Called interchangeably the “father” or “inventor” of video art, Nam June Paik (1932-2006) single-handedly reconstituted television as an artistic medium. Until Paik’s pioneering efforts of the early '60s, TV sets were considered home electronics or (depending on their size) pieces of furniture. Over four decades, Paik used TVs not only as sculptural components in his work but furthermore exploited their technology as a means of artistic expression, and his inventiveness gradually extended to video, synthesizers, lasers, and beyond. Of one invention, the Versatile Color TV Synthesizer, Paik described its compositional possibilities in terms that made clear the artistic nature of his ambitions:

The Versatile Color TV Synthesizer

This will enable us to shape the TV screen canvas

as precisely as Leonardo

as freely as Picasso

as colorfully as Renoir

as profoundly as Mondrian

as violently as Pollock and

as lyrically as Jasper Johns

With the landmark survey "Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot" now at the Asia Society (through January 4), here is an introduction to the singular art, and life, of Nam June Paik, whose influence today is felt in the work of artists as disparate as Haroon Mirza and Cory Arcangel.

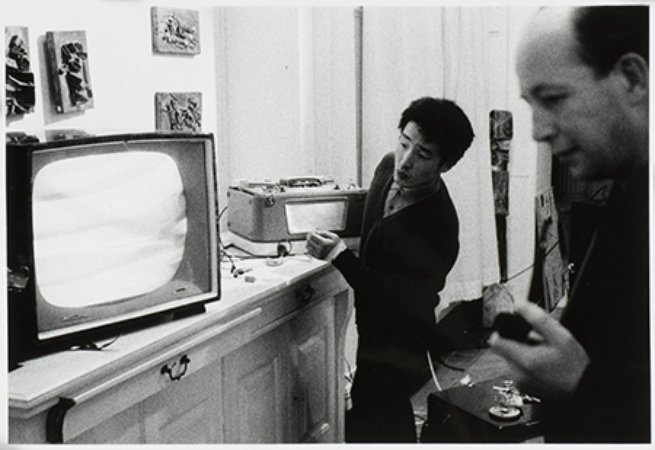

BEGINNINGS IN PERFORMANCE "Exposition of Music – Electronic Television" (1963)

"Exposition of Music – Electronic Television" (1963)

Born in Korea in 1932, Paik was the youngest of five children. He began taking piano and composition at 14; at 15, he discovered the work of composer Arnold Shönberg, whom Paik called one of his two main influences (the other being Karl Marx). The Paik family fled the Korean War, spent a year in Hong Kong, then settled in Japan where the young aspiring musician pursued studies in music and composition at the University of Tokyo.

Paik moved to Germany to continue his musical education, and there in 1958 he met the American composer John Cage, who became a major influence and occasional collaborator. At the time, Paik was becoming increasingly known in avant-garde circles for his performance pieces, and Cage wrote of an early performance of Étude for Painoforte in Cologne: “Behind Paik as he performed was an open window, floor to ceiling. His actions were such we wouldn’t have been surprised had he thrown himself five floors down to the street. When at the end he left the room through the packed audience, everybody, all of us, sat paralyzed with fear, utterly silent, for what seemed an eternity. No one budged. We were stunned. Finally, the telephone rang. ‘It was Paik,’ Mary Bauermeister said, ‘calling to say the performance is over.’”

Paik’s time in Germany was transformative: in addition to meeting Cage he also met the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen and the artist Joseph Beuys, with whom he would collaborate until Beuys’s death in 1986. In 1961, Paik was invited to join Fluxus by the Neo-Dada movement’s founder, George Maciunas, and it was during this time that he began working with television to create visual presentations of the concepts he had until then expressed through performance. In 1963 he staged his first solo show, at Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany, and it laid the foundation for the radical work that would characterize the rest of his career. Titled "Exposition of Music – Electronic Television," the interdisciplinary display greeted visitors with the severed head of a freshly killed ox, then surrounded them with glowing TV sets, record players, audio tape players, prepared pianos, and other automated media.

While groundbreaking in Paik’s career, the move to video and television was not yet considered to be the young artist’s calling card—or his means of acceptance. As Paik scholar and curator, John Hanhardt notes, “Although Cage, Beuys, and other accepted his video work, Paik’s ‘actions’ and performances were the key to sustaining his place in the late 1950s and early 1960s avant-garde art world.”

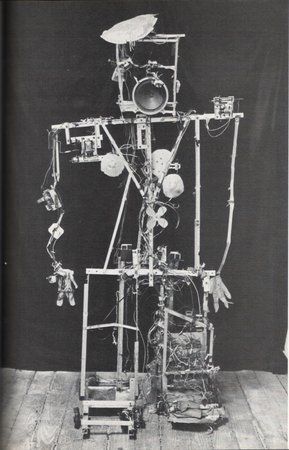

ROBOTS Robot K-456 (1964)

Robot K-456 (1964)

Returning to Japan, Paik delved further into video and electronics. According to Paik’s nephew Ken Paik Hakuta (who today serves as executor of his estate), the artist began working with a Sony Port-a-Pak, the first commercial video recorder, as early as 1962-63—well before it came on the market, thanks to Paik's friendship with a Sony executive. “Sony in those days was still an innovative company interested in giving access to its products to leading artists,” according to Hakuta. On a trip to New York in 1965, Paik famously used the Port-a-Pak to film the Pope going to the United Nations and showed his recording at Cage Au Go Go in Greenwich Village later that day.

While in Japan, Paik also met electronics engineer Shuya Abe, with whom he would go on to create such things as the Color T.V. Synthesizer. For their debut project together in 1964 they created Paik’s first robot work, Robot K-456, named after a Mozart piano concerto. Robot K-456 could walk when prompted by remote, play JFK's inaugural speech, and, humorously, defecate beans—but while technologically advanced, the robot was unabashedly handmade and lurching. Paik didn't want it to work “too well,” according to Hakuta, and there was no attempt to hide its cables and electronic innards. Its most humanlike elements were homespun, even tender: cups from Paik’s sister’s bra and floppy, cut-out hands.

When the robot was included in Paik's landmark 1982 Whitney retrospective, Paik brought it out into the street for a performance. As it crossed Madison and 75th Street, the artist William Anastasi, in a choreographed moved, hit it with a car. After much fanfare, the mangled remains of Robot K-456 were carried back to the Whitney. According to the exhibition's curator, John Hanhardt, “The street performance demonstrated that Paik did not see his artworks as inert and complete but rather as objects that could be remade and refashioned in new forms.”

CHARLOTTE MOORMAN TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969)

TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969)

Encouraged by George Maciunas, who had invited him to “participate in Fluxus actions,” Paik had moved to New York in 1964, where he met Charlotte Moorman, who became one of his most important collaborators from the late '60s until her death in 1991. A Juilliard-trained cellist, Moorman came into Paik's orbit when he visited the first annual festival of avant-garde art, which she had organized. Paik’s collaborations with Moorman were his most effective—and iconic—gestures toward humanizing technology.

For Paik’s Opera Sextronique (1967), Moorman played her cello topless (and was arrested for public indecency). In 1969, Moorman played her cello while wearing his TV Bra for Living Sculpture, which consisted of small televisions harnessed over her breasts that could play video, show closed-circuit or broadcast TV, or modulate to the sound of Moorman’s playing. The piece was not intended to be gimmicky, but rather highly sensitive. As Paik explained [sic throughout], “By using TV as bra… the most intimate belonging of human being, we will demonstrate the human use of technology, and also stimulate viewers NOT for something mean but stimulate their phantasy to look for the new, imaginative and humanistic ways of using our technology.” The TV Bra weighed 60 pounds and Moorman tasked the then-teenage Ken Hakuta with helping her remove it during breaks in the performance—which infuriated Paik when found out. (Ken told his uncle he was happy to help.)

Throughout their decades of collaboration, Moorman played various forms of cello, including: Paik’s TV Cello (1971), a felt cello created with Joseph Beuys, and even Paik's bare back, for a composition by Cage entitled Charlotte Moorman with Human Cello.

TV TAKEOVERS Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984)

Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984)

Paik began experimenting with television programming—“installations,” he termed them—for the masses as early as the 1970s. His 1973 transmission Global Groove commenced with a prophecy: “This is a glimpse of the video landscape of tomorrow, when you will be able to switch to any TV station on the earth, and TV Guide will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book.” He called Global Groove “participation T.V.”

Another major event was Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, Paik’s jubilant response to George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four and its warnings of technology’s domination and an omniscient Big Brother. The hourlong program was broadcast live internationally on New Year's Day, 1984, to an audience of some 25 million viewers via satellite from San Francisco, New York, and the Centre Pompoidou in Paris. As host, the journalist George Plimpton primed viewers, saying, “What you’re about to see are positive and interactive uses of media.” Here's some of what unfolded: Laurie Anderson and Peter Gabriel sang and stared into the camera; French crooner Yves Montand sang; John Cage used a feather to play the needles of a dried cactus equipped with an amplifier; Merce Cunningham danced with a hologram of himself; Allen Ginsberg sang about meditation and disarmament; Moorman played the T.V. Cello, with a little help from Plimpton, while encouraging viewers in her Arkansas lilt, “You could make one at home!” Paik called the broadcast a “global disco.”

Global Groove and Good Morning Mr. Orwell were both shown in the ramp along the rotunda of the Guggenheim during Paik's 2000 retrospective there (also curated by John Hanhardt). Filling the multistoried center of the rotunda was a laser-and-waterfall work called Modulation in Sync (2000). According to Hanhardt, Paik saw the Guggenheim show as a “‘post-video’ project, in which the expanded use of lasers embodied the metaphysical transformation of late twentieth-century technology into energy fields of multiple circuits, interfaces, and connections.”

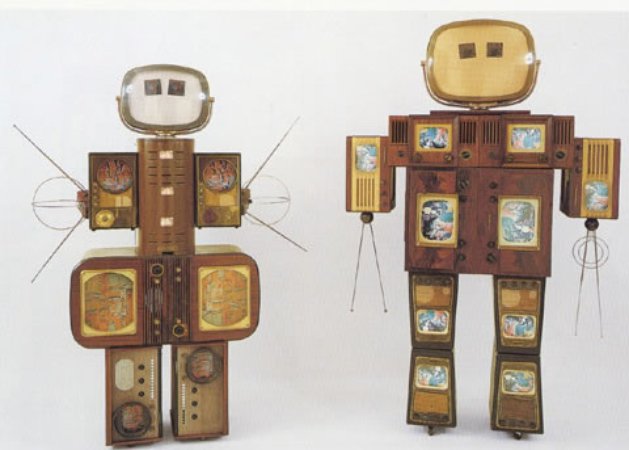

A FAMILY AFFAIR Family of Robot: Mother and Father (1986)

Family of Robot: Mother and Father (1986)

In addition to his populist international video “installations” and technological forays, Paik continued to make sculpture. One 1986 body of work, Family of Robot, incorporated the artist's affinity for family into his experiments with technology. He constructed “family members”—parents, children, grandparents, and eventually extended family—out of television sets, denoting each member not only by their different sizes and but also by the modernity of their components. Family of Robot: Baby, for instance, was made of the latest in miniature TV models, while Family of Robot: Grandmother and Grandfather are made of old, bulky, wood-encased sets. Typical of his oeuvre, the series expressed Paik’s joy in technology and futuristic innovation while remaining grounded playfully, yet attentively, in humanity.