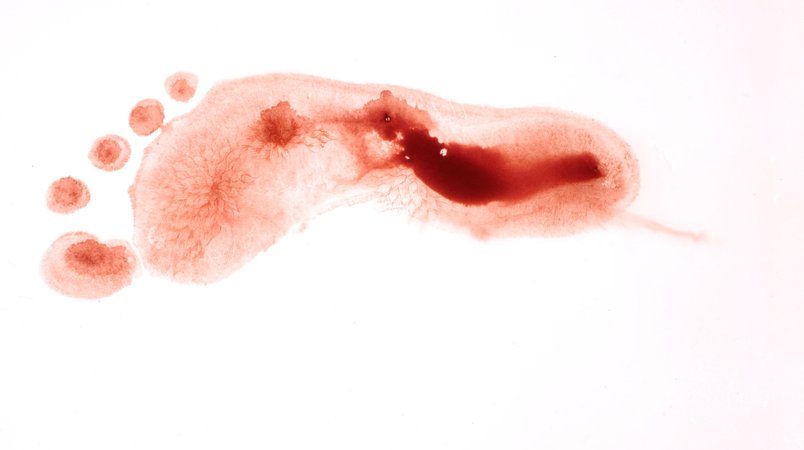

Perylene maroon paint is the exact shade of blood, and it’s the signature color of Pakistani artist Imran Qureshi, who spread it across the 8,000-square-foot terrace of the Metropolitan Museum of Art last summer and a courtyard in the Sharjah Biennial in 2011. Appearing at first like the site of a mass slaughter—a terrorist bombing, say, or a mall shoot-out—the red splatters, upon closer look, blossom with delicate foliage patterns carefully hand-painted by the artist. Qureshi's tiny deft strokes come from the traditional Indian and Persian style of 16th-century miniature painting and also evoke Arab calligraphy, together with a heady mixture of death, beauty, and rebirth.

Born in Hyderabad, Pakistan, in 1972, Qureshi was trained in the miniature tradition at the National College of Arts in Lahore, where he began infusing unorthodox elements into the this old art form: figures in bluejeans placed in ancient landscapes and broad, abstract strokes combined with patient, controlled lines. In 2013, he received Deutsche Bank's "Artist of the Year" award.

The month, Qureshi spoke to Artspace before the opening of his show at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University about how he reconciles the large and the small, the regional and the global, in his work.

The renowned Baghdad-born, London-based architect Zaha Hadid designed the Broad Art Museum’s austere aluminum and glass form. Does your artwork in the new show respond to this unconventional environment?

I’m a big fan of Zaha Hadid, and when I saw that space I thought it was so powerful that it became hard to imagine my old work just hanging there. I told [deputy director and curator Alison Gass] I wanted to do new works for this show, in response to this building.

What particular architectural elements were inspiring?

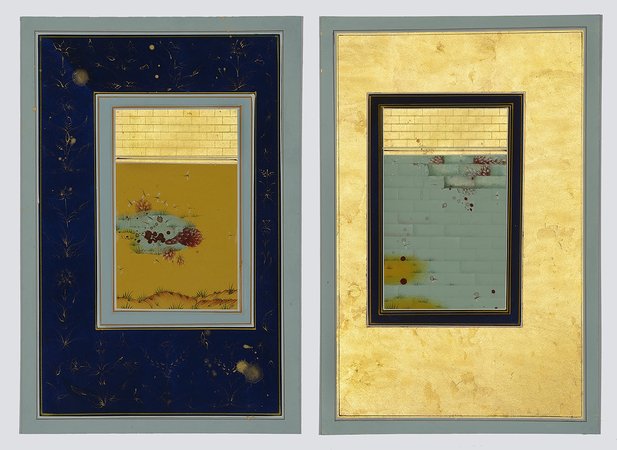

There is a huge window in the exhibition hall, and when I saw it, I thought that it looked like a manuscript of a miniature painting, like a book opening up. So I made a small miniature in the same format in response, creating a dialogue between the large, heavy, concrete metallic window with a very small work I made on paper with a water-based medium. It was a huge challenge to make my work speak in front of such a huge thing. And that was how the idea of the “God of Small Things” came in.

The window at the Broad Museum

The window at the Broad Museum

Is the title of the show an allusion to the book by the Indian novelist Arundhati Roy?

I love the title of that book, and I did a work in 2002 called God of Small Things, too. The idea of this very small organic form talking to that massive concrete form suddenly made me think of this title again.

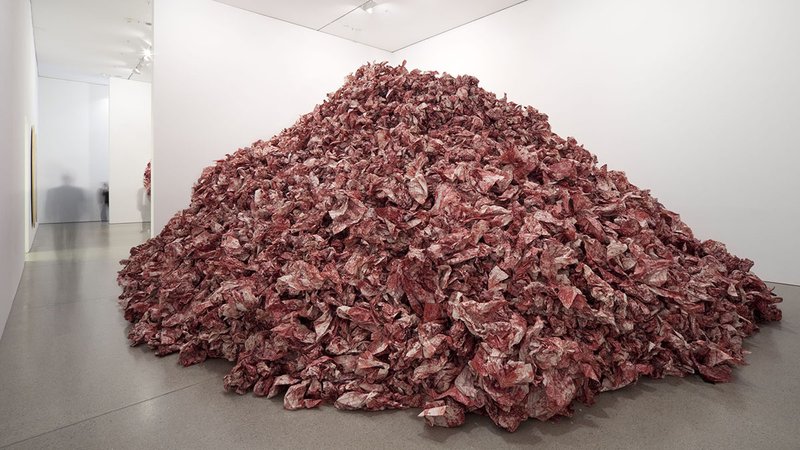

You also include 30,000 photographs of your Metropolitan Rooftop commission that have been crumbled into a huge pile, resembling a site of carnage.

There is a team of people who are contributing to making this work right now, and it makes an impressive sound in the hall as they crumble the paper. Of course, the visitor won’t experience this. But it's a very fragile medium, paper. The photographs are of the concrete rooftop covered with blood, and it becomes really messy and jarring—you see the concrete base on a paper medium, which is what I am working to reconcile. It is a very massive work. One of the walls is inclining on the opposite side of the artwork. So I am trying to create the effect of the paper pushing against the wall as this very fragile thing, but collectively it's very powerful.

It sounds like there are many kinds of dialectics at play in the show, between the large and small, the fragile and the sturdy, and also in subject matter of gory scenes depicted with exquisite organic forms, such as tiny flowers. Do these contradictory elements come into play in the two videos that are part of the show, too?

In my videos, I am trying to record the process of painting. The past couple of years, I have been using a lot of red color, and when the work is wet the paint moves across the paper and gives it another sort of life. It's so poetic. I really want people to catch that movement. So in both of my videos, I am trying to show the process of my painting to the viewer. The video is called It’s Still Moving, and the paint is slowly, slowly, slowly bleeding gradually across the screen.

Opening Word of this New Scripture, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Corvi-Mora, London.

Opening Word of this New Scripture, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Corvi-Mora, London.

Being so alert to your environments, do you think about your work differently in an American context—especially in a post-9/11 America—as compared to the rest of the world?

For me, violence is not strange to anyone in the world. Everyone is affected, though sometimes indirectly. So in that way, everyone has the same kind of reaction to the imagery. It's not about illustrating particular incidents—it's more than that. It's about painting exile, and that context is very global. It’s not specifically about my region.

But it sounds like there are different responses elicited in different regions. In Sharjah, you’ve said you remember people breaking into tears upon entering the bloodied courtyard. At the Met, it was a bit less somber, with people sipping wine amid panoramic views of Central Park—even though the rooftop is only miles away from where the Twin Towers once stood, and even though it opened days after the Boston Bombings.

Sharjah is the best example, because the people were not just from Sharajah, they were from all over the world, from America, from Europe, from Asia, from the Middle East. They all brought personal stories and personal experiences with them from where they’re from. And even in New York, I got so many emails from the visitors that connected to the work. They came again and again to the same installation, and it was very touching for me that people really felt what I was trying to say. Violence is part of the history of human beings. Take any era, there was violence.

And They Still Seek the Traces of Blood, 2013. View from “Imran Qureshi: Artist of the Year 2013” at Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Berlin. Courtesy the artist and Corvi-Mora, London. Photo: Mathias Schormann

And They Still Seek the Traces of Blood, 2013. View from “Imran Qureshi: Artist of the Year 2013” at Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Berlin. Courtesy the artist and Corvi-Mora, London. Photo: Mathias Schormann

But does it matter if you are at the heart of that violence or geographically removed?

Psychologically, everyone is struck by it. When you are inside the city or country where the act of violence has happened, everybody feels the echo of that incident. Even in my country, I have not seen any violence with my own eyes, but it comes through the news, it comes through the environment of the city and affects everybody.

Coming from the news and seeing these images secondhand can be a desensitizing experience, too, though. Do you want your work to re-stimulate that emotional response?

If you’ve see my work from 15 years ago, I was just painting whatever was affecting me. And you don’t find sharp lines between one body of work and another body of work. It is not a planned thing. I am doing what I want to do. I paint what I want to.

So there's no particular emotional response you want to incite in your viewers?

However they want to respond, they should respond. If the work is not creating a dialogue with the audience, for me it's a useless work. So I don’t have expectations from the audience. The only thing I enjoy is that people relate to it in all regions.

Still from video It's Still Moving

Still from video It's Still Moving

There are three ways you group your work: miniature paintings, abstract works, and site-specific installations. How do you approach an installation work versus a work on canvas?

People always ask how I jump from the monumental to the really tiny. And for me, it was very natural and very comfortable. Even at the National College of Arts in Lahore, I enjoyed that kind of shift between those two opposite mediums, because I was always trying to bring together two very opposing things, like scratches and very loose abstract marks. Every surface and space has challenges. The excitement for me is dealing with those challenges, and sorting through that. I love that process. In my content, I always have this idea of life and death in my work, so these are two opposite things. I enjoy having these two opposite things and making them work for me.