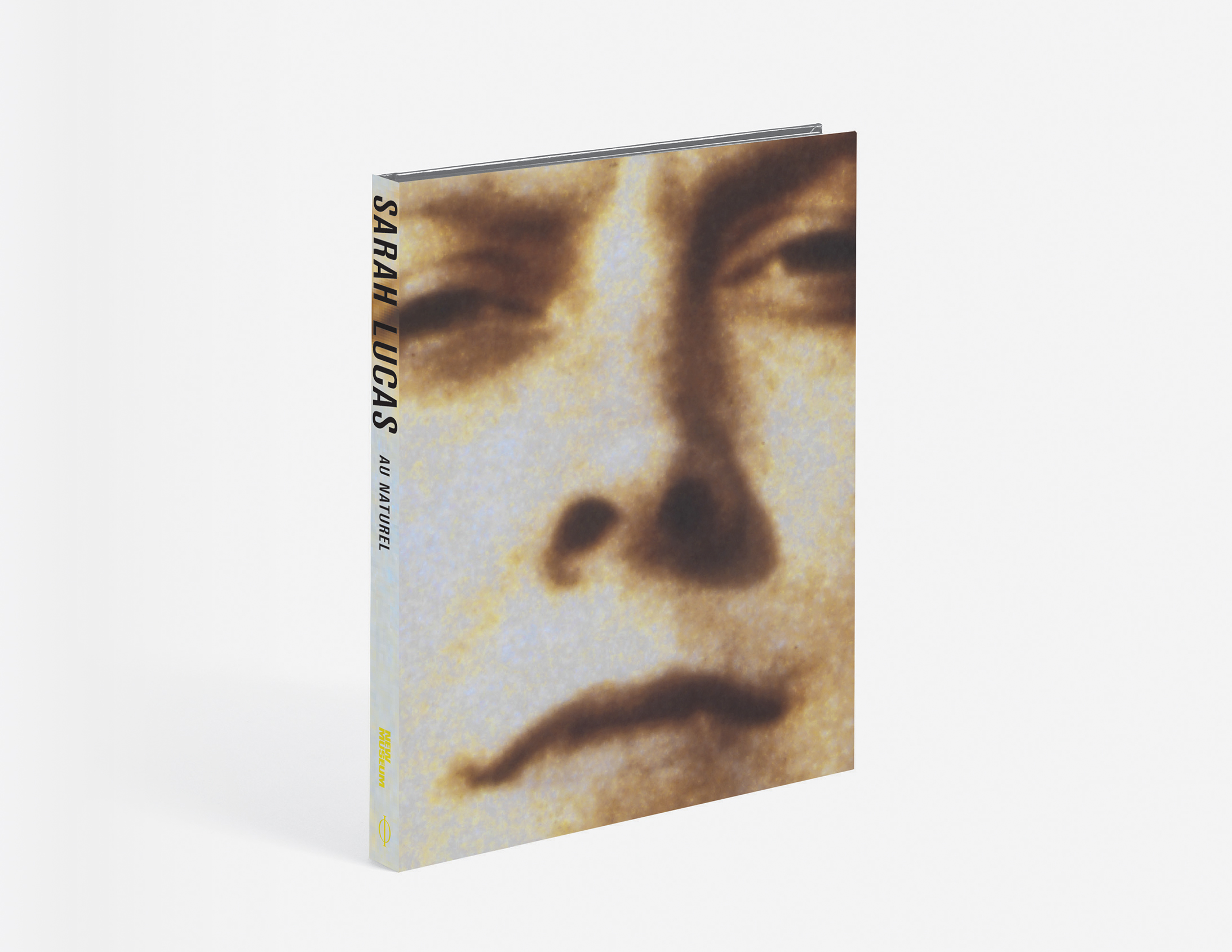

This week is the opening of the New Museum ’s “Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel,” which, surprisingly, is the very first U.S. museum retrospective of one of the most celebrated British artists to come out of the '90s. The exhibition brings together nearly 200 works, across mediums and her career, to reveal the brilliant scope of her art—and us New Yorkers are thrilled about it.

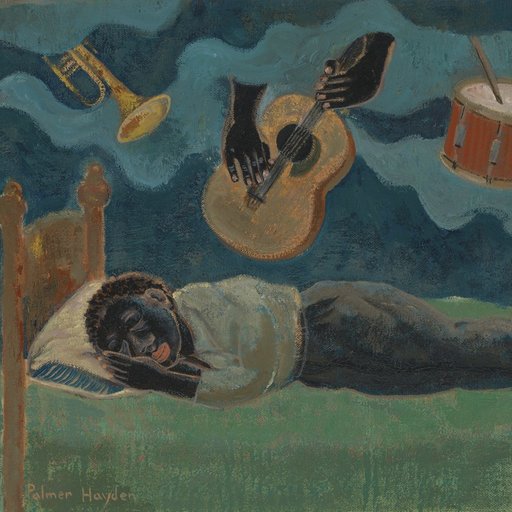

For over 30 years—using a variety of food, furniture, and clothing— Sarah Lucas has made us question cultural standards of femininity; and has made us laugh while doing it. Her art, imbued with her crude sense of humor (typically expected of men), subverts traditional notions of gender, sexuality, and identity. Anthropomorphic figures repeat throughout her work in comical, sexual, or fragmented ways—for example, her early sculptural work from the '90s replaced domestic furniture with human body parts. Also reappearing throughout her art are British tabloids, cigarettes, and toilets—and the way in which she compiles such mundane, found objects transforms them to become charged pieces.

Sarah Lucas,

Au Naturel

, 1994. Mattress, melons, oranges, cucumber, and water bucket, 33 1/8 x 66 1/8 x 57 in (84 x 168.8 x 144.8 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Au Naturel

, 1994. Mattress, melons, oranges, cucumber, and water bucket, 33 1/8 x 66 1/8 x 57 in (84 x 168.8 x 144.8 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

A graduate of London’s Goldsmith’s College, Lucas was originally associated with the Young British Artists (YBA’s) , a group that rose to fame in London in the late '80s and early '90s with the support of influential collector Charles Saatchi. While many perceive the artist to epitomize angsty, DIY grunge, in an interview with New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni (excerpted from Phaidon’s new catalog of the retrospective) Lucas reveals, "I am really not grungy at all." Read about how the artist's aesthetic and process came not from a conscious effort to assimilate with "grunge" culture, but from a lack of financial means and studio space; about the first few shows she ever had; and about the reception of her provocative work.

Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel

is available on Arspace for $79

Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel

is available on Arspace for $79

Do you think the abrasive quality of your work—the sense of anger that I see in some of your early works, like the cement boots or the shoes with the razor blades—came out of that conflictual relationship between political and social work and mainstream culture? Was art a tool of confrontation for you?

It’s a tricky thing, and I don’t know how angry I was, but I’ve certainly gotten that reputation. In those days, I had no money whatsoever: I had to go everywhere either by foot or by bicycle. I was walking across half of London sometimes. I’d go to a party and have to walk back on my own, and London was a much scarier place at that time. Just to walk around in some areas you had to be a bit tough. I think it was a practicality as much as anything else, because you have to protect yourself.

Would you say that it was at Goldsmiths that you realized you were going to be an artist?

I don’t think so, actually. I had already been out of Goldsmiths for a year when the “Freeze” show happened in 1988. Being at Goldsmiths was kind of brilliant because it had no syllabus and hardly any academic requirements. If you wanted to speak to a tutor, you made an appointment with them to have a chat, but it was very informal. I wasn’t the person that went in for the most teaching in the world, but there were good teachers—notably, for me, Richard Wentworth and Michael Craig-Martin . Many others. It was a good mix. Goldsmiths was also very social and I got to know people who had left the school three years before, and people who had come up behind me. It was like a proper organism, and, in that way, it mirrors what real life is like or what the real art world is like. After the “Freeze” show, I remember thinking, “Oh, I’m just going to stop doing this,” mainly because I got so fed up with investing in a load of materials—bricks or blue shiny plastic, or whatever it might be—and filling up my whole room with it, and nobody being interested in it. I thought, “I’m just cluttering myself up here,” and I hate clutter. After “Freeze,” when galleries were sniffing around various friends of mine, I started to realize that, OK, this could happen, but I wouldn’t say I was sure it was going to happen to me.

What did you show in “Freeze”?

The show kept evolving: there were different iterations of it. In the first show, I had some abstract aluminum sculptures that were somehow crushed up. For the second iteration, I showed some brick walls that looked like they were hanging on the wall: they looked like brick-wall paintings, made of actual bricks but still quite abstract.

Sarah Lucas,

Concrete Boots 98–99, 1999

. Cast concrete, 7 5/8 x 5 1/8 x 11 in (19.4 x 13 x 27.9 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Concrete Boots 98–99, 1999

. Cast concrete, 7 5/8 x 5 1/8 x 11 in (19.4 x 13 x 27.9 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

When was your first solo show after that?

It must have been 1991. Between “Freeze” and the first solo show I had pretty much stopped making work. It was just too expensive and all that stuff was filling up the house: what makes sense while you are in school doesn’t make sense once you are out of school. I found myself just doing much smaller things and using newspapers and bits of photography as material, not big cumbersome things, but things that actually interested me. That’s how I began to bring more social content into the work.

It’s interesting that you speak about social content, because to me your work is also very much about spending time alone: it’s about what people do in their free time. Some of your small sculptures feel like you are just fidgeting with things, and others look like the kind of work that amateurs and hobbyists do. I loved the exhibition of prison art that you curated a few years ago in London, because it highlighted the fact that your sculpture is something that is done to pass time, or perhaps to give value to a time that would otherwise be wasted or perceived as valueless. It’s unemployment time.

Yes, exactly. When we left college, there was this great big dash among the students to get studios. I used to think, “Why do you want a studio if you don’t even know what you’re going to do yet?” Fortunately, I never cared so much about having a studio, and still don’t. After school, I was going out with Gary Hume and I just had a corner in his studio. I can work anywhere.

In some other works of yours there is a sense of idleness, perhaps drinking beer or just sitting around, maybe a bit depressed, smoking a cigarette or sitting on a toilet, staring at the wall. Some of these works also could be read as a parody of a certain idea of Britishness: all that time wasted at the pub . . .

I don’t know if I have ever set out to parody Britishness, it’s just something you can’t really take out of me, I suppose. I am quite typical in some ways, although I’m probably not that typical of British women; I’m more typical of British blokes.

Sarah Lucas,

Edith

, 2015. Plaster, cigarette, toilet, and table, 54 3/4 x 73 5/8 x 38 3/4 in (139 x 187 x 98.5 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Edith

, 2015. Plaster, cigarette, toilet, and table, 54 3/4 x 73 5/8 x 38 3/4 in (139 x 187 x 98.5 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

I also find that your work has immortalized a way of life that in the meantime has disappeared. I remember looking at your work at the same time as I was watching Ken Loach’s movies, like Riff-Raff (1991) and Raining Stones (1993), and retrospectively it seems to me that both your work and his came to chronicle the disappearance of the working class, instead of its emancipation.

That might be true, but I didn’t do that on purpose. Early on, there was a point when I realized that maybe I’m just old-fashioned and can relate to those disappearing worlds. It’s also quite difficult to be objective about those kinds of things. You’re caught up in it, and you don’t really see yourself: you’re just carried away by events. To a certain extent, we are all just the product of the time we live in. You could also say that about being part of a generation, which is something that often comes up when discussing art in the 1990s in London.

Between “Freeze” and your first show, with its legendary title “Penis Nailed to a Board” (1992), where else did you show?

I had actually stopped being bothered about being in other shows. But around 1990, I realized I had a bunch of stuff that I liked, and it coincided with some luck, because I was invited by the gallery City Racing to do a show there, and that’s how “Penis Nailed to a Board” came about. Then Michael Landy was supposed to do a show at Karsten Schubert, and he couldn’t finish his work in time, so instead he invited a bunch of friends to make a group show, and I was one of those. Then another friend of mine was supposed to be doing something in an old shop on Kingly Street and she couldn’t because something had happened in her family, so with two weeks’ notice I got to have that show. Everything happened at once. One thing rolled into another, and I had some works that were finished earlier and some things that I just knocked up, and that turned out to be my breaking moment, when people realized I was up to something, whatever that was.

Where did you show Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992)?

That was on Kingly Street, in a shop. There used to be this organization called Alternative Art, which helped artists to use spaces that were empty in the West End. This was one of those shops, and I was invited to do something in it. In the front of the shop I put the table with the kebab and fried eggs and there was also the pan for frying eggs. Then there was a room in the back with The Old Couple (1991), which is the piece with two chairs and the teeth and the penis. And that was it, which I thought was brilliant. I made both of those pieces quite quickly right before the show. I didn’t have a lot of time to mess about. It amused me to think that people would come in to see the table with the kebab. I think it’s quite nice to show just one thing, just like that.

Sarah Lucas,

Self-portrait with Fried Eggs

, 1996. C-print, 60 x 48 in (152.4 x 121.9 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Self-portrait with Fried Eggs

, 1996. C-print, 60 x 48 in (152.4 x 121.9 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

What kind of audience came to see the Kebab piece?

A lot of people just stumbled on it by seeing the table from the window. The three shows—the one at Karsten Schubert, “Penis Nailed to a Board,” and “The Whole Joke,” which featured Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab —overlapped, so a few people in the art world saw all three. I remember Lawrence Luhring came to see Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab , and he was very encouraging. Charles Saatchi bought it, which was weird. My jaw just dropped. I had no expectations. I also met a lot of people during that time who became my good friends for the rest of my life.

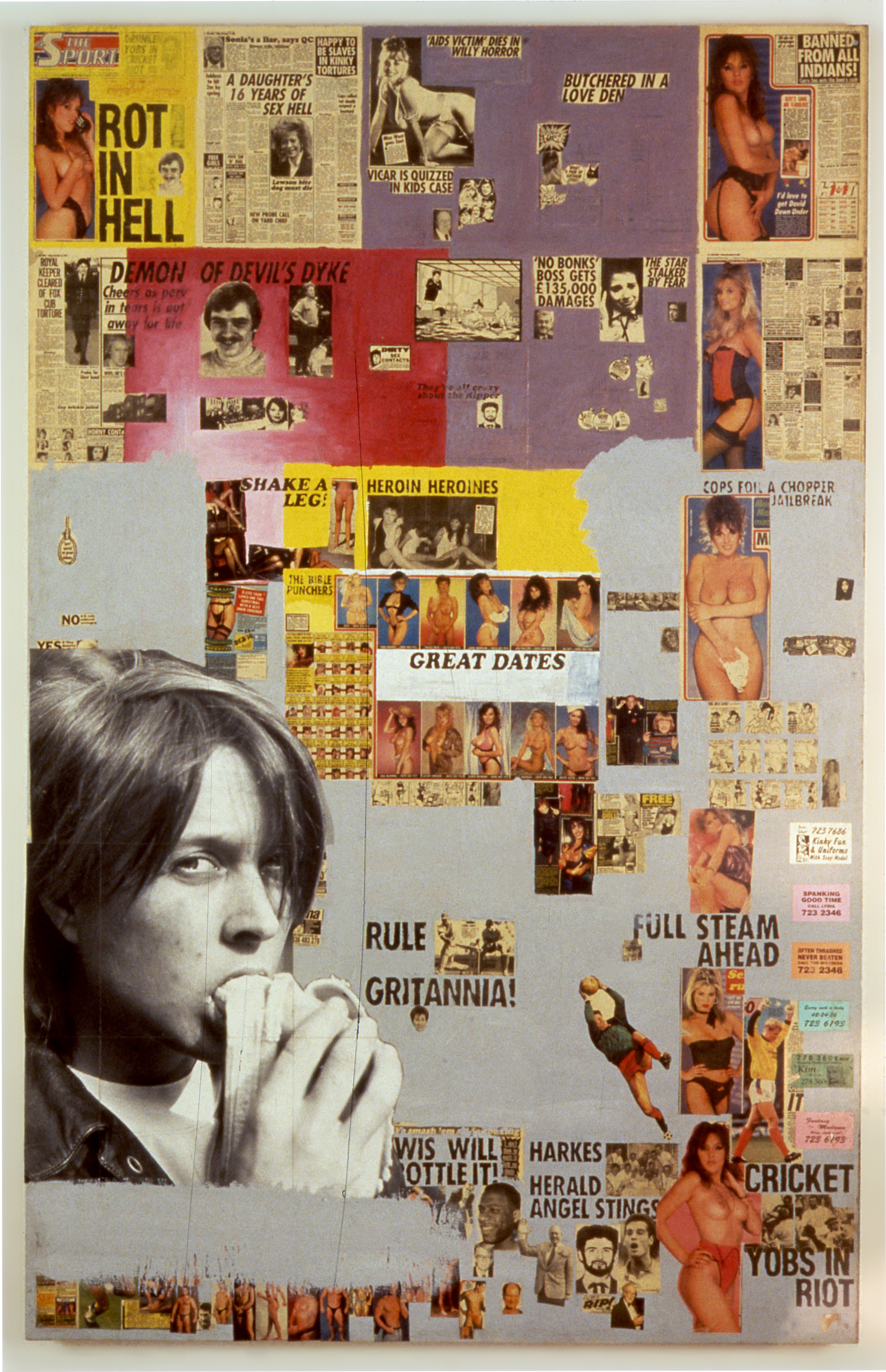

Can you tell me more about “Penis Nailed to a Board”? What did the show include?

It included the big posters: Monster Hooker (1991), Great Dates (1992), the ones with the newspapers. There was a piece with a bicycle upside down that was turned into a kind of plinth on which were six or seven photographs of a naked bloke with fruit and veg covering and replicating his genitals. And then there was Soup (1989), the picture with the knobs, and the board game Penis Nailed to a Board (1991). It was simple, but it felt like I was finding my own voice.

The whole show must have felt rough and aggressive, with the large tabloid collages. Those pieces are usually read in relation to certain exploitative stereotypes of femininity. But to me, a piece like the bicycle sculpture connects to the tradition of Arte Povera, and before that to the Surrealist fascination with everyday objects and domestic spaces, not to mention Duchamp and his wheel. Were any of these references playing an active role in your work at the time?

You have to be careful when it comes to influences. All those ideas might have been there, but they become more interesting when you project them onto the sculpture after it has been made. Personally, I wasn’t concerned about influences or other people’s work: I was more concerned about making something that, however weird, was something I could stand for. It was more about me than about anybody else’s work. Then again, you can’t take those references out of it, but it’s not like I placed them in there. I think I’m actually quite myopic when working. Maybe those ideas say something more interesting about the viewer than about me. The funny thing about the large tabloid collages is that I hated all that tabloid stuff. It was only when I started making artworks out of them that I started enjoying them. When I first moved to my house in London, I used to get a million pizza leaflets through the door every day. It used to drive me nuts; it used to make me furious. And then one day I just stuck them all to the front door, and after that, I started liking them.

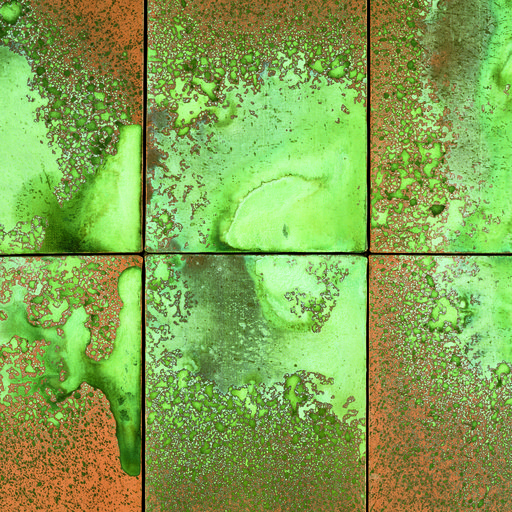

Sarah Lucas,

Great Dates

, 1992. Collage and paint on board, 88 x 56 1/2 in (223.5 x 143.5 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Great Dates

, 1992. Collage and paint on board, 88 x 56 1/2 in (223.5 x 143.5 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

That’s always the dilemma with works that engage popular culture: Is the work critical or complicit, even celebratory?

Those works are pretty critical, but they aren’t as simple as saying I like or dislike that material. Anytime you use something, no matter how disgusting, there has to be some pleasure in it, if only because you transform it and you do something with it, rather than just being passively assaulted by it. But at the same time, I remember that with the tabloid stuff, the funny thing was seeing other people’s reactions to it, because each viewer brings her own prejudices to the works. It’s about turning things around, really, and the realization that looking at art is a self-conscious business.

Did you feel there was any difference in the reaction to these works, particularly with the tabloids, depending on who the viewer was?

I don’t think I make things for a specific type of public. I like to be as broad as possible. I’m not anti-intellectual or anything; I just think things can operate on different levels. I want to make works that anybody can relate to, not only the people from the art world, but also the ordinary man or woman on the street, from the particular class I came from.

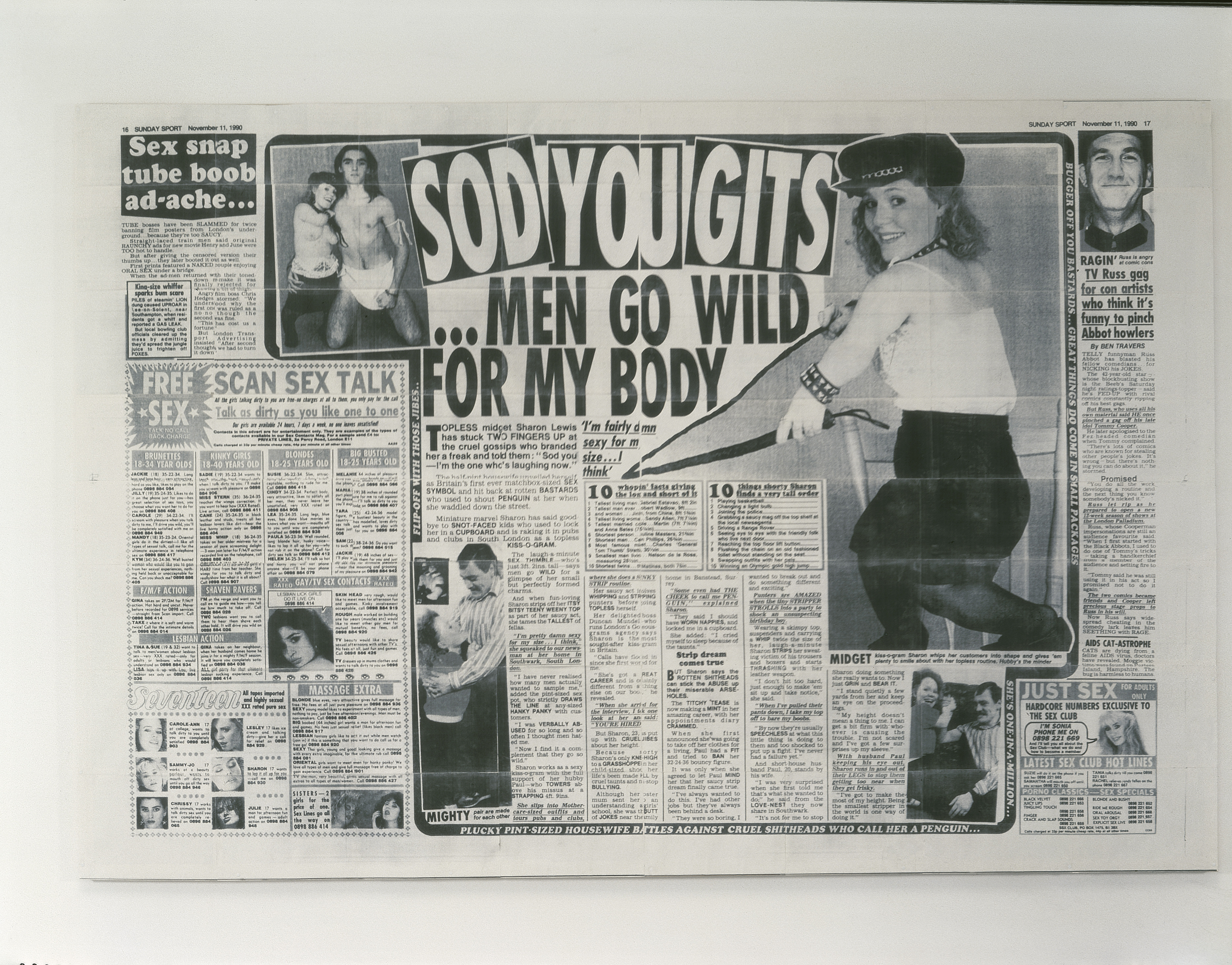

And what happened when your own work ended up in the tabloids? I’m sure there were plenty of occasions in which your work was attacked in the press: it’s another British tradition.

The weird thing about the tabloid press is that it exists in its own reality: it just follows itself and feeds itself. It’s like a novel with its own characters.

So you were never really devoured by the tabloids? Not even at the time of “Sensation”?

Well, you know, just the usual twenty years of remarks about my vulgarity, and a bit of joking and one-liners about my work, not too bad. They’ve probably got bigger fish to fry.

Sarah Lucas,

Sod You Gits,

1991. Photocopy on paper, 85 3/4 x 124 in (218 x 315 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Sod You Gits,

1991. Photocopy on paper, 85 3/4 x 124 in (218 x 315 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Would you say your work was also about the culture of celebrity that was emerging in the 1990s, of which tabloids were an early expression? The defamation of character, the paparazzi, the cannibalism of public figures . . .

All that was very much in the air, but when I look back on it now, I think that at the time I was quite keen to be different. It used to get on my tits, thinking that I was part of the same scene as everybody else. I was trying to find my voice, not to make work about other art around me.

Speaking of finding your own voice and being yourself, did you feel the production quality of your work was different from that of your colleagues? In your work there was always a sense of urgency, of basicness and baseness, while others were getting slicker.

Early on, yes, I think I wanted to keep things simple, rough-and ready, almost a kind of antistyle, but that also changed very quickly. I like the idea of not having a style and just keeping things together with ideas and an attitude. I felt that it was a very radical thing. But then all this grunge stuff happened, and I was just seen as a part of that, and I didn’t want to be assimilated that quickly. I am really not grungy at all. I might be very homemade, and I like making things, and I might be using quite cheap materials, but I am always quite precise, and think of myself as a formalist even.

Maybe the confusion arises because of the way you play with craft and bricolage, with things that people do to pass time.

More than anything, I think my early work was related to a certain idea of alternative culture. I left home at sixteen, started squatting, and all the stuff that came with that approach. Even my first shows were in alternative spaces. For me, it wasn’t even a strategic choice: it just needed to be that way; I needed to be prepared to be alternative out of necessity, because if I was going to wait about until I could afford a bloody washing machine in a flat, then it was going to be a lot of years. It wasn’t possible for me to just become some regular blue-chip artist, and I wasn’t even interested in it. I wanted to carry on doing these things, on the ground, with my peers, in alternative ways.

Sarah Lucas,

Sex Baby Bed Base

, 2000. Bed case, chicken, T-shirt, lemons, and hanger, 70 7/8 x 52 1/2 in (180 x 133.5 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas,

Sex Baby Bed Base

, 2000. Bed case, chicken, T-shirt, lemons, and hanger, 70 7/8 x 52 1/2 in (180 x 133.5 cm). © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Do you think The Shop, the project you started with Tracey Emin in 1993, was another type of alternative space?

Yes, The Shop came out of that attitude.

The Shop was a kind of open studio and an alternative space, but also operated like a real shop, where people could buy artworks and strange souvenirs. It ran for six months in a rented storefront in the East End. Did you have any model in mind when you started? Any connection with other artists’ shops or restaurants or other alternative spaces?

No. It was just that I was sitting in an Indian restaurant in Brick Lane one day with Tracey, and I had just moved out of the studio with Gary, because I didn’t really use it and things had gotten a bit tricky with us, and I thought, “Well, I’ll just work at home, then.” But my home at the time was quite small. And as soon as I made that decision, I thought, “I’m going to get bored knocking about here on my own.” I was talking to Tracey at lunch about maybe getting a studio together, and one of us came up with the idea to get a shop. It was probably her, as she’s very canny about business. We went around looking at what was empty and got a shop for six months. We started with absolutely nothing, with no particular idea. There were other things going on at the time: artists running galleries, using empty shops or big warehouses. . . In the same year that we had The Shop, there was “A Fête Worse Than Death,” which was a kind of street party, with art. The Shop wasn’t really premeditated: we just did it.

Who came to The Shop?

People just came in off the street. Of course there were friends, people from the art world, but also just people walking by. Everything was affordable, some things were really cheap. On Saturday nights we used to stay open all night, and Brick Lane was one of the few allnight places then. It was interesting because we started with nothing whatsoever, and nobody knew we were doing it. And in the space of six months, people were coming by. Max Hetzler, I still remember, came by at three in the morning. So it just took off, I suppose.

The entire art system was changing in London around that time. The magazine Frieze had just started and new galleries had opened. It’s around that time that you showed at White Cube and at Anthony d’Offay.

When I did the show at d’Offay, it was really with Sadie Coles, who was working there.

And that’s when you showed the self-portraits?

I had showed some but in a different configuration, as a kind of sculpture, in a group show in a warehouse, so that must have been 1989 or 1990.

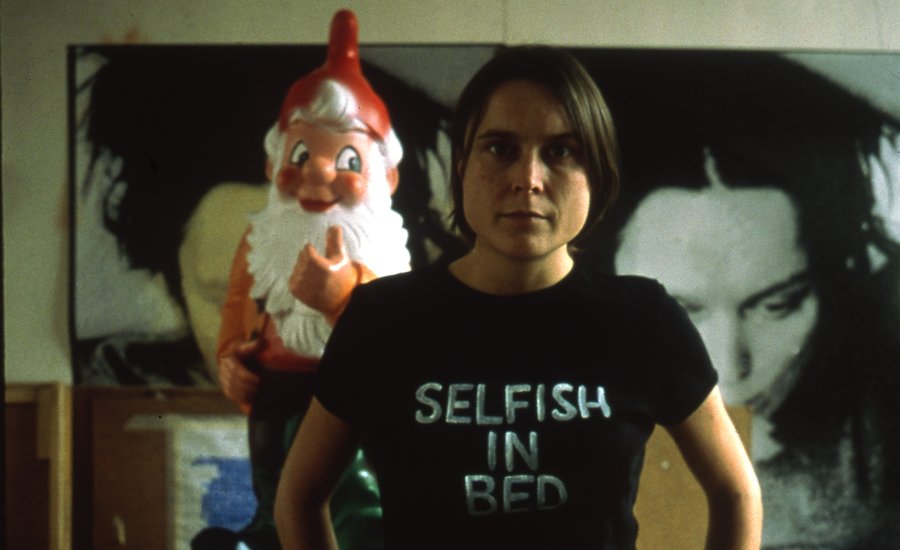

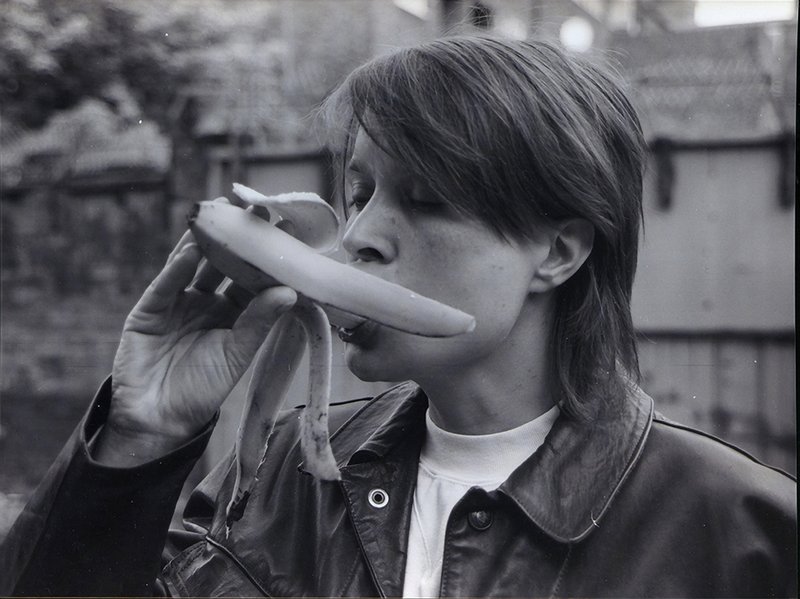

How did the portraits come about?

In a sense, they are not self-portraits, because it’s not me taking the picture: they were all shot by someone else, but again, it’s a way of doing things collaboratively or communally, another form of alternative creativity. A lot of art requires input from others, whether you label them assistants or friends. People don’t like to hear that, particularly now, when we are living in a super egocentric time. Instead, my self-portraits are very much about relationships, about being with someone else, and being looked at by or playing with someone else. They are me, but being me is always about being with others. Art takes a lot of people. A life takes a lot of people.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Sarah Lucas on Her Art, the Venice Biennale, and Learning to Be Less Abject

The New YBAs: 8 Next-Gen Stars of British Art, from Ryan Gander to Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

[related-works-module]