The star curator Massimiliano Gioni is known for opening up hidden worlds and alternative histories, but in one respect his shows are surprisingly traditional: they include rich concentrations of eerily realistic figurative sculpture. The genre was unavoidable in Gioni's 1990s-themed surveys "Ostalgia" and "NYC 1993" and in last year's solo of the sculptor Pawel Althamer, to name a few recent examples from the New Museum, where Gioni is associate director and director of exhibitions. It's also omnipresent in his current show “The Great Mother” at Milan’s Palazzo Reale (through November 15), a sweeping overview of maternal imagery in 20th-century art produced for the Expo in Città 2015 under the auspices of the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi.

On the occasion of "The Great Mother" and Phaidon's new book Body of Art, Artspace's Karen Rosenberg spoke to Gioni about the enduring appeal of figurative sculpture, his influences from Catholic church statues to Mike Kelley, and why he thinks this art form is especially vital today.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Artand buy the book.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about a resurgence of the figure in contemporary sculpture. Some of the most high-profile pieces in the New Museum’s Triennial last spring were figurative sculptures, and now a large gallery in MoMA P.S. 1’s “Greater New York” is dedicated to the genre. Why do you think the body is coming back into sculpture?

I don’t know if it’s coming back—for me, art has been about bodies looking at bodies from approximately 35,000 years ago until today. From the beginning of time, we have made sculptures and objects to represent each other and to represent people whom we’re about to lose. The Romans made death masks to preserve the images of people they loved. It’s not so much that there is a return to figuration, it’s just that figuration is the territory in which many of the fundamental preoccupations of art are expressed.

That’s true. But many artists are making a kind of figurative sculpture that feels new and transgressive, even though they’re using forms and techniques associated with academic realism. I’m talking about Charles Ray, Paul McCarthy, Maurizio Cattelan, Robert Gober, and Jeff Koons, among others. You’ve exhibited all of those artists; can you explain what makes them look so contemporary?

I think it’s most obvious in the work of Ray, an artist who’s looking at a whole tradition that goes back to Greek sculpture, but who works with new materials and in a way that makes his sculpture look Martian, otherworldly.

That’s another reason for my physical fascination with a certain type of figurative sculpture. There is a sensation which Freud called the “uncanny” and Mike Kelley explored in his famous exhibition of the same title, the feeling of being faced with certain sculptures that occupy the same space as us and yet somehow feel completely from another dimension. That’s what makes some of this contemporary figurative sculpture so interesting—it foregrounds this experience of inhabiting our own space and at the same time offers access to another space and time. Kelley’s exhibition was a big influence on me, both as a curator and an art lover.

What was it about “The Uncanny,” the show-within-a-show that Kelley organized for the Sonsbeek '93 exhibition in the Netherlands, that had such a profound effect on you?

It was an exhibition of figurative sculpture, and particularly polychrome, hyperrealistic sculpture. Much of my taste has been formed by those objects—and maybe also because as a young Italian Catholic, I was used to seeing sculpture as polychrome and extremely realistic.

Figurative sculpture of that type is also particularly interesting to me because it’s not just meant to be contemplated. It’s meant to be felt and to have an effect on the viewer. Think of the thousands of crucifixes and Pietàs in Italian churches—those are sculptures that are meant to have a specific effect. We think of the history of art as the history of forms and styles—very seldom do we think of it as the history of pictures that do something to people.

There’s a beautiful book by David Friedberg called The Power of Images that looks at the history of art as the history of images that do something to people. He looks at pornographic images; he looks at sacred images that are meant to facilitate a reaction in the church. Figurative sculpture makes this transitive effect of art more explicit. It’s not just meant to be looked at and contemplated rationally.

That transitive power of figurative sculpture has sometimes been a liability. Historically, or in literature at least, very realistic sculptures of the female body have tended to elicit erotic responses. Think of the Pygmalion myth, or the Aphrodite by Praxiteles.

What you are saying immediately makes me think of cultures that don’t allow representations of bodies. There are many throughout art history, and they are not necessarily associated with certain religious agendas. You mentioned the myth of Pygmalion, and there are many other myths. They confirm something magical in the art of representing people.

On the other hand, figurative sculpture is by definition populist. I always think it’s quite significant that one of the most attended shows of the recent past was the “Bodies” exhibition [of preserved human cadavers], which says a lot about our taste. Irony aside, figurative sculpture is to a certain extent not recognized intellectually—it is deemed too popular, too basic. That’s what makes it more interesting to me. It’s not only the context in which art was invented, and the place where we negotiate death and missing people, but it’s also a form that’s open and popular. It can bring together Bernini and the “Bodies” exhibition. There’s an inclusiveness that interests and fascinates me.

Do you think technology is also a factor in the reception of these sculptures? Our relationship to space and to the body, to our own bodies, has changed so much in the past few decades.

Maybe looking at these sculptures is a way to compensate for the de-materialized experience that we have every day now. We are so exposed to technology that some of these figurative sculptures become more relevant, because they require a physical experience. Some of the artists you mentioned—a wide spectrum, from Althamer, who works with extremely modest materials, to Koons, who works with the most industrial and sophisticated materials—share this transformative experience of space. You feel your body differently in the face of these figurative sculptures.

I think it’s particularly evident in the work of Ray, because the way his sculptures affect the body of the viewer is quite extraordinary. They make you feel different. It’s an almost therapeutic aspect of figurative sculpture today—it activates a series of muscles, metaphorically and not, which have been weakened by our daily experience.

So you think that figurative sculptures serve a different purpose today than ancient figurative sculpture did in its own time?

Probably, yes. They make us come to terms with physicality, in a way that in ancient times and probably even in the 1970s was not the same. If I think of the ‘70s, it was less of a figurative time—I can think of bodies in videos, but not in sculptures.

Let’s talk a bit about “The Great Mother.” How did you choose to focus on the mother figure, as a way of telling the story of 20th-century art?

The theme of the Expo was nutrition, and I was trying to find a theme that was somehow related to the topic but also would allow me to go more into depth. An exhibition about motherhood emerged from the idea of nourishment and primordial food. It’s about looking at the 20th century from a different perspective, through a theme that is intimately connected to the history of art.

The very first human-made object is a depiction of a woman, and a woman who’s probably pregnant—the famous Venus of Willendorf sculpture. From the very beginning, the illustration of maternity and art are entangled.

How did you bring this ancient image of the fertility figure into a show of 20th-century sculpture?

It’s not so much an update—it’s a survey of representations of mother’s bodies and women’s bodies. The starting point of the exhibition is Freud’s “Interpretation of Dreams” and the work of the Jung collaborator Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn, who amassed a gigantic archive of more than 350 images of women-goddesses.

Then the exhibition moves on to look at the way in which avant-garde movements such as Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism dealt with the representation of women and the representation of mothers. Some interesting things emerge: movements we always imagine as progressive are revealed as extremely misogynist and built on 19th-century values.

The last part of the show, which starts off with Louise Bourgeois, looks at how feminist art has both embraced and criticized certain representations of motherhood, and how it’s often gone back to myths of goddesses and mother figures to reappropriate power.

What are some pivotal examples of figurative sculpture from the show?

One thing I enjoy is looking at objects that might not be read as figurative or illustrative, but change our perspective so that they do. For example, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain doesn’t appear to be figurative. But at the time of its realization, it was described as “a Madonna of the bathroom.” When you put it in the context of this exhibition, suddenly it looks like a womb with a strange digestive or reproductive tube sticking out of it. The exhibition is full of examples of this switch in perspective.

A central figure in the show is Bourgeois; she connects to both Surrealism and Paleolithic sculpture, and she imagines an anti-patriarchal form of art. One of her most famous pieces is called The Destruction of the Father, and the collection of her writing has the same title. She’s also an artist for whom abstraction and figuration become two ends of the same spectrum.

It’s difficult to think of major female artists since the 1970s who work with figurative sculpture in the way of a Charles Ray or a Paul McCarthy, although I can think of many celebrated female artists who have used the body in installation and performance art. Why do you think that is?

It’s a big question—again, it goes back to the Venus of Willendorf. Adrienne Rich, who wrote this beautiful book Of Women Born, which was one of the books that kept me company as I was preparing “The Great Mother,” says that we have evidence that the pregnant woman was at the center of some sacred belief—she was recognized for her power. But she also says that have no idea whether those representations were made by men or by women, and that is a crucial question. We do know that, for centuries after, it was mostly men making these representations.

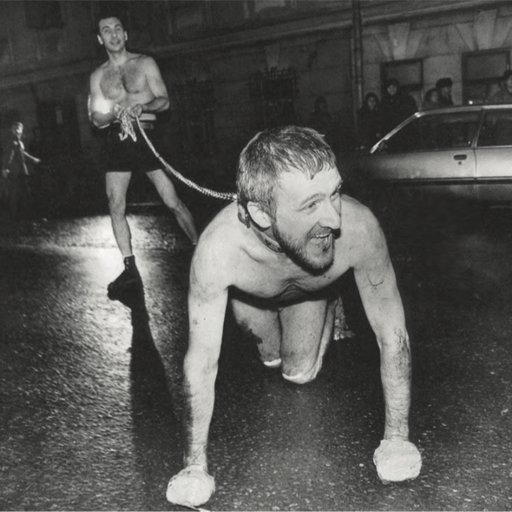

I think that at one point in the recent history of contemporary art, women artists decided to represent their bodies in ways that differ radically from the representations that preceded them. A lot of feminist work is body-centric through performance. In the 1970s, the more militant or political feminist artists decided that it was time to bypass the problem of representation—they refused to be represented, and they presented themselves in the flesh.

Like “The Great Mother,” Body of Art takes a wide-angle view of art history; the Venus of Willendorf is there, and so is Joan Jonas’s Mirror Check. What are some of the challenges of assembling this kind of survey?

Great art is about making us understand how we live and exist in our own bodies, and this show lent itself to understanding that the representation of bodies is often political. I don’t mean to say this critically, but it’s a criticism that is often addressed to my shows: Whenever we look at the body, it’s easy to think of it as universal. What we have learned from feminist and postmodernist thinking is that every body is a cultural construction. There’s no such thing as a “universal” body. When people look at figurative sculptures they tend to fall for that assumption.

Having a non-chronological structure can also be dangerous. If we make books or shows to prove that everything is the same, we're in trouble. But if we make them to stress the differences, through juxtapositions, that’s when things start getting interesting.