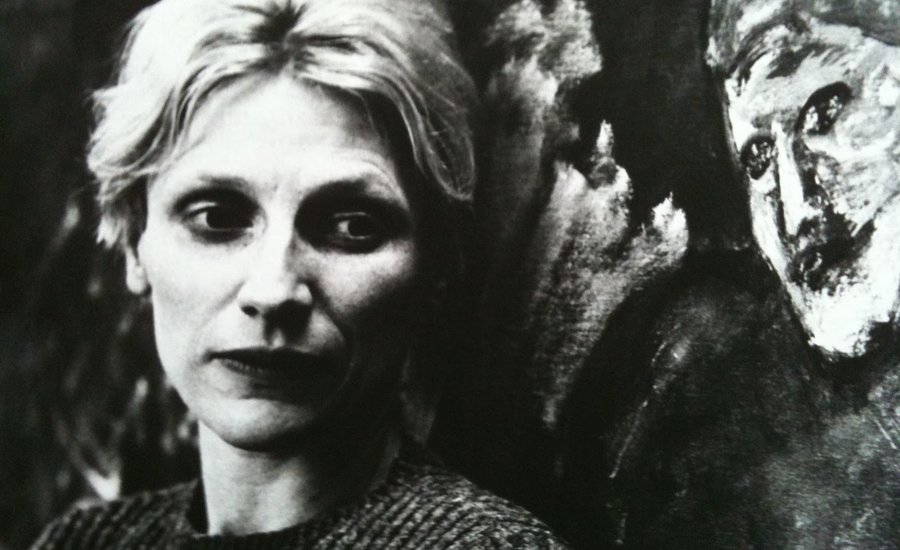

Before her untimely death in 2009, Nancy Spero combined drawings, selections of text, and repurposed imagery to create an impressive body of work that was both gracefully poetic and fiercely political. Whether through grand-scale scrolls or sprawling installations, Spero’s work often dealt with psychological trauma, the ugliness of war, and the problematic representations of women throughout history. She was also involved in many political protests and action groups during her lifetime, including co-founding the highly influential feminist art space A.I.R. Gallery.

Galerie Lelong in New York has currently devoted their space the first US presentation of Spero’s remarkable sculpture Maypole: Take No Prisoners . Made for the 52nd Biennale di Venezia in response to the Iraq War, Maypole presents similar motifs from her earlier body of work The War Series. By doing so, Spero wanted to show how history was once again repeating itself, with war being used as a tool for oppression.

In this excerpt from Phaidon ’s 1996 monograph Nancy Spero , Spero sat down with writer and curator Jo Anna Isaak to discuss her wide-ranging oeuvre as slides of the artist’s work were projected alongside them. The two speak about using art as a "vehicle for anger," the artist's obsession with the writings of Antonin Artaud, and and founding the first women-only gallery in New York City.

...

Isaak: This whole series, the scenes from the Mediterranean, the Lovers, Mother and Child paintings, all the Black Paintings, seem to be a happy period. Was the time you spent in Paris a good time?

Spero: Yeah, we were there from ’59 to ’64, although there was a brief interruption in 1960 with the Fuck You series of works on paper, which were very angry. I have these strange creatures, saying ‘ merde ’ and ‘fuck you.’ These worm-like or snake-like figures are a precursor of the War Series ; they are screaming and their tongues are sticking out.

Just like Caliban, the first thing you do when you start to speak is to curse. It is an appropriate response to being forced to speak in a language not your own. But also I was thinking lately that you are not such an angry young woman anymore (laughter).

Yes, I shifted and I changed. I think that the anger in the War Series and the Artaud Paintings came from feeling that I didn’t have a voice, an arena in which to conduct a dialogue; that I didn’t have an identity. I felt like a non-artist, a non-person. I was furious, furious that my voice as an artist wasn’t recognized. That is what Artaud is all about. That’s exactly why I chose to use Artaud’s writings, because he screams and yells and rants and raves about his tongue being cut off, castrated. He has no voice, he’s silenced in a bourgeois society. Then, we when came back from Paris, I really reacted to the Vietnam War and to the media coverage of it. I wanted to do something immediately, I was so enraged. Coming back from Europe, I was shocked that our country—which had this wonderful idea of democracy—was doing this terrible thing in Vietnam. I wanted to make images to express the obscenity of war.

This is the motive for the sexual, scatological series of bombs.

Yes, exactly, and all this craziness in ’66. The Sperm Bomb has to do with male power but the image is rather elegant. I think it resembles testicles.

Nancy Spero,

Sperm Bomb

, 1966

Nancy Spero,

Sperm Bomb

, 1966

It does. There is the whole sexual metaphor underlying war, so why not reveal it?

Most relevant to the Vietnam War was the helicopter. So I started thinking about the Vietnamese peasants, what they would think about when they saw a helicopter and how to visualize this.

This Helicopter and Victims, 1967 looks like a kind of prehistoric dinosaur figure.

There are bloody bodies, sculls, and remains. The helicopter is eating and shitting people, just like an efficient war machine. Now this is S.U.P.E.R.P.A.C.I.F.I.C.A.T.I.O.N. This is what I consider the obscenity of the war. I thought the terminology and slogans like ‘pacification’ coming out of the Pentagon were really an obscene use of language. They would firebomb whole villages and then the peasants would be relocated into refugee camps. This was called ‘Pacification and Re-education.’ So in this image the helicopter has breasts hanging down and people are hanging on with their teeth, like in a circus act.

I see, sucking on the tit of the Great American War Machine.

Yes, exactly. Now this is Crematorium, Chimney and Victims . These creatures are the victims coming around and licking the chimney. I think this has to do with the idea of the oppressor and the victim and the terrible symbiosis of that relationship. This was pre-feminist. Now this is Eagle, Victim and Medusa Head ; it is slightly larger. At this point I was using Sekishu, a Japanese handmade rice paper. It is very strong and fragile at the same time. I couldn’t work on it the way I did the others. So this is when I really started collaging, in the late 1960s, for the War Series . I print a lot of images on it now and collage them into the Bodleian paper. The doubled-headed eagle is a man’s head with a tongue and then an eagle’s head. There are dismembered bloody victims below.

Dismemberment is another motif that keeps coming up in your work. Your next work was the Artaud Paintings; how did you first become interested in Artaud? Were you reading him in French or English?

A friend of ours, Jack Hirschman at Indiana University, did an anthology of Artaud’s writings in translation. He became an Artaud freak. He was tall and dark and he became even more gaunt and more Artuad-like as he worked on the book. He got these other American poets in Paris to do translations of Artaud. They were brilliant, and so the first year of the Artaud Paintings, I used English. Then I decided that, as beautifully done as it was, it wasn’t right, that the original French was right. I went to Artaud because I wanted a vehicle to show my anger and he was the angriest poet there was.

I can’t think of a woman writer at that time expressing so much anger, yet it is interesting that Artaud so often speaks in a woman’s voice, he even invents imaginary daughters in order to express a woman’s pain, or the marginalized, all those outside of language. Julia Kristeva describes Artaud’s writing as an ‘underwater, undermaterial dive where the black, mortal violence of “the feminine” is simultaneously exalted and stigmatized.’ She says that if a solution exists to what we call today ‘the feminine problematic’, ‘it must pass over this ground.’ Freedom of speech, freedom of movement, freedom of the spirit involve coming to grips with one’s body by going through language, going through ‘an infinite, repeated, multipliable dissolution, until you recover possibilities of symbolic restoration: having a position that allows your voice to be heard in real social matters—but a voice fragmented by increasing, infinitizing breaks.’ I think this is a good description of Artaud’s writing as well as the trajectory of your development.

In 1969, in the first series of the paintings, I wrote a letter to Artaud in blood red ink, ‘Artaud I couldn’t have borne to know you alive your despair—Spero'. In this work, Pederastically in the Beginning… , I am quoting Artaud, ‘In the beginning, Father, Son and Holy Ghost. That’s a family, father, mother, and Baby Wee…I say grotesquely.’ He was very hateful about the family. In between his description of the family I collaged my images: there on top are the pederasts; Mother and Baby Wee are in the middle. The mother is very ferocious, like the fierce protective mothers in the Black Paintings. Artaud was mentally and physically ill but so brilliant. He lashed out at everything; that it is just what appealed to me.

The next work is called But the sleeper that I am…

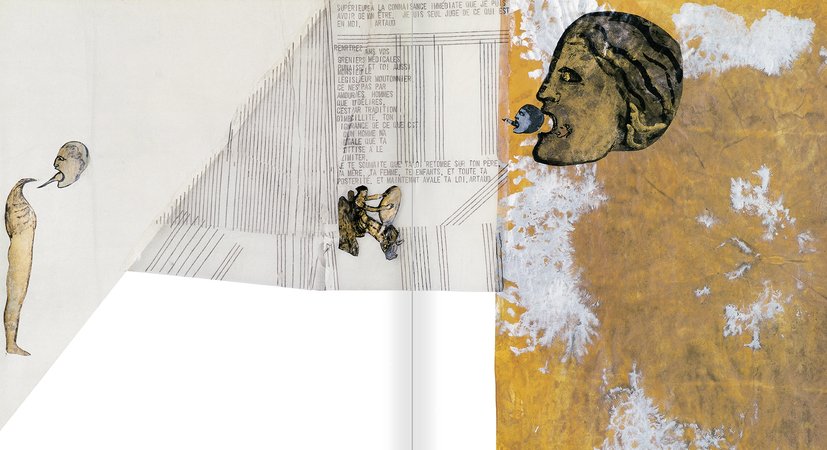

‘But the sleeper that I am will not fail to awaken and I believe this may be very soon,’ and then the nonsense words begin where he is speaking in tongues. He did that a lot in his writing. The first Codex Artaud was made in 1971, after two years of the Artaud Paintings. After the Artaud Paintings, I wanted to move into space, so I used these archival art papers that were around the studio and glued them together. They are all different types of paper. The first and the fourth piece are the same, the second is French vellum, a tracing paper.

Nancy Spero,

Codex Artaud I (detail)

, 1971

Nancy Spero,

Codex Artaud I (detail)

, 1971

Is the vellum colored silver and orange?

That is the painting. It is like a Rorschach blot, by that I mean I painted the paper and then folded it in two. The typing is on vellum and all those figures are collaged onto it. The left is a mummified figure, one of those strange Egyptian figures, and I added the tongue sticking out. Then there are some Greek classical figures, and then in the last the quotes are about ‘before I commit suicide.’ It is very ambiguous: ‘I want to know if there is another form of being.’ I guess he wants to know if there is an afterlife or if a spirit exists after his death…

In Codex Artaud III there is a figure holding a banner with a head on it…

The whole thing is about gesture. This image is heraldic, holding a shield up proudly. Those arms come from the poses of Roman bronze statues in Pompeii. The other one is holding a sign like the Chinese had for victims who are going to be executed or tortured with the crimes they have committed hanging from their necks. I got everything from any old source. But it all relates to death. In the War Series I have a female figure with four breasts leaning over and a nursing child. I was thinking of Romulus and Remus and the Egyptian goddess. In Codex Artaud VI the figure has four breasts and a penis. Now this turned out to be androgynous because I was responding to the ambiguity of Artaud’s sexuality.

What is going on in the patterned type?

That is what I call the Artaud rug. I just used Artaud’s name and I repeated it in certain ways. There was a lot of pattern painting going on at the time, pattern painting and Op art…

When he talks about the obscene phallic weight of the praying tongue, do you think he is talking about religion or language in general?

I thought it was about language, sex and religion. Another thing that enters into the Artaud work. There is a quotation in one of the last pages in his notebook on pain. I was suffering a great deal from arthritis, and I thought, that is what he talks about, mental and physical pain, I can use this.

What made you move away from the mythopoeic recording of unrightable wrongs that you were engaged with in the Codex Artaud to recording real case histories of torture?

In ’72 I had had enough of Artaud. I thought there is real pain and real torture going on, never mind Artaud. His pain is real, but it is the expression of an internal state. So this was an important step, to disengage myself from Artaud and to externalize this anger. I decided to address the issue I was actively involved in—women’s issues. I wanted to investigate the more palpable realities of torture and pain. The change had to do with my activities within the women’s movement and more immediate concerns in my own life. I had been going to AWC (Art Workers Coalition) meetings. AWC staged all kind of protests. The men were very outspoken in their complaints, but the women artists were getting an even rawer deal. I felt, you know, I had three kids at home still. Then I heard of something that really rang a bell: WAR (Women Artists in Revolution). WAR was a radical group of women artists who split off from the AWC to address the concerns of women artists. It was a very lively time, we wrote manifestoes and engaged in actions and protests. Once we went over to the Museum of Modern Art, eight of us, one woman even had a child of about six or so, dragging along. We marched into the office of John Hightower [then Director] and we demanded parity for women artists. He asked us to sit down and we wouldn’t sit down. We demanded parity and then we left. Later, I joined the Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists. We did all kind of actions, sit-ins and picketing. A whole bunch of us invaded an opening at the Whitney. We went inside and sat down, plop, right in the middle of the museum. It was good fun. I was really restless at the time, so angry and frustrated with my career. Then Barara Zucker got the idea that we could form a gallery. There were so many unaffiliated strong women artists floating around. Six of us met: Barbara Zucker, Dotty Attie, Susan Williams, Mary Grigoriadis and Maude Boltz. We discussed the idea of an all women’s gallery. We all thought it was a great idea. [AIR, the first women’s Gallery in New York City, opened in September 1972 with a group show of its founding members.]

The next large work is The Hours of the Night.

The title is Egyptian and refers to the passage of the Sun God into the underworld for twelve hours, but I made it eleven hours. This had to do with the terrors of the night and the war. I put all kinds of stuff I’d used previously, really cannibalizing my own work. ‘Body Count’ was printed directly on the paper, as way ‘The Hours of The Night.’ All the rest are collaged inserts. So that is 1974, when I was doing all sorts of crazy things with language and text—experimenting.

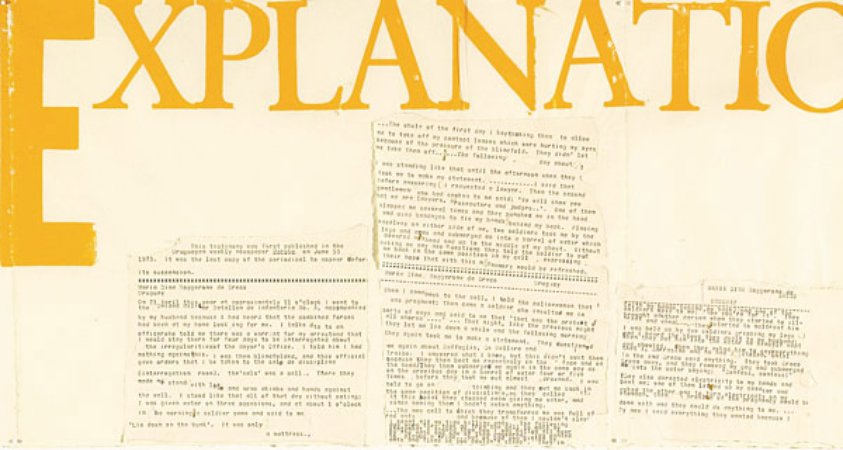

Nancy Spero,

Torture of Women (panel I)

, 1976

Nancy Spero,

Torture of Women (panel I)

, 1976

Is the panel that begins with the huge yellow letters ‘Explicit Explanation’ the first panel of Torture of Women ?

Yes it is. This is an explicit explanation of hell, the real hell of these women’s lives. Now on panel nine I started printing figures, not just letter. This was the first printed figure I used. When I was buying all these alphabets, the guy said to me ‘If ever you want to make a drawing, I can make you a plate and you can print it.’ That was the beginning…

Ah, so this is the beginning of your alphabet of women, your fundamental female lexicon.

Absolutely. So I printed her over and over inside this grid. Her hands and feet are cut off, she is really cramped; it is like a metaphor for women in jail cells, in prison. Actually, I make these prints from metal plates, and I inked up some dowel sticks and made those lines. The metal plates are for paper only. Now, when I print directly on the wall, I use polymer plates because they are flexible. My next work, Notes in Time on Women , took three years to do—1976 to 1979. If we include Torture of Women , which was originally planned as part one of Notes , then it took five years, but the information gathering had begun long before that. It was like working on a book, a solitary activity. I had to sequester myself. Rarely was anybody interested enough to ask to see my work in those days and I had nothing to show for years. I was stockpiling images and quotations, handprinting them and collaging them directly on the paper. Then, in the last few months of work, I put everything together.

Your account of the process reminds me of Wyndham Lewis’ description of how James Joyce made Ulysses : ‘He collected the last stagnant pumpings of Victoria Anglo-Irish life…for fifteen years or more—then when he was ripe, as it were, he discharged it, in a dense mass, to his eternal glory. That was Ulysses .’ Perhaps this is the stuff modern epics are made of. The stories are not taken from the front page of the newspaper. What you document in the panels on contemporary history are just incidents in the lives of ordinary women. For example, there is the story of a young woman medical student, top of her class, who was denied readmittance to medical school in her final year because she was Jewish, female, and as her reported noted, ‘had a much higher I.Q. than her male colleagues.’ Her case, filed in 1972, dragged through the courts for five years, like a suite in Chancery. You begin with a dance: ancient, mythological and contemporary images of women running in celebration. The celebration seems to be about the freedom of movement, the ability to dance, to leap athletically, unfettered.

The women are all dancing after a panel with the words ‘Certainly childbirth is our mortality, we who are women, for it is our battle.’ The passage is from an ancient Aztec book. It could be read as, ‘Certainly childbirth is our im mortality,’ as well; both are true. Artemis interrupts this celebratory dance, her fist raised. She is Artemis/Apollousa, the destroyer, the goddess of childbirth. Artemis, ‘who heals women’s pain,’ is a frequent figure in my work. So I have these figures running by. It is the same pose but the ink is unevenly applied, the handprinting varies, the different colors and pressures of the ink give the effect of multitudes in motion. Working on this piece was depressing; the history of women was so horrific, so negative, so oppressive, that I thought, how can I counteract this? That is how all these depictions of athletic women got started. Gathering all this information about women, being madder than hell, realizing further my status as a woman, I decided to make Woman the protagonist, to depict her as liberated, even if I know this isn’t really the case.

That makes sense, an image of agency, an image of physical autonomy that could stand up against the weight of these accounts that spoke only of women’s victimage. Throughout the text, women—ancient, mythological, modern—run, leap, dance, do somersaults, splits, cartwheels, anything they can to break up the ‘heavy phallic weight’ of the language.

Once you and I were talking about the printing process I use in which the same figure appears and reappears in an extended narrative format. You mentioned Gertrude Stein’s use of repetition and her term, the ‘continuous present.’ That is a good term for what I’m doing. The history of women I envision is neither linear nor sequential. I try, in everything I do—from using the ancient texts, to the mythological goddesses, to H.D.’s poems on Helen of Egypt —to show that it all has reverberations for us today.

[related-works-module]

RELATED ARTICLES:

Art Is A Weapson: Hans Haacke on How Art Survived the Bush Administration

Theaster Gates: Using the Art Economy to Funnel Funds to Underserved Communities