In 1989, scavenging through a Brooklyn junkyard, James Siena retrieved two quarter-inch-thick aluminum panels, whose proportions reminded him of the loose-leaf paper he doodled on as a boy. Ever since the scrapyard romp, the American artist has painted his abstract geometries on metal tablets like these. He’s also made an indelible mark in the New York art scene, earning representation with Pace Gallery and placing his rigorous, rule-based works in the collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney, and the Museum of Modern Art.

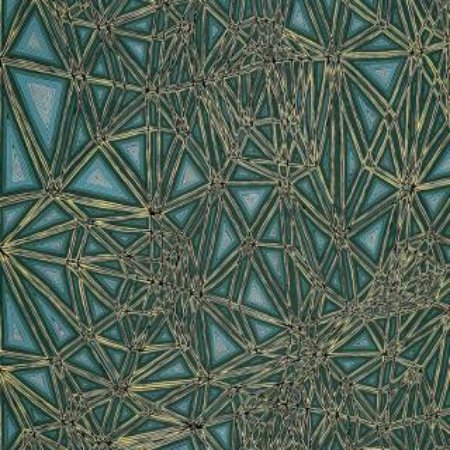

It’s fitting that Siena discovered the panels among the scraps of industry, as he calls his paintings “two-dimensional machines.” With a set of predetermined rules in mind, he executes the compact, self-contained circuits in sign-painter’s enamel paint. But the process is not rote, nor the results affectless. He often lays out these intricate systems only to then distort them to surprising effect. “The assumptions that viewers make when they first look at a picture,” Siena says, “are contradicted by direct examination.”

In this way, the visual matrixes resemble the urban grid of New York City, where Siena has lived since 1982. Life here erupts from the austere, ordered streets—on this February afternoon, outside Siena’s studio on the Lower East Side, Chinese New Year firecracker debris and colorful confetti spangle the icy roads. His systemized paintings capture a similar phenomenon, snapping to life at irregular intersections and through violations of the rules.

Inside Siena’s two-room studio, a calm order pervades. Rows of antique typewriters and dusty boxes of papers line one wall, and a bicycle hangs immobilized from the ceiling. In the next room, paintings perch on a shelf and stack along the floor. He is “policing them,” he says, letting his eye make passes over the nearly-finished surfaces to catch any visual snags: wavering lines, irregular marks. Even the act of looking, for Siena, is disciplined.

After graduating from Cornell University with a degree in fine art, Siena supported himself partly by cutting mats. You see the regimentation and level of precision requisite to that job not only in his current practice, but also in his day-to-day life. He wakes at the same hour every morning and packs a simple lunch of salad with bread and cheese to bring to the studio from home. He rotates through five pairs of pants, all the same color. And at age 56, he still runs five days a week, clocking an impressive 7-minute-45-second mile.

But inevitably, life happens, and routines are jolted. In November 2012, that disturbance came in the form of a distracted cyclist, whose bike flung Siena, on a run, hands first into the macadam of the Brooklyn Bridge. A sinister contusion spread; he had broken the wrist of his painting hand. After months of physical therapy, his bone healed, and he has since dedicated a painting of interlocking puzzle-like pieces to the doctor who saved his hand, and his artistic practice. As we sit down to talk, he begins to detail the accident, but, like a line in one of his paintings, the conversation goes somewhere altogether unexpected.

Edited from an interview with James Siena

I like to graphically describe my injuries. Oh, you're squeamish? Then never mind. Maybe that is part of my personality to like to meticulously… obsessively… well, people call me obsessive, but I hate the word. I just think I’m intense. There’s a difference. Kusama is obsessive, and I love her to death. But I’m no Kusama.

In my work, I’m not thinking about patterns—I don’t like that word. The boundaries of my paintings are very important, and often times part of the composition. There’s a little early Stellain that, but there is also this idea of compression that I don’t think I consciously stole from anybody. The intensity of a small picture has always appealed to me.

So, yes, while my work is detailed and intricate, it's more derived from thinking about machines. A bicycle accelerates our speed and a typewriter accelerates our thoughts. It's an advanced form of tool use. But there is another way to talk about that. I could say that I’m interested in the machinery of seeing, or the machinery of thinking. I mean, other people have said that my works “think”—that they are like circuit boards or passages.

When I prepare to begin a new work, sometimes I refer to a box of what I call "thumbnail drawings." Do you want to see them? Each drawing is a kind of schematic, like a shorthand notation that I can follow. But when I execute a painting using that modality, the density and complexity can be highly increased. I’m not just going to scale up the mark.

Well, I have made so many of these thumbnail drawings now that I have them in my head, you know? Now I usually start a painting with a sharpie. You can see one right there. I got the yellow paint out and I'm going to follow my lines. When I begin with drawn lines and then paint them in enamel, you can think of the works as "paintings of drawings."

I go in with some rules. They are always unwritten, but I write them down afterwards sometimes, for writers on my work. Generally, it’s all free-hand. I like slippage. Yes, of course, the rules are adapted or distorted. I love late Sol LeWitt, where his grids appear to sag under the weight of gravity. Sometimes I put infections on intersections too, where the lines cross as if some mold or something has grown there.

LeWitt is definitely an influence. There is both the more cerebral, Apollonian side of LeWitt, but he also lets in the Dionysian. Behind every abstraction is a human being. He might make an instruction for a drawing on a wall that says, “one thousand lines, four inches long, crooked.”

It's the “crooked” that makes that human. Because the hand of the person making the crooked lines is going to be different every time. It is the responsibility of the viewer to respond to the humanity of the artist no matter what, because it’s always there.