“Thousands have lived without love, not one without water”. This is the concluding line of WH Auden’s 1957 poem First Things First, and his point is inarguable. Without H2O, terrestrial life would be a non-starter: it covers some 71% of the earth’s surface, and makes up 60% of the human body. Far more than gold or oil, it is our planet’s most precious resource, and for all its local abundance, is a rare one in the endless, empty cosmos. Should the Earth’s waters run dry, our nearest supply is on Jupiter’s moon, Europa, which astronomers believe conceals a warm ocean beneath its icy, craggy crust.

But if water is a precondition of life, and connotes purity and even holiness in cultures across the globe, it is also a source of danger: think drowning, contamination, and our ever-rising seas. Perhaps this dichotomy is why so many great artists have found themselves drawn to H2O, from Hokusai ’s iconic woodblock print The Great Wave Off Kanagawa (1847) to JMW Turner’s hellish seascape The Slave Ship (1840), from David Hockney ’s poolside study of stillness and motion A Bigger Splash (1967) to Yoko Ono ’s performance poem Water Talk (1967), in which she delivered the lines: “you are water / I’m water/ we’re all water in different containers / that is why it is so easy for us to meet / someday we’ll evaporate together”.

Here, we bring together six works by contemporary artists that explore H20 as a source of wonder and terror, an element that speaks of both playfulness and threat, and above all of ambiguity. As the Daoist sage Lao Tzu had it, “Nothing is softer or more flexible than water, yet nothing can resist it”. Like time, all we can do is watch it flow.

A champion ice skater turned celebrated British artist, Ruth Proctor creates performances and actions in which ephemeral and near-intangible ‘materials’ (among them light, wind, smoke, and water) articulate time, space and place. When more concrete objects appear in her works, they are neither isolated nor static, but are rather corralled and buffeted by forces beyond their control. Take her 2015 live event Public Fountain Hat Dance, in which she attempted to balance a black bowler atop a vertical jet of water in the courtyard of London’s Somerset House, a feat which met with at best temporary success. When the pressure of the jet changed, the inanimate, insensible hat – unable to respond to its pluming “dance partner” – lost its equilibrium, and was sent spinning wetly through the air.

Poised between drama and slapstick, Proctor’s stunning documentary photograph captures the precise moment the jet spouted higher, and the bowler was upended. Is this image about failure, or incommensurability, or is it perhaps about the nature of performance itself? Put liquid under just the right pressure, and it can play the part of a solid, supporting a hat as surely as a circus plate-spinner’s poles support rotating crockery. Tweak the parameters however, slow or quicken the fountain’s pumps, and the “dance” comes to an end. All we’re left with is a soggy black hat.

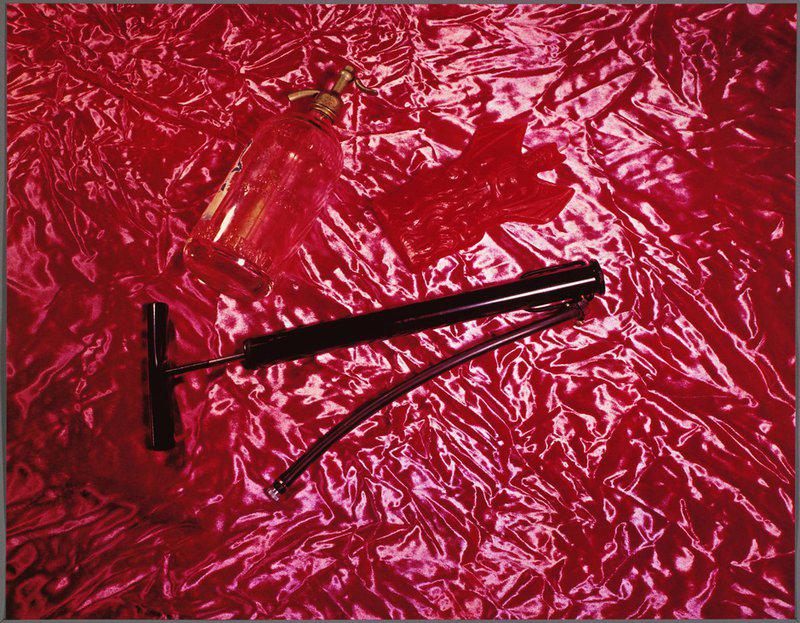

ED RUSCHA - Air Fire Water, from the Tropical Fish Series, 1975

Very few living American artists are as iconic as Ed Ruscha , who since the 1960s has produced a formidable body of paintings, prints, drawings, and photographic and film works that explore the intersection of the pictorial (most commonly images of SoCal Americana, including gas stations, billboards and huge, flaming skies) and the textual (phrases or single words that hint at obscured narratives, such as “COLD BEER BEAUTIFUL GIRLS”, “THE MUSIC FROM THE BALCONIES WAS OVERLAID BY THE NOISE OF SPORADIC ACTS OF VIOLENCE” and simply “The End”). This is Pop at its most deadpan, and its most gnomic. As Ruscha has said: “Art has to be something that makes you scratch you head”.

In this 1975 photographic print, Ruscha has gathered together a trio of objects – a bike pump, a soda siphon and a kitschy red plastic statue of a demon – which correspond to three of the four Classical elements, respectively air, water and fire. Looking at these man-made objects, it feels as though they represent the domestication – and hence the diminution – of powerful natural forces: winds, floods, raging blazes. To what use have they been put, on these rumpled, roseate bedsheets? A ritual, a sex game? And where, for that matter, is the object representing the fourth element, earth? Characteristically, Ruscha leaves it for the viewer to tease out meaning, here. After all, as the artist has commented, “Good art should elicit a response of ‘Huh? Wow!’ as opposed to ‘Wow! Huh?’”.

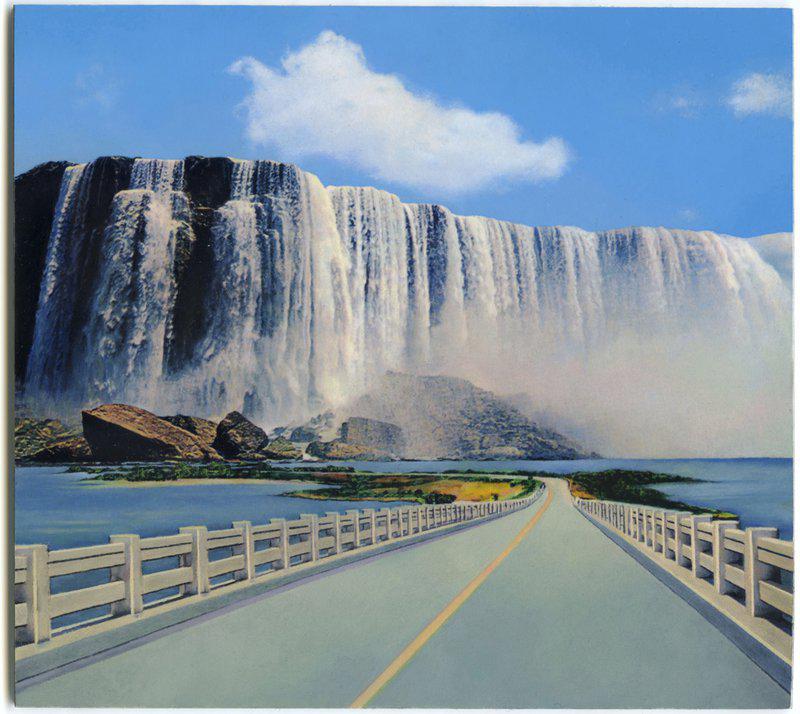

RON WEIS - Wish You Were Here (Waterfall), 2014

While this meticulously rendered Photorealist painting by the noted American artist Ron Weis is barely the size of a postcard, it is nevertheless a vision of the Romantic sublime, in the tradition of the vast, light-strafed vistas captured by exponents of the 19th-century Hudson River School such as Alfred Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church. In the foreground, a road snakes along a land bridge bisecting a still blue lake, towards a thundering waterfall of such gargantuan size that it cannot be contained in the image’s frame. Whatever awaits us at the end of this road – a deep understanding of Nature’s awesome power, a café and a gift shop – is obscured by spume and mist. In any event, this is clearly a sight to tick off the bucket list, hence Weis’ (gently sardonic) title. What a pity, then, that this landscape is the artist’s invention, and these falls exist as nothing more than an arrangement of pigments.

The poet William Wordsworth described the experience of the sublime as one in which the mind attempts to grasp something (the magnitude of a mountain, say) “towards which it can make approaches but which it is incapable of attaining”. Is Weis’ pocket-sized painting intended to deflate such Romantic thinking? It certainly speaks to an age in which countless Instagram feeds hum with near-identical #nofilter images of famous natural vistas, captured on planet-eroding “journeys of a lifetime”. And yet, the artist’s invented landscape also recalls the words of that semina 19th-century proto-environmentalist Henry David Thoreau: “Nature is not made after such a fashion as we would have her. We piously exaggerate her wonders, as the scenery around our home”.

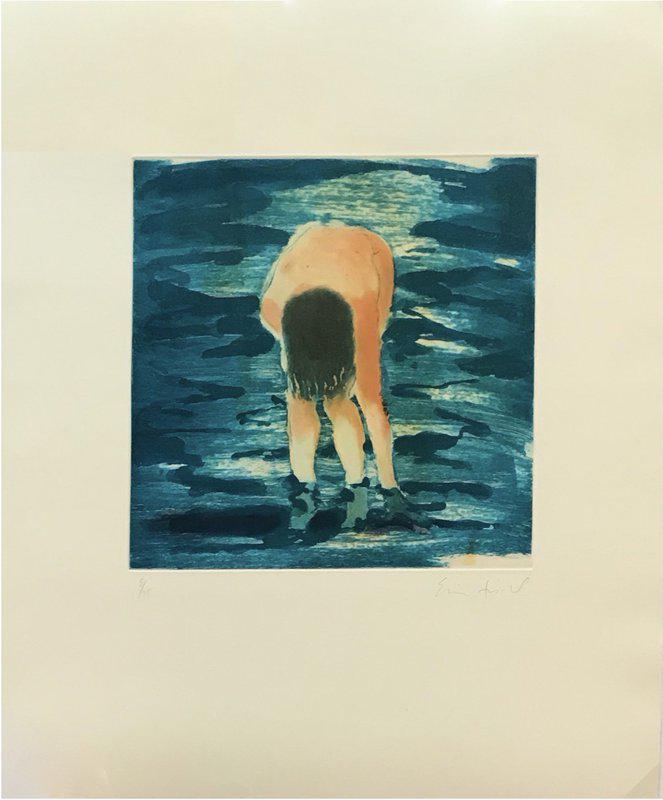

ERIC FISCHL - Untitled (Boy in blue water), 1988

“I tend to think of water as this element that is archetypal and symbolic. Water is the place we came from, both as a biological species through genetic evolution, and also in terms of the birth cycle. It has a lot of subconscious resonance to it”. So says the artist Eric Fischl, whose works chronicling the latent darkness of American suburbia feature in the collections of such major institutions as MoMA New York and MoCA Los Angeles. Perhaps his best-known painting, Sleepwalker (1979) depicts a nude, ginger-haired adolescent male masturbating into a kiddies’ paddling pool. Is this teen really a somnambulist, as Fischl’s title suggests, or is this an image of America “sleepwalking” into perversity, inured by habit to anything but its own self-satisfaction? Is suburban privilege simply the water in which the nation – or at least a certain, powerful portion of it – swims?

At first glance, Fischl’s print Untitled (Boy in blue water) , has little of Sleepwalker’s jolting candour. A nude child, or perhaps adolescent, stands ankle deep in a shallow pool or sea. Its face, chest and genitals obscured by a bent back and longish hair, this is a curiously androgynous figure, and we only have the word of the work’s title that this is a young male. We might wonder what his left hand is reaching for beneath the surface of the dark, dappled waters. Has he lost something (a pair of trunks, his childhood innocence?), or might he be attempting to merge with the liquid element that surrounds him, to become one with its fluid, amorphous state?

SASHA BEZZUBOV - Water 45, 2008

In March 2021, a team led by the Harvard planetary scientist Junjie Dong published a paper in the journal AGU Advances making an extraordinary claim: that between 2.5 and 4 billion years ago, the surface of the Earth was entirely covered in water. Adjusting for time period, this vision is, of course, not unknown to scripture, or to science fiction: witness the Biblical story of the deluge, or JG Ballard’s classic post-apocalyptic novel, The Drowned World (1962). Today, as humanity faces an unprecedented ecological crisis, in which sea levels are predicted to rise by at least 1 meter by 2300, flooding large parts of the planet, Dong’s paper might not only give us a glimpse of the Earth’s distant past, but of its near future, too.

The acclaimed American photographer Sasha Bezzubov ’s image Water 45 is, for all its austere, Vija Celmins -like beauty, a dispatch from the front line of the climate emergency. Shot on a large format camera in Arctic Alaska using a technique borrowed from the legendary mid-century photographer Ansel Adams , it depicts not the great white glaciers we associate with the region, but the black seas into which they have thawed, as a result of global heating. Cooling ice, here, has been transmuted into warming water, and dry land is nowhere to be seen. Where, we wonder, might humanity make a stand against its own worst instincts, when all solid ground has sunk beneath the dark, consuming waves?

ZHOU HONGBIN - Aquarium 23, 2014

“I, I wish you could swim / Like the dolphins, like dolphins can swim”. David Bowie ’s anthemic track 1977 “Heroes” wasn’t addressed to members of the mammalian Leporidae family, but looking at the leading Chinese artist Zhou Hongbin ’s strikingly joyful digital manipulated photograph Aquarium 23 , it appears that a warren’s worth of rabbits have nevertheless run – or indeed, swum – with the Thin White Duke’s words, swapping subterranean for subaqueous life. Sporting playfully in their tank, furry legs kicking, they have taken to their new surroundings like, well, fishes to water.

While Hongbin’s relocation of the bunnies from a dry to a liquid environment makes us look at these creatures anew, it also has the strange effect of making them more relatable. Humans, after all, are among the minority of land mammals who swim for fun (others include elephants, moose, and Kharai camels). Indeed, as exponents of the aquatic ape theory postulate, our species’ bipedalism, hairlessness, vaguely webbed fingers, fat distribution and relatively poor sense of smell points to a period in homo sapiens’ development when we spent much of our days in seas and rivers. According to this hypothesis, for us water was once not an alien element, but – as it is for Hongbin’s rabbits – our cherished second home.

To see and learn more about these prints and many more visit the Artspace archive here .