Somehow able to solve the problem of wet paintbrushes stuck to frozen canvas, Canada has managed to produce a littany of excellent painters, chief among them the inimitable Agnes Martin, the recent subject of a wildly popular Guggenheim retrospective. Vitamin P3, new from Phaidon, profiles three new but no less interesting Canadian painters—Julia Dault, Sascha Braunig, and Elizabeth McIntosh—mashing up portraiture and abstraction, innovating on the trompe l'oeil, and exporing geometric abstraction. Check out their entries from P3 below.

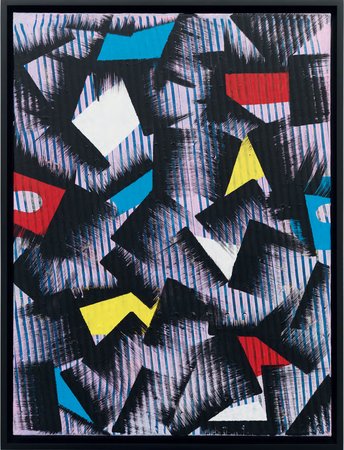

JULIA DAULT

Born 1977, Toronto, Canada. Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Julia Dault’s paintings seem particularly concerned with the fact of their own making. Simultaneously methodical and gestural, they exude a calculated self-awareness, walking a fine line between painterly craft and commercial design. At first glance, her colorful palette of abstract geometries and optical effects presents a relatively flat, two-dimensional scenario, reminiscent of a fashion textile or graphic print. But on closer inspection the work draws the viewer in, slowly revealing the process and marks of the artist. Dault paints in both oil and acrylic, using unmixed colors straight from the tube. Instead of traditional brushes, she often employs a rubber comb or squeegee. Developing vibrant, Technicolor patterns in the first layer that she applies to the canvas (or leather or vinyl), she then paints over them in a solid, usually neutral tone, using the comb or another tool to remove areas of still wet paint. This technique reveals the color beneath in rhythmic patterns or gestures—such as in the painting White Heat (2015)—giving unexpected depth to the composition.

Dault’s process provides what we might call productive constraints. However, the paintings are not “rule-based” in the sense that we are accustomed to when thinking about conceptual or minimal art. Rather, these constraints seem to emerge from the implicit properties of the tools and the medium itself. The paint and the comb make plain (or “evident”) the status of the paintings as the end products of a process, rather than a painterly illusion. This process results in work with a somewhat literal quality—the effect is demonstrated, not obscured—and even the gestural shapes that Dault makes tend to leave a mark that is as much an index of the tool as an expression of the hand.

The titles of Dault’s paintings are derived from popular culture, including music (Color Me Badd, Major Lazer, Party Mix), television (The Freshmaker) and film (Indecent Proposal). With only a few exceptions, her reference points are all from the 1980s and 1990s, underlining the nostalgic quality of many of her works. Indeed, the titles seem to snap into focus other latent aesthetic cues from those decades, conjuring up faintly remembered Esprit jumpers, swatch watches and Yamaha DX7 synth lines. The experience makes for an irresistible rhythmic formula: the visual equivalent of a Stock, Aitken, and Waterman hit. In this sense, Dault is also playing with our assumptions about “abstraction.” By routing her aesthetic choices through media, fashion, and textiles, she manages to deliver abstraction-as-pop art. Recent collaborations with fashion and merchandising brands such as Everlane, Massif Central, and Jeremy Laing only goes to show how well such an aesthetic can translate back into the texture of everyday life.

– Timothy Ivison

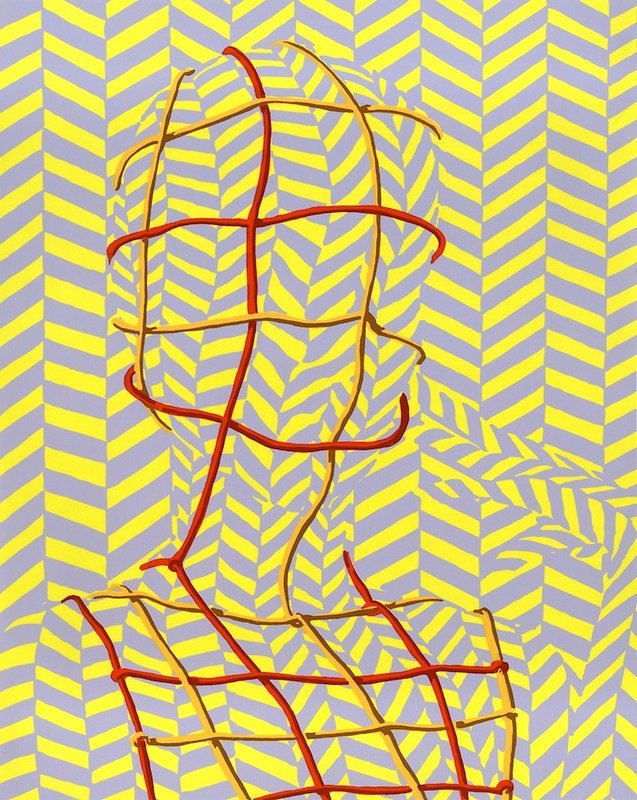

SASCHA BRAUNIG

Born 1983, Qualicum Beach, BC, Canada. Lives and works in Portland, ME.

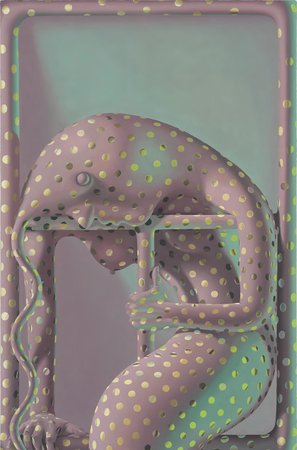

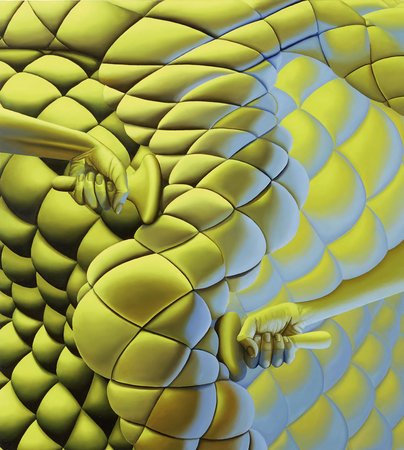

Sascha Braunig’s paintings thrive on a multiplicity of uncanny forms and forces: they play with light and shadow, flexibility and rigidity, fullness and emptiness, push and pull. These dynamics are made to negotiate with one another on the flat linen-covered board on which she paints. Braunig is a master of the trompe l’oeil, her visual effects ranging from the creation of depth and perspective to fantastical bodies, lighting and even movement, all rendered with carefully synchronized color palettes.

In Warm Leatherette (2015), a sinuous form covered in quilted material snakes across the centre of the image against a matching background. Careful contouring gives the impression of the leatherette being wrapped around bulging flesh or packed wadding, its folds offering an opportunity for intense light-and-shadow effects. A pair of forearms with finely detailed hands pushes stylized burnishing tools into the quilted body, apparently working it into a more curvy shape. Painted in bilious yellow, the subject is lit by raking light which causes bluish grey highlights and deep black shadows. It has a vivid luminosity, which produces a kind of visual giddiness in which the eye attempts to capture the combination of form, color, and suggested movement at play in the image. Although Braunig’s aesthetic and lighting effects share a smoothness with digital imagery, she paints from “life,” making small clay models for her subjects and illuminating them in her studio with bright lamps and colored gels “inspired by over-the-top movie lighting.”

The winding form in Warm Leatherette performs the contrapposto of classical statues or the popped hip of contemporary fashion models. Braunig has said she is interested in the way “the female body is perpetually abstracted, reduced, distorted, or compared with inanimate objects” in art and culture. Her paintings take up this concern, with forms that allude to female bodies, but also suggest the possibility of evolved species. Saccades (2014), titled after the term for the rapid motion of the eyes between fixation points, depicts a form resembling a human head, made of pearls or white beads, set against a background made of the same stuff. Rifts and protrusions in the head’s surface hint at facial features but ultimately, the portrait remains blank. Braunig has described her subjects as “Ur-characters” and “portraits of a state of mind or a potential state,” but words don’t seem up to the task of defining these states, and whatever they are is best expressed by the paintings themselves.

In La Maitresse (2015), Braunig differentiates the figure from its ground, painting the optical illusion of an anthropomorphic mesh silhouette stretched over a frame. The rubbery webbing, a humanoid form voided of any fleshy matter, casts a shadow on the orange ground while its surface gleams in the stark lamplight. It seems almost alive, vibrating with the strain of being pinned so tightly and threatening to escape its confines by flinging itself far away. For Braunig, the ambiguity that surrounds the vitality of her subjects is an essential part of her work, as she explains: it is “important that there is a tension between their lifelessness and possible lifelikeness.”

– Ellen Mara De Wachter

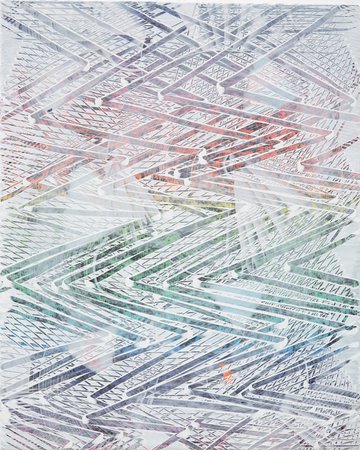

ELIZABETH MCINTOSH

Born 1967, Simcoe, ON, Canada.

Using repetition of basic forms and pure saturated color, Elizabeth McIntosh has been exploring abstraction for over twenty years. Moving beyond the conventions established by modernist abstract painting, she is seemingly unconcerned with trying to “resolve” the image. Instead, she provides an open-ended response to traditional hard-edged abstraction. Teetering between finished and unfinished, figurative and abstract, raw and refined, there is something tangible about McIntosh’s paintings despite the fact that shapes linger without resolution. Take, for instance, With the Moon Under My Arm (2015), where the breast of the reclining blue figure in the foreground reappears as the yellow moon above. For McIntosh, painting is a deliberately undefined journey. She works in a spirit of play where aesthetic development is not contingent on beginnings or ends, but is continually renewing itself. The decisions she makes are formed through an instinctive process that varies from painting to painting.

McIntosh often begins by priming the canvas with either white base coat or occasionally black gesso, progressively filling the surface with colored shapes until it is enveloped in pigment. From this starting point, she goes on to apply numerous subsequent layers and over-painted forms. For example, in Batts Rock (2015), blocks of bold orange and yellow sit underneath a semi-translucent female figure, reclining on a sofa. The colors seem to warm each other up or cool each other down, and there is no clear, balanced composition but a symbiosis between the parts. McIntosh’s rigorous compositional use of color has become the linchpin to her paintings. For example, in Tequila Sunrise (2015), the application of warm, opaque, purples and browns, nestled against the sketchy pinks and yellows, set against the more graphic blue and red lines, harnesses the whole composition and carries the viewer through the picture. The shards of color waver and feel impermanent, giving the work an improvisational feel. Looking at McIntosh’s paintings one might think of the early Cubists (Braque and Picasso) but the artist re-appropriates these reference points to create a new, twenty-first-century Cubism. Through soft edges, awkward shapes and intriguing underpaintings, her finished paintings resist the finality of rationalized abstraction.

Collage is also an important influence on McIntosh’s painting and in her sketchbooks she creates collaged drawings of different patterns that often end up as one of her large-scale paintings. On a few occasions, McIntosh has also created collaged installations. In an exhibition in 2011, “Violet’s Hair,” at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, she covered a room from floor to ceiling in sheets of colored paper, tacked to the wall in patterns. As with some of her paintings, McIntosh worked in a shallow pictorial space, decisively arranging and re-arranging forms over the colored sheets. The resulting holes or “cut-outs”—a nod to the late work of Henri Matisse (1869–1954)—allowed flashes of color to peek through at various intersections, paralleling McIntosh’s painting process.

– Leila Hasham

[related-works-module]