years of the revolution were often portrayed as a necessary step towards a fairer society. Similarly, indigenismo, or the recognition of Mexico’s indigenous identity, represented a central theme.

Diego Rivera’s mural Epic of the Mexican People in their Struggle for Freedom and Independence is a monumental mural covering the walls of Mexico City’s National Palace. Rivera spent two years working on the project, the narrative of which runs through Mexico’s pre-Colombian history and the Spanish Conquest all the way to the Mexican Revolution. It culminates in a triumphant view of modernity, when industrialization and class struggle pave the way towards a radiant future, indicated by the towering figure of Karl Marx.

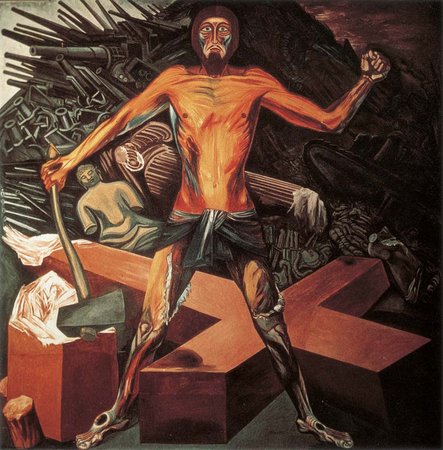

Even though most Mexican muralists shared a leftist sensitivity, the movement itself was far from monolithic. Orozco and Siqueiros had fought in the revolution, and their representations of the country’s recent past and future prospects were decidedly bleak. Techniques also varied. Orozco stayed largely faithful to the fresco, Rivera developed a wax-based technique, and Siqueiros—the most experimental of los tres grandes—experimented with industrial materials such as car lacquer.

Muralism became the emblem of Mexico’s cultural Renaissance, and from the 1930s its artists received international commissions. Orozco completed a large fresco cycle at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, entitled The Epic of American Civilization (1932–34). The messianic tone of the fresco climaxes in Modern Migration of the Spirit, in which a crucified Christ resurrects from the ruins of ancient and Christian civilizations. Holding an axe and defiantly raising his fist, Orozco’s Christ of the Apocalypse becomes the hero of post-ideological times, sharing more with ideals of male militant bravado than with traditional Christian iconography.

Although the Mexican Renaissance is largely associated with murals, canvas paintings remained a central practice. Frida Kahlo (1907–54) developed an oeuvre in which intimate emotions co-exist with political concerns. The Two Fridas is as much about her physical and emotional pains as her identity as a mestizaje, ethnically and culturally mixed. The self-portrait was also used by Rufino Tamayo (1899–1991) to reflect on his Indian identity. Tamayo was critical of Muralism’s superficiality in dealing with nationalism. Instead, he and artists such as María Izquierdo (1902–55), who used natural light and often made their own pigments, perceived themselves as more faithful to Mexican traditions.