In 1932, when most important art exhibitions in America were conservative affairs administered by academic judges, the one-year-old Whitney Museum unveiled an alternative aimed at leveling the ground to survey the more unruly range of the day's visual expression. “No juries, no prizes” sounded the rallying call for what was then to be an annual exhibition. Artworks hung in the museum's Eighth Street townhouse were not to be treated as entrants in a “beauty contest.” Another radical distinction? Artists selected their own work for the show.

Since that auspicious debut, the show today renowned as the Whitney Biennial went through a number of dramatic transformations—and earned the reputation as being the country's most consistently provocative and opinion-changing display of contemporary art. Some core elements have changed (the Biennial’s $100,000 Bucksbaum Award, established in 2000, is one of the biggest prizes in the visual arts), others have remained the same. Here is a breakdown of some of the landmark moments in the exhibition's action-packed history.

The 1930s and 1940s

By 1937, the show was a success, and the museum quickened its pace, putting on two surveys a year: one in the fall for painting and another of sculpture in the spring. This gave ample opportunities for the insurgent strains of Modernism to seep in. One critic complained that the show in 1944 was “overrun by various brands of fantasy,” eschewing factual representation. Indeed, Whitney darlings included painters Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Sheeler, and Raphael Soyer, who all featured in several dozens of the exhibitions. The “overwhelmingly modernist” sensibility was also exemplified by Jackson Pollock’s 1946 debut.

The 1950s and 1960s

In 1959, the exhibition’s rate slowed to one show per year that alternated between painting and sculpture. Critics began using these events as an opportunity to take the pulse of American art, pronouncing its health robust or anemic, with the more gleeful pronouncements falling into the latter category. By the late 1960s, however, critics turned from blaming the state of American painting for various sins to blaming the Whitney’s approach of letting in as wide an array of artists as possible—there were calls for the annuals to be more tightly curated. In 1969, then Whitney director John I. H. Baur agreed, declaring that it was no longer possible to “approximate a cross section of the creative trends of the moment” in any objective way. Curators, as a result, began to craft their presentations along descrete themes.

The 1970s

In 1973, the museum condensed the shows into one mega-biennial every other year, the format we now know. (Note, this rhythm will be disturbed with the Whitney’s 2015 decampment downtown; the next Biennial won’t be until 2017.) In this first official Biennial, over 220 artists filled the five floors of the Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue, including Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Joan Mitchell, Robert Motherwell, as well as younger artits like Barbara Kruger, Louise Fishman, and Peter Campus. In addition to the outsized number of artists, the installations were also bigger, and sometimes bombastic. On the Museum's pedestrian bridge, for instance, Rafael Ferrer built a teepee called Fuegian House With Harpy Eagle.

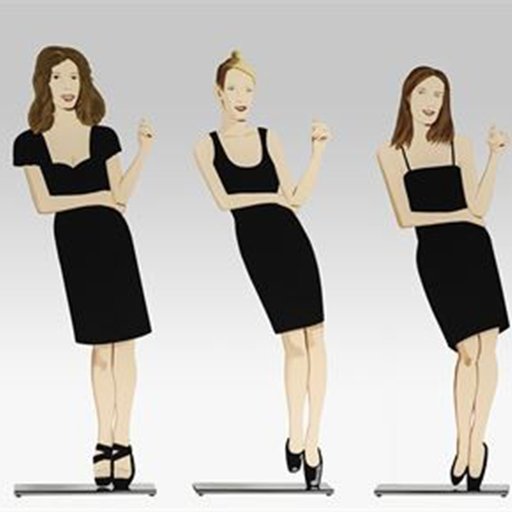

But anxiety over the influence of the art market upended the 1975 Biennial, where curators reacted by only selected artists who had never exhibited at the Whitney and hadn’t had a New York show in the past 10 years. One Art in America writer dubbed it “The Virgins’ Show,” and critics lambasted it. Apparently, there were many bad Brice Marden imitations. Remedying the offense, the 1977 Biennial included artists with sizable reputations, among them: Minimalists Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and Richard Serra, and the photorealists Chuck Close and Richard Estes. Following, the 1979 show somewhat balanced the male-female ratio—a continual target of critique during the shows—by raising the number of women participants to a third. It also evened out the roster generationally. Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, and Philip Pearlstein were placed next to newbies like Martin Puryear and Susan Rothenberg.

The 1980s

The 1981 show emphasized trends in painting, as well as introduced new talents like Robert Mapplethorpe, Robert Wilson, and Julian Schnabel. In the following edition, the exhibition's pillars were Neo-Expressionism and figurative painting; it was also the first multimedia Biennial, with film and video. Robert Hughes, a critic known to be less than kind to artists who still walked the Earth, complained in Time magazine that the subsequent 1985 Biennial was the “worst in living memory,” because of its focus on East Village artists, such as David Wojnarowicz, Kenny Scharf, Tom Otterness, and Rodney Alan Greenblat.

In 1987, 24 percent of the artists were women in the show, prompting the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous group of feminist artists, to stage “The Guerrilla Girls Review the Whitney” downtown at the Clocktower, displaying graphs and charts of women and minorities in biennials since 1973. The Biennial attempted to correct its oversights in the next iteration—40 percent of the artists were female.

The 1990s

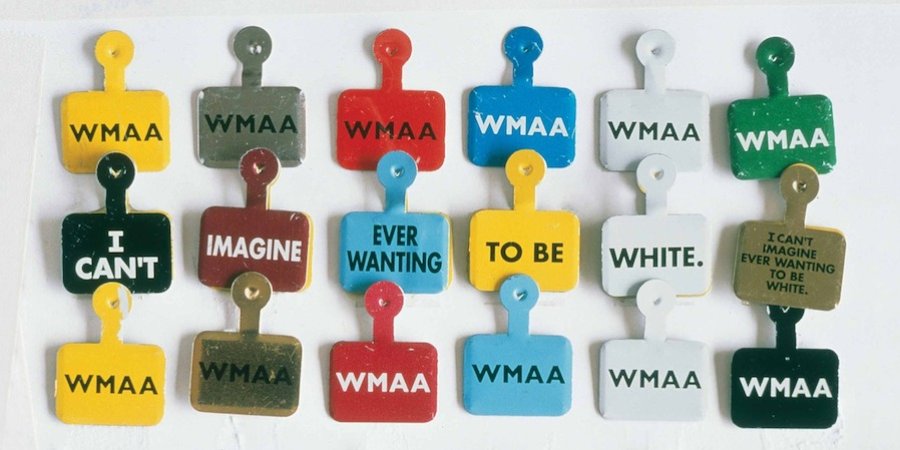

Dividing the floors by generations, the 1991 Biennial took on a more aggressive, edgy look, addressing themes of the times: AIDS, sexuality, and race. But this was merely a harbinger of things to come. The 1993 show—the “political one”—curated by Elisabeth Sussman, was heavy on social theory and light on beauty. Upon entering, visitors met Pat Ward William’s photomural of five black youths, graffitied with the words: “What you lookn at.” They received museum tags designed by the artist Daniel Joseph Martinez that read "I can't imagine ever wanting to be white." Women and gay artists had a strong showings, and there was provocative body art by Janine Antoni and Matthew Barney, a domestic scene installed by Pepón Osorio, and a film about lesbian lovers by Sadie Benning.

The show was “less about the art of our time than about the times themselves,” as Roberta Smith wrote in the New York Times. In the same newspaper, the critic Michael Kimmelman had a less nuanced take: "I hate the show." The Biennial has since been recognized as one of the more prescient and consciousness-expanding in the exhibition's history.

The tenor of the following 1995 Biennial was far lower-key, favoring sensorial art over the social. Curator Klaus Kertess unpretentiously championed neglected older generation of artists, folk artists, and outside artists, like the deaf artist Joseph Grigeley, who displayed a gird of scribbled notes he used for communication. Paying attention to the scene outside of New York, Kertess also included Canadian artists Jeff Wall and Stan Douglas.

The 2000s

After a series of administrative departures at the Whitney in 1998, a team of outside curators organized the 2000 show, which critics skewered as diffuse and lacking a point of view. In 2002, curator Lawrence R. Rinder said he worked “without concern for the art market or art world accolades.” But the effect was again mild-mannered, though he did incorporate more outside artists and artists living away from the anointed art capitals. Only a quarter of the participants, however, were female.

Critics celebrated the 2004 edition as the best in memory. Curated by the Whitney’s Chrissie Iles, Debra Singer and Shamim M. Momin, the show placed a Paul McCarthyblowup balloon atop the Cyclops building on Madison, and the Internet-age interest in materiality heralded the return of painting and drawing, with showings from David Hockney, Elizabeth Peyton, Julie Mehretu, Laura Owens, Amy Sillman, Laylah Ali, Cecily Brown, and James Siena.

The 2006 Biennial, as signaled by the fact that it was titled “Day for Night," was more of a thematic exhibition than survey. European-born, Whitney-native curators Chrissie Iles and Philippe Berge organized the show and, in one section, traced the influence of Europeans like Martin Kippenberger and Thomas Schütte on a young American sculptors.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the Whitney Biennial tightened its belt—the 2010 show half the size of the 2006. Titled “2010,” it treated the Biennial as a clock that marked a moment in time. Historically oriented, it also devoted an entire floor to past occasions in the Biennial’s history.

The latest 2012 edition placed artists at the heart of the event. Organized by Whitney’s photography curator Elisabeth Sussman and then-independent curator Jay Sanders, it elevated the act of curating as an art itself, inviting artists to organize mini-shows within the ur-exhibition. Critics hailed it as a signal achievement, with the New Yorker's Peter Schjeldahl calling it "among the best ever" in the Biennial's history.

What will the lasting legacy of this year's edition be? Only time will tell.

READ THE REST OF OUR WHITNEY BIENNIAL COVERAGE

Curator Michelle Grabner On Her Unruly "Curriculum"

Curator Stuart Comer On His Shapeshifting Presentation

Curator Anthony Elms On The Rise Of Literary Art And The Usefulness Of Ghosts

Artist Amy Sillman On Painting, Stand-Up Comedy, And Making Inappropriate Art

5 Ways Of Looking At The 2014 Whitney Biennial