The 'lone genius' theory of artistic production is an unpopular one in an era of funky artistic collectives at one end of the gallery system, and blue-chip painters and sculptors working with a phalanx of fabricators, at the other extreme.

However, you only have to dip into a few interviews, archives, and biographical essays to realize that a lonely childhood, a preference for one’s own company, or the practice of going into the studio alone and not coming out until the work is done, remains a recurrent method of creation for many artists.

If you’re working from home, or even self-isolating at the moment, then maybe you can learn from the painters, sculptors and photographers who thrive, or have thrived, on solitude, and the occasional bout of attendant lonliness.

Haegue Yang - Cup Cosies, 2011

Cup Cosies

, 2011 by Haegue Yang

Cup Cosies

, 2011 by Haegue Yang

This Korean-born, sculptor and collagist and installation artist might be the toast of the international art fair and biennial circuit, but a strong streak of solitude lies at the center of her work. A February 2020 New York Times profile described how her art “often addresses themes of individual and national identity, displacement, isolation and community.”

“She is always working, and has spent her career deliberately isolating herself from friends and family as a kind of artistic method,” the article goes on. “The only downside is existential: ‘What comes along with the intensity of the work is you almost lose yourself,’ she said, although even this condition has its advantages: ‘I think the confusion is good to have.’”

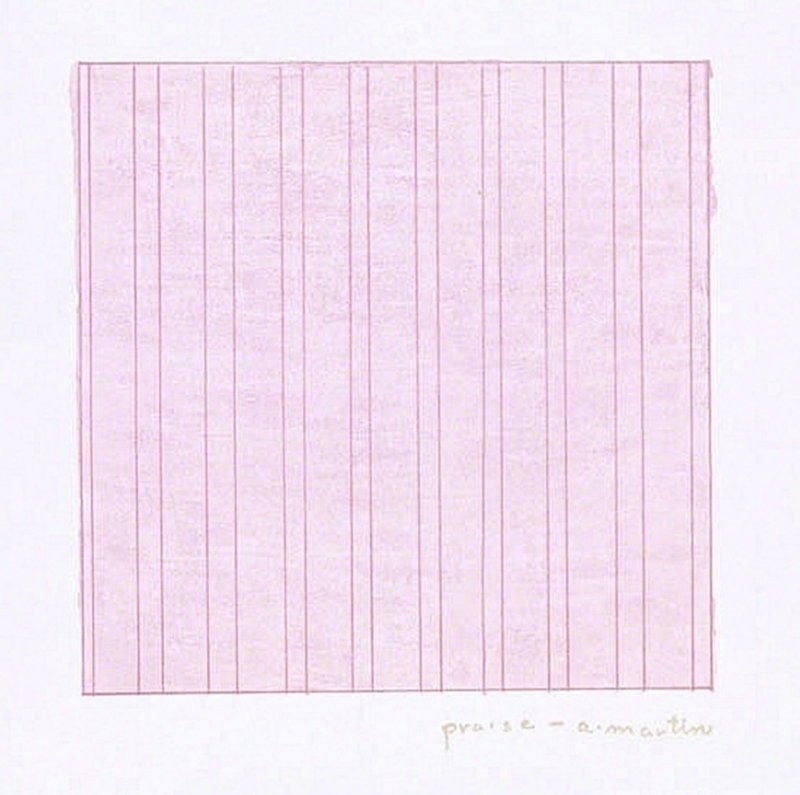

Praise

, 1976, by Agnes Martin

Praise

, 1976, by Agnes Martin

Once a New York resident, living in a loft on Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan (where her friends and neighbors included Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Indiana), Martin left town in 1967, and after some time on the road, settled in New Mexico, building her own adobe home, where she lived and worked alone, producing abstract works of remarkable simplicity, beauty and clarity.

Agnes’s long-standing friend and dealer, Pace’s Arne Glimcher, believes the lonesome life helped the painter overcome significant mental and artistic problems. “It was only solitude that got her painting again,” he told Phaidon.com back in 2015.

Alec Soth - Dallas City, II, 2002

Dallas City, IL

, 2002 by Alec Soth

Dallas City, IL

, 2002 by Alec Soth

Some of us wind up in a lonely working environment, but the Magnum photographer Alec Soth actively sought out a life free from social interactions. “The reason I wanted to become a photographer was to spend time alone,” he said in a recent interview. “The psychological elements of working alone are so profound.”

Unlike many of us, he wasn’t stuck in the house, but on the road. However, he still recognized the values, and dangers of the solitary life. “For me, being alone is really connected to travel,” Soth went on. “The benefits are that there’s no escape – you have to work, because what else are you going to do; how are you going to justify this behavior. I think the little tinge of madness that comes from spending too much time alone can be a good thing – you can access something real. But there many dangers as well, like being super-navel-gazing or pretentious.”

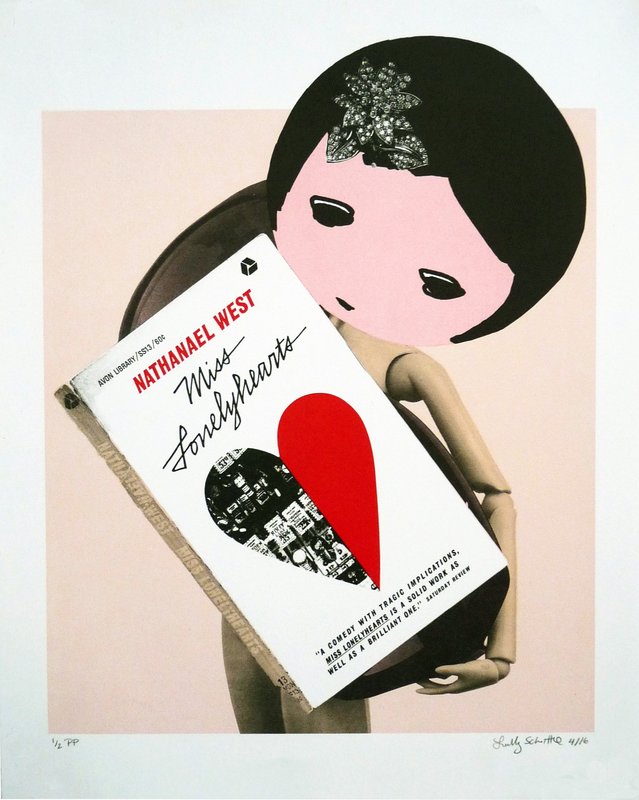

David Salle - Portrait with Scissors and Nightclub, 1998

Portrait with Scissors and Nightclub

, 1988, by David Salle

Portrait with Scissors and Nightclub

, 1988, by David Salle

Once the toast of the late eighties artworld, Salle doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who keeps himself far from the madding crowd. Not only a brilliant painter, but also a hugely talented critic and essayist, Salle nevertheless puts in the work on the canvas, on his own, in East Hampton, New York. “I still spend most days in my studio, alone, and whatever happens flows from that,” he has said.

And loneliness isn’t a marginal concern in Salle’s work. In a February 2017 interview in The Brooklyn Rail, he described how image making, particularly for his generation – which rose to prominence in the 1980s – directly keyed into feelings of isolation.

“Images in this culture work to edge you closer to the well of loneliness that we all live with; that is our inheritance in a way,” he said. “This is [critic] George Trow territory: the illusion of intimacy created by certain images. Their power is their ability to ameliorate and intensify loneliness at the same time. That was a big part of my early work, and also a number of other people.”

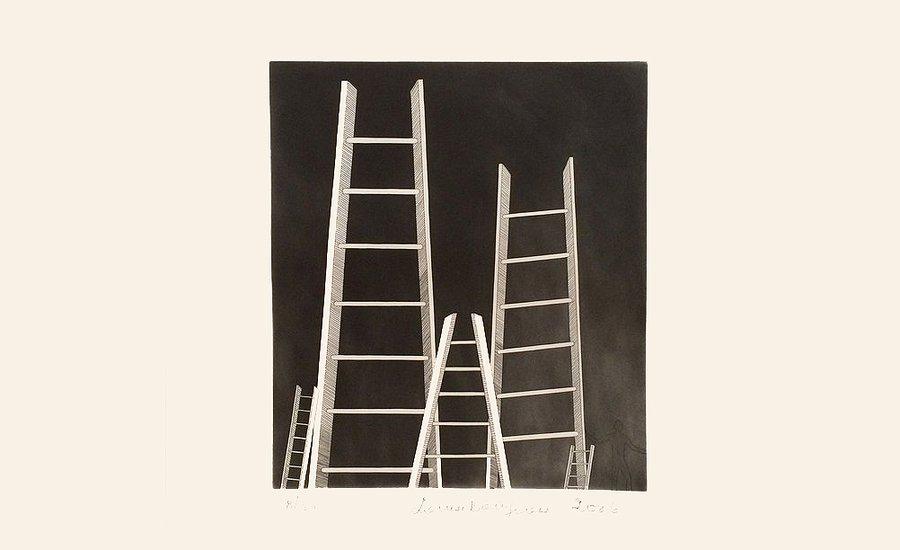

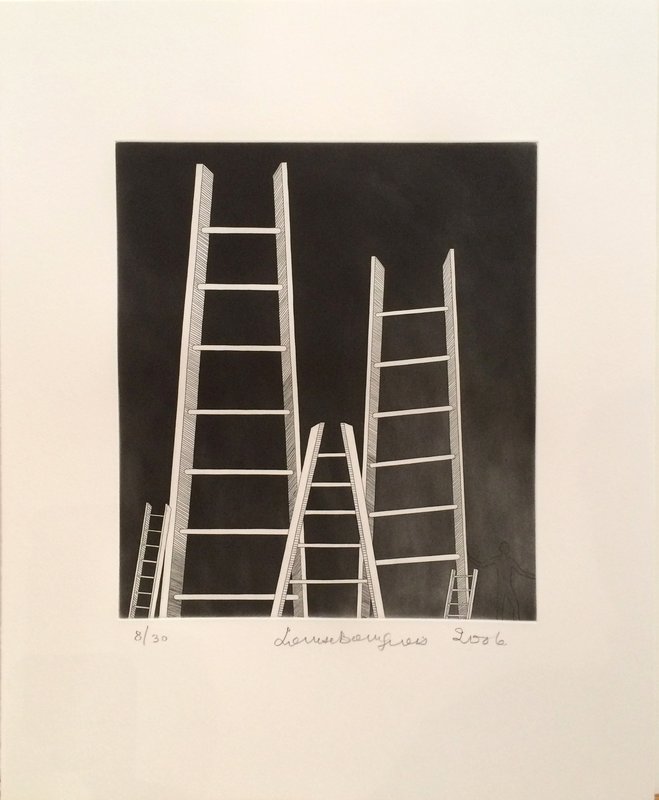

Louise Bourgeois - Ladders, 2006

Ladders

, 2006, by Louise Bourgeois

Ladders

, 2006, by Louise Bourgeois

While no one could accuse this French-American artist of being a loner - Bourgeois raised a family, maintained an active social life, and kept her singular artistic practice alive throughout her adult life - she also understood the importance of closing the door on everyone, when there was work to create.

“Solitude, even prolonged solitude, can only be of very great benefit,” she wrote in a letter to her college friend, the painter Colette Richarme, back in 1937. “Your work may well be more arduous than it was in the studio, but it will also be more personal.”

In a later letter she added, “solitude, a rest from responsibilities, and peace of mind will do you more good than the atmosphere of the studio and the conversations which, generally speaking, are a waste of time.”

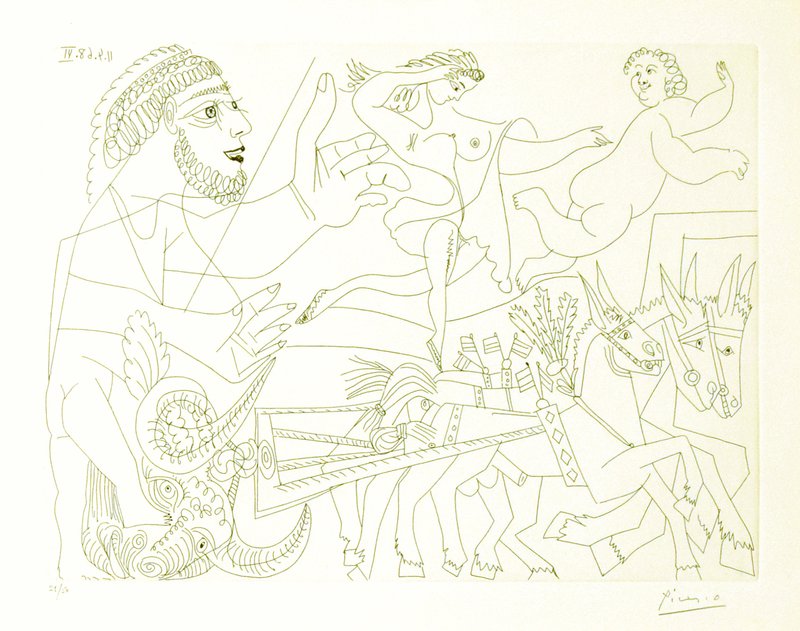

Pablo Picasso - Untitled, 11.4.68.VI, 1968

Untitled, 11.4.68.VI.

, 1968, by Pablo Picasso

Untitled, 11.4.68.VI.

, 1968, by Pablo Picasso

The greatest artist of the first half of the 20th century, Picasso was not only a genius when it came to painting, drawing and sculpture; he was also pretty good at the work-life balance.

“My grandfather was completely accessible only up until the moment he says 'Okay, it's time to work', when he closes the door and needs to be alone,” the artist’s grandson, Olivier Widmaier Picasso, recalled a few years ago. “Once he was in his studio, he was alone and no one could really enter that space.”

Indeed, Picasso’s own bodily presence was even checked at the door. “When I enter the studio, I leave my body at the door the way the Moslems leave their shoes when they enter the mosque,” the artist once remarked, “and I only allow my spirit to go in there and paint.”

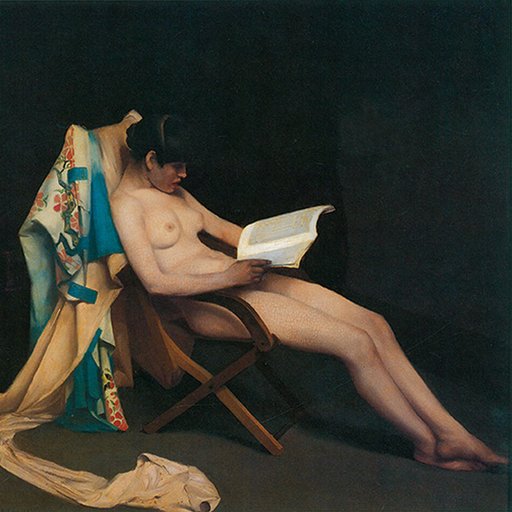

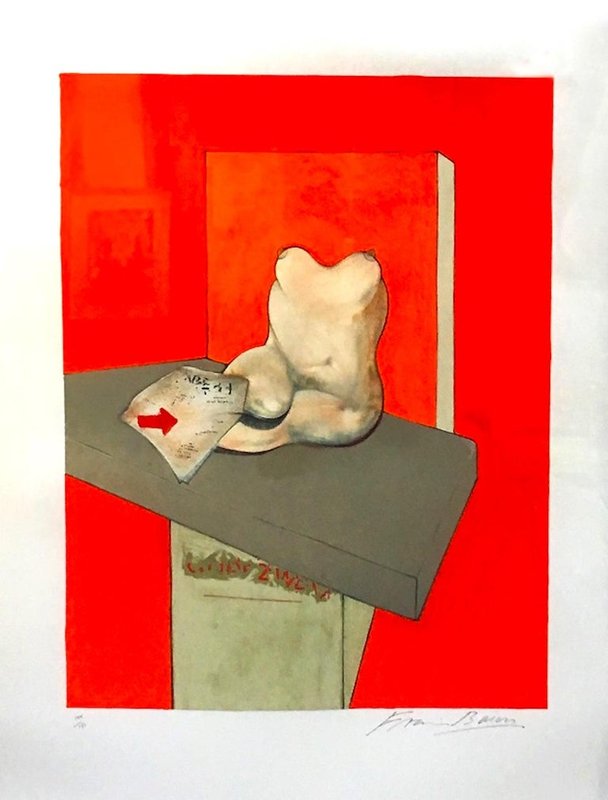

Francis Bacon - Étude Du Corps Humain D'après Ingres, 1984

Etude Du Corps Humain D'après Ingres

, 1984 by Francis Bacon

Etude Du Corps Humain D'après Ingres

, 1984 by Francis Bacon

Bacon’s childhood in Ireland was, by the artist’s own admission, both incredibly lonely and incredibly formative. “People frightened me,” Bacon said in an interview, conducted towards the end of his life, in the autumn of 1991. “I felt like I wasn't normal. The fact that I was asthmatic prevented me from going to school; I spent all my time with family and the priest who gave me my schooling. So, I didn't have any friends, I was very alone.

"I think I was unhappy as a child. I only ever had one view: that of emerging from it. Added to this was my shyness ... it was like an illness. It was unbearable. Later on, I thought that a shy old man is ridiculous, so I tried to change. But it didn't work.”

That sense of a social barrier continued into Bacon’s later life; the boxed off figures in his paintings have been likened to the ‘wretched glass capsule of the human individual’, as described in Friedrich Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy, a book beloved by Bacon. And, while he sometimes painted from life (as well as from photographs), Bacon asserted that “a painter is alone in front of his canvas; it's his imagination that creates.”

Again, from a critical point of view, that isolation is key. Writing in the LA Times at the time of Bacon’s 1985 retrospective, the critic William Wilson argued that “those big open backgrounds are theatrical in the same way as a small theater in the round. They are like a purposeful arena that tells us that that triptych about shaving, that homage to a stack of cigarette butts, that elegy on ghastly luggage, really does form the base of the drama of our absolutely isolated lives. Time and again, looking at Bacon brings to mind lines from T. S. Eliot, his ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas, his one-night cheap hotels.”

Ellsworth Kelly - Small Blue Curve 2012

Small Blue Curve

, 2012 by Ellsworth Kelly

Small Blue Curve

, 2012 by Ellsworth Kelly

Though his childhood was far less painful than Bacon’s, this American abstract artist was, according to the US art critic and historian, Eugene C. Goossen, “a ‘loner’ who did not talk early or very much and even had a mild stutter into his teens.”

Kelly also suffered from childhood illness, and credits his time alone with a certain mental outlook. “I felt a little bit outside my family,” he later recalled. “I’ve never been a family person at all, because it’s not very smart. You have to find yourself. Parents have their job, I suppose, but most of them are more interested in themselves and if they only let their children alone, some of them might have a few of their own ideas or go wild.”

Kelly certain came up with plenty of ideas, and remained a social distant through his working life. Speaking to Artspace in 2015, Kelly recalled his time in France immediately after World War II: “I didn’t speak French when I went there and I didn’t read it either, so I was very much a loner.”

"I liked being alone. I liked being a stranger,” the artist told the New York Times in a 1996 interview, when recalling that period. “I liked the silence.”

Even his work was somewhat divorced from any social commentary, and was meant to be contemplated simply for what it is, not as some greater symbol. “I think what we all want from art is a sense of fixity, a sense of opposing the chaos of daily living,” he told the Times in ‘96. “This is an illusion, of course. What I’ve tried to capture is the reality of flux, to keep art an open, incomplete situation, to get at the rapture of seeing.”

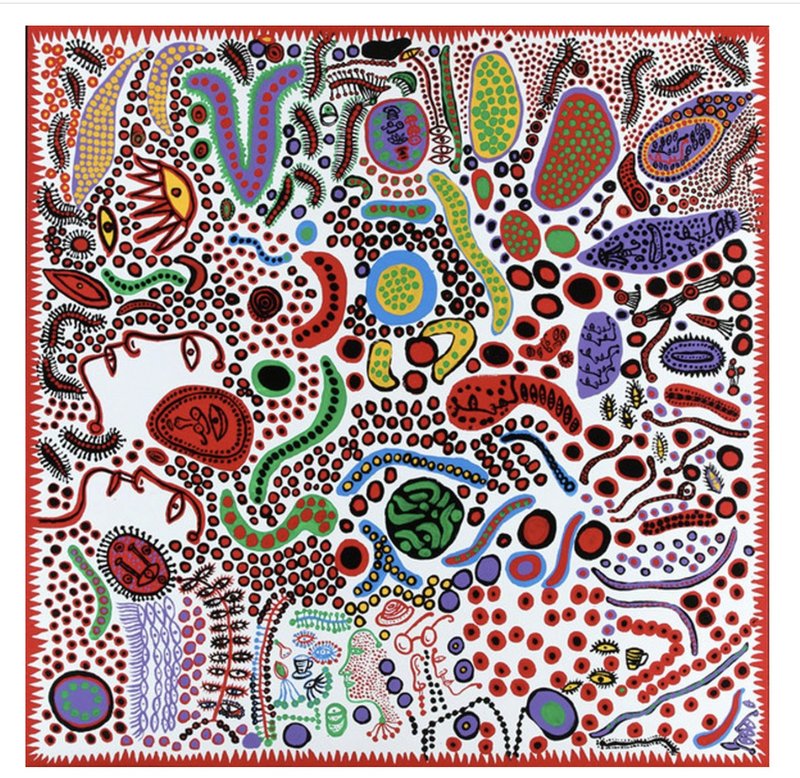

Yayoi Kusama - The Endless Life of People, 2010

The Endless Life of People

, 2010 by Yayoi Kusama

The Endless Life of People

, 2010 by Yayoi Kusama

Loneliness drives this nonagenarian Japanese artist, even if she doesn’t wholly relish the experience. “I am afraid of loneliness,” the artist told Damien Hirst in a 1998 interview. “I know I will be more lonely as I get older, but I can‘t tell at this moment how lonely I would be until I have actually become old.”

“I am very lonely being an artist, and in my own life. It is almost unbearable, especially when I hear the sound of tree leaves trembling in a wind storm. When I go up to the rooftop of a high-rise building, I feel an urge to die by jumping from it. My passion for art is what has prevented me from doing that.”

This might seem at odds with an artist who staged naked 'happenings' in New York during the 1960s and reached out to President Nixon in a letter. However, Kusama’s working practices today are quite different. She chooses to live in a Japanese mental health facility and “she prefers to remain in the solitude of her studio, enveloped by her work,” explained the critic Catherine Taft in a recent Phaidon monograph.

Other critics have picked up on this. In the catalogue to accompany the Hirshhorn Museum’s 2017 show Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, authors Mika Yoshitake, Melissa Chiu, Alexander Dumbadze, Alex Jones, Gloria Sutton, Miwako Tezuka, and Mika Yoshitake all examine Kusama’s “recurring themes of nature and fantasy, unity and isolation, obsession and detachment, life and death.”

Reviewing Kusama’s 2012 Tate Modern retrospective in the Financial Times, Jackie Wullschlager observed that, “Her isolation, at sea in a foreign art world, is poignantly suggested in an early immersive installation; Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show’ (1963), a salvaged rowboat and oars covered by white cotton phallic plaster castings and a pair of women’s shoes, set in a room lined with 999 black and white posters depicting the sculpture.

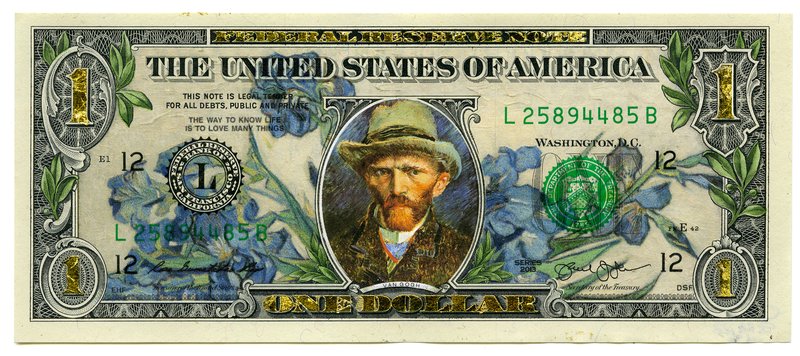

Donald & Era Farnsworth - Vincent van Gogh, 2017

Vincent Van Gogh, 2017

, by Donald & Era Farnsworth

Vincent Van Gogh, 2017

, by Donald & Era Farnsworth

Though Van Gogh enjoyed the company of fellow artists, his lack of success and mental health problems led to a life of great solitude. He did not actually relish a life alone. "I still hope not to work for myself alone. I believe in the absolute necessity of a new art of color, of drawing and – of the artistic life,” he wrote in a letter to his brother Teo in 1888 (the same year he cut off part of his ear). “And if we work in that faith, it seems to me that there’s a chance our hopes won’t be in vain."

While it is impossible to say with any great accuracy, we can at least posit that this loneliness both contributed to his singular works, and his eventual suicide. In a letter to his brother and sister-in-law brother, Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger, dated 10 July 1890 (just under three weeks before his death), he described a recent series of works: “they’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”

Certainly, those final years in Arles, southern France, saw Van Gogh’s artistic abilities peak, just as his mental faculties collapsed. “Alone in the sun-drenched fields and gaslit night cafés of Arles, he found his own palette of bright yellows and somber blues, gay geranium oranges and soft lilacs,” wrote the fellow painter, and critic Paul Trachtman, in the Smithsonian magazine. “His skies became yellow, pink and green, with violet stripes. He painted feverishly, "quick as lightning," he boasted. And then, just as he achieved a new mastery over brush and pigment, he lost control of his life."

[solitaryartists-module]