In the art world, known for its smug pretension and know-it-all elitism, an artist like Alicia McCarthy is a breath of fresh air. Born in 1969, McCarthy came up in the 1990s doing graffiti in the Bay Area. When she started being asked to show her work in galleries, she didn't see it as a way to rise up above her friends, she used it as an opportunity to bring them with her, often filling her shows with the work of her peers—now referred to as members of the Mission School movement (named after the area of San Francisco where they worked). The saying goes, "Nice guys finish last." McCarthy only quit her day job four or five years ago, when the market finally caught up to what she was going. (She now has shows under her belt at places like the Dallas Museum of Art, the Berkeley Art Center, and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and she's represented by Jack Hanley in New York.) For McCarthy, success means being able to spend more time in a (bigger and better) studio, but it also means being able to give back to the community McCarthy feels so connected to. The artist recently teamed up with Artspace to produce a limited edition to benefit the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive . ( You can collect the edition and support the fundraiser here. )

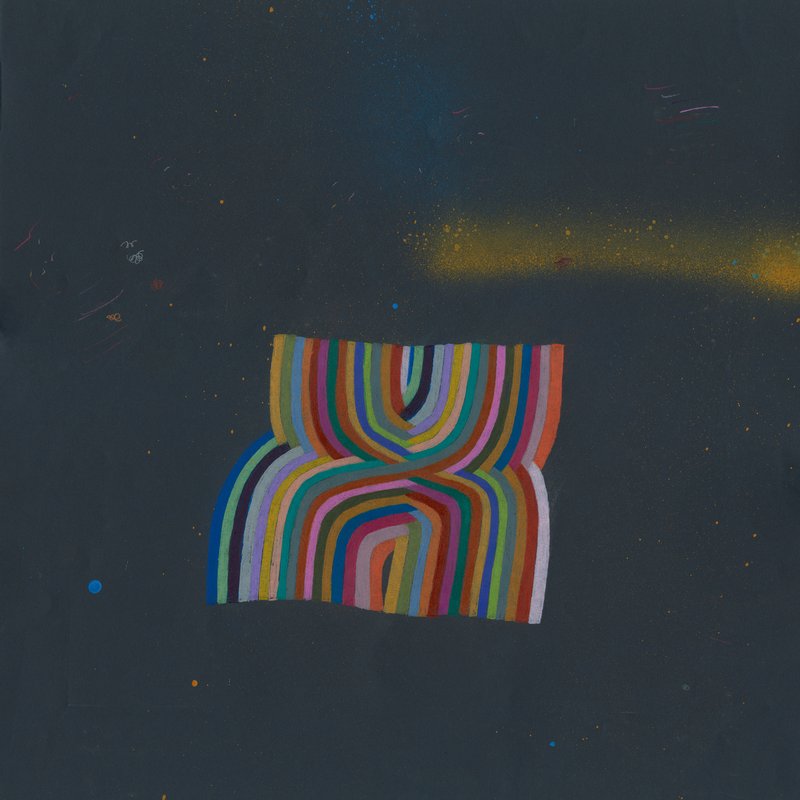

Alicia McCarthy,

Untitled

(2017) is available on Artspace for $750

Alicia McCarthy,

Untitled

(2017) is available on Artspace for $750

In the following conversation, McCarthy exhibits optimism and a little sarcasm, both of which can be seen on her canvases. She arranges her carefully chosen pallet of bright colors typically in the form of lines—sometimes criss-crossing one another in a woven, checker-like pattern, and at other times, following the arches of intersecting rainbows. The sarcasm, when there is any, enters her work sparingly in the form of minimal, straight-for-the-gut text. Whether her playful compositions are on the side of a train car, on a wall-sized canvas, or an 8 by 11 inch drawing, they always merge a DIY punk aesthetic and a folk naive sensibility.

Here, Artspace's editor-in-chief Loney Abrams speaks to McCarthy about the ways in which the artist uses her success to help out her community, about how the perception of graffiti has changed since she started, and about the edition she and Artspace produced to benefit the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

You started doing graffiti in the 1990s. How do you think the perception of street art has changed since you started?

I think the one thing that's changed is that graffiti is now commoditized. That really started in the '90s. I remember there was a commercial where someone had filmed some of Barry [McGee's ] work and put it in a commercial. That was epic at the time because the mayor [in San Francisco], Willie Brown, was one of the first people (in San Francisco, at least) who started really cracking down on graffiti and made a campaign about it. It was this two-fold thing where, on the one hand they were creating task forces to try to arrest more people, and on the other hand there were commercials that used graffiti spots. Everything changed after 9-11; people were getting federal offenses for urban terrorism. There's this notorious letter that Ruby and I got while we in school that threatened of kick us out of art school because we had painted all these farm animals all over the lockers. Now street art it's a really big part of the school there.

Right. You’re now featured as a notable alumni at the San Francisco Art Institute.

That's the hilarious part. I think the mentality shifted, sort of like it did around tattoos. Fifteen to 20 years ago, people thought that tattoos were for derelicts, but now that rich people and accepted people have tattoos, it’s different. So I don't know how much the graffiti has changed, but the attitude towards it has. For better or for worse (and I think both exist), it's being commoditized and accepted more in the mainstream as an actual skill and a form of creative expression. I can't lump all graffiti together because people do the same thing for all different reasons, and I can have an optimistic attitude and then I can have more of a cynical one—but I think it's something that's more accepted now on different levels as a creative form and a form of expression as opposed to vandalism.

I live near Bushwick in Brooklyn, where real estate developers use graffiti to brand their developments. In my coworker’s building for instance, the developers hired a graffiti artist not even to paint a mural, but to print out vinyl decals of graffiti art to put on the walls of each corridor on each floor. So each floor has identical “graffiti” print-outs. Meanwhile there are tour guides who give graffiti tours to tourists in Bushwick.

That's an amped up level of what was happening in the ‘90s with the first wave of yuppie gentrification, which came before hipster gentrification. It was the first wave of development where they'd have a cafe or restaurant and they'd intentionally leave the graffiti nearby so that you could see it but you're in your safe little space. I'm not in those spaces all that much but I know it exists, even in hotels, like the Wyatt. And it’s complicated, just like everything, as it all should be. I think people should get paid for what they do if that's in their moral code, for better and for worse and all in between...

Do you think young street artists who are just starting out can still be cool? Or are we passed the point when graffiti can be authentic and meaningful since it has become commoditized. Can you be cool and sell out at the same time?

I don't know... I think there have always been brats. There are people with integrity and people without integrity, so the ratio is probably the same as always, there's just more people out there doing it. I think it's interesting that now there are graffiti artists who are creating products to be sold to other graffiti artists and artists in general—since the use of spray paint in fine art is far more accepted and common than it was before. I still see tons of very exciting kids and people that are in their 30s who are making really incredible art in the street. My girlfriend’s nephew is 15 and goes to the local art school; he's picking up graffiti. I've always just seen graffiti as any other medium; there's a great discipline involved if you're truly dedicated to it. You learn from what you see and then you develop your own style and develop a community—that's another huge part of graffiti that I really love, it's very community oriented. But yeah, I think the ratios the same there's just more people out there doing it because of what I said before, that it’s become more mainstream.

Who are the younger street artists who you've been seeing around that you're excited about?

Piper, who writes “Spree.” She's hands-down one of the top Bay Area folks right now, along with her whole crew. Obviously Aaron Curry who wrote “ORFN,” too. He passed away a little over a year ago, but he was in his 40s and was very active on the street and had an international reputation, not that he went anywhere internationally. He was just a total diehard. There's another kid in his 20s who writes “Nevermind.” But I think Piper more than anybody. I'd seen her stuff on the street and then met her a couple years ago. She's a lifer. She paints and plays music too; she's a sickly talented person and is really one of the smartest people I know. That's really what it takes to do it for so long: you have to be really smart and genius and maintain a lifestyle. There's a lot of hard living in graffiti.

So do you still get on the street? When is the last time you tagged something?

I will tag on occasion, but it's for the younger people to do. Every once in a while Ruby [Neri] and I will be in New York and we'll have a friend who brings a bunch of stuff and we'll go out and be stupid in a way that we never would have before. But it's not part of my daily practice. One of the neater parts of knowing younger generations is that the influence goes both ways and the inspiration goes both ways. I think that's more about a lifestyle rather than necessarily whether you're out on the street or not.

You've talked a lot about community and I know that when you first started having solo shows at galleries, you’d invite other artists to be in them too. You bring your community with you. Was there any every discomfort in going from the street, where you had your crew, to the gallery, when you were on your own? Or was it a smooth transition from street to gallery?

I think both, honestly. So yes, there was and still is a discomfort and nervousness, especially during the last couple years where opportunities I've had are on a whole new level. I always feel like someone’s about to tap me on my shoulder while I’m installing to say, “No, this wasn’t what we had in mind…” I go into every show kind of freaked out and excited and I've learned to just get used to it and feed off of that energy. As far as the transition from street to gallery, I feel very lucky that the folks that I've worked with have let me do what I want. I think that’s probably because there's been some consistency in what I do. I like working with people at whatever level; I'm not in there to piss people off. I have a lot of respect for people who invite me into their home or their space, and I take it as a huge responsibility.

I don't think I’ve had any resistance in terms of wanting to bring other people’s work into the show. That started really early on when I was an undergrad. It wasn’t ever about me per se; it's more just about utilizing the space, and about being really proud to be a part of a group of people who are really incredibly, and wanting to show that. People are like, you're so generous! And I take issue with that because it's not about generosity. If anything it’s countering this idea of how value is created by isolating a few and eliminating a lot of people doing very similar things. I feel like I'm somebody who is... not a lost soul, but I feel very much like I'm part of the communities that I belong to. And if I have a solo show, those communities are part of it too. But it's not really that thought out. These are my thoughts about it now, thinking about it in the past.

Can you tell me a little bit about the edition that you're doing with Artspace? Is it a reproduction of a larger painting?

It's actually totally to scale. It's something I made specifically for this project and then I donated the actual drawing to the museum. To be asked to do something like this is something that’s pretty new for me. In this case, the edition benefits the Berkeley Art Museum so it felt better to me to do something original than to just do some reproduction.

Now your paintings sell for quite a bit of money. But in the beginning of your career, you were just making work to be seen, instead of making work to be sold. Do you see doing editions, which are more affordable than your paintings, as a way to get back to making your work more accessible to a wider audience?

Yes. It's also great because I can give them to people. And I still trade work with people, and I still try to make work that is small and affordable, or “affordable” in quotes. And yes, my work has very much increased in price. I see this as a wave that I have no control over and I'm going to work my ass off and enjoy it as much as possible but I have a plan B. I worked a full time job until four or five years ago and I'm not afraid or ashamed of going back to working a job if necessary.

But this is all very new. I'm not doing it for the money; I never have and I never will. I've spent so many decades doing this stuff for free that, in a way, being paid feels just like a bonus. But it's definitely nice to have money so that I can support other spaces, like the Berkeley Art Museum. If that can happen, if people actually do buy the edition, than that's great. I've actually purchased three of my friend’s work that I really like—so it's great to be able to do that, and to give to up-and-coming artist collectives and artist-run spaces in Oakland. And I also have the opportunity now to participate in things and then say, “I don't need the fee.” I can say, “No, you keep it.” And it also allows me to work larger and to afford a larger studio space, which helps the work. The work is never going to stop, it's not dependent on the money—but I'd be lying if I said it didn't affect it.

What was your full time job?

I worked at the roastery for Blue Bottle, which ironically is at the end of the block from where my new studio is now.

As an artist myself, it's almost comforting for me to hear another artist talk about their day job. There’s this double standard in the art world, where artists are expected to endure the “starving artist” cliché, and at the same time, it’s almost taboo for artists to admit that they need to work for a living. People don’t want to hear that an artist has a day job. It's a hidden conversation from the art world.

I wonder if it is more so on the east coast. I actually think that for the majority of people, getting a job and still keeping your practice makes you have a deeper connection to your work and more confidence in what you're doing. I work part time teaching in the art shools and I always tell my students this. I say, “Put your head down, get a job, make your work wherever possible, go to openings, find a gallery that you think your work fits into and set some… not goals, but expectations—or otherwise your going to be devastated by defeat,” to be honest. I think it's important to talk about this because twenty years ago the stigma was ten times worse. If you were an artist who worked in a gallery, nothing was going to happen to you. I don't find that so much anymore. There's a ton of people who have been art handlers or have worked in galleries or museums or as artists assistants, and those things are good opportunities. You can learn a lot from other people— a lot . Or you can work at Blue Bottle and feel bad about yourself, you know what you mean? I came from working parents who loved what they did and as time goes on I think that's played a role in my life. I've never have a hierarchy between a job verses a career; I think there's integrity in every action, or at least the potential for it.

Making a living is making a living.

Yeah. I mean, we're talking on a privileged level still, because some people don't even have the opportunity to think about what a career is. I mean, it's funny because I do see making art as a job but it's a job that I love. Even that is somehow controversial… People think that if you're an artist and you say it’s a job it's somehow belittling the art. But I take issue with people who think that art exists on some higher ground than everything else.

Speaking of making a living… The Bay Area has a history of supporting counterculture and artistic people, and now it's one of the most expensive places to live. How has that helped or hurt the art scene? Is it still possible to be a young emerging artist and still afford to live there? And on the flip side, has the art scene benefited at all from tech money?

I think it’s changing. This is my totally naïve, outsider opinion, but I think that the tech money people are slowly getting interested in art. They see it as a cool thing to be involved in, but also as a financial investment. I think there's a lot of effort to bridge these very different languages and ways of living between art and tech. Tech is going to do what you were talking about in the apartment building where they’re going to print graffiti on vinyl stickers. Are they going to buy the art? I don't know.

I can't deny though that someone I know moves to Los Angeles pretty much monthly. But I feel like there's still opportunities. It’s not like every undergrad or grad that I work with leaves right after school. There are still people out there banding together and opening artist-run galleries, which is another thing people are starting to look to more. There are still people making it happen. I don't sense that the art is changing but obviously less people are able to stay here than they were fifteen or twenty years ago. But I also think adversity creates reaction and it's a whole feeding cycle as well. Nothing comes easy and that's a good thing.