He created a big whale in a forest at the furthest tip of South America, and mocked up a rebellious dinner party on the roof of the Met in New York. But do you also know that this important Argentinian artist fashioned his first work from a video game? Or that he doesn’t really think of his art as sculpture, but more as a kind of highbrow housekeeping project?

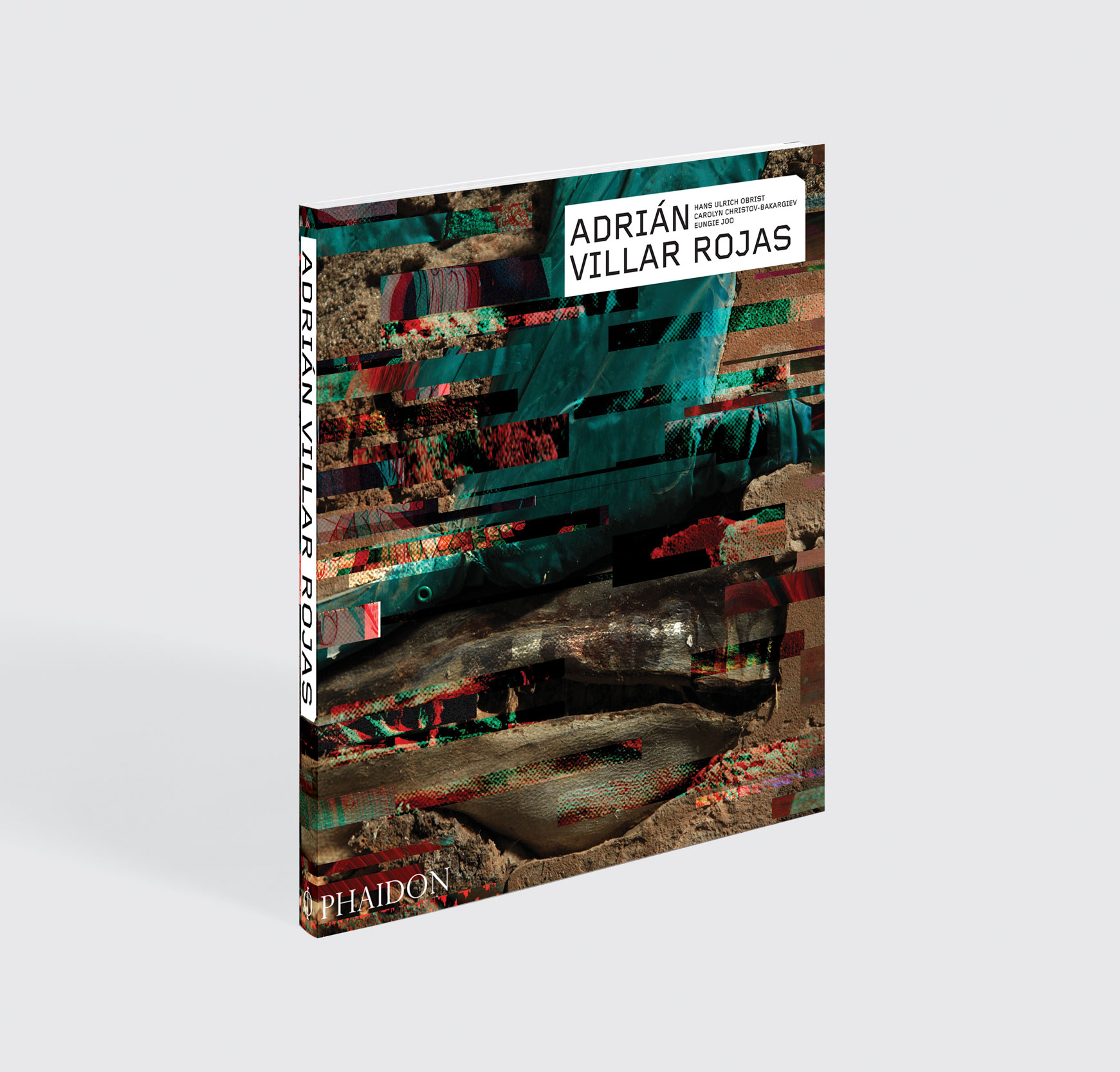

Phaidon's newly published Adrian Villar Rojas Contemporary Artist Series book is the first to explore the fascinating career and fantasy-driven worlds created by Villar Rojas, whose colossal installations are transitory and so cannot be collected; they simply disappear, or decay over time. His practice confronts us with ideas of obsolescence and extinction, but also with the possibilities of humankind and its endless imagination. He has had solo exhibitions in prestigious institutions, such as MOCA Los Angeles, MoMA PS1 in New York and the Serpentine Galleries in London, and has represented Argentina at the Venice Biennale.

Yet his works can, at times, be a little bit hard to understand. So, by way of a guide, here are a few edited highlights from curator Hans Ulrich Obrist's interview with Villar Rojas, as featured in the new book.

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Theatre of Disappearance, 2017. Nylon-printed and polyurethane CNC-milled reproductions of human and non-human animal figures, food and artefacts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art's permanent collection, coated in bespoke automotive paint, porcelain tiles, diamond-plate flooring, hollybush hedges, public bar, signage, benches, adapted and repainted pergola. Installation view, The Roof Garden Commission at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2017. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Theatre of Disappearance, 2017. Nylon-printed and polyurethane CNC-milled reproductions of human and non-human animal figures, food and artefacts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art's permanent collection, coated in bespoke automotive paint, porcelain tiles, diamond-plate flooring, hollybush hedges, public bar, signage, benches, adapted and repainted pergola. Installation view, The Roof Garden Commission at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2017. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

His first work was actually a series of screen captures from a video game.

OBRIST: Which piece do you consider your first artwork that’s no longer student work and would be number one in your catalogue raisonné?

VILLAR ROJAS: In 2003, my high school friends and I would often meet in a cybercafé to play Counter-Strike, a multiplayer videogame of terrorists versus anti-terrorists. Something that fascinated me about it was that when you were ‘killed’, you remained in the game, able to wander through the different levels without any agency until the moment all the other players had also died.

In this way, I could become a ghost, flying to the liminal spaces of the programme, which uncovered digital territories and generated glitches that distorted the game’s orderly landscapes and architecture. I started to let myself be killed to investigate and take screenshots of this phenomenon. Then I edited these screenshots and sent them in a portfolio to an open competition for emerging artists held by the major Argentinian gallery, Ruth Benzacar

In 2017 Rojas created The Theater of Disappearance, a sculpture of a dinner party on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum with the help of Hollywood special effects professionals. He modeled everything on objects in the Met’s collection, and aimed to upset the politics of this venerable institution.

OBRIST: These figures and objects were inspired by the Met’s collections. How did you choose from thousands of years of cultural production? What were you looking for in the objects you took inspiration from?

VILLAR ROJAS: There is no inspiration, but rather a concern related to the status of the displayed objects and the Met’s political agency as it produces the context in which these objects are generally encountered by the public. During the research process, the extreme hierarchical and departmental structure of the museum immediately manifested itself, generating both obstructions and an opportunity to reflect on what lies beneath the surface of so-called encyclopaedic institutions like this one. I was looking for alternative vertices in the departments’ official history, many of which copied the model of eighteenth-century, mostly European museology, but also in the demarcation of the departments themselves. I looked into the forgotten peripheries: Cyprus in Greco Roman, the Amerindian woman in what’s perversely named the American Wing, but primarily includes colonial and early United States Republic artefacts.

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Most Beautiful of All Mothers, 2015. Cement, resin, white polyurethane paint, lacquer, stratified organic, inorganic, human and machine-made matter collected in Istanbul, Kalba, Mexico City and Ushuaia. Installation view on the shore of Leon Trotsky’s former house on Büyükada Island, 14th Istanbul Biennial, 2015. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Most Beautiful of All Mothers, 2015. Cement, resin, white polyurethane paint, lacquer, stratified organic, inorganic, human and machine-made matter collected in Istanbul, Kalba, Mexico City and Ushuaia. Installation view on the shore of Leon Trotsky’s former house on Büyükada Island, 14th Istanbul Biennial, 2015. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

The American Wing could be seen as the subconscious of the museum, which betrays a series of meta-postcolonial interpretations: its entrance is a vast atrium filled with neoclassical sculptures in front of a reconstructed façade from a Wall Street bank, and in front of that venerated and preserved façade one encounters a nineteenth-century white marble sculpture called Mexican Girl Dying, possibly the most profound expression of culture within the Met. Being someone from the South of America, to see all these elements in a clear state of conflict constituted a very visceral experience. This becomes even more staggering when we consider that the rise of capitalism can be traced to the conquest of the ‘New World’ by the Spanish Empire; gold and silver spoils arrived in Europe and formed a proto-international monetary system.

The American Wing is the blind spot of the institution and to make that evident was one of the main axes of my project there. I also wanted to look for objects from everyday life that are untouchable according to international museum display codes. This is very palpable when confronted with ergonomically designed artefacts conceived to be held or worn, which inside a freezer-like vitrine are held by tiny bespoke devices, each armature forcing this once animated thing into cryogenesis. This is the vocabulary of institutional preservation interpretation-separation, which imposes itself with all its force over that of the humble and defenceless daily life artefact, so fragile and silenced. I was interested in tools and utensils that could create a dialogue with the museological device and at the same time be revived, activated and occupied when returning to the human anatomy.

OBRIST: And then you incorporated the human forms within this.

VILLAR ROJAS: We found a team of Hollywood VFX experts who could 3D scan people with the same accuracy as we were 3D scanning the objects. We generated computer files of the bodies of fifteen people, including a seventy-year-old woman and a five-month old baby, then amalgamated them digitally so people were wearing and using the now untouchable artworks. Each ‘sculpture’ was digitally fabricated directly from the file, without any human intervention, and painted either black or white. A visible layer of what looks like dust was then applied to each sculpture, accumulating in its nooks and crevices. This uniformity generated a sense of ambiguity both regarding the origins of the Met artefacts and the people, obliterating and questioning all the cultural readings that are carried into our everyday constructions.

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Theatre of Disappearance, 2017. Hand-painted reproduction of Piero Della Francesca’s Madonna Del Parto (1450–75), transparent film on glass walls, mirror-clad column. Installation view at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (ground floor), 2017. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Theatre of Disappearance, 2017. Hand-painted reproduction of Piero Della Francesca’s Madonna Del Parto (1450–75), transparent film on glass walls, mirror-clad column. Installation view at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (ground floor), 2017. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

He continued this theme with other shows of the same name at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA in Los Angeles, Kunsthaus Bregenz in western Austria, and NEON in Athens, Greece. Each exhibition artfully undermined the institution, and the idea of perfect, permanent collection.

OBRIST: You’ve created more projects under this title, The Theatre of Disappearance – with the Kunsthaus Bregenz, NEON in Athens and the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. What is The Theatre of Disappearance? Why is it spreading across continents?

VILLAR ROJAS: After a period of internal discussions about my relation to spectacle and world-building, I accepted that I could no longer think of what I do in terms of producing discrete ‘pieces’ or ‘works’ or even ‘units’ to be exhibited in a certain ‘space’. I’ve increasingly found myself quite uncomfortable with all this vocabulary that draws a clear line between content and container – ‘artwork’ and ‘art space’. Therefore, I decided to radicalize the deconstruction of this ontological difference. Every invitation represented a platform with its own variables and as I begun to understand each of these ‘invitations’, and started to interweave the sites, a geo-political-philosophical interaction was generated between them all.

I see The Theatre of Disappearance as a sort of deconstructive homage to Western art, as if I were mourning it from Greece to the United States. This is what interconnects these exhibitions: the intention to trace a panoramic view of the West as a human project – I should say, the one of a very specific group of humans – with the motivation to provoke a metaphorical speculation, with no documentary or scientific pretensions. Each museum-institution represented a very precise place for me to situate knowledge production and identity construction in coevolution with the cities and countries that host them. The projects at the Met and MOCA are the two extremes of this arc: the East and West Coasts of the United States. The East Coast embodies the thriving colony that has overtaken its colonizers on the world stage, and that offers through its museological apparatus – in this case, the Met – an American version of ‘History’.

Adrián Villar Rojas, The Theatre of Disappearance, 2017. Freezer, white silicone, recreation of Homo Ergaster skeleton ‘Nariokotome Boy‘, cast of orangutan’s foot, octopus slice, cold cuts and banana peel (from Rinascimento, 2015), igneous rock, vanadinite crystal, mollusc shells, butterfly wings, dried fruits and vegetables, fungi, cake, hippocampus, collected in Los Angeles, Erfoud, Istanbul, Kalba, New York, Rosario and Turin, 210 x 82 x 120 cm. Installation view at the Geffen Contemporary at MoCA, Los Angeles, 2017. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

At the other extreme is the West Coast, which is moving from a much more self-confident and sunnier present to a future directed by a highly dynamic society with the highest GDP in the United States, the post-human Hollywood of the blue screen and nearby Silicon Valley, which operates a new techno-surveillance-Capitalocene logic whose ‘utopian horizon’ is to develop an app for every aspect of life’s rugosity. If the Met is the safety box where the material traces of the past are preserved, the West coast is where the totality of human noise will live digitally in a data centre that’s no bigger than a football stadium in infinite and rhizomatic expansion. This wasn’t a minor consideration, given that the arc of presentations would open in New York City and be closed in Los Angeles.

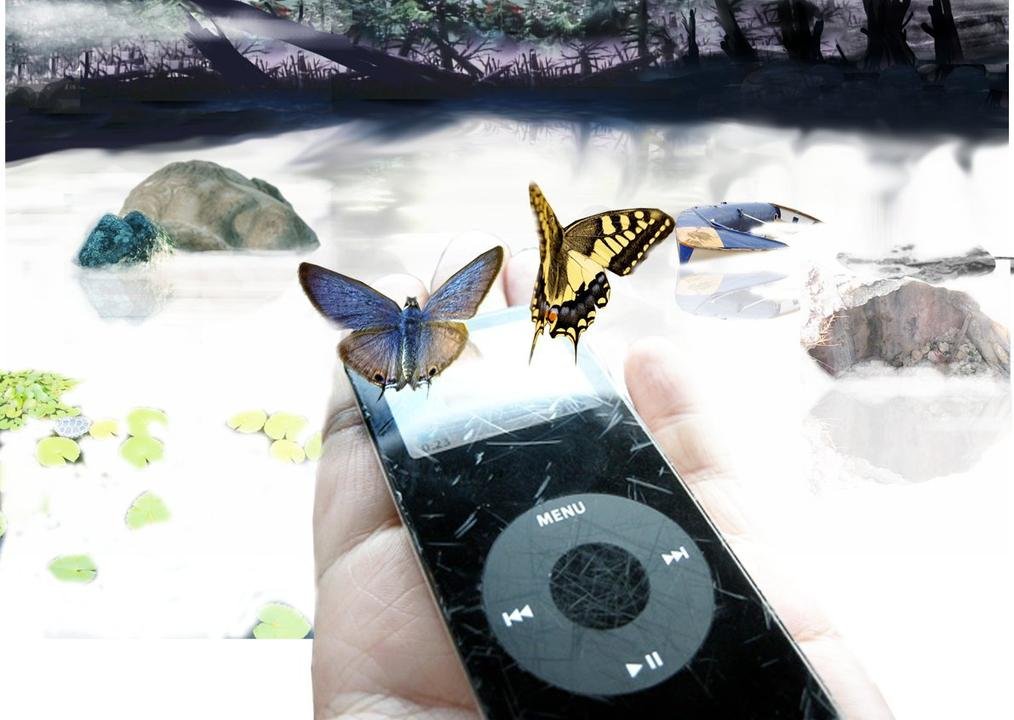

ADRIÁN VILLAR ROJAS - Poemas para terrestres, 2012 - From the series Lo que el fuego me trajo (What fire has brought to me), 2013

Adrián Villar Rojas, From the series Lo que el fuego me trajo (What fire has brought to me), 2013 - BUY IT NOW ON ARTSPACE

Adrián Villar Rojas, From the series Lo que el fuego me trajo (What fire has brought to me), 2013 - BUY IT NOW ON ARTSPACE

The Kunsthaus Bregenz moment can be read as a sort of mourning-homage to ‘Western Reason’ under the form of a tribute to the guardians of Peter Zumthor’s architectural masterpiece: the staff of the museum, the people who’ve been working there since its opening in 1997, carefully looking after every inch of the premises.

How moving it was to be in Bregenz, a city with a population of 28,000, and finding this pristine tower solely dedicated to creating the most perfect experience for encountering and savoring contemporary art: the thick concrete walls, the sleek design, everything was shouting, ‘I’m Europe, I’m reason, I evolved and have reached the limits of the project of modernity, positivism and enlightenment’. It was difficult for me to disassociate this building from the idea of subterranean vaults that still probably hold looted art – and plenty more – from the Second World War. Austria, or the Holy Austro-Hungarian Empire, protected the West against constant Ottoman siege, precisely from the lands of what once had been Ancient Greece, and was from the mid-fifteenth century in the hands of the Osmanli dynasty’s Constantinople. Finally, in Athens, the site of my project was the National Observatory, founded in 1842 and located on the Hill of the Nymphs, one of the city's seven historic hills.

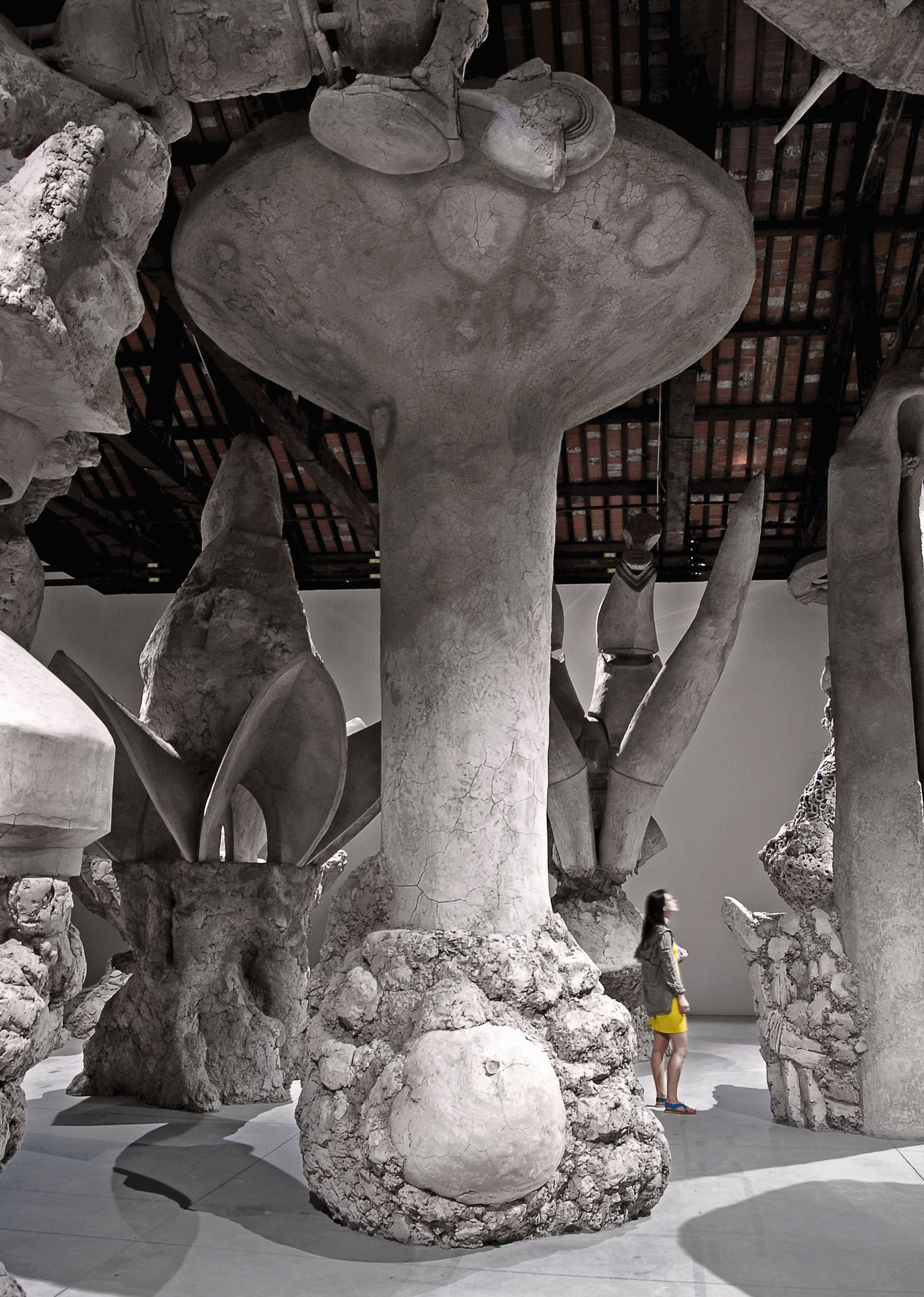

Adrián Villar Rojas, Return The World, 2012. Unfired local clay, cement, metal, wood, seeds, plants. Installation view at the Weinberg Terraces, Documenta 13, Kassel, Germany, 2012. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Adrián Villar Rojas, Return The World, 2012. Unfired local clay, cement, metal, wood, seeds, plants. Installation view at the Weinberg Terraces, Documenta 13, Kassel, Germany, 2012. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

It was at the time the single most advanced piece of technology on the whole continent and – for some years – in the world. Its existence represented the re-inscription of the Greek cultural frontier into the European orbit after almost 400 years of Ottoman domination, so its richness resided less in its relation to the history of science and more in the history of religion and geopolitics. I can’t think of a more powerful statement than to say that the request to grow fields of corn in the grounds of the National Observatory generated five months of political and legal negotiations and four court hearings, which we eventually won. A lesson from Greece: the earth below our feet can be extremely sensitive.

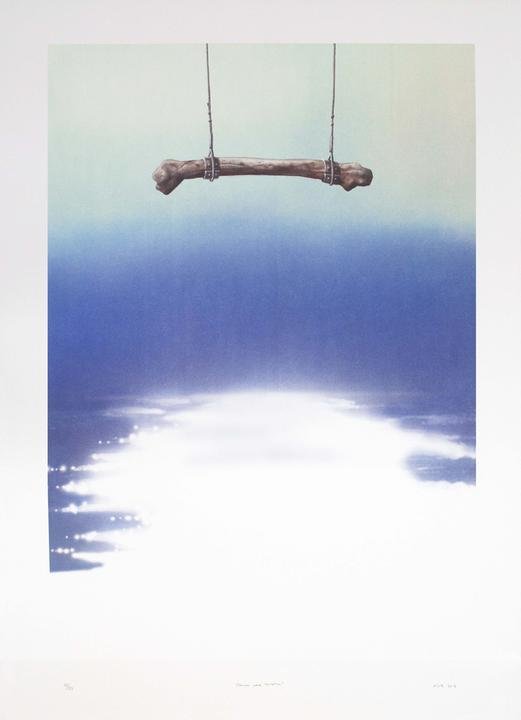

ADRIÁN VILLAR ROJAS- Poemas para terrestres, 2012

Adrián Villar Rojas, Poemas para terrestres, 2012 - BUY IT NOW ON ARTSPACE

Adrián Villar Rojas, Poemas para terrestres, 2012 - BUY IT NOW ON ARTSPACE

He isn’t, as you can imagine, one for classifications. In fact, rather than thinking of him as a sculptor, he prefers to draw comparisons with other, less highbrow activities, such as housekeeping.

OBRIST: You create in multiple dimensions: you’re a sculptor, an architect but also a filmmaker, draughtsman, etc. You’re a true renaissance artist. Do you agree?

VILLAR ROJAS: I think that classifying what I do goes against how I would like to think within a field as generous and open as what has been called ‘contemporary art’ and which is also undoubtedly a classification less useful for the practice itself than for other purposes (commercial, political, cultural, advertising, academic, and so on). I live, like everything that exists, in a 4D reality; I produce signs that give an account of this ‘apparent’ condition.

OBRIST: Your work within institutions often confronts and challenges, altering – even arguably improving – the pre-existing conditions of the institutional spaces. Is that an intentional challenge, or a side effect of the scale your projects demand?

VILLAR ROJAS: I prefer to use a term that appeared in my vocabulary thanks to my collaboration with [writer and curator] Helen Molesworth: ‘housekeeping’. I feel it suits what I do better than phrases like ‘challenging the architecture of institutions’. Housekeeping means someone is taking care of a specific place and its status; someone is sweeping the floor, painting the walls, checking the number of electricity outlets. Housekeeping is a type of labour that enables other types of labour (and life) to happen, and when it’s well done, nobody sees it. And this is a quality I’m interested in, committed to and that I want to embody. I want to cooperate with my hosts and allow them to use me as a platform for transformation.

‘The container generates meaning’, and ultimately, the ‘container’ is always interdependent with the operations and practices of individuals, so in order to achieve whatever you wish to do, you have to negotiate with people. The architecture is just one component. This is the biopolitical agency of housekeeping, and it’s part of what I call the sustained ‘host/parasite’ relationship that I develop with the institutions I engage with.

Adrián Villar Rojas, Mi Familia Muerta (My Dead Family), 2009. Unfired local clay, rocks, 3 x 27 x 4 m. Installation view in the Yatana Forest, 2nd End of the World Biennial, Ushuaia, Argentina, 2009. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Adrián Villar Rojas, Mi Familia Muerta (My Dead Family), 2009. Unfired local clay, rocks, 3 x 27 x 4 m. Installation view in the Yatana Forest, 2nd End of the World Biennial, Ushuaia, Argentina, 2009. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Oh, and as you may know, he created a life-sized clay whale in the farthest tip of South America. It wasn’t easy to find. And that was sort of the point.

OBRIST: In 2009, in Ushuaia for the End of the World Biennial, you created your monumental work, the life-size blue whale in the Patagonian Yatana forest Mi familia muerta (My Dead Family, 2009) constructed entirely of unfired clay.

VILLAR ROJAS: It’s been ten years since the whale in Ushuaia, and just last week I saw a news report of a young humpback whale that had somehow drowned and its body had washed up in a remote Brazilian rainforest, a mangrove close to the mouth of the Amazon river. The similarities, the scale of the huge corpse lying on its side surrounded by green trees and broken branches, were highly disturbing to me. The first time I went to Yatana, I was immediately fascinated by the idea of people wandering around a forest, nowhere near the biennial site, getting lost, seeing no signage or directions, then finding nothing, or eventually finding a whale made of earth, with its skin sprouting fungus and plants. I wanted the people who found our whale, emancipated from the expectations of trying to find an artefact that was part of the biennial apparatus, to have the feelings and questions that those who discovered the humpback in Brazil must have had: How did this get here? Who did this? Is this some end-of-the-world scenario? What back in 2009 could be read as a sci-fi image or a fantasy, has now become a mundane transcription of the climate crisis: a bloated, decomposing cetacean beached in a forest is no longer surreal, it is a political and environmental reality.

Adrián Villar Rojas, Ahora Estaré con mi Hijo, El Asesino de tu Herencia (Now I Will Be With My Son, The Murderer of Your Heritage), 2011. Unfired local clay, cement. Installation view at the Argentinian Pavilion, 54th Venice Biennale, 2011. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Adrián Villar Rojas, Ahora Estaré con mi Hijo, El Asesino de tu Herencia (Now I Will Be With My Son, The Murderer of Your Heritage), 2011. Unfired local clay, cement. Installation view at the Argentinian Pavilion, 54th Venice Biennale, 2011. Artwork © Adrián Villar Rojas

Phaidon's Adrian Villar Rojas Contemporary Artist Series book is the first to explore the fascinating career and fantasy-driven worlds created by the acclaimed Argentinean artist. This is the first book to include all of Villar Rojas' most significant projects, featured in international biennials such as Venice, Documenta, Shanghai, and others. It includes contributions from Hans Ulrich Obrist, co-director of exhibitions and programmes and director of international projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London; Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev,director of the Museum Castello di Rivoli in Turin; and Eungie Joo, contemporary art curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.