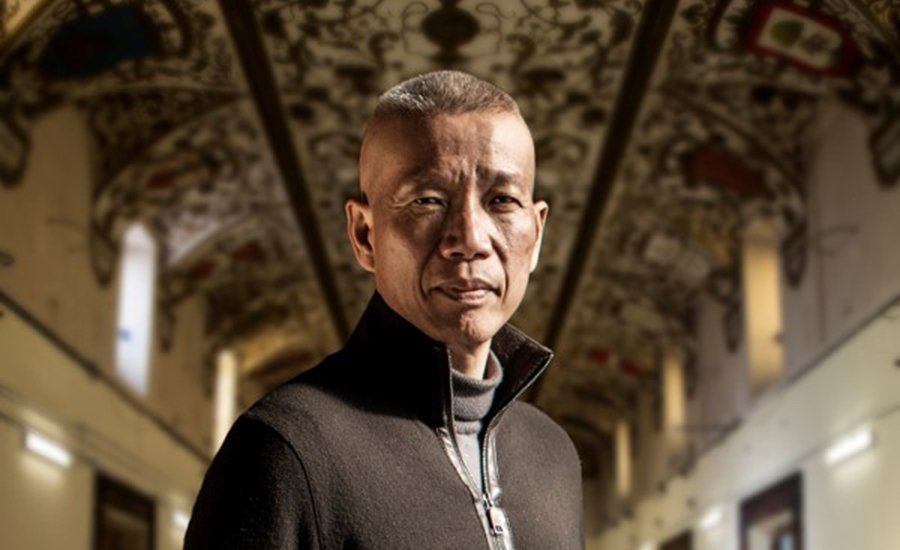

This past fall was landmark season for the career of Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang. In addition to solo exhibitions at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and the Prado Museum in Madrid, Guo-Qiang staged a public art project in Philadelphia in September called Fireflies, in which 27 pedicabs adorned with 900 colorful lanterns drove along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway at night, shepherding members of the public from Logan Square to Iroquois Park. If somehow you missed the everywhere, all-the-time season of Guo-Qiang, you’ve probably seen the gorgeous documentary about him and his work, Skyladder, on Netflix. (If if not, it's a must see!)

Hailed as one of the most significant Chinese artists who emerged in the 1990s, Cai Guo-Qiang’s explosive work uses a diverse array of media, the most renowned being gunpowder. His use of the material, like much of his art, draws on both his Chinese heritage while also conjuring up Western conceptions of the Universe (like the Big Bang). Born in China in 1957, Guo-Qiang largely established his artistic career in Japan where he lived from 1986 until 1995, when he moved to New York (where he lives today). Because his art is often site specific, his work is largely influenced by the surrounding culture, so Guo-Qiang's move from East to West brought a significant change to the artist's work and perspective.

In an interview with New York-based curator Octavio Zaya from the artist’s monograph published by Phaidon in 2002, we revisit Guo-Qiang’s complex relationship to art and nation during a time when borders and multiculturalism is a topic of divisive political debate.

Mushroom Cloud (1999). Image via the artist.

Mushroom Cloud (1999). Image via the artist.

We met in 1995, when you were about to leave Japan and move to the United States. Did you have any expectations when you arrived in the States?

Not really. My biography at that point was of a Chinese person active as an artist for many years in Japan and who had also worked a bit in Europe. It was clear to me that the twentieth century is the American century; I thought it would be a good place to stay and live for a while. The contemporary art system is so different here in the States; everything is different, from the exhibitions to the institutions, galleries, collectors, and media. Art is like an industry over here. It’s like the official army, whereas in China, art is like the underground guerilla forces and in Japan it’s more like the militia. In Japan I could work with people on the streets who would help with the projects, I could motivate ordinary people to work with me. Here it’s different, everything is so professional. If you want to hang something on a wall you have to have a license. Everything has to be done “professionally,” and this has probably caused a shift in my work. There are fewer grass-roots projects. And because of the language barrier and cultural differences, I tend to focus more on visual impact. Besides, as my concern for the universe decreases, the cultural and humanistic concerns in my work have increased. Some critics have noted that I’ve retuned from the heavens back to earth.

The first work you made when you arrived in the States was a series of photographs, Century with Mushroom Clouds: Project for the 20th Century (1996). Besides the obvious reference to the atomic bomb, this work opened up a new relationship with reality in your work in terms of a larger awareness of political and social issues. I can trace this same concern in the most important works that you produced in the following years, such as Cry Dragon/ Cry Wolf: The Ark of Genghis Khan (1996) and Borrowing Your Enemy’s Arrows (1998).

The I Ching, as suggested by its translated title The Book of Changes, is about theories of change. The Chinese ideogram for I literally means change, and this pertains to everything in the universe. I am no different. When I’m in a new situation my methods and concerns change with that environment; the work Century with Mushroom Clouds reflects this shift when I moved to America. I felt that the mushroom cloud was one of the most important symbols of the twentieth century. After the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, military use of nuclear technology continued in the form of a “deterrent” or threat. In a sense the mushroom cloud became increasingly conceptual, rather than real, as time went on. It becomes like the Great Wall of China because, practically speaking, the Wall doesn’t really keep the enemy out. Once you climb over the wall, no matter how long it is, you’ve gotten across. But strategically and politically it’s extremely important to have this thing there. Displaying power, imposing power, is extremely important. For the first “mushroom cloud” explosions I made when I came to the States, I used the cardboard tubes inside a roll of fax paper and some gunpowder I bought in Chinatown. These works showed me that it’s really not about physical size, but the precision of one’s perspective and focus.

Then came Cry Dragon/Cry Wolf: The Ark of Genghis Khan, a relatively large-scale work for my first US museum exhibition (“The Hugo Boss Prize 1996,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, SoHo, New York). The work retraced backwards the journey of Marco Polo, the first Westerner to visit the East and return with tales of his travels. Here someone from the East came to the West, like Genghis Khan. At the time of the exhibition the Asian economy was very prosperous and China was just emerging as a new world power. There was some concern expressed by the American media that Asia might take over as the leading world power in the twenty-first century, reflected in the front cover news stories of magazines like Time and Newsweek. Often the dragon was used as a symbol of China and its assertion of power in relation to the West. Of course the title of this work is taken from the story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” using a play on words to suggest it might be a dragon that’s coming instead of the wolf, and that it may arrive when you’re least prepared. Of course the East thought that its time of world dominance had finally arrived, but I felt this assertion was a bit premature, exaggerated and arrogant.

The work was made of 108 sheepskin bags and three Toyota engines, which formed a dragon that rose up from the ground. The engine motors powered the entire floating dragon from behind, giving a sense of threat and excess. The work referred to the symbolic Chinese dragon, using two elements. The first was a reference to the use by Genghis Khan’s soldiers’ of vessels made of sheepskin. Normally they would use these to hold drinking water while travelling, but when they came to a river they would fill the vessels with air and use them as flotation devices. When they were faced with a large river they could very quickly assemble rafts using these air-filled floats. This was how they were able to advance rapidly across vast areas, all the way to Europe and the borders of Egypt. The second element is a later, more modern mode of transportation: the Japanese car, for example, the Toyota, which is a very popular, economical and reliable form of transportation. With the manufacture of these cars the Japanese could penetrate economically into many countries – a different kind of “invasion.”

For the 1997 Venice Biennale I made a work called The Dragon Has Arrived! It was a pagoda that looked like a missile taking off. The pagoda was a reincarnation of the 1994 tower I made in Iwaki, Japan, which was first shown in Returning Light: The Dragon Bone (Keel) in three separate parts. Later, in 1995, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, it was shown stacked together in one piece. This time, the tower took flight; Chinese flags were added to the tail and these looked like the fire of a missile at take off. I often recycle earlier work if the opportunity arises, so that it continuously morphs into new lives.

Another work of that time, Cultural Melting Bath: Project for the 20th Century (1997), which you presented at the Queen’s Museum in New York, was more irresolute, less obvious in its implications.

Cultural Melting Bath: Project for the 20th Century was another work that aroused varying reactions when it was installed differently in Europe, the United States, and Japan. Nine large taihu limestone rocks, used in the traditional Chinese art of gardening, were arranged in the gallery as miniature landscapes, creating a space for the free flow of chi or vital energy. A jacuzzi was placed in the centre of the space, containing water infused with herbs that are beneficial to the bathers’ skin. A large transparent curtain or net separated this work from the rest of the museum. Birds actually lived inside the net, and this resulted in a very strange space for the audience. I first used taihu rocks for a show at the Louisiana Museum of Art, Humlebaek, Denmark for the piece Flying Dragons in the Heavens, 1996. Denmark has a good social welfare system, with a stable society and relatively little social conflict. So, for the show there I leaned towards using aesthetics, rather than politics, as a topic of discussion. The show was about using what is there to reveal what isn’t; in other words, the stones were not the most important element in the work, but rather I highlighted the spaces created by the rocks. The audience is invited to walk amongst the rocks while flying kites. The change in energy flow created by the rocks was perceptible through the way the kites behaved as one walked through the space. This method also related to Chinese traditional painting: when the ink hits the paper with a brushstroke, the dark area doesn’t only convey its own darkness but refers to the contrasting white surround that is also “created.”

When it was to be shown in New York, I felt that the Cultural Melting Bath as it was could not establish a dialogue with the vastly different social realities of American life. Without a dialogue, without some friction with reality and the immediate context, the work would lose its power and spirit. So in this version I added an American jacuzzi. It still looked beautiful, like a traditional Chinese painting, complete with the sound of bubbling water. The work really becomes interesting, however, when you’re in the water taking an herbal bath with a group of people; that’s when the friction occurs and the work has the most resonance. Being in America, bathers had to sign a form to waive the museum of any responsibility, in their health or otherwise, related to the communal bathing. Once in the bath, exhibition visitors found themselves with people of totally different cultures and backgrounds; the work set up a direct relationship with the conditions of living in America. It’s the idea of the cultural melting pot of New York.

When the work went to Japan it took on yet another form. The Japanese love taking hot baths together without the fears of contagion that the Americans have, so the conditions were different yet again. This time I set the piece outside, drawing on Japan’s island relationship to the ocean. The rocks were arranged according to feng shui principles; the site has now become a meeting point for museum staff and locals beyond the use of the jacuzzi. This version of the Cultural Melting Bath returned the work to aesthetics, about traditional Asian ideas in a contemporary setting.

I often feel that I’m in a state of sway, like a pendulum. On one side of the pendulum is my own cultural history and background, as it faces a new era and new challenges. How do we raise new points of departure from within to advance and extend the East? On the other side is my experience in the West; its concerns have become mine and I can’t help but address its dilemmas as well. Sometimes these two sides oppose each other; sometimes they overlap.