Aside perhaps from Bible stories, no body of literature has so heavily informed Western art than Greek and Roman myths. And no wonder: since the Renaissance until at least the advent of Modernity, Classical civilization was revered in Europe as the high-water mark of human progress, and its legacies were imitated, for good and for ill, and with wildly varying degrees of accuracy, by societies far beyond the Mediterranean’s sun-kissed shores.

Today, centuries after Titian painted his Bacchus and Ariadne (1523), Rubens his Leda and The Swan (1602), and Poussin his Landscape with Orpheus and Eurydice (1650-51), Classical mythology remains a perennial cultural touchstone, and on the most everyday level: we wear sneakers named after the Greek goddess Nike, eat chocolate bars named after the Roman god Mars, even practice safe sex using Trojan prophylactics.

Here, we bring together five works by contemporary artists that draw on antiquity’s teeming cast of heroes, deities and monsters. While they have their origins in ancient narratives, each speaks to urgent, present-day concerns, among them religious fundamentalism and the shifting sands of masculinity, the legacy of colonialism and the hilarious, heartbreaking distance between our romantic fantasies and brute reality. Myth, in these works, is not a set of dusty stories, but a living, breathing force.

ANDRES SERRANO - Piss Elegance, 2004

Andres Serrano’s 1987 photograph Immersion (Piss Christ) is by any measure one of the most controversial artworks of the late 20th-century. Depicting a small plastic crucifix submerged in a tank of the lauded – and lambasted – American artist’s own urine, it was the subject of vehement religious protests, and was weaponized by members of the Republican Party in the pre-millennial culture wars, leading to a cut in the US taxpayer-funded National Endowment for the Arts. Serrano himself has said that: “I had no idea Piss Christ would get the attention it did, since I meant neither blasphemy or offense by it. I’ve been a Catholic all my life, so I am a follower of Christ”.

In his photograph Piss Elegance, the artist swaps out the Messiah for a female, and decidedly pagan, Greco-Roman figure. Swimming, once again, in Serrano’s amber pee, she might (in a sly reference to Christ’s message of love) be the goddess Aphrodite, or else the hero Perseus’ mother Danaë, who was impregnated by Zeus when he visited her in the form of an – ahem – ‘golden shower’. Either way, Serrano’s playful, oddly beautiful shot contrasts the robust earthiness, indeed the humanity, of Classical religion with the fragile puritanism of those who seek to speak for the Christian God.

VIK MUNIZ - Medusa Marinara, 1999

Able to turn unwary humans to stone with a single glance, the snake-haired Medusa is one of Classical mythology’s most iconic monsters, and has captured the imagination of such artistic titans as Benvenuto Cellini, Antonio Canova, and Arnold Böcklin. Surely art history’s greatest gorgon, however, is Caravaggio’s Medusa (1597), in the Uffizi, Florence, a painting that depicts her shocked expression at the exact moment she is beheaded by Perseus. If we can draw our eyes away from the blood that issues in Tarantino-esque gouts from her neck, we might contemplate an enduring mystery: why did the (male) Caravaggio give this (female) monster his own face?

The celebrated Brazilian artist Vik Muniz’s work Medusa Marina transposes Caravaggio’s gorgon from the canvas to a porcelain pasta dish, recreating her in daubs of transfer-printed tomato sauce. As we work our way through a serving of (snake-like) spaghetti, more and more of the image is revealed, until finally she stares us in eye. According to Classical mythology, Medusa’s ability to petrify humans with her glare persisted after her death – indeed, Perseus used her severed head to turn the leviathan Cetus to stone. Perhaps that accounts for the heavy feeling diners experience, after scoffing a bellyful of pasta from Muniz’s witty tableware.

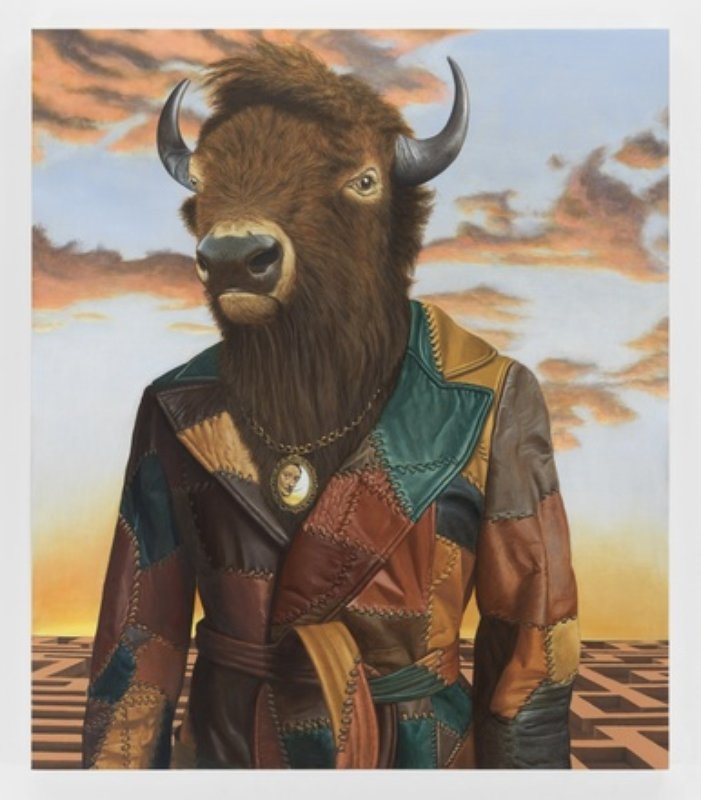

SEAN LANDERS - Buffalo Minotaur, 2017

The monstrous love-child of the sea god Poseidon and Pasiphaë, wife the Cretan King Minos, the part-human, part-bull minotaur was imprisoned at birth in a vast labyrinth beneath the palace of Knossos, in order to hide the monarch’s shame at being cuckolded by a deity. There it remained, feasting on the flesh of young Athenians sent in tribute to the island kingdom, until it was slayed by Attic prince Theseus, helped by Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, who gave the young hero a ball of twine, allowing him to navigate his way out of the monster’s dank, subterranean maze.

In Sean Landers’ print, the acclaimed US artist relocates the minotaur from the Mediterranean to the American plains, giving it a buffalo’s head and a patchwork leather jacket, stitched from what might be taurine or human skin. At its back, an endless bronze and azure sky rises above a terracotta labyrinth, while at its neck it wears a pendant bearing the anomalous image of the legendary Spanish surrealist, Salvador Dali. The culture of Greek antiquity is, of course, central to the USA’s democratic self-image – witness the neo-Athenian architecture of Washington’s Capitol Hill. And yet, Landers’ proud, ruggedly handsome demi-god seems to be not so much a tyrant’s shameful, murderous secret than a symbol of the American First Nations, who – along with the continent’s buffalo – were slaughtered on a genocidal scale by European colonists.

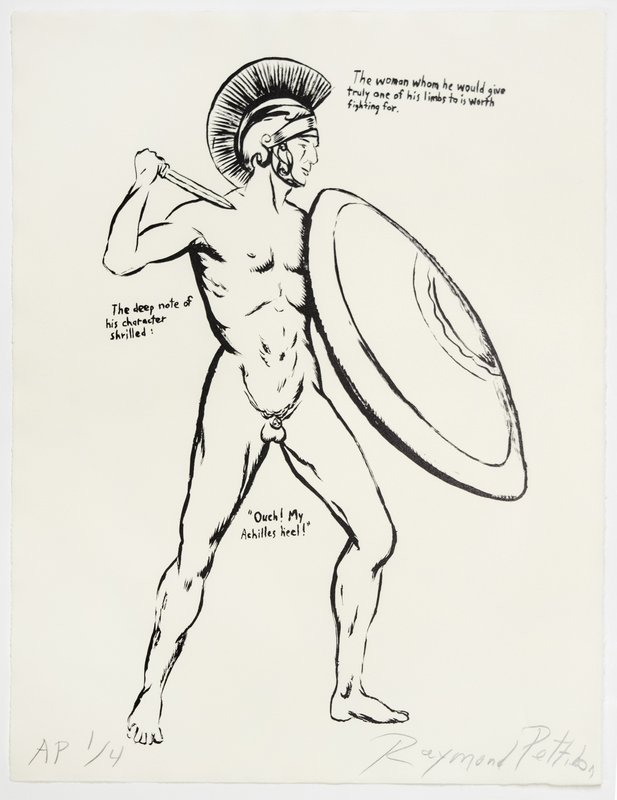

RAYMOND PETTIBON - Untitled (Achilles Heel…), 2018

One of the most complex characters in The Iliad, Achilles is a Greek champion who, despite his apparent imperviousness to physical harm, spends much of Homer’s epic poem sulking in his tent, while his fellow warriors lay siege to Troy. Only when his best friend (and, it is heavily inferred, lover) Patroclus is killed while wearing Achilles’ own armor does he rejoin the fray. Slaying the Trojan champion Hector, Achilles dishonours his corpse by dragging it behind a chariot, before the Greek meets his own death at the hands of the Trojan prince Paris, who fires an arrow into the one part of his body that does not enjoy magical protection: his heel.

In this lithographic print, the seminal artist and L.A. punk scene legend Raymond Pettibon recasts Achilles as a mid-century cartoon pin-up, of the type seen in the famous 1950s ads for the bodybuilder Charles Atlas’s ‘Dynamic Tension’ method, which promised to transform a “97-pound weakling” into the “hero of the beach”. What Pettibon is gesturing to, here, is not only the role of Classical archetypes in brokering millennia-later models of masculinity, but also to these archetypes’ latent homoeroticism, and the hidden vulnerability at the core of even the most belligerent of men. There’s a reason, after all, that this Achilles’ protective shield is so much bigger than his (dainty, almost toy-sized) sword.

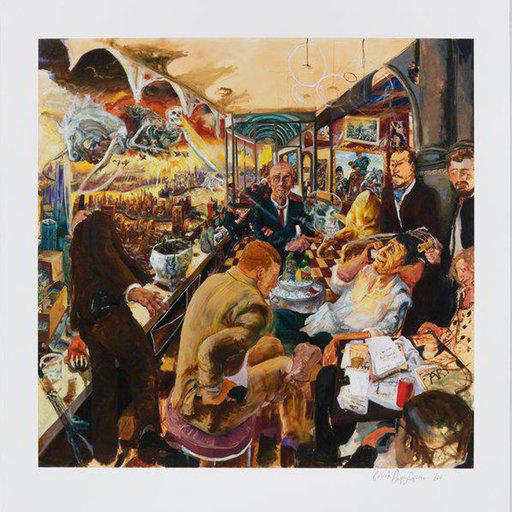

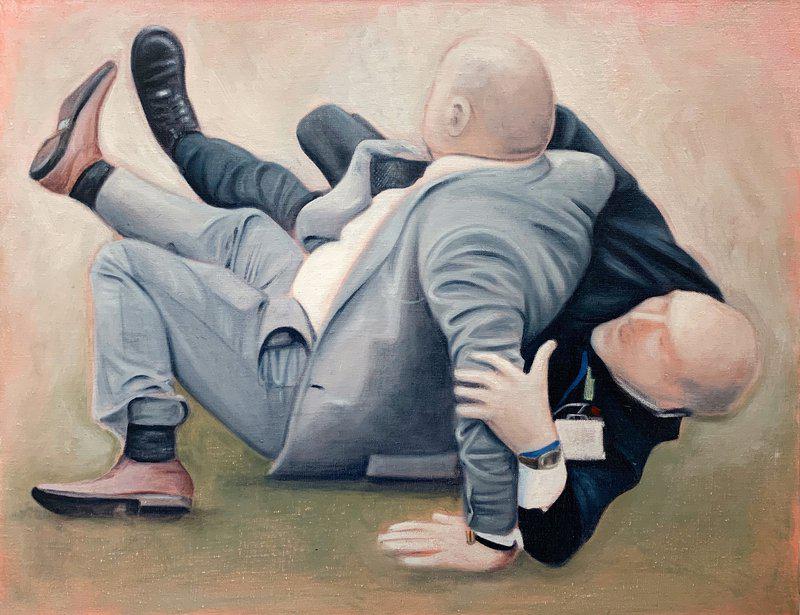

LYDIA BLAKELY - Hercules, 2019

Despite the romantic visions propagated by bridal magazines, the typical British wedding reception often has more in common with Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings of peasant matrimonial feasts than anything you might find in the pages of Jane Austen. A groomsman in a hired suit snogging a bridesmaid behind the bins? Check. The DJ breaking off an Ed Sheeran track to make an announcement about a badly parked SUV? Ditto. And then there’s this classic scenario, depicted in a painting by the rising British artist Lydia Blakely: two bald, pugnacious uncles coming to blows over some simmering family feud, having been on the prosecco since 11am.

Why has Blakely chosen the title Hercules for such a low-rent dust-up? With their pasty skin and chubby waistlines, neither of these men resemble the bronze, muscular demi-god of Greco-Roman myth. Like the 18th-century satirical poet Alexander Pope, that great practitioner of the ‘mock-heroic’ form, the artist employs Classical allusions to point to the discrepancy between fantasy and reality. Hercules may have been rewarded for his earthly labours with a berth on Olympus. The best these guys can hope for is a sweaty bed in a flea pit hotel - or a night in the cells.