‘Lubaina Himid’s paintings act as stages, inviting us into different worlds. She presents us with characters who are in the midst of difficult negotiations in their own lives. We are able to witness moments that are simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary, where cycles of tension from the past are still felt, where people are compelled to build and retain intimate relationships, despite the unknown.’ This summary is found in the exhibition catalogue accompanying Lubaina Himid’s current theatrical exhibition at Tate Modern and summarises the ideas and moments that repeatedly appear throughout her work.

Now 67-years-old, Himid is long overdue a full-scale museum show of this order. Born in Zanzibar to a white English mother and black African father, in 2017 she became the first black woman to win the Turner prize. She had moved to England as a child, following her father’s early death; migration, journeys and the lost islands of the past have become a recurrent motif in her work.

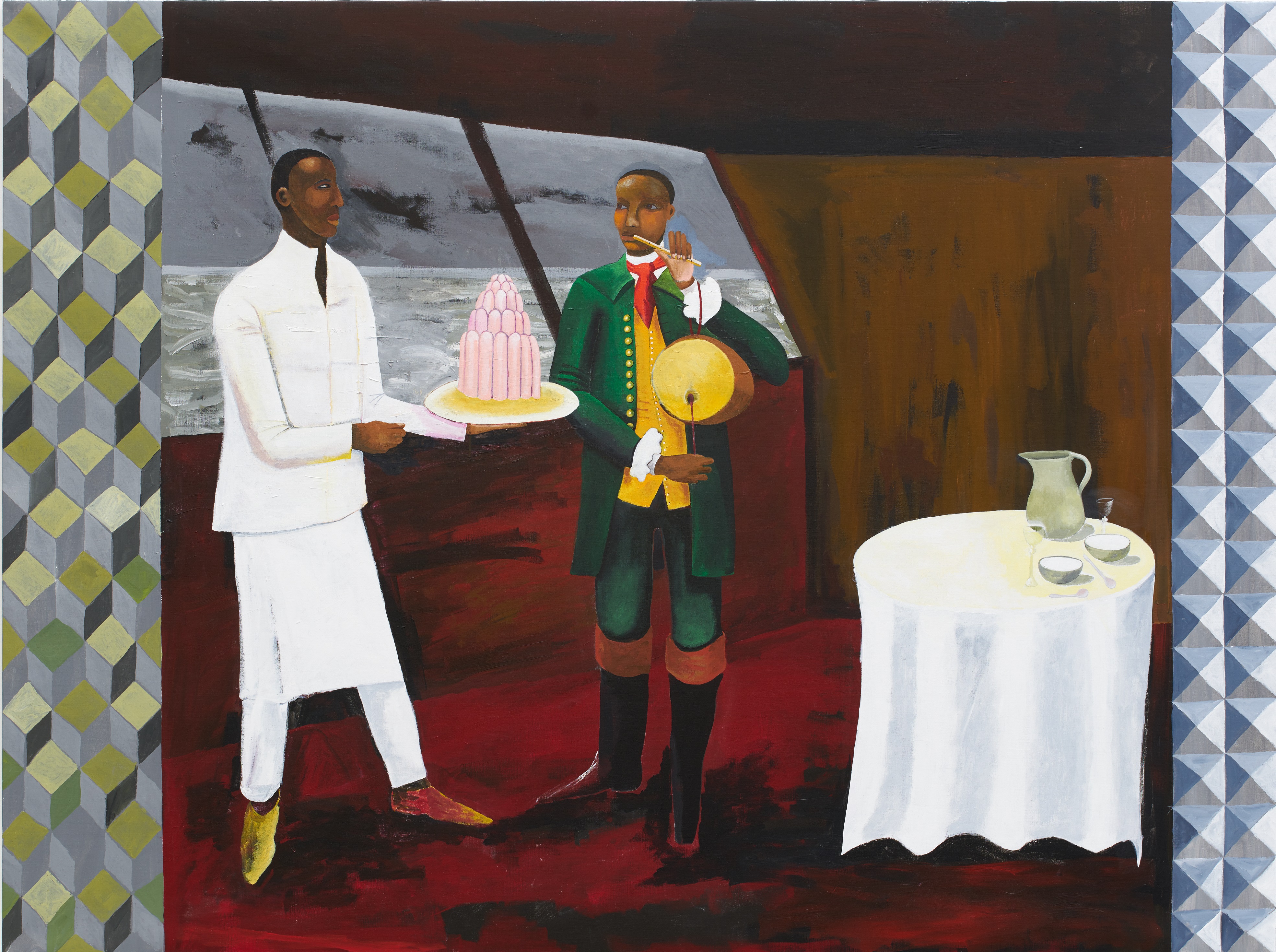

Le Rodeur: The Lock, 2016, Acrylic paint on canvas - Private collection, London

Le Rodeur: The Lock, 2016, Acrylic paint on canvas - Private collection, London

The retrospective takes over a floor of the Tate’s Blavatnik building. Rather than the staid formality of a standard retrospective, viewers are invited to walk through much of the work. Himid has brought together banners, installations, bus shelters, wooden carts, life size paper cut-out figures and a constantly audible soundtrack. To look at her work is to sink into it.

This is particularly true with her painting from 2017, Le Rodeur: The Pulley . This was one of a series of Rodeur paintings that Himid produced between 2016 and 2017, referencing the French slave ship of the same name. At first glance, it depicts an off-kilter domestic scene – two women face away from each other in what may be an upscale garden. There’s a class differential between them – one wears heels and stands idle by a chaise longue; the other, in flats and a working coat, moves the kind of chair in which you would rest an invalid. But their world is narrowly constrained. Beyond the tightly drawn borders of their placid existence moves a churning, inky sea, while the pulley above them holds a murky dark flag festooned with seashells. Something ominous moves behind and beneath them, even while they studiously ignore it.

Le Rodeur: The Cabin, 2017, Acrylic paint on canvas - Museum Ludwig, Cologne/Acquisition 2017

Le Rodeur: The Cabin, 2017, Acrylic paint on canvas - Museum Ludwig, Cologne/Acquisition 2017

Even by the standards of slave transportation, the story of Le Rodeur that inspired this painting is particularly grim. In April 1819, while the ship was traveling to Guadeloupe from The Bight of Biafra, 162 of the captive men women and children on board went blind, most likely from opthalmia (a bacterial infection which causes inflammation and swelling of the eye). In order to claim the insurance, the captain had 36 of these people thrown overboard. In time, all the slaves, but also the crew went blind, oppressor and oppressed sharing the same fate.

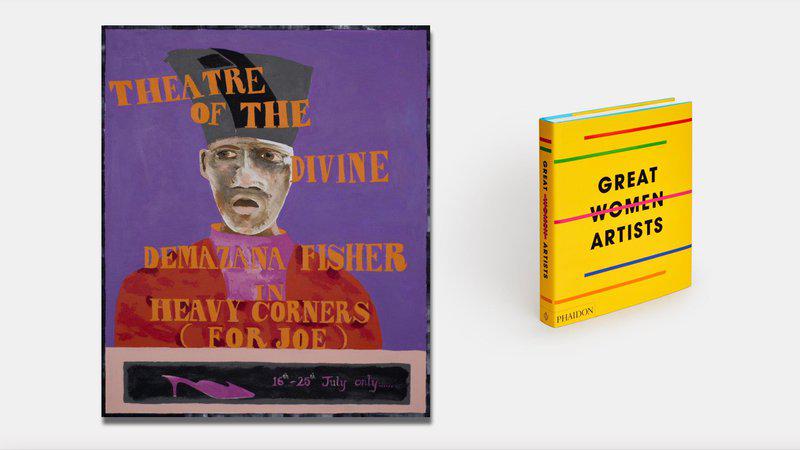

Lubaina Himid - Theatre of the Divine, 2019 - Available to buy on Artspace now

Lubaina Himid - Theatre of the Divine, 2019 - Available to buy on Artspace now

In this painting, as in the others in the series, the lives of these enslaved people – and the future lives they never got to lead – are relocated in the present. In all of them, the sea remains a constantly visible presence – the location of the original atrocity. And while the banal, colorful world of modernity has excluded the chaos of the water, it still roars around these people. And in this particular painting, the central pool – shaped and placed like a trap or a danger in the center of the floor – gives it an even stronger presence. These people may have left the water, but the water has not left them. The (London) Observer’s review talked of the power of the story told by Le Rodeur – ‘deathless mythologies of departure and arrival, so graphic in their facture, so enigmatic in their legends of voyage and loss.’

Le Rodeur: The Exchange, 2016, Acrylic paint on canvas - Courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

Le Rodeur: The Exchange, 2016, Acrylic paint on canvas - Courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

This shifting of the boundary between inside and outside is not the only technique that gives Le Rodeur its depth and draws in the viewer’s eye. Different tones of the same color repeat across the image like a fading echo: the yellow moves from the murky, soup-like shade of the floor to the luminous buttercup yellow of one woman’s coat; the deep purple of the chaise longue is repeated in the pale lilac of her trousers; the blue of the pool that has a chlorinated, synthetic quality, contrasts with the violent navy of the clouded sky. And diagonally across the scene runs a long column of translucent, geometric shapes. These kinds of patterns crop up throughout Himid’s work – in the intricate fabric of the subjects clothing in Bittersweet (2021) or the technicolor flag lines cutting across the top of the fame in 2018’s Ball on Shipboard.

Le Rodeur: The Pulley, 2017, Acrylic paint on canvas - UK Government Art Collection

‘No issue, series of events, or time in history is ever simple,’ said Himid in an interview with the American art historian and curator Zoé Whitley for Art Basel. ‘I’m often talking about narratives where a gap needs filling in an enormous history. The device of six or nine works involves shifting emphasis with each piece in the series. There are now six Le Rodeur paintings, which are, in a sense, giving an opportunity to watch a drama unfold.’ She described how the contrast in the painting, between domesticity and wild nature, past and present, normality and atrocity, is an eternal question contained in her art. ‘I keep trying to get to the bottom of this question of how much past historical trauma is vibrating around, say, the buildings that were built with the wealth of that time. That atmosphere lingers. What does it do to us as protagonists within those spaces?'

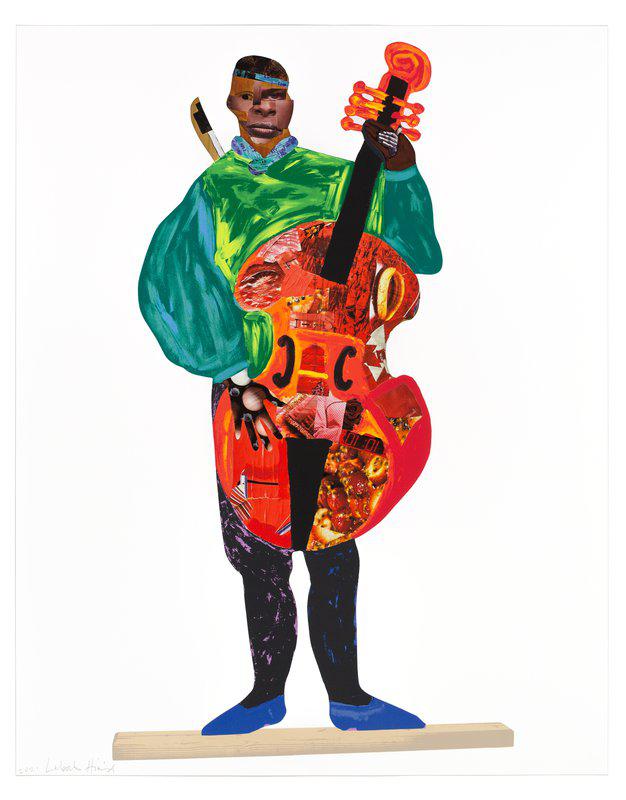

Lubaina Himid - Naming the Money: Kwesi, 2004/2021, 2021- Avavilable to buy on Artspace now

Lubaina Himid - Naming the Money: Kwesi, 2004/2021, 2021- Avavilable to buy on Artspace now