Birthed against the 1970’s backdrop of increasing urban decay and resultant "white flight" into the suburbs, the landmark 1975 George Eastman Museum exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” elevated banal, overlooked, and unnatural vistas to the realm of fine art—and not everyone was happy about it. The 10 artists featured in the show were united by what the curator William Jenkins termed “stylistic anonymity,” a decidedly unemotional take on landscape photography that flew in the face of the more emotional approach established by Ansel Adams and his contemporaries.

The young photographers in Jenkins’s show—many of whom are now among our most celebrated shutterbugs—utilized stripped-down aesthetics and old-school view cameras to make pictures seemingly unfettered by claims of artistic artifice, favoring instead a more “objective” accounting of the 20th century’s man-made terrains (or “topographies”). Below, we’ve excerpted an essay on the group from Phaidon’sArt in Time, a collection of 150 entries tracing the development and history of artistic movements and styles, to expand on the movement and style, which is still exceedingly influential today.

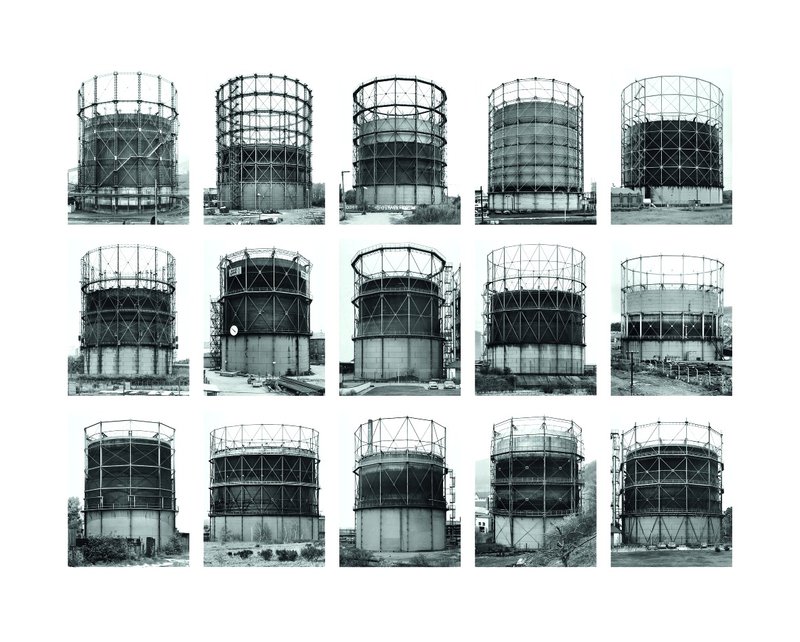

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Gas Tanks, 2009

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Gas Tanks, 2009

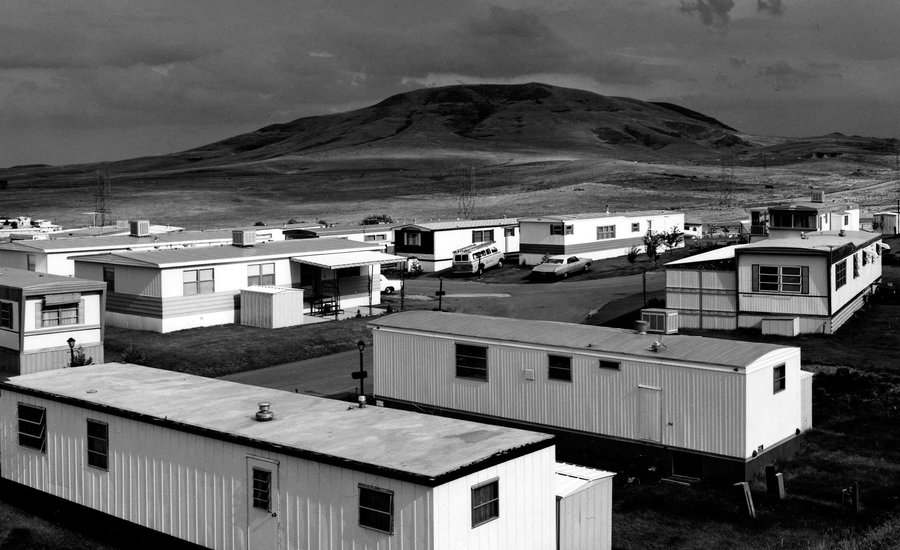

The New Topographics take their name from an exhibition titled “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape,” mounted in 1975 by William Jenkins, then curator at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. The show featured works by ten photographers: Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel, Jr. The photographs were all images of non-idealized landscapes, a mundane American vernacular—sprawling repetitive suburban areas, anonymous “strip” malls, one and two-story structures along highways, liminal urban areas—each bearing witness to a potential social critique.

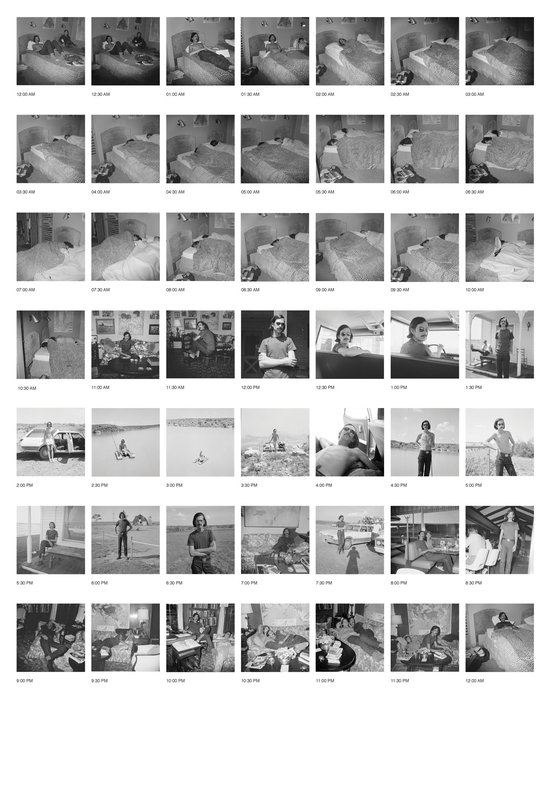

Bernd and Hilla Becher were the only photographers in the group to illustrate nineteenth-century subjects; instead, the husband and wife team, credited with the founding of the Düsseldorf school, documented nineteenth-century industrial decay. The Bechers worked exclusively in black and white, as did all the other photographers in the exhibition, with the exception of Stephen Shore.

The term New Topographics came to refer both to these photographers and to their work: a photographic anti-aesthetic that embraced an unflinching, nonromantic view of the ubiquitously marked American landscape, a human landscape that was so unobserved as to be taken for granted—the opposite of the Romantic sublime Western landscape of the nineteenth century, or its twentieth-century photographic counterpart that can be seen in the work of Ansel Adams and Group f/64.

In Stephen Shore’s U.S. 1, Arundel, Maine, July 17, 1974, color pairings hold the image together: the red in the Pepsi sign resonates with the red in the “99 cent” hamburger sign. The picture shows not Winslow Homer’s rocky shores or Andrew Wyeth’s golden fields, but the random and blunt effect of humans on the landscape, dependent on such conveniences as long-distance communication systems and fast food. From the perspective of the twenty-first century, the abandoned telephone booth—a curious private–public room—in the middle ground of the photo is peculiarly resonant.

In South Wall, Mazda Motors, 2121 East Main Street, Irvine, Lewis Baltz photographed the screen window facade of a modern single-story commercial building in southern California, in the glass of which is reflected a bromidic landscape of telephone poles towering over spindly trees, a parking area empty but for two cars, and a distant hazy horizon. A band of recently mowed grass next to a modest rock garden defines the photograph’s foreground, complemented by the passage of light grey sky in the upper register. The banal picture may be seen as a counterpoint to dramatic, romantic California landscapes uninterrupted by human incident, or to early twentieth-century pictorialist images by Photo-Secessionist photographers.

[related-works-module]