Called “the quintessential American designer” by the Washington Post, John Varvatos has built one of today’s most enduring men’s fashion brands with two simple rules: keep it simple, and stay true to your roots. And for Varvatos—who has also held top roles at Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein—those roots are in the Detroit punk scene.

To understand the evolution of the John Varvatos aesthetic—and to launch our new partnership with the fashion brand celebrating the intersection of art, fashion, music, and style—Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to the legendary designer about his career, why style trumps fashion any day, and the one album photo that started it all.

As one of the most successful men’s designers in America, you have been part of a fashion renaissance that has allowed guys to care about their clothes in public—and for the rest of the world to care as well. At the same time, you’ve often said that you’re less interested in fashion than you are in style. Can you explain a bit what you mean by that?

Fashion for me is more about the fashion business, I guess. It’s something that’s of the moment, and although we’re all intrigued by the whole fast-fashion thing, I really am much more interested in creating style that has a lasting tone to it, and clothes that helps guys build wardrobes where, 10 or 15 years from now, they can reach back into their closets and find a great jacket and love it again. I like clothes that feel like they have a heritage to them.

Also, when I think about men, I think about guys who carry themselves with great style in everything they do—not just their clothes, but the way they carry themselves through life. I grew up with those kinds of style icons, who were less about the fashion part and more about what they left behind when they left the room. What are people thinking? Not that they were wearing this or that jacket but, “Boy, he looked really great,” or really cool, or really confident, or really sexy. So, for me, that’s always been style.

Growing up in Detroit, who were those style icons who really gripped you, or whose attitude resonated with you?

It’s funny. I grew up in the Detroit music scene, and there were a couple components of it. There was the Motown component, which was very flamboyant and fun and crazy, and which of course wasn’t me as a young kid growing up. Then there was the British Invasion component of fashion and style. And then there was one little element that came out of the Detroit area, courtesy of a band called Iggy and the Stooges.

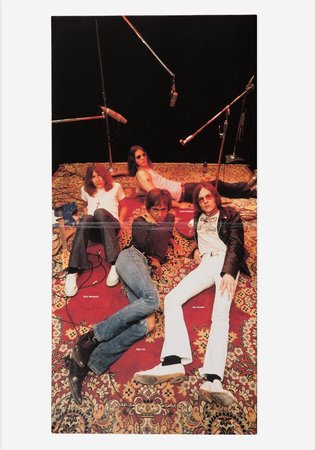

And it was pretty simple: the black motorcycle jackets, aviator glasses, skinny jeans—not beat-up Ramones jeans with holes but skinny, sexy jeans—and boots, not motorcycle boots but skinny boots. Every generation since then has fallen in love with that look. Every guy, every girl, has fallen in love with that look. And I remember when I first saw it, in 1970. The Stooges did an album called “Fun House,” and in the gatefold was a photo of them lying on a carpet. I just wanted to be those guys.

The "Fun House" gatefold cover

The "Fun House" gatefold cover

They do look pretty cool.

And that could be any band today. There’s nothing, other than maybe the little bellbottoms, that feels like dated. Graphic T-shirt, skinny leather jacket, tank top, the boots—and that shot is 46 years old.

The sneakers are the same, too.

Yeah, exactly. I wanted to be those guys, you know? I felt like I found my style when I found them, because the whole British Invasion thing was about this uniform where everybody was wearing the same jacket, like the Beatles did originally. Or it was velvet coats and flamboyance in that kind of way. But the Stooges look was my thing. That was something that I could connect to—it was simple, but there was a toughness to it, there was a sexiness to it. And, of course, I was 15-year-old kid when that album came out, so I didn’t know anything about sexy. Maybe I knew tough a little bit, but I didn’t really think in those terms—I just thought, “God, those guys are so cool. I wanna be those guys.” And, “Their music is so different from everything right now—I wanna be those guys.”

You mentioned how the British Invasion and Motown musicians both adopted a kind of uniform, which at times nodded to professional attire—suits and ties—and at times was flouncy and flamboyant. For the Stooges, what was the reference point for their style, the biker jackets and jeans?

Well, it’s kind of Marlon Brando with the biker jacket. If you ask Iggy—and I’ve spoken to him—he’ll say the same thing. But there’s also this grit of Detroit, this tough city. They weren’t dressing like a biker gang—because they don’t look like a biker gang, you know? But they had this tougher kind of blue-collar aspect. And if you go back to that period, you can search as much as you want but you won’t find another band that looked like them at the time.

So they were really the originators of that style, which has become the quintessential rock-and-roll look—the lingua franca for cool?

There wasn’t a band that dressed like them because rock and roll didn’t look like that back then. You didn’t see this kind of tougher style—at the time, they just seemed like the bad boys. Today, we look at it and we see it’s very sexy. And look at any band—say, Kings of Leon. They dress now like those guys did then.

You yourself dabbled in music for a while, playing the guitar. Were your parents supportive of your rock-and-roll lifestyle?

No.

Why not?

I grew up in a loving but very conservative family. My parents grew up that way, so they were that way. They didn’t really relate to my obsession with the whole music thing. But I was like any kid wanting to be rebellious, so the more they pushed one way, the more I pushed the other way.

How did you rebel? Did you join a band?

I was in a number of bands as a kid, and they were pretty okay with all of that. But I think they worried about where it would all go. They were thinking, “Is he going to do drugs?” I don’t know all the things that they worried about, but mainly they just didn’t think it would go anywhere. First of all, I wasn’t a good guitarist—I’m still not a good guitar player—so I wasn’t going to make a career out of it. It wasn’t like I was this prodigy. But music was a big part of my childhood. I grew up in a little, 900-square-foot home with eight people and one bathroom, and as much as I love my brothers and sisters, it was a very tight space. But when I put my headphones on, music took me into another zone—it transported me someplace else.

How did you become so drawn into the music scene’s style aspect?

The whole thing with style happened because I started following musicians as they played sets, and I would take pictures. As a kid, I wanted to be a photographer too, so I was just shooting people at concerts, or people on the streets, thinking, “I love this guy’s scarf.” “I love this boot.” “I love this woman’s whatever.” I’d go downtown Detroit and there’d be a protest going on, so I’d be taking pictures of people, everything, from their hair to the shoes—whatever was interesting to me. At the same time I started to create my own style out of all these things, because—with the exception of Iggy and the Stooges—I never wanted to look exactly like anybody. I love Keith Richards, for example, but I never wanted to look just like Keith Richards. So the music helped transport me to other places, and also to new ways of seeing the world.

What happened to these photographs? Do you still look back at them?

I had them for many years, but now most of them are really damaged. They were in slide form, and we had some water damage in the basement, so I lost a lot of it

At the same time you were immersing yourself in the Detroit music scene, you also made a side trip in 1979 to see a Ramones concert at New York’s CBGBs. While the Ramones had pretty straight-ahead rock style—with their leather jackets, jeans, and Converse sneakers—the punk wardrobe began to have a distinct style of its own, particularly after Richard Hell’s torn t-shirts started to influence the British bands. Soon, Viviane Westwood became the iconic fashion designer for the international punk style. What did you make of that look, with its torn garments and bondage elements?

That was a whole different thing, not what I grew up with, for sure. I got a kick out of it. It wasn’t anything that I connected with, or that I was going to wear, but I loved it. It was another way to rebel. Every generation finds their own voice in fashion, and in music, to rebel. They’re intertwined, they’re incestuous, and every generation figures out what their new voice is going to be. Rap is this generation’s voice, for instance. At that time it was punk, and it was a wave that was quite rebellious, and angry, too. Rock was never very angry, although it was very rebellious. And then came hardcore, and that was even angrier.

Punk was really about a lot of kids feeling like they were disenfranchised by society, and who were trying to carve out some kind of autonomy against their parents’ status quo.

No one wants to look like their parents. I mean, maybe there are a couple people who have the coolest parents on the planet, but I sure didn’t want to look like my parents.

So, when did your interest in style and your interest in music start to lead into the fashion business?

I guess it was in junior high school when, working jobs after school, I started to put together a little money to buy clothes, and I saw the effect it had with girls. So, I understood the rocker guys, and how they wanted to play rock music because it got girls. I never was that rocker guy, but I started to see that when I wore certain clothes that they wore, it made a connection with the girls. I was 14 years old, and I started becoming intrigued—like, “Wow, this is great. I’ve got to get some more of those clothes!”

So, I got a job at a clothing store then. First I was in the stockroom, then I worked my way up to selling, and so on and so forth. Over that period, I became more and more intrigued, and following things more deeply. We didn’t have the internet, so everything wasn’t instantaneous. Fashion wasn’t even a subject of any consequence, really, living in Detroit. Global fashion wasn’t something that people talked about.

So I started reading and looking at whatever I could find in magazines, sitting on the floor of a record store and going through every magazine, because I couldn’t buy them all. I’d buy one but I’d look through eight of them just to see everything. There weren’t necessarily fashion books or things like that at the time. It was really the music magazines that made me intrigued by the way people looked.

That seems like an epiphany: you don’t need be a musician to get the girls—you can just dress the part and cut the middle man, in a way.

I think you’re right, but I think my big discovery was just that style was important to girls, and maybe even more important to girls than to guys. Today, the world’s changed, but back then I would say it was more important to girls, how they looked at a guy. It wasn’t only a question of whether they liked his hair, if he good-looking, if he was tall, or whatever other things they were looking for. It was also a question of if he was cool. “He has great style,” you know?

In college, you studied education while continuing to work at clothing stores on the side to pay the bills. Then, a few years after graduation, you started your own men’s boutique with some friends in Grand Rapids, Michigan. How did that happen, and what was the concept behind Fitzgerald’s Men’s Store?

It was one of those things, like a lot of things in life, that just somehow happened. Right place, right time. I had married quite young, at 25, and my wife had the opportunity to move to Grand Rapids to work for a company, also in the fashion business. I though, “What the hell, let’s do it and just figure something out.” And when we got there, within days I met someone who owned a boutique shopping mall and was in talks to open a men’s store but didn’t have anybody to run it, to buy for it, to merchandise it, to do anything.

So I met the people involved, we liked each other, we formed a partnership, and we opened a store. It happened like that. It wasn’t like I was out pounding the pavement for a while—it really happened relatively quickly. It was a unique kind of store at the time, and we did a lot of interesting things, and my ex-partner still owns it under the same name with some other people.

At the time the store was starting out, you distinguished yourself by selling a brand that at the time was not widely available: Ralph Lauren.

Well, it was in a handful of multi-brand specialty stores around the country—there were no free-standing Polo shops yet—but we carried Ralph Lauren in the store in a very different way, in how we merchandized it. One day the president of Ralph Lauren, who was on a tour of stores around the country, came into our store and fell in love with that we were doing, and he told me, “If you ever wanna do something different, let us know. We’d love to have you work with us.” Within a year or so after that, I had some disagreements over the direction of the store, and so I ended up going to work with Ralph Lauren.

Why were you drawn to the brand, which represents what could be seen as the opposite of the rock lifestyle—a notion of refined, if rugged, landed American aristocracy?

It was completely different from who I was. But, then again, this was over 10 years after I first saw that Stooges image, so I’m a little more grown-up and need to have a business head as well. And I was intrigued by this guy who looked like nothing else at the time. I grow up in an area where preppy didn’t exist—I didn’t even know what the word “preppy” meant. I had never heard it before. When I went to work for Ralph Lauren, that’s how closed-in I was. But I was intrigued by his style. Everything from his philosophy to the way he marketed himself to him being this kind of cowboy, in a way. I saw pictures of him on his ranch and I thought, “This guy is a movie star,” because he wants to be a cowboy, he wants to be Fred Astaire.

It was a whole new brand universe.

Yeah, but I was intrigued more by the whole philosophy that you could be whatever you wanted to be. If you decide one day that you want to get up and dress like a gentleman landowner, as you termed it, or like Fred Astaire, you can put on this unbelievable three-piece suit and look gorgeous. I never thought about living all these different kinds of lives. Ralph creates dreams for people to be able to pursue.

Was rock and roll ever one of these dreams?

It was never a dream when I was there. Rock and roll never played the entire time I was at Ralph Lauren. It wasn’t in the thought process of the brand at all. I think maybe in the 21st century, it came into play a bit when other people came in with their smatterings of other styles. But when I was there it was always very much about the South of France, the Caribbean, the great American West, the Ivy League, the British. It was never rock and roll, ever, and I worked in design there a long time.

It seems remarkable that you came up the rungs of the fashion ladder from beginnings in retail. How did you pick up the craft of designing clothes yourself?

It was when I was working at Ralph. But the first thing I did there was I moved to Chicago and I took over the 10 states in the Midwest selling for him, overseeing those regional sales for the company. The company was small at the time but it was growing fast, and my territory was growing faster than ever. Eventually, they wanted me to come to New York to head up all sales for the company.

When I moved to New York I was 27 years old and I had one very young child, and I started getting very involved at the company. I took over the merchandising, and I was connecting with the designers every single day in the design studio at Ralph Lauren. I fell in love with it. The light bulb went off: “This is what I wanna do.” So I took a few classes to understand how to sketch better, and while I had already had some understanding of sewing because of heading the tailor shop in some of the stores I had worked at, I wanted to understand pattern-making and how to build a garment more, that type of thing.

At the same time, I never really studied it in terms of wanting to graduate with a degree in fashion. But I winded up moving into design at Ralph Lauren, and then I left Ralph Lauren for Calvin Klein and was head of design for all the menswear at Calvin, and it was a great opportunity for someone who didn’t really didn’t have that broad experience, honestly. I got thrown in and it was great. I did great, it was great, and we did a lot of great things. And then I went back to Ralph.

Let’s talk for a bit about that leap you made to Calvin Klein in 1990, where you launched the CK brand—and, most famously, created the boxer brief by slicing up a pair of long johns and putting them on Marky Mark, aka Mark Wahlberg, making him an international star. What was it like going through that kind of moment of success?

In terms of that ad campaign, while I was of course involved with it, there were a lot of people internally and externally who worked on putting together every aspect of that—including Mark Wahlberg. That came to us through David Geffen, who saw a pair of the boxer briefs in a meeting and said, “This is unbelievable. You need to put it on Marky Mark.” I was like, “Really?” And then it turned out to be the biggest thing ever. The business went through the roof.

And I learned a lot. I learned a lot about branding and marketing and connecting with people out there at both companies, because they both do a great job at that. I really had the best education. I call my time at Ralph Lauren “Polo University” because I feel like I learned so much there, even in my first month. It was such a different place, back then, and there’ll probably never be another company like it.

But it was also a different place for a different time. The world is different today—everything’s instant. Ralph wouldn’t be successful today the same way he was back then, because the competitive landscape and how fashion exists in the market today is completely different than when he started in 1967.

READ PART TWO OF OUR INTERVIEW

John Varvatos on His Search for the Rebels of Today—and the Music Icons of Tomorrow